Just before the end of 2018, a pair of news items about fraud involving ads on mobile platforms got a lot of attention. One of the stories focused on Cheetah Mobile and Kika Tech, two of the biggest developers on Google’s Play Market app store. Their most popular apps (CM File Manager and Kika Keyboard), which consumers had (between the two of them) installed more than 150 million times, were removed from the official Play Market by Google, allegedly over reports about clickfraud. Soon afterwards, Business Insider published a report that, during 2018, mobile in-app advertising fraud had surged as much as 800% over the previous year.

These reports echoed (and continue to support) the results of research undertaken by SophosLabs, in collaboration with Protected Media, that found that advertising fraud in mobile apps is growing increasingly sophisticated and common, even in apps from established developers with a large install base.

Apps that engage in advertising fraud incur a significant cost on the end user unlucky enough to install one — both financial and personal. Not only do apps that engage in this behavior run down device batteries and use up the owners’ data plans, but the apps themselves may collect sensitive, personal data about the device, the owner, and the owner’s habits, and transfer that data to third parties who may have murky or nonexistent data privacy policies or very consumer-unfriendly privacy practices.

There are also societal costs to this type of fraud. In addition to providing a substandard experience to app users, the organizations that engage in ad fraud are paid by advertisers who expect to benefit from people being able to view their ads. By deliberately creating fake ad views, ad clicks, or app installation records, this drives up the price advertisers must pay, which increases the cost of the advertised products and services; Eventually those costs are passed on to consumers in price increases across the board.

Today, sophisticated ad fraud poses extreme challenges to the information security industry. Because these fraudulent activities take place “behind the scenes,” in undisclosed features within apps and over the mobile networks they use, it’s much more difficult for analysts to identify and detect apps that engage in these behaviors. But the news isn’t all bad: As bad actors continue to develop these insidious, secretive frauds, stakeholders and legislators are starting to take ad fraud threats more seriously, though they appear to fall into a legal grey area.

How do apps engage in advertising fraud?

Online advertising is a huge business, with billions of dollars per year circulating just to ensure that a picture of a product or service ends up in front of the eyeballs of the person most likely to want to spend money on that product or service. With that much money in play, it’s no wonder that criminals have latched on to this as a revenue stream.

Advertisers usually pay to display an ad (also known as an impression), with the ad networks (or their affiliates) charging the advertiser a premium if the user clicks through the ad to the advertiser’s website, and even more if the user completes a purchase as a result of the ad being displayed. The system requires an honest assessment of ad display and user behavior, and it falls apart if the advertisers and ad networks cannot trust one another to report truthfully.

In practice, the most common fraudulent ad behaviors fall into three broad categories: Unviewable ads, in which the advertisement is loaded, but never displayed to the end user; Bad traffic, in which ads are shifted through a network of redirects and iframes to display them in locations or on websites that are undesirable or not beneficial to the advertiser; and synthetic audiences, in which sophisticated, bot-like behavior simulates a user’s interaction with a displayed advertisement.

Unviewable ads render the ad invisible within the app, even though the app or vendor reports the impression, and may conceal where the ads are displayed. Apps that engage in ad fraud may use any of several different techniques to accomplish this:

- Display an ad in a 1×1 pixel WebView (a browser window embedded within an app).

- Display the ads outside of the viewport area, where nobody could possibly see them.

- Display (multiple) re-sized ads for the same thing.

- Display several ads in an iframe, loaded to a single ad slot, meaning that out of all the ads loaded, only one will actually be visible to the user.

Bad traffic deprives the advertiser of the work that goes into carefully selecting an ad network that can target a relevant audience and content that coincides with the advertiser’s brand. Targeting an ad to specific, relevant audience costs a lot more.

In this type of fraud, ad impressions are served on fraudulent websites (or within apps) where neither the audience nor the content is relevant to the advertiser’s brand, for example, an ad displayed on high traffic websites that serve illegal content (which are, traditionally, hard to monetize). By using a system of complex redirects and nesting ads within other pages, the app “launders” the ad calls so that the advertiser sees legitimate sites instead of the actual, fraudulent sites where the ads are displayed.

Synthetic audiences are a method in which automation or “mechanical turk” methods mimic or imitate legitimate audience interaction with an ad. It typically involves a combination of methods like bots, malware, and click-farms or app-install farms. The goal is to build a large “audience” of nonexistent “users,” and, consequently, feed on the online advertising ecosystem.

Click bots are one form of synthetic audience fraud, designed to perform fake in-app actions. The bots are designed to interface with the app internals and generate a sequence of in-app and on-device events that, in essence, produce the illusion that a large number of real users interacted with or clicked ads; In reality, the ads never reach carbon-based life forms.

Click-farms and app-install farms employ low-paid human workers, who physically click through ads or repeatedly install apps on devices, earning money for the fraudsters. The ads reach human eyes, but not truly engaged or interested ones, and are therefore not a valid target audience.

The following case studies in fraudulent and undesirable mobile app behavior illustrate the scope and nature of the issues facing both the advertising industry and the mobile app marketplace dominated by Apple and Google.

Case studies in fraudulent behavior

Case study 1: apps distributed outside of the Google Play Market

Snaptube is an alternative app for browsing or downloading YouTube content, developed by a company based on Shenzhen, China. The app has a global audience.

The first version of Snaptube was released around 2015, according to Sophos’ app database, which tracks new versions and updates of apps on the Play Market and elsewhere. Since Sophos began tracking this app, we’ve recorded more than 3,000 updates to the app, which means there have been about 2.5 new updates per day, every day, as long as we’ve been following it.

The app is only distributed via third-party app stores. One third party store reports that Snaptube has been downloaded over 660 million times. The Snaptube official website claims there are 300 million active daily users.

Google Trends data show Snaptube’s rising popularity over the past five years. From Protected Media’s research, the three countries where the most people use Snaptube are Morocco, Nicaragua, and El Salvador, but the app is widely used across South America.

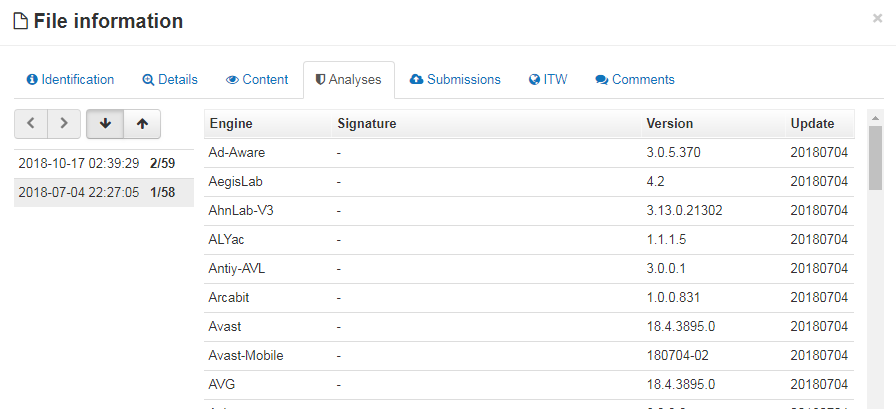

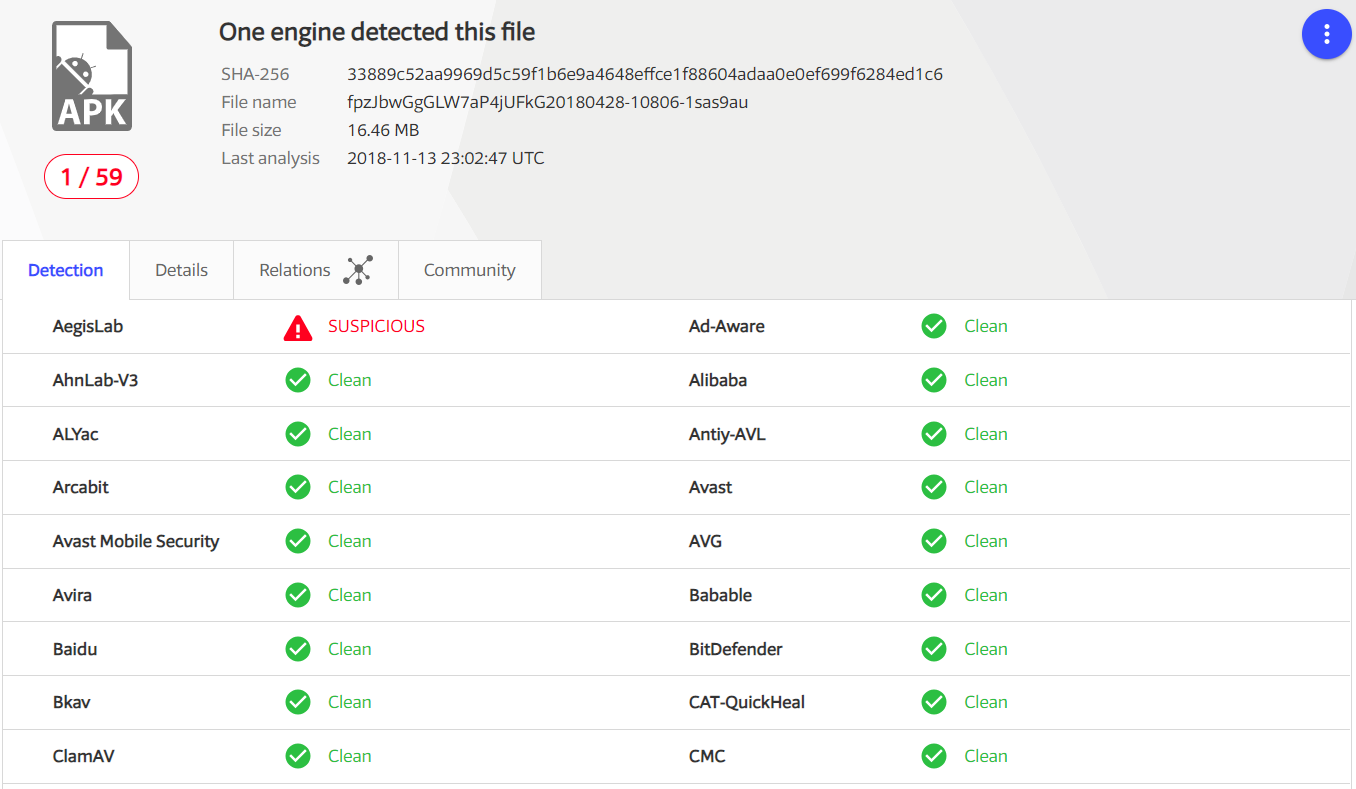

Among 3,000 samples, about 70% had fewer than 5 detections on VirusTotal, which means that few vendors have been paying attention to this app and its underlying behavior.

However, upon closer inspection, we discover that Snaptube engages in the following fraudulent advertising behaviour:

- Install fraud: it downloads additional advertised app payloads, and executes them on devices

- Invisible ads view: it creates invisible WebView underneath the app’s main window

- App masking: it generates a number of complex redirects and nested ad calls

- Affiliate marketing: it attempts to use JavaScript to perform fake in-app clicks

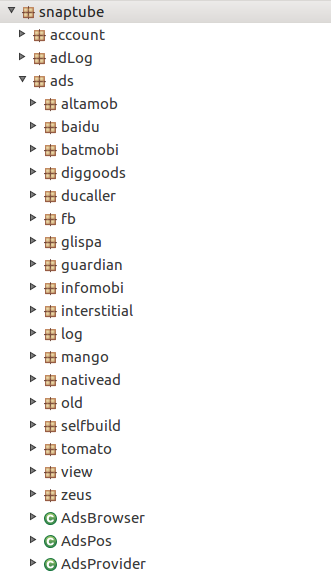

Snaptube contains a large number of ad displaying components from networks such as Altamob, Batmobi, Infomobi and Mango.

When running Snaptube in a device, it quickly generated more 200 network connections in fewer than 120 seconds, with no user interaction whatsoever. The network traffic shows the app downloads additional ad plugins, sends device info and personal info to remote websites, and generates sneaky redirects. What do we mean by “sneaky redirects?” They look like this:

GET /api/s2s/goto?id=5b182b9d319894102380bbe5&channel=online&provider=adspool&appkey=5b10cd2b6904967f148638a9&dsp=keepmobiCPA&plm=%24%24%24vas%24%24%24-snaptube&name=Ihmr%20Playwithme%2B%2FAU%2B%2FOptus&appid=com.snaptube.premium&dspid=%24%24%24vas%24%24%24&p=1499.4&rid=5b182b9d319894102380bbe5&tid=5b3da9cc43daac08b6bc0556&deviceid=f56a219d-fe1c-42f4-8ed6-d20f3c24880d&sid=fbab93e7-dc82-4ab5-b5c4-ad1786c77539&affiliate_id=5b10cd2b6904967f148638a9&mcc=505&oip=220.101.27.18&oipc=AU&status=run&vas=1 HTTP/1.1 Host: api.infomobi.me ... HTTP/1.1 302 Found Location: https://q-mobi.go2affise.com/click?pid=24&offer_id=706628&sub1=5b3da9cc43daac08b6bc0556&sub2=1..5b10cd2b6904967f148638a9 ... <p>Found. Redirecting to <a href="hxxps://q-mobi.go2affise.com/click?pid=24&offer_id=706628&sub1=5b3da9cc43daac08b6bc0556&sub2=1..5b10cd2b6904967f148638a9">https://q-mobi.go2affise.com/click?pid=24&offer_id=706628&sub1=5b3da9cc43daac08b6bc0556&sub2=1..5b10cd2b6904967f148638a9</a></p> ... <a href="hxxps://bk4p0ne.com/?id=33998&offer_id=116756&clickid=5b3da9cf2a567900016aace1&clickid2=24">Found</a>.

|

This traffic indicates the app used several redirects: The advertisement came from infomobi.me, was redirected throgh go2affise.com and finally landed on bk4p0ne.com. The bk4p0ne.com, which is less than a year old and privately registered, redirects users to multiple clusters, and shows them different ads. The two websites below are examples of traffic that originated with bk4p0ne.com. The first one comes from a porn site, while the second one sells lottery tickets:

Moreover, the key word keepmobiCPA (where CPA refers to “cost per acquisition,” or paying for people who install apps) in the traffic, and captured JavaScript code, reveal that Snaptube uses JavaScript to perform fake in-app clicks that simulate user interaction.

Case study 2: apps removed from Google Play Market

In 2018, Sophos discovered that Google had removed half a million apps from the Play Market. What’s unsual about that is that the newly-removed apps had been installed on 2 billion devices, in total. It is impossible to identify all the reasons that Google removed those half million apps from the Play Market, but it’s likely that at least some of them were removed due to suspected or alleged ad fraud. It’s also important to note that just because an app is removed from the Play Market, those apps may still reside on individual users’ devices.

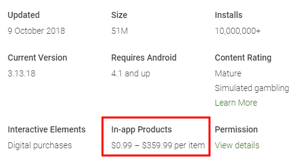

The popular CM File Manager and Kika Keyboard apps from Cheetah Mobile were among the apps removed from the market. Protected Media has kept track of the top 10 apps that are alleged to have engaged in ad fraud that disappeared from Google Play in 2018:

The first column is the internal package name of the apps. The endpoints column is a count of how many devices still have the apps, according to telemetry from Protected Media. The install number and date range are collected from Google Play, but apps may be distributed through third-party markets as well.

| Package Name | Endpoints | Installs | Date Range |

| com.jiubang.fastestflashlight | 762687 | 10,000,000+ | April 2016 – July 2018 |

| com.flashlight.brightestflashlightpro | 673414 | 10,000,000+ | August 2016 – July 2018 |

| com.gunbroker.android | 53820 | 500,000+ | February 2014 – March 2017 |

| com.survivalonraft2.sandbox | 49110 | 1,000+ | September 2018 |

| com.comikin.reader | 35648 | 500,000+ | February 2018 |

| com.ioob.appflix | 22578 | 500,000+ | January 2018 – August 2018 |

| air.lift | 21996 | 1,000,000+ | January 2017 – May 2018 |

| com.appini.digitalclock | 20351 | 100,000+ | December 2017 – June 2018 |

| com.f1.racing.championship.drivingsimulator | 18095 | 500,000+ | June 2018 – July 2018 |

| com.racing.police.crime.driver | 13808 | 500,000+ | November 2017 – June 2018 |

Some of these apps had been available on Play Market for more than 2 years, and attracted upwards of 10 million installs.

The developer of the first example, “com.jiubang.fastestflashlight,” (“Beacon Flashlight” in the app) is a company named GOMO; They claim to be the world’s leading mobile application developer (and mobile advertising platform), with more than 2 billion total downloads for all their apps. Their app lineup includes Faster Flashlight, GOMO Reading, GO Launcher, GO SMS, GO Keyboard Pro, S Photo Editor, GO Music, GO Speed, Z Camera, and Z Launcher.

On May 25, 2018, an independent researcher discovered unsecured GOMO backup data exposed on the web. The leaked data contains the complete backend system for many of GOMO’s products. The data, 28GB of compressed files, close to 100GB of uncompressed data, contained a treasure trove of information about its users.

One table contained about 50 million user account records, including email addresses, mobile phone numbers, passwords, language preferences, country, and other account related information. A second table in the account database contained device information such as IMEI number, IMSI number, phone model information, language, country, and the type of connection used by the devices. A third table contained internal purchases, games, promotions, messages, and contacts.

What’s worse, GOMO’s apps are very popular with children, so a lot of the leaked data includes details about millions of children. The GOMO leak may have violated the GDPR in Europe and the COPPA law protecting the privacy of children’s online data in the United States.

Most versions of the “com.jiubang.fastestflashlight” did not trigger detections by endpoint antivirus products, judging by Virustotal’s tepid reports.

When we tested this flashlight app in a real device, it shows a very clean interface with no ads, and no notifications, either inside or outside the app.

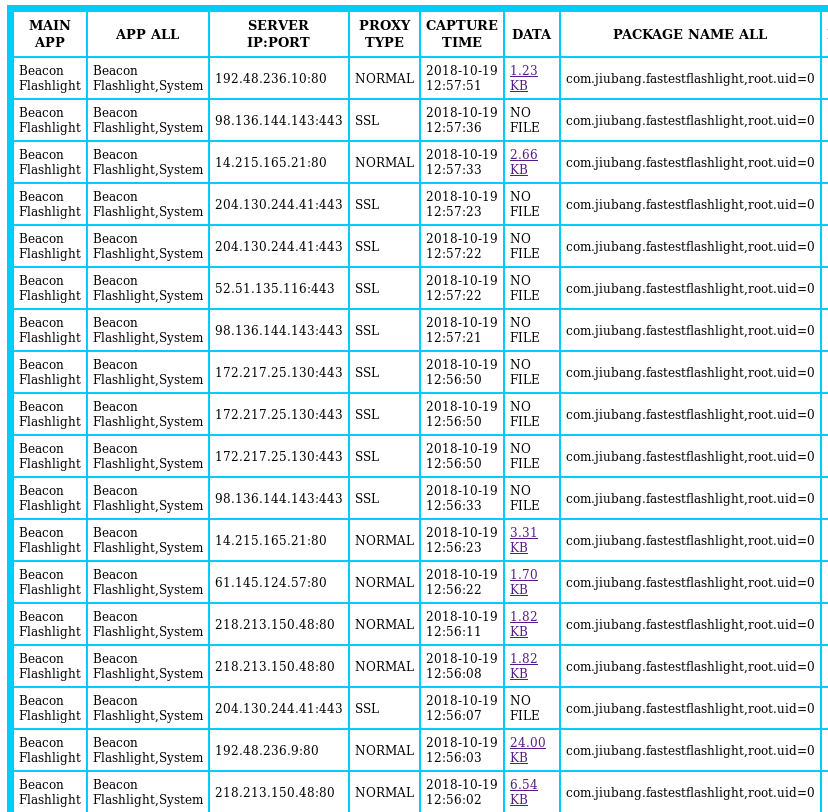

But a closer look at the network traffic generated by this app tells a different story. Using a platform SophosLabs developed to track network behavior of individual apps, the app generated about 100 unique network connections in the first minute that it was running.

A lot of them attempt to collect device and personal information. However, the traffic highlighted below is of particular interest because they reference important terms, such as:

- GDPR applies

- Ad domain

- Bid price, charge price

- Currency USD

- Publish company GOMO

- Bundle name

hxxp://ads.mopub.com/m/aclk?appid=&cid=b4e27f3c1f4f4df9be22660bab7a258e&city=Rozelle&ckv=2&country_code=AU&cppck=6D056¤t_consent_status=unknown&dev=Nexus 6&exclude_adgroups=404a78e35f5f4cb6a3bd576ed0dcebb7&gdpr_applies=0&id=39b2ed631e694b1a808b86093e5a51a2&is_mraid=1&mpx_clk=http://mpx.mopub.com/click?ad_domain=heartofvegasslots.com&adgroup_id=404a78e35f5f4cb6a3bd576ed0dcebb7&adunit_id=39b2ed631e694b1a808b86093e5a51a2&ads_creative_id=b4e27f3c1f4f4df9be22660bab7a258e&app_id=a0c9272de9514729a2bc060496d97518&app_name=beacon%20flashlight&auction_time=1539914241&bid_price=7.67&bidder_id=f67445oEOC&bidder_name=Aarki&campaign_id=c2f72ddba5634e63b1201df108753576&charge_price=5.57&asc_price=0&ck=1757F&ckenc=2&country=AUS&latlon=-33.837837837837839%2C151.19555545926337&creative_id=38329%3A84ade41b4aa725e83fd257de79bafa97& currency=USD&impression_id=d53504d4-8614-4b29-b2bc-548efe36e76f&latency=0.05&mopub_id=ifa%3Af56a219d-fe1c-42f4-8ed6-d20f3c24880d&paid=0&pub_id=de73ca5a7d8c42d6a4eec0ddc809b2e6&pub_name=GOMO%20limited&pub_rev0=7164155173307489&request_id=3d49b9c31db8427eb47a464e6ccb555f&seat_id=Aarki&units=0&adgroup_type=marketplace&adgroup_priority=11&gdpr_applies=0¤t_consent_status=unknown&bundle=com.jiubang.fastestflashlight&os=Android&osv=6.0.1&priority=11&req=3d49b9c31db8427eb47a464e6ccb555f&reqt=1539914241.0&rev=0&udid=ifa:f56a219d-fe1c-42f4-8ed6-d20f3c24880d&video_type= |

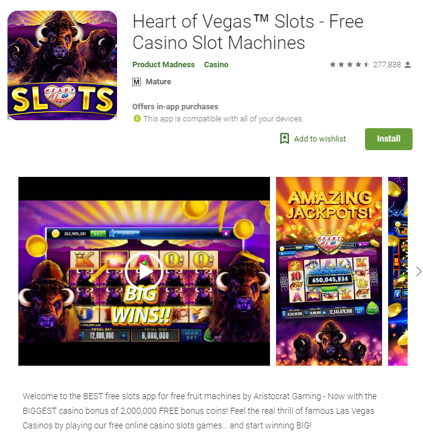

We believe this URL may be a paid link, which search engines like Google strictly forbid. Google asks users to report instances of people buying or selling links, and state they will penalize both the buyer and seller of links if they detect the practice. The link directed users to a casino game that is still available in the Play Market:

It’s worth noting that this app also reports having more than 10 million downloads, and discloses that it may charge up to $359.99 per item for in-app purchases. That’s a lot of cheddar for virtual coins in a simulated gambling app.

Case study 3: aggressive pop-ups when web surfing

Ad fraud is not a platform-specific problem: It is widespread on both the Android and iPhone ecosystem, and it takes many forms, including fake alerts and aggressive “contest winner” messages.

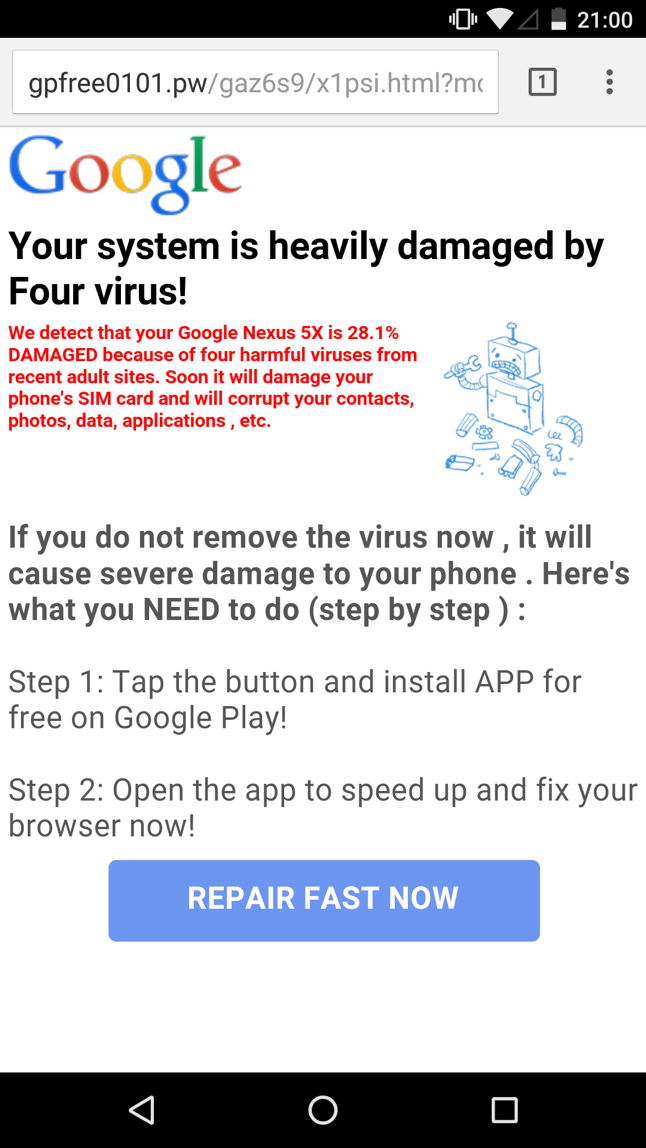

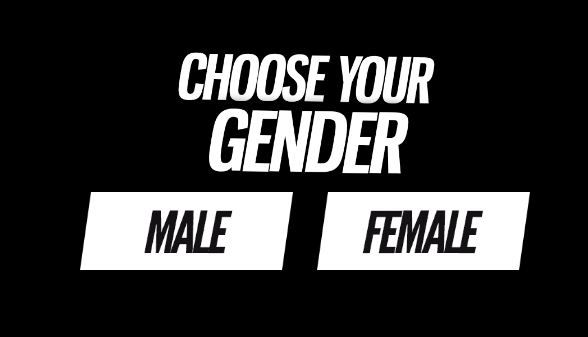

For example, while browsing an otherwise normal site, no matter which device you use, an ad call may pop open a new tab in the mobile browser, which redirects to pages that look like these:

This “warning” message uses a template that embeds specific information about your phone’s manufacturer and model into the page itself. The text in red contains the description “Google Nexus 5X” because that version of the phone was used to browse to the site. The User-Agent string transmitted by the phone’s browser sends that information to the website, which then throws it back in your face to lend the dire warning credibility. The warning is bogus.

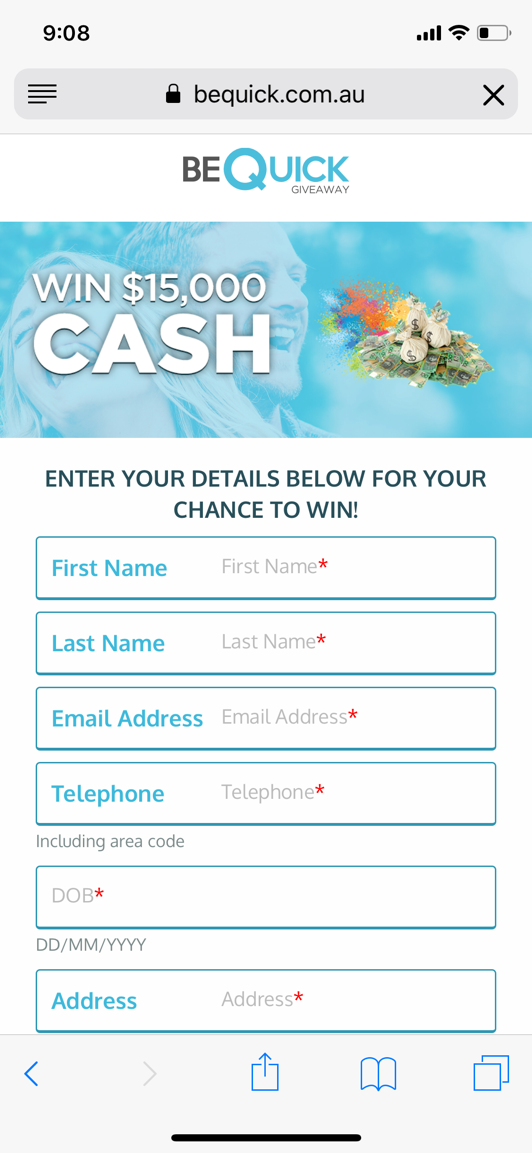

Now, consider this message telling the viewer that they could win a large cash prize.

These highly deceptive ads employ the use of multiple redirects, which prevents the user from returning to the original website. Scripts may prevent you from doing anything other than closing the tab or the entire browser.

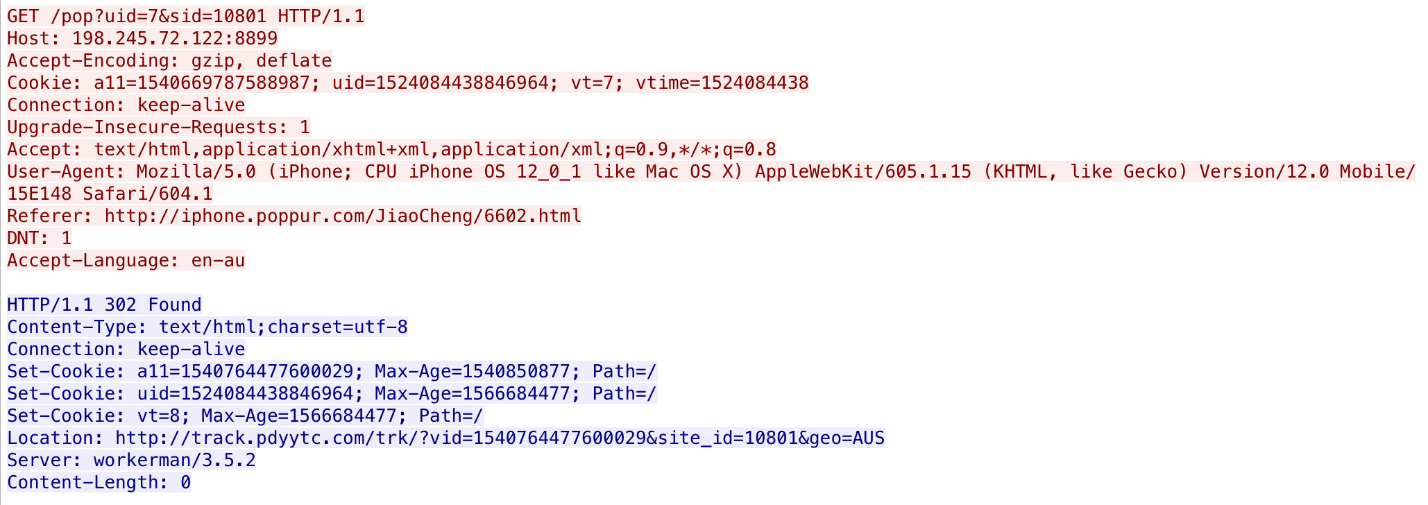

Looking at the network traffic generated when we visited the second site shown above, using Safari on iOS, we have basic information that tells an analyst where the site is hosted, how you got there, and in some cases, where you’ll end up next. In this case, it’s being hosted on a bare IP address, serving web content from a non-standard port:

- IP address: 198.245.72.122:8899

- User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; …)

- Referer: the originated website, hxxp://iphone.popur.com/JiaoCheng/6602.html

- “302” redirect to: hxxp://track.pdyytc.com/…

Case study 4: Google Play mobile in-app pop-ups & notifications

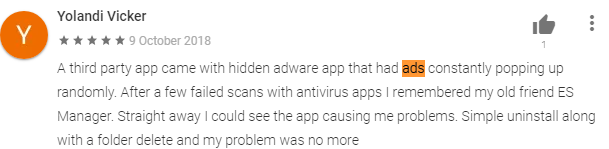

Many applications on Google’s Play Market skirt the edge of what one might consider malicious behavior, and are not really safe or pleasant to use. We’ve recently reported on networks of apps that engage in aggressive promotion of app downloads, almost to the point where one must question whether the main purpose of the app is to just promote other apps. Some apps show annoying full-screen ads or repeatedly display notifications in the notifications bar. These apps routinely engage in the kinds of deceptive and unfair practices that enrage many people.

- Constantly pop up ads

- Charge users a lot of money in order to remove all ads

- Even if you pay, you may still see a lot of ads

Here are some reviews and comments from users about some of the apps we looked at that engage in these practices:

Some apps exhibit ransomware-like behavior. They may:

- Change the lock screen

- Show notification everywhere (inside or outside apps)

- Every time open the app, there is an ad

- Frequently ask for payment

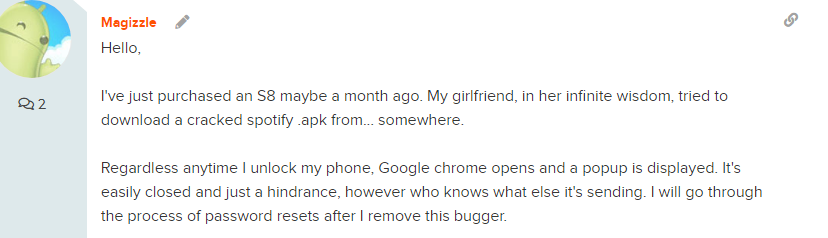

As a researcher, I heard there are some complains about pop-ups exiting sleep mode. I did some research, and here is the conversion between several end users. The user pointed out that the Z camera app (from GOMO) may cause the issue. Z camera is a photo editor and “Beauty Selfie” app on Google Play.

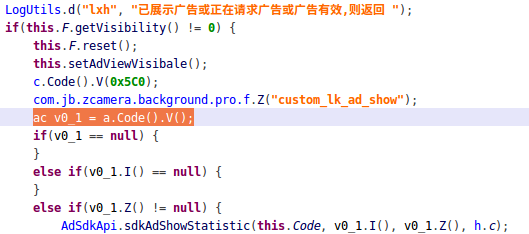

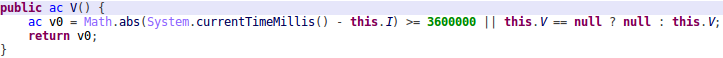

After digging the decompiled code, here is our finding:

- the app will cache ad sites once every hour

- The app uses the USER_PRESENT permission to launch a full screen ad when the user unlocks their device

Let us turn back to the first paragraph that mentioned the Cheetah Mobile app (CM File Manager) and Kika Tech app (Kika Keyboard), which were reportedly removed by Google due to the engagement in “clickfraud” by claiming credit for app installs. The report was firstly released by an app analytic firm Kochava, and it caused Cheetah’s stock price to drop 30% on Nov. 27, 2018.

According to Ryan Whitwam of Android Police, a mobile news website, the problem was endemic.

Credit for app installs is yet another advertising model – one that pushes apps. If you see an ad, you might end up clicking, downloading, and installing that app. Advertisers might pay up to $3 per install when they acquire a new user in this fashion, but claiming that bounty is tricky. When the app is opened for the first time, it does a “lookback” to see where the last click originated. The mobile analytics company Kochava claimed Cheetah and Kika were abusing this system using their apps.

In Cheetah’s “click injection” case, the app (a file manager) requires permission to view and open your installed apps, but Cheetah was alleged to watch for any new app installation and submit a fake click, even if they never served the ad to anyone. They also use their permissions to launch apps to ensure they get the bounty.

This affects the advertisers, of course, but legitimate developers could also lose out on a legitimately earned install bounty.

Cheetah attempted to blame third-party advertising SDKs or ad networks for this behavior. One of the SDKs can be found in Snaptube app – Batmobi.

Conclusion

In this joint paper, Sophos and Protected Media presented several ad fraud case studies – Snaptube, fastestflashlight, and Z Camera from GOMO, as well CM File Manager or Kika Keyboard.

Although the core products from these companies are different, they have same business model – advertising, just like Google and Facebook. Today, we are unavoidably living in the world of digital advertising. As Google says, “the digital advertising ecosystem is built on trust, working at its best when all participants are good, and when no one tries to deceive anyone else. That’s why ad fraud is potentially damaging – it can erode trust.”

In the end, everyone is a victim of ad fraud, especially the publishers and advertisers.

Publishers like Google or Facebook should publish more clearer and stricter policy and punish any violation. Companies like Cheetah, Kika Tech, and GOMO should carefully test 3rd party SDKs before adding them into their apps.

These companies should protect their customers rather than leave them to be victimized by ad fraud. Moreover, the entire security industry needs to be collaborative. We need to collaborate and cooperate with government, law enforcement, ad network operators, advertisers, and the users of mobile devices now, and in the future.

Acknowledgments

SophosLabs and threat researcher Rowland Yu gratefully acknowledges the collaboration on this research project with Protected Media and its CTO and cofounder, Dr. Zac Sadan. This research was first presented at the AVAR ’18 conference.

slowup

OR

detection engines grow the f-ck up and remove ALL malware apps on mobile: those displaying third party interweb ads, those loading third party analytics, those harvesting user information without INFORMED consent

Intellectual Honesty has become a rarity

menocal

Hi, Great article! Looking at an analytics dashboard, what patterns would I see that could tip off this kind of fraud?