Mathematics is a complex and esoteric field that underpins science and engineering, notably including the disciplines of cryptography and cybersecurity.

(There… we’ve added a mention of cybersecurity, thus justifying the rest of this article.)

The topic of mathematics has been extensively and fervently studied from at least ancient Babylonian times, and the names of many famous mathematicians have entered our everyday vocabulary, in phrases such as Pythagorean triangles (those that have a right angle in them), Cartesian geometry (working with shapes on flat surfaces), computer algorithms (instruction sequences that work iteratively or recursively to compute a result), and Penrose tilings.

Penrose tilings, if you’ve ever met them, were figured out by Sir Roger Penrose in the 1970s, and dealt with fascinating and unusual ways of covering surfaces in combinations of shapes.

In case you’re wondering why the word algorithm doesn’t have a capital letter like the others, that’s because it’s not a precise rendering of an original name, but a word derived from Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, an influential mathematician, geographer and astronomer who lived about 1200 years ago in an area to east of the Caspian Sea and south of the Aral Sea, a region now split between Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Tiling made funky

Tiled surfaces are commonly seen, for example in bathrooms, kitchens and walkways.

And on roofs, of course, but we’ll ignore roofing tiles in this article because they’re designed to overlap, so they keep rain out without needing to be individually sealed against one another.

Even carpeted areas are often tiled, especially in offices, so that parts of the floor can be re-tiled without ripping up and replacing the lightly used carpeting around the worn-out parts.

If you’ve ever visited Sophos HQ in the UK, for example you’ll know that it’s a largely open-plan area that is covered in square carpet tiles in various gentle shades of blue and light green:

As you can see, square tiles form what’s known as a periodic pattern, meaning that the pattern repeats itself every so often.

In the example above, the precise grid used in the layout ensures that the pattern repeats itself in both dimensions after moving just one square up, down, left or right.

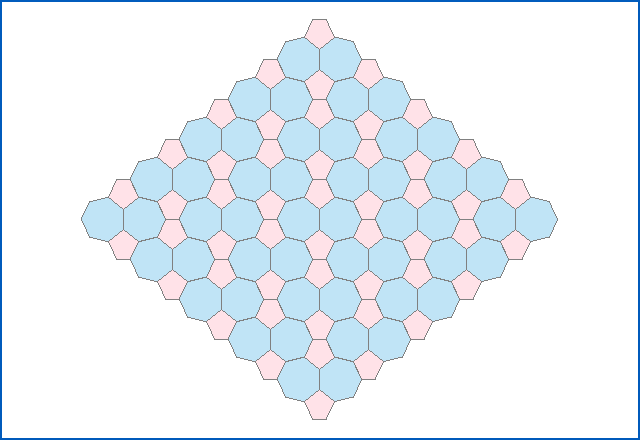

More complex and visually appealing patterns, which are nevertheless periodic tilings because they keep repeating, can be made with regular combinations of simple shapes, such as the hepta-pentagon:

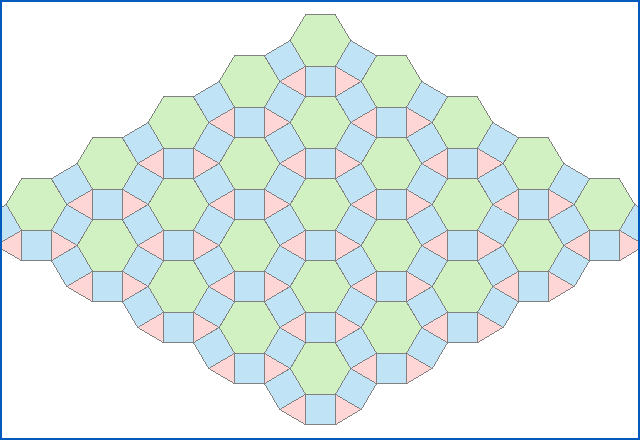

Or the rhombi-tri-hexagon:

Penrose tilings

That brings us to Penrose tilings.

Although Sir Roger Penrose is probably most famous as the winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2020, he is also renowned for his work into a special class of tile patterns known as known aperiodic tilings.

Unlike periodic tilings, which repeat every so often, aperiodic tilings never repeat, no matter how carefully you choose the next piece to place, and where to place it…

…even though the tilings are based on a finite number of shapes, and cover an infinite surface without any gaps or overlaps.

Periodic tilings are a bit like rational numbers (fractions based on one integer divided by another), in that eventually they repeat no matter what you do.

If you divide 22 by 7, for example, you get about 3.142.., usefully close to the value of Pi, which is about 3.14159…

But 22/7 actually comes out as 3.142857142857142857… and that pattern 142857 keeps repeating forever, because the number is the ratio (thus the description rational number) of two whole numbers.

In contrast, the true value of Pi is irrational: it can’t be reduced to a ratio, and its value in decimal never falls into a repeating pattern.

What about a similar sort of never-repeating sequence based not on numerical values but on shapes?

Would you need an infinite number of different shapes to guarantee a pattern that never repeated, or could you get your (admittedly never-ending) tiling job done with a finite set of tile shapes to choose from?

Penrose whittled down the number of different shapes needed to guarantee non-repeating tilings to just two, but the question has lingered ever since: Can you find a single shape, a single tile, that can be laid down repeatedly to cover an infinite surface without ever repeating?

In what passes as a mathematical pun, this Holy Grail of tiles is known as an einstein, which can loosely be translated as “one shape” in German, but also echoes the name Albert Einstein, of E=mc2 fame.

Introducing… the Hat

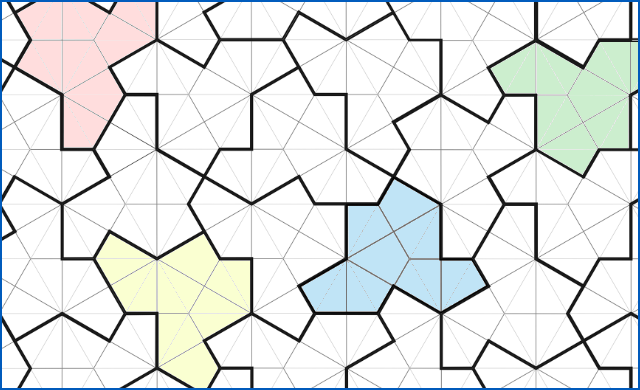

Well, a mathematical foursome spearheaded by a British shape-searcher called David Smith, claims that einsteins do exist, and have revealed a triskaidecagon (that’s a 13-sided figure) that they’ve dubbed the Hat.

They claim they’ve proved that the Hat generates the long-sought-after outcome of an aperiodic pattern, all on its own:

Simply put, if you tile your floor, or your porch, or your driveway, or even the local football pitch with a supply of Hat tiles…

…you’ll eventually cover the whole surface with a pattern than never actually repeats.

For all that it displays various “sub-designs” and apparent self-similarities as you construct your Hat-based artwork, this is the Pi of floor tiles: try as you will, you’ll never get a regular, periodic pattern out of it.

What to do?

We’re not going even to attempt a description of the proof here – in all honesty, we haven’t yet managed to digest it ourselves – so we shall merely suggest that you study it in your own time. (Perhaps set aside a long weekend for the task?)

But if you want to play with the concept of aperiodic tilings, why not bake yourself some Hat biscuits, or cookies if you’re from North America?

If you’ve got a 3D printer, you can download a design to make your very own Hat-shaped pastry cutter!

*Putting the hat of the GinderBread Instruments CSO*.

The GinderBread Instruments proudly present a 3D printed aperiodic tile cookie cutter. Based on the Smith, Myers, Kaplan, and Goodman-Strauss's aperiodic monotile.https://t.co/hEdtNCXX1d pic.twitter.com/FoyedYcDM9

— Nikolay Tumanov (@ntumanov_Xray) March 28, 2023

Anonymous

Quick German note: Stein means “Stone” so “einstein” means “one stone,” and the word ‘shape’ translates to “form” in German

Paul Ducklin

I don’t think the pun is meant to be entirely literal, more of a metaphor… like saying “single shingle” or “unislab” in English.

The paper itself uses the English term “monotile”, for which I think you will accept “einstein” is an acceptable punning equivalent…

Bastion

Imma gonna go out on a limb and suggest that they named it “one stone” because “stone” and “tile” are somewhat synonymous in certain contexts, as originally tiles were only made from stone (brick even really being a type of stone).

Paul Ducklin

That was certainly my assumption.

Given that we talk of “paving stones” even when they are cast or moulded into specific shapes…

Anonymous

“Stein” can indeed also be translated as “brick”

Ken Sims

I thought that the word algorithm was derived from the dance moves of a former US vice-president: an Al Gore Rhythm.

Paul Ducklin

Ouch.

As an aside, the word was apparently first brought into English as “algorism, presumably slightly closer to how the bearer of the name himself was inclined to say it, before settling in as “algorithm”, in that curious way that imported words and phrases have of finding their own form, like “plonk” (originally “blanc”) for table wine.

Tim Boddington

As I understand it, an important feature of the work is that flipped and non-flipped versions of the pattern are intermixed.

Paul Ducklin

IIRC the best aperiodic monotiles until now required special rules of use to make them work – either specific alignments that were not allowed (eg. no flips, only certain adjacency layouts allowed), or specific overlaps permitted (e.g you could file a roof but not a floor).

As far as I know, when you tile a surface you can stick down a new tile in any edge-to-edge adjacent position you like that doesn’t preclude further tiles being laid (e.g. by creating an inaccessible “corner”), and you can’t provoke a repeating pattern even if you wanted to.

Bastion

As for its nickname “the hat”, to me it looks more like “the shirt”, as in a v-neck t-shirt that is half tucked in… 😂

Paul Ducklin

Hat trips off the tongue a bit more readily than, say, Halftucked Vee-Tee.

Just saying.

Anonymous

Surely it is a boa constrictor which has just swallowed an elephant…

Anonymous

The researchers have now discovered a whole family of einstein shapes. “The hat” is just the start!

Paul Ducklin

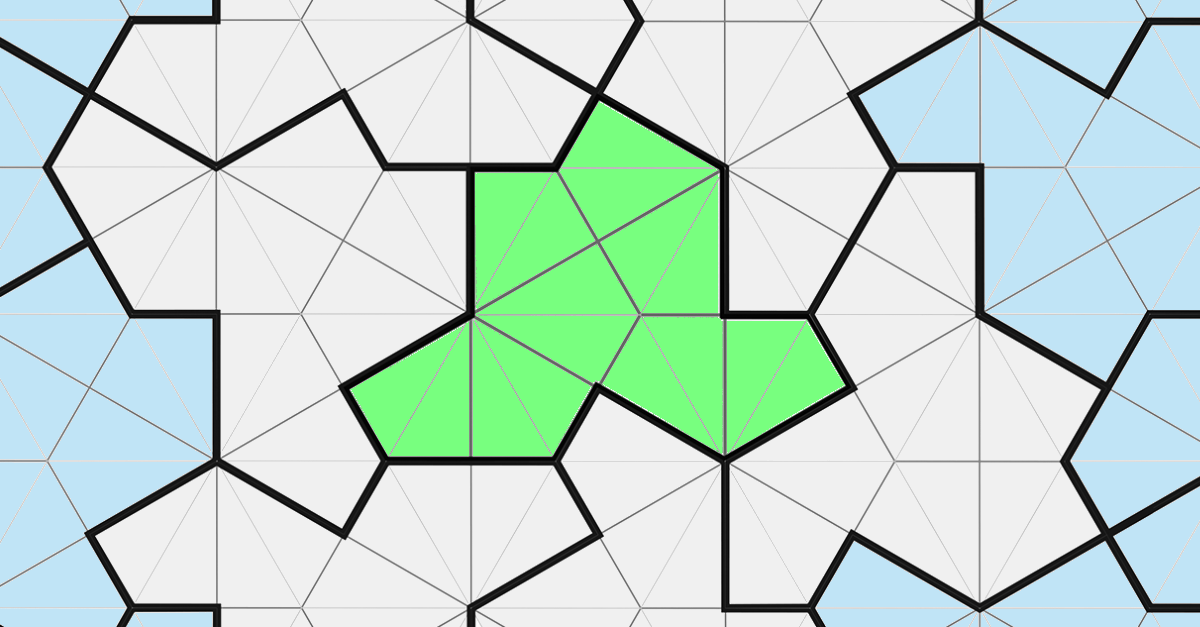

It also turns out that you can change the ratio between the long line segments and the short ones that make up the sides of the hat… and at only one ratio (where the two dimensions are equal), the tiles do fall into a repeating pattern but at all the other “slantednesses” they do not.

The paper authors have an animated video the shows a surface tiled by hats as their shape adjusts, and how the patterns (or non-patterns”) change too.

Chris

To what level are they saying it doesn’t repeat patterns. Because I see where it does repeat. Not the single tile, but the collection of tiles surrounding one tile is repeated through out.

Paul Ducklin

You’ll need a bigger image than the ones here to check visually for repeats!

There are only so many orientations (angle and flippage) that each tile on the surface can be in. So you will inevitably be able to slide one tile, or even a local group of tiles, across the tiled surface and find another group it lines up with exactly somewhere in the room, football field, planet, universe…

…but that doesn’t mean you have found a *periodic* tiling, where the repeats can be predicted algorithmically.

If you search for the digit sequence “14159265’ in the decimal representation of Pi, you will find it immediately after the decimal point and then infinitely often again, for as long as you care to keep looking. But these repeats will be down to chance, not to periodicity (meaning “in a predictable, ever-repeating pattern”).

Dan Bach

This was a nice article, a good comparison with digit sequences. But you got the most important thing wrong, and you put it in bold face: “Can you find a single shape, a single tile, that *can be laid down* repeatedly to cover an infinite surface without ever repeating?” This misses the point, because a domino would do what you state (line up all dominos vertically, but take a single pair and twist it 90°). The idea of this Hat shape (and the more recent Spectre tile) is that it can ONLY tile aperiodically, never periodically. This key idea has been misstated in several public articles, including a NYT headline (although the article got it right).

Paul Ducklin

That sentence may be somewhat imprecise (though this is not a mathematical treatise so I am not planning to change it)…

…I think that the earlier mention of “periodic patterns” seen in terms of “repeating” makes it clear what is meant, without introducing and using the word “aperiodic”, which is not a common word, at least to people for whom English is not their first language.

(And even then, its meaning is unclear – is aperiodic to periodic as amoral is to moral, which is quite different to the relationship between the words moral and immoral?).