Just yesterday, we wrote about a bug in Google Pixel phones, apparently now patched, with potentially dangerous consequences.

The bug finders, understandably excited (and concerned) by what they’d found, decided to follow the BWAIN principle for maximum, turning it into a Bug With An Impressive Name: aCropalypse.

In case you’re wondering, the word apocalypse literally means any sort of revelation, but it’s usually used to refer to the biblical text known as the Revelation of St. John, which portrays the end of the world.

Thus its metaphorical meaning, in the words of the New Oxford American Dictionary, is “an event involving destruction or damage on an awesome or catastrophic scale.”

We’re not quite convinced that this bug deserves quite such an, ahhhh, apocalyptic name, but we’re willing to concede that in a world where awesome can mean “quite good”, the name is probably acceptable, if not entirely unexceptionable.

The “Crop” in “aCropalypse”

The “crop” part of the name comes from the activity that is most likely to trigger the bug, dubbed CVE-2023-20136 in its Google incarnation: cropping photos or screenshots to remove sensitive or unwanted parts before you share them.

Loosely speaking, you can imagine that if you took, say, a 1080×1980 screenshot of your phone’s entire screen, you probably wouldn’t want to post the entire image online, or to send the whole thing to a friend.

Most people would prefer to crop off at least the top of the screenshot, thus removing details such as the name of their mobile provider, the date and the time.

And if you were snapping, say, an email or a social media posting in the middle of a list, you’d almost certainly want to obscure the emails or postings that appeared just above or just below the portion of interest.

Even after croppping the image, you might also want to redact parts of it (a jargon word meaning to obscure or censor part of a document), for example by dropping a black box over the sender’s name, email address, telephone number, or whatever.

At any rate, you might assume that if you chopped out chunks of the original, obscured some details with blocks of solid colour (which compress much more readily than regular image data), and saved the new image over the old one…

…that the new image would almost certainly be smaller, possibly much smaller, than the original.

Because of all the stuff you left out!

But that isn’t what happened on Google Pixel phones, at least until the March 2023 Android security update.

Overwritten but not truncated

The new, smaller, image file would be written over the start of the old one, but the file size would remain the same, and the now-redundant and unwanted data at the end of the original file would stay where it was.

If you sent that file to someone else and they opened it with a conventional image viewing or editing tool, their software would read the file until it reached a data chunk that said, “That’s it; you can stop now and ignore any trailing data in the file.”

In other words, the coding flaw that caused unwanted data to be left behind at the end of the file wouldn’t generally provoke any obvious errors, which presumably explains why the bug wasn’t spotted until recently.

But if the recipient opened it with a more inquisitive software tool, such as a hex editor or a cunningly modified image editor, anywhere from a few bytes to a vast amount of the original image would still be there, past the official end-of-image marker, waiting to be explored and potentially exposed.

Most screenshots are saved as PNG files, short for portable network graphics, and are internally compressed using a compression algorithm known commonly as deflate.

The left-over data therefore doesn’t look obviously like rows and columns of pixels, and it can’t be directly decompressed by conventional unpacking tools, which will consider the compressed data stream to be corrupt, which it is, and will usually refuse to try unpacking it at all.

But deflate compression typically squeezes its input data as a sequence of blocks, looking back only so far in the input for repeated text (32 Kbytes at most, for matches at most 258 bytes long) in order to reduce the amount of memory needed to run the algorithm.

Those restrictions aren’t just down to the fact that the format dates back to the 1990s, when memory space was much more precious than today.

By “resynchronising” the compressor on a regular basis, you also reduce the risk of losing absolutely everything in a compressed file if even just a few bytes at the start were to get corrupted.

Substantial reconstruction may be possible

This means that image files stored in compressed PNG format can often be substantially reconstructed, even if sizeable chunks of the original are overwritten or otherwise destroyed.

And if you’re talking about image fragments that can be reconstructed from a file that’s been cropped or redacted…

…there’s clearly a chance that the left-over data at the end, that was supposed to be chopped off, will contains recoverable image portions revealing the very parts you intended to remove permanently from the image!

You could get lucky, to be sure: if the image is stored row-by-row (so the data for top of the image is close to the start of the file, and the bottom is at the end), and you crop off the top of the image, you will probably end up with a new image consisting of the bottom half of the old image in the “official” part of the file, and the bottom half repeated in the left-over data that was supposed to be chopped off but wasn’t.

But if you crop off the bottom of the image, the new file will have the old top part “officially” re-encoded and written over the start, and the cropped-off bottom half of the image left behind exactly where it was before, in the unofficial end of the new file, waiting to be extracted by an attacker.

Windows 11 affected too

Well, the deal is that this problem of files not being truncated when they are replaced with new version also applies on Windows 11, where the Snipping Tool, like the Google Pixel Markup app, will let you crop an image without correctly cropping the file it’s saved into.

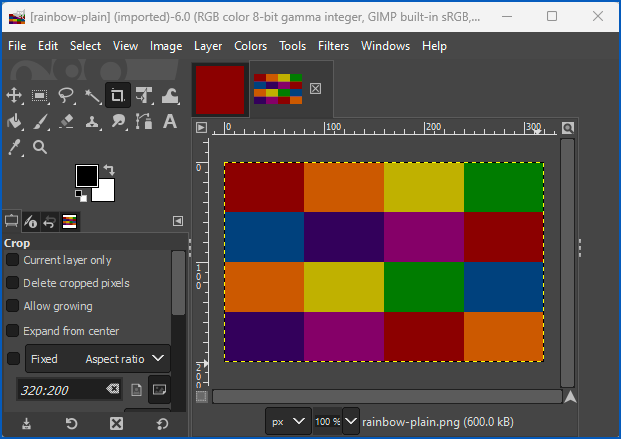

For example, here’s a PNG file we created with GIMP, and saved with a minimal set of headers and no compression:

The file is 320×200 pixels of 8-bit RGB data (three bytes per pixel), so the file is 320x200x3 bytes long (192,000), plus a few hundred bytes of header and other limited metadata, for a total size of 192,590 bytes.

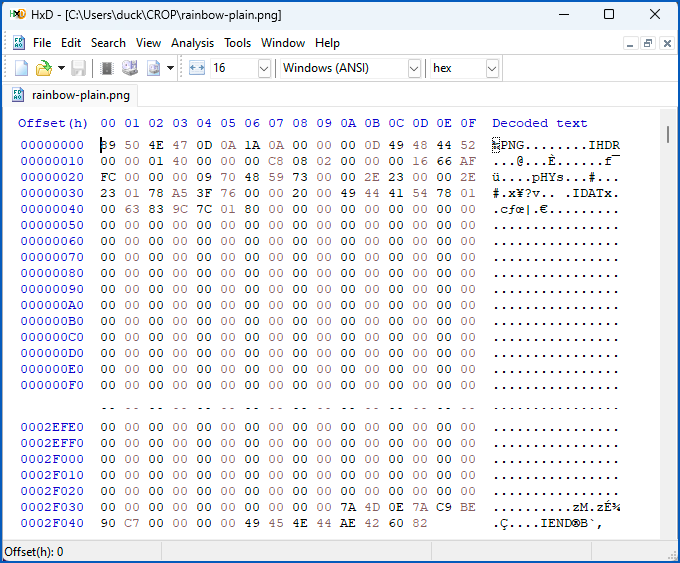

In the illustrative hex dump below, you can see that the data is 0x20F04E bytes long, which is 192,590 in decimal:

We then cropped it as small as the Snipping Tool will allow (48×48 pixels seems to be the minimum) and saved it back over itself, but the “new” file ended up the same size as the uncompressed 320×200 file!

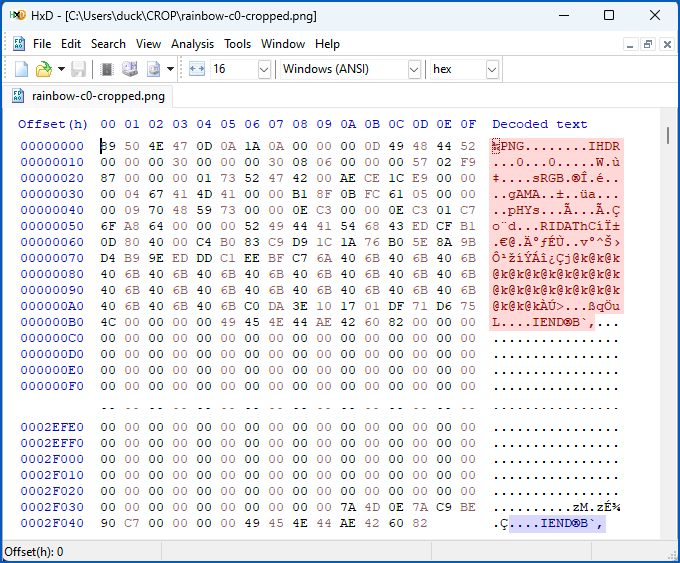

In the hex dump below, the portion highlighted in pink at the top is the entirety of what the cropped file is supposed to contain, at 0xBD bytes long, or 189 in decimal.

The new data concludes with an IEND data block, which is where the new file should end, but you can see it continues with the left-over data from before, ultimately finishing with a duplicate-but-now-redundant IEND block that has been carried over from the old file, along with almost all of its image data:

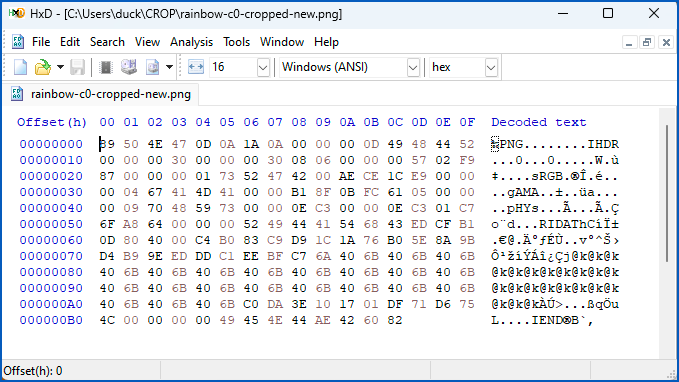

When we used the Save button to write it out under a brand new filename, the compressed 48×48 file did indeed come out at just 189 bytes long.

Note how the data in the file matches the 189 bytes highlighted in pink in the previous image:

The bug, therefore, is that saving a file back over an existing filename doesn’t truncate the old file first, and doesn’t create a new file with the expected size.

Simply put, the cropped file is partially overwritten, rather than actually replaced.

As mentioned above, we’re guessing that no one spotted this flaw until now because image viewing and editing programs read up until the first IEND tag (you can see this at the bottom right corner of the screenshot above), and silently ignore all the extra stuff at the end without reporting any anomalies or errors.

What to do?

- If you’re a Windows 11 user. Always save cropped files created with the Snipping Tool under a new filename, so there is no original content in it that can get left behind.

- If you’re a programmer. Review everywhere you create “new” files by overwriting old ones to make sure you really are truncating the original files when you open them for rewriting. Or only ever create new files by saving them to a genuinely new file first (use a securely-generated unique filename), then explicitly deleting the original file and renaming the new one.

By the way, we tested Microsoft Paint, and as far as we can see, that program will create cropped files with no left-over data from before, whether you use Save (to replace an existing file) or Save As (to produce a new one).

LEARN ABOUT FILE OPEN MODES FOR YOURSELF

Compile this code and run it.

On Windows, you can use minimalisti-C, our own curated build of the free Tiny C Compiler, if you don’t have a development system installed.

It’s under 500 KBytes in size (!), including full source code, compared to gigabytes each for Visual Studio or Clang for Windows.

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

char* az = "ABCDEFGHIJLKMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ";

int fd;

// Create a file with A-Z in it

// Octal 0666 means "read/write for everyone"

// O_CREAT means create if needed

fd = open("blah1.txt",O_WRONLY+O_CREAT,0666);

write(fd,az,26);

close(fd);

// Create another file with A-Z in it

fd = open("blah2.txt",O_WRONLY+O_CREAT,0666);

write(fd,az,26);

close(fd);

// Write 10 bytes without O_TRUNC set

// The left-over 16 bytes should remain

fd = open("blah1.txt",O_WRONLY);

write(fd,"----------",10);

close(fd);

// Write 10 bytes *with* O_TRUNC set

// Left-over old data should be chopped off

fd = open("blah2.txt",O_WRONLY+O_TRUNC);

write(fd,"==========",10);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

Note the different between opening an existing file for writing (O_WRONLY) with and without setting the O_TRUNC flag.

Print out the contents of blah1.txt and blah2.txt after running the test program:

C:\Users\duck\CROP> petcc64 -stdinc -stdlib test.c

Tiny C Compiler - Copyright (C) 2001-2023 Fabrice Bellard

Stripped down by Paul Ducklin for use as a learning tool

Version petcc64-0.9.27 [0006] - Generates 64-bit PEs only

-> t1.c

-> c:/users/duck/tcc/petccinc/fcntl.h

. . . .

-> C:/Windows/system32/msvcrt.dll

-> C:/Windows/system32/kernel32.dll

-------------------------------

virt file size section

1000 200 2a0 .text

2000 600 1cc .data

3000 800 18 .pdata

-------------------------------

<- t1.exe (2560 bytes)

C:\Users\duck\CROP> t1.exe

C:\Users\duck\CROP>dir blah*.txt

Volume in drive C has no label.

Volume Serial Number is C001-D00D

Directory of C:\Users\duck\CROP

22/03/2023 07:20 pm 26 blah1.txt

22/03/2023 07:20 pm 10 blah2.txt

2 File(s) 36 bytes

C:\Users\duck\CROP> type blah1.txt

----------KLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

C:\Users\duck\CROP> type blah2.txt

==========

Ralph

Wow, I never thought Microsoft would have have used the same, uh, questionable technique… Not that I hold them in much higher esteem than Google, but when prensented this way, I wonder why anyone thought it would be a good idea. Plus imaging the wasted disk space from all the not-actually-cropped pictures…

Paul Ducklin

Th irony is that back in the old days, when we were taught not to assume that disk writes would be as good as 100% reliable, the concept of “create a new file then delete the old one and rename the new one to replace the old one” was pretty usual, just in case something went wrong, so you had some chance of recovering… even though we were truly short of disk space, and could have done without temporarily having two copies of the file every time we saved it.

(Some programs offered “fast saves”, which re-used the old file’s disk space if possible, but they were rarely on by default and came with appropriate warnings.)

Now that flash storage is reliable enought you can just overwrite the old file and assume the new one won’t corrupt anything and everything will be fine… we’ve got more than enough CPU power, disk speed and disk space to follow the old-school way.

Progress, I suppose. Of a sort. To be fair, I guess that modern phones and laptops are also largely immune to temporry power glitches, a worrying problem last century, because they effectively have thir own built-in UPSes thanks to modern batteries. But you do need to be careful with those O_TRUNC flags!

Alasdair Hepburn

I remember the “fast save” (which also meant “slow load”), with Word 6.0 having it. The Fast save would append any changes to the document onto the end of the file. Since a big document would be saved initially, and then only a couple of sentences might be edited, then it was only those changes that were being saved.

On document load, however, it had to read the whole of the original file, and then incrementally apply all the edits (once “slow load”)

When Word 6.0 first came out, it had a bug that meant that a fast saved file would often only be read to the end of the original document, which meant that all changes were now inaccessible.

Worse, many people using a company template will take an existing document, save it as a new name and then delete all the old text, so that the formatting is all set up. Under the Word 6.0 bug, that sometimes meant that the new document had effectively been replaced by the old one when it was next loaded up.

Not surprisingly, Word 6.0a was soon released to fix that bug.

Of course, once people stopped using floppy disks, the utility of fast save diminished (though it remained the default setting in Word for some years afterwards,) It was a potential security risk in precisely the same way that these image bugs are – the file could potentially contain information that had been deleted.

Anonymous

absoljutely -> absolutely

siklently -> silently

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks.

Laurence Marks

Excuse me! “Redact” is not jargon. Etymology: From Old French redacter, from Latin redactus, perfect passive participle of redigō (“drive, lead, collect, reduce”), from re- (“back”) + agō (“put in motion, drive”).

Paul Ducklin

It’s used as jargon these days, at least in cybersecurity. I’m OK with calling it jargon, but I get your point.

sebster

Trimming videos in iOS also did a similar thing.

What I’ve noticed: When you record the screen, trim the video to some seconds within, crop some contents on screen, and then send it to someone else on Facebook messenger or something, the original video is sent even tho the Photos app shows a cropped and trimmed version of the video.

Solution was to always “Save as new video”

Laurence Marks

Surprising that the bug does not appear in the Windows 10 Snipping Tool–or was it simply not investigated? I can’t see any reason why the the code would change for an app like this.

Paul Ducklin

I don’t know. I don’t have a Windows 10 build handy to take a look. I’m guessing either that the Snipping Tool got a facelift that was more of a rewrite than just a few code tweaks, so the W11 version is vulnerable but the W10 one is not, or that the W10 version is in fact vulnerable.

Any readers with W10 care to test and report back? Just grab a full-screen screenshot, check its filesize, crop it as tiny as you can with the Snipping Tool, hit accept/save (same filenames) and see if the file has got smaller.

If it is the same size as before but now shows only the cropped data when you preview it in Explorer… that’s the bug right there.

Alex

Hi Paul,

Just tried this on Windows 10 using the new “Snip & Sketch” app which is the newer version of Snipping Tool and took a full screenshot at 381KB, cropped to smallest I could and saved/overwrote the file, and it was still in fact 381KB which would suggest also an issue on W10.

You cannot crop in the older Snipping Tool in W10 so cannot test it, could crop using the “Photos” app which is not relevant.

Kind Regards,

Alex

Alex

It does appear in the newer Snip & Sketch Windows 10 app. Cannot crop in the older Snipping Tool in W10 that I could see

Paul Ducklin

Thanks for the report!

Techno

Thankfully, I am in the habit of saving the cropped image as a new file, in case I make a mistake and need the original again.

John

Well I didnt expect to come back and see yesterdays problem being detected in other applications quite so quickly. This can is definitely opened!.

Can you confirm if this bug in “Snip & Sketch” is due to it also calling the (new) Java library routine in which case there is some small excuse, or is it due to incorrect programming in some other language?

Paul Ducklin

The Windows 11 Snipping Tool isn’t written in Java. At a glance I would say it is written in C++, presumably using the MFC libraries.

Anon

This is probably a known “vulnerability” that can be used by forensics folks if needed. It wouldn’t surprise me if this was known about the entire time and by design…. it just wasn’t publicly disclosed. Maybe we will never know.

Paul Ducklin

Seems an unlikely way to program in a deliberate bug for forensics folks, given how imprecise it is as a “feature”.

If you were going to sneak a secret feature into Windows for law enforcement, wouldn’t you code it so that the software worked via a “temporary” copy of the original file that “accidentally” didn’t get deleted afterwards, thus retaing the entire content of the initial file in a reliable way?

(Or would you consider that too obvious compared to leaving most of the original file behind in the new one?)

Also, Hanlon’s Razor (q.v.)…

Paul Dodd

Just imagine how many unnecessary exabytes were (and are) sent over the internet. Luckily, most are JPEGs …

Paul Ducklin

As an interesting aside, contemporary screenshot tools typically produce PNG files.

Firstly, the compression is lossless, and screenshots might as well be pixel-perfect, now that we all have LCD screens that are themselves essentially pixel-perfect.

Secondly, JPEG compression handles sharp, high-contrast edges really badly (it’s basically to do with the cosine function), and Latin text is awash in vertical lines where pixel X is #FFFFFF/white and pixel X+1 is #000000/black. This typically causes noisy “digital dandruff” around every character that messes up contrast and sharpness right where it’s visually most intrusive.

Thirdly, screenshots, notably if they’re showing an app with at least some Latin text it it, often end up smaller (sometimes much smaller!) when compressed line-by-line in PNG format than when handled by a JPEG-style “zigzag round the image” compressor that was designed for photographic images. (The P in JPEG stands for photographic).