Google has just revealed a fourfecta of critical zero-day bugs affecting a wide range of Android phones, including some of its own Pixel models.

These bugs are a bit different from your usual Android vulnerabilities, which typically affect the Android operating system (which is Linux-based) or the applications that come along with it, such as Google Play, Messages or the Chrome browser.

The four bugs we’re talking about here are known as baseband vulnerabilities, meaning that they exist in the special mobile phone networking firmware that runs on the phone’s so-called baseband chip.

Strictly speaking, baseband is a term used to describe the primary, or lowest-frequency parts of an individual radio signal, in contrast to a broadband signal, which (very loosely) consists of multiple baseband signals adjusted into numerous adjacent frequency ranges and transmitted at the same time in order to increase data rates, reduce interference, share frequency spectrum more widely, complicate surveillance, or all of the above. The word baseband is also used metaphorically to describe the hardware chip and the associated firmware that is used to handle the actual sending and receving of radio signals in devices that can communicate wirelessly. (Somewhat confusingly, the word baseband typically refers to the subsystem in a phone that handles conecting to the mobile telephone network, but not to the chips and software that handle Wi-Fi or Bluetooth connections.)

Your mobile phone’s modem

Baseband chips typically operate independently of the “non-telephone” parts of your mobile phone.

They essentially run a miniature operating system of their own, on a processor of their own, and work alongside your device’s main operating system to provide mobile network connectivity for making and answering calls, sending and receiving data, roaming on the network, and so on.

If you’re old enough to have used dialup internet, you’ll remember that you had to buy a modem (short for modulator-and-demodulator), which you plugged either into a serial port on the back of your PC or into an expansion slot inside it; the modem would connect to the phone network, and your PC would connect to the modem.

Well, your mobile phone’s baseband hardware and software is, very simply, a built-in modem, usually implemented as a sub-component of what’s known as the phone’s SoC, short for system-on-chip.

(You can think of an SoC as a sort of “integrated integrated circuit”, where separate electronic components that used to be interconnected by mounting them in close proximity on a motherboard have been integrated still further by combining them into a single chip package.)

In fact, you’ll still see baseband processors referred to as baseband modems, because they still handle the business of modulating and demodulating the sending and receiving of data to and from the network.

As you can imagine, this means that your mobile device isn’t just at risk from cybercriminals via bugs in the main operating system or one of the apps you use…

…but also at risk from security vulnerabilities in the baseband subsystem.

Sometimes, baseband flaws allow an attacker not only to break into the modem itself from the internet or the phone network, but also to break into the main operating system (moving laterally, or pivoting, as the jargon calls it) from the modem.

But even if the crooks can’t get past the modem and onwards into your apps, they can almost certainly do you an enormous amount of cyberharm just by implanting malware in the baseband, such as sniffing out or diverting your network data, snooping on your text messages, tracking your phone calls, and more.

Worse still, you can’t just look at your Android version number or the version numbers of your apps to check whether you’re vulnerable or patched, because the baseband hardware you’ve got, and the firmware and patches you need for it, depend on your physical device, not on the operating system you’re running on it.

Even devices that are in all obvious respects “the same” – sold under the same brand, using the same product name, with the same model number and outward appearance – might turn out to have different baseband chips, depending on which factory assembled them or which market they were sold into.

The new zero-days

Google’s recently discovered bugs are described as follows:

[Bug number] CVE-2023-24033 (and three other vulnerabilities that have yet to be assigned CVE identities) allowed for internet-to-baseband remote code execution. Tests conducted by [Google] Project Zero confirm that those four vulnerabilities allow an attacker to remotely compromise a phone at the baseband level with no user interaction, and require only that the attacker know the victim’s phone number.

With limited additional research and development, we believe that skilled attackers would be able to quickly create an operational exploit to compromise affected devices silently and remotely.

In plain English, an internet-to-baseband remote code execution hole means that criminals could inject malware or spyware over the internet into the part of your phone that sends and receives network data…

…without getting their hands on your actual device, luring you to a rogue website, persuading you to install a dubious app, waiting for you to click the wrong button in a pop-up warning, giving themselves away with a suspicious notification, or tricking you in any other way.

18 bugs, four kept semi-secret

There were 18 bugs in this latest batch, reported by Google in late 2022 and early 2023.

Google says that it is disclosing their existence now because the agreed time has passed since they were disclosed (Google’s timeframe is usually 90 days, or close to it), but for the four bugs above, the company is not disclosing any details, noting that:

Due to a very rare combination of level of access these vulnerabilities provide and the speed with which we believe a reliable operational exploit could be crafted, we have decided to make a policy exception to delay disclosure for the four vulnerabilities that allow for internet-to-baseband remote code execution

In plain English: if we were to tell you how these bugs worked, we’d make it far too easy for cybercriminals to start doing really bad things to lots of people by sneakily implanting malware on their phones.

In other words, even Google, which has attracted controversy in the past for refusing to extend its disclosure deadlines and for openly publishing proof-of-concept code for still-unpatched zero-days, has decided to follow the spirit of its Project Zero responsible disclosure process, rather than sticking to the letter of it.

Google’s argument for generally sticking to the letter and not the spirit of its disclosure rules isn’t entirely unreasonable. By using an inflexible algorithm to decide when to reveal details of unpatched bugs, even if those details could be used for evil, the company argues that complaints of favouritism and subjectivity can be avoided, such as, “Why did company X get an extra three weeks to fix their bug, while company Y did not?”

What to do?

The problem with bugs that are announced but not fully disclosed is that it’s difficult to answer the questions, “Am I affected? And if so, what should I do?”

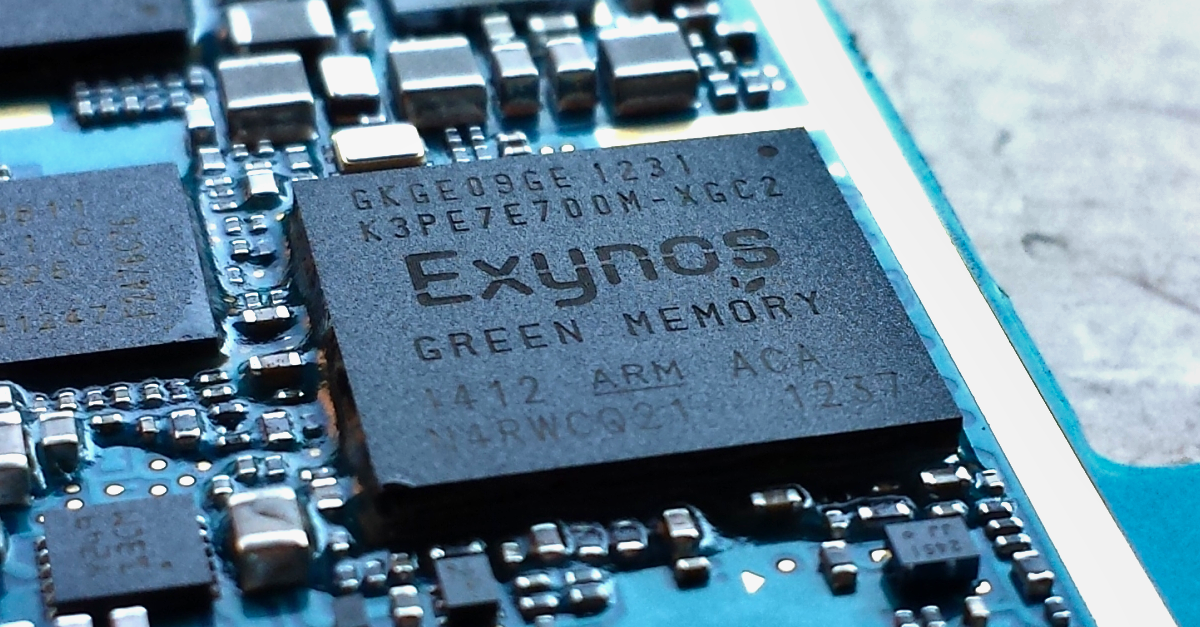

Apparently, Google’s research focused on devices that used a Samsung Exynos-branded baseband modem component, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the system-on-chip would identify or brand itself as an Exynos.

For example, Google’s recent Pixel devices use Google’s own system-on-chip, branded Tensor, but both the Pixel 6 and Pixel 7 are vulnerable to these still-semi-secret baseband bugs.

As a result, we can’t give you a definitive list of potentially affected devices, but Google reports (our emphasis):

Based on information from public websites that map chipsets to devices, affected products likely include:

- Mobile devices from Samsung, including those in the S22, M33, M13, M12, A71, A53, A33, A21s, A13, A12 and A04 series;

- Mobile devices from Vivo, including those in the S16, S15, S6, X70, X60 and X30 series;

- The Pixel 6 and Pixel 7 series of devices from Google; and

- any vehicles that use the Exynos Auto T5123 chipset.

Google says that the baseband firmware in both the Pixel 6 and Pixel 7 was patched as part of the March 2023 Android security updates, so Pixel users should ensure they have the latest patches for their devices.

For other devices, different vendors may take different lengths of time to ship their updates, so check with your vendor or mobile provider for details.

In the meantime, these bugs can apparently be sidestepped in your device settings, if you:

- Turn off Wi-Fi calling.

- Turn off Voice-over-LTE (VoLTE).

In Google’s words, “turning off these settings will remove the exploitation risk of these vulnerabilities.”

If you don’t need or use these features, you may as well turn them off anyway until you know for sure what modem chip is in your phone and if it needs an update.

After all, even if your device turns out to be invulnerable or already patched, there’s no downside to not having things you don’t need.

Featured image from Wikipedia, by user Köf3, under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence.

Larry Marks

AWK!! Incomplete information! I understand “Turn off Wi-Fi calling.” But I do not understand “Turn Voice-over-LTE (VoLTE).” There is a missing word between “Turn” and “Voice.” Is it “On” or “Off?” HELP!

My carrier requires VOLTE. To use VoIP when out of the country, I need Wi-Fi calling. Is it time to give up my beloved Essential PH-1, one of the best Android phones ever produced?

Paul Ducklin

Off. Fixed now…thanks.

Paul Ducklin

The Essential PH-1 is based on the Qualcomm Snapdragon system-on-chip… as far as I can tell, Snapdragons have their own modem that isn’t Exynos-branded. (Samsung itself has some models that are Exynos-based in some markets and Snapdragon-based in others, and the Snapdragons are apparently unaffecfed. That doesn’t mean there are no bugs in Snapdragon modems, just that they weren’t studied by Google in this research, and presumably use a different firmware codebase, and are therefore unlikely to have the same bugs by chance.)

eug.smiley

“In the meantime, these bugs can apparently be sidestepped in your device settings, if you:

Turn off Wi-Fi calling.

Turn Voice-over-LTE (VoLTE).”

This last statement makes no sense. Turn Off VoLTE or Torn on VoLTE?

Paul Ducklin

Turn them both off… as in the sentence following: “In Google’s words, turning off these settings will remove … the risk.”

I’ve added the missing word and repeated the link to the Google bug report blog. HtH.

Mark

– The March update is not yet available for the Pixel 6 line of devices

– There is no control to turn off VoLTE on these devices

I have turned off the *power* switch until the March update arrives (supposed to be Monday Mar 20)

I would love to have someone with real knowledge let me know if Airplane mode or just removing the sim would keep me safe on my Pixel 6a

Paul Ducklin

That’s a tricky question that I can’t answer…

…but here are my guesses:

* Airplane mode. I can’t see how this attack could be used when all radio sending and receiving capabilities are turned off. Of course, you won’t be able to use non-baseband connectivity such as Wi-Fi or Bluetooth either, so that’s somewhat useless. I suspect that you could hook up your phone to the internet via a USB cable and the Android Debug Bridge, using your laptop or desktop as a wired router, but I have never tried it.

* SIMless mode. It sounds as though this would protect you, assuming that you can turn off Voice over Wi-Fi explicitly and rely on the absent SIM implicitly turning off VoLTE, by preventing you from having an LTE connection.

As for turning off VoLTE explicitly… from what I’m seeing online, some carriers effectively have it forcibly turned on and so there’s no option to turn it off. Perhaps you could contact your carrier and see if they can turn it off temporarily?

Also, is there an option (or a temporary SIM swap) by means of which you could temporarily drop back to 3G only, thus allowing you still to make calls and get SMSes if needed, but not to get LTE-enabled connections at all?

Paul Ducklin

Hmm. I just checked the factory images and there are full March 2023 images for at least the Pixel 4a, 5 and 7 devices…

…but nothing past February 2023 for the Pixel 6, 6a or 6 Pro.

It’s a bit rotten of Google to write that the Pixel 6 series has been patched if even the official Google factory image site doesn’t have the actual patched code published yet.

Makes you wonder just how gracious Google would have been with the bug disclosure deadline if all their own devices had patches not just coded but also actually shipping…

Pete

I can turn off VoLTE in the Internet settings of the Pixel 6 Pro.

Paul Ducklin

May depend on you carrier rather than the Pixel phone version…

Tyson Friedrichsen

Well then I already might have had something like this affect my pixel 6… my social media. Having spent so much money on these phones and services, I just recently had all of my social media compromised. I lost money and my entire platform I use for my business selling art!!! Is this why?? So what is Google going to do to compensate all the people affected by this??? Google needs to be accountable for this!

Paul Ducklin

Considering that Google hasn’t disclosed the bug details publicly; considering that there is no evidence that anyone else has discovered this flaw; given that there are dozens of other likely ways that your social media accounts could have been compromised; and given that you have offered no evidence at all of what actually happened anyway…

…all I can say is, “Good luck holding Google responsible.”

Pete

If I understand the description correct, the potential of the bug is on intercepting network traffic (and calls, SMS). If Tyson is using any up-to-date social Media platform they would probably have encrypted traffic (between Tyson’s browser/app and the sm-server), so there wouldn’t even be a potential that the bug is related to Tyson’s troubles?

Only possible scenario could be to catch an sms-2fa code (for authentication or password reset), but this would probably be either of limited use or noticed quite fast.

Paul Ducklin

I deliberately avoided saying exactly what a crook might do with this bug (or, more precisely, how far into the phone they might be able to get) because Google deliberately didn’t give sufficient detail to do so. It’s possible that the remote code execution Google mentions could go as far as implanting code on the CPU itself; it might be just that the remote code that’s implanted could only run in the baseband chip…

Like you, I did ponder the issue of catching 2FA tokens or reading SMSes. How easy might that be with code implanted in the baseband?

Although stealing a 2FA code is generally not enough on its own to crack someone’s account, it would be a serious matter if an attacker could effectively do a “SIM swap” to steal your messages *without actually swapping your SIM*. (At least you get a warning for the latter,because the SIM swap deactivates your SIM and thus your phone goes dead, which you’re likely to notice.)

There just isn’t enough to go on right now, which is why I just suggested that various levels of intrusion might be possible, as a bit of an incentive to patch,

(I didn’t realise, though, that Google’s claims to have patched the Pixel 6 didn’t actually mean you could go and download those patches right away.)

JC

My Samsung A53 5G in mobile network settings has VoLTE Calls Sim 1

Use 4G data networks for calls whenever possible .

is this what should be turned off ?

Paul Ducklin

It sounds like it… anyone care to confirm?

Jc

Has this been patched with March updates?

Samsung

one UI version 5.1

Build Number : A536BXXS5CWB6

Android version : T(Android 13)

Release Date : 2023-03-14

Security patch level : 2023-03-01

Paul Ducklin

You probably need to ask Samsung for clarification, or find their latest release notes and see which CVEs are listed as fixed.

Mark

It sounds like CVE-2022-20443 won’t be patched until next month