Black Friday is behind us, that football thing they have every four years is done and dusted (congratulations – spoiler alert! – to Argentina), it’s the summer/winter solstice (delete as inapplicable)…

…and no one wants to get locked out of their social media accounts, especially when it’s the time for sending and receiving seasonal greetings.

So, even though we’ve written about this sort of phishing scam before, we thought we’d present a timely reminder of the kind of trickery you can expect when crooks try to prise loose your social media passwords.

We clicked through for you

Because a picture is supposed to be worth 1024 words, we’ll be showing you a sequence of screenshots from a recent social media scam that we ourselves received.

Simply put, we clicked through so you don’t have to.

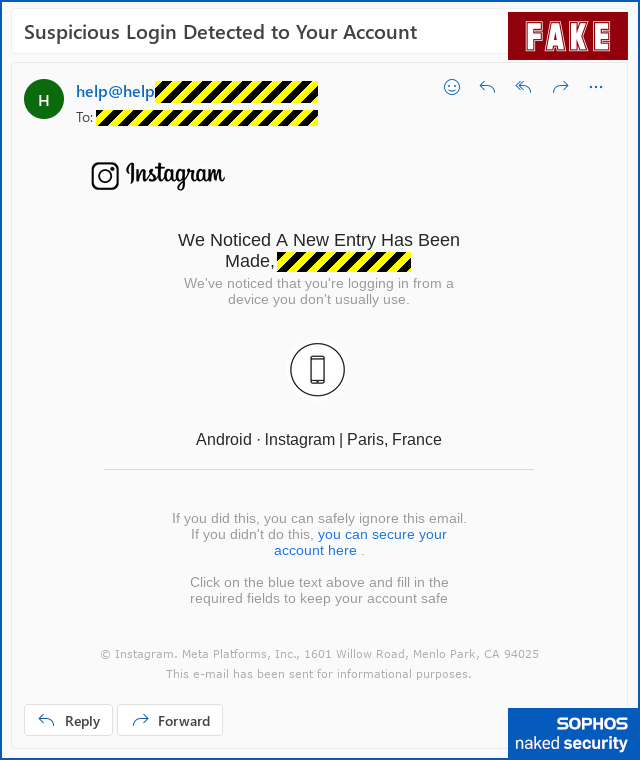

This one started with an email that pretends to be looking out for your online safety and security, though it’s really trying to undermine your cybersecurity completely:

Even though you may have received similar-looking emails from one or more of your online account providers in the past, and even though this one doesn’t have any glaring spelling or grammatical errors…

…if fact, even if this really were a genuine email from Instagram (it isn’t!), you can protect yourself best simply by not clicking on any links in the email itself.

If you have your own bookmark for Instagram’s help pages, researched and saved when you weren’t under any cybersecurity pressure, you can simply navigate to Instagram directly, all by yourself.

That way, you neatly avoid any risk of being misdirected by the blue text (the clickable link) in the email, no matter whether it’s real or fake, working or broken, safe or dangerous.

The trouble with clicking through

If you do click through, perhaps because you’re in a hurry, or you’re worried about what might have happened to your account…

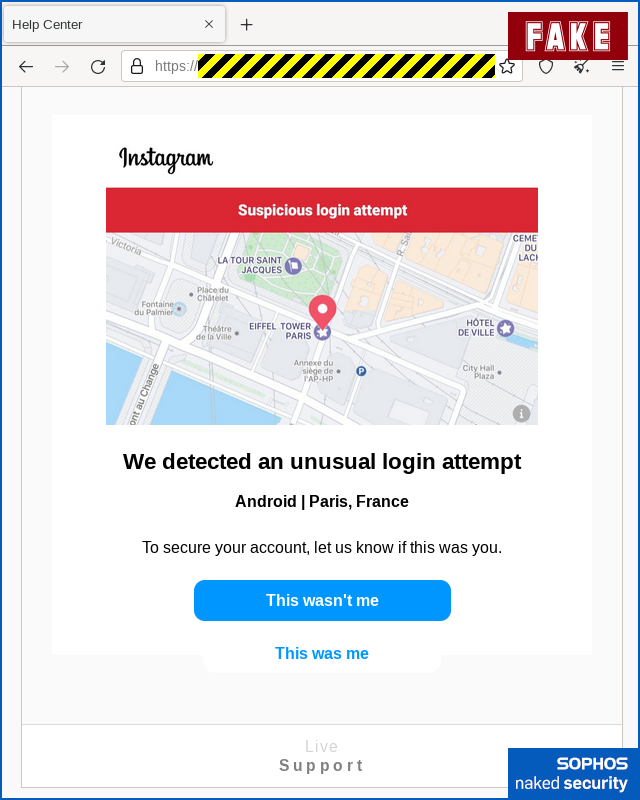

…well, that’s when the trouble starts, with a fake page that looks realistic enough.

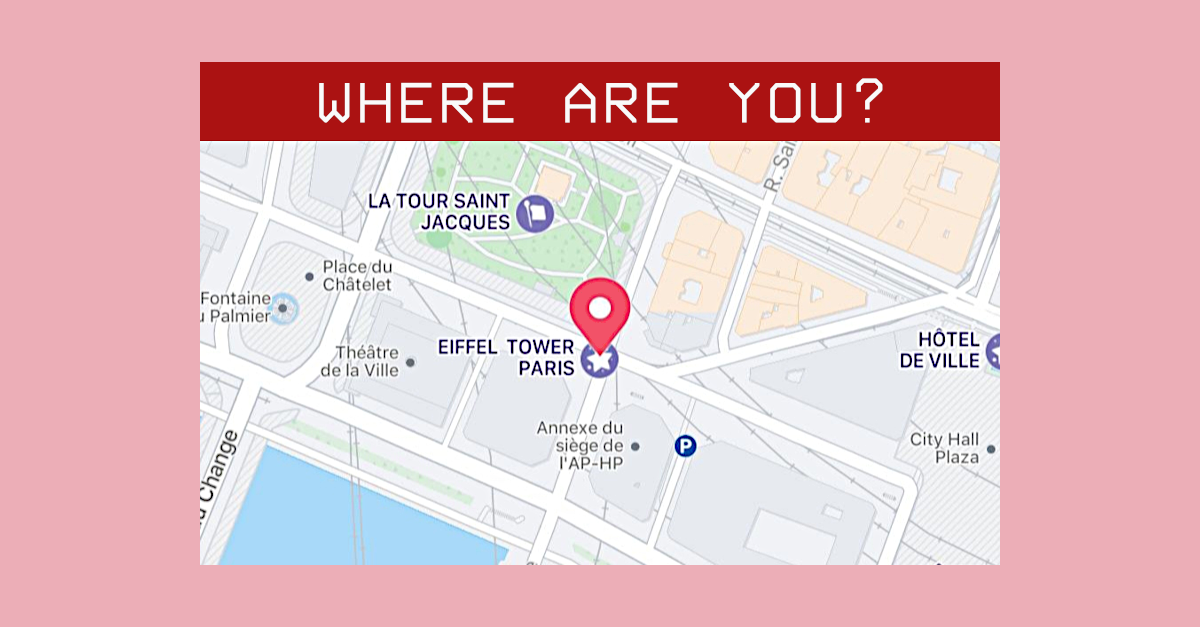

The crooks are pretending that someone, presumably someone enjoying a vacation of their own in Paris, tried to login to your account:

You ought to be suspicious of the server name that shows up in the address bar in this scam (we’ve redacted it here, though it wasn’t anything like instagram.com), but we can understand why so many users get caught out by fake domains.

That’s because lots of legitimate online services make it as good as impossible to know what to expect in your address bar these days, as Sophos expert (and popular Naked Security podcast guest) Chester Wisniewski explained back in Cybersecurity Awareness Month:

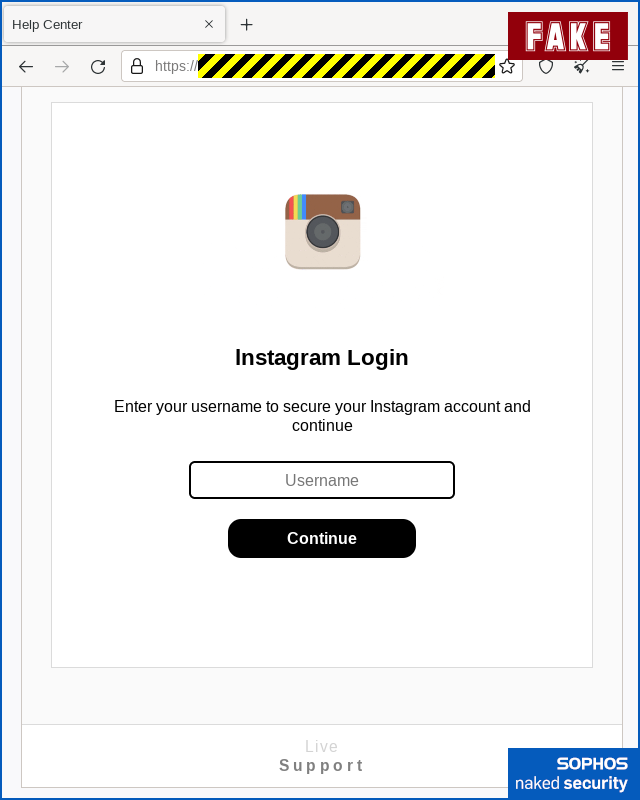

In this scam, whether you click [This wasn't me] or [This was me], the crooks take you down the same path, asking first for your username:

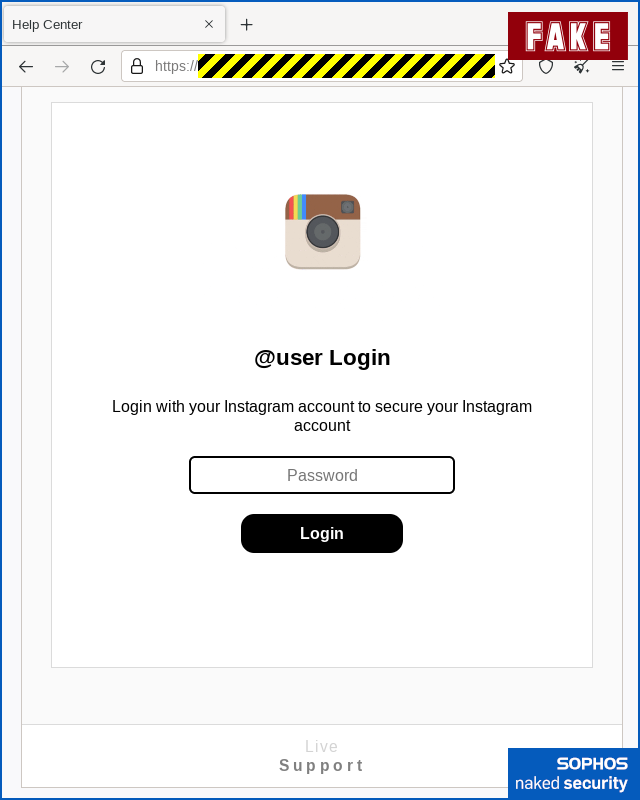

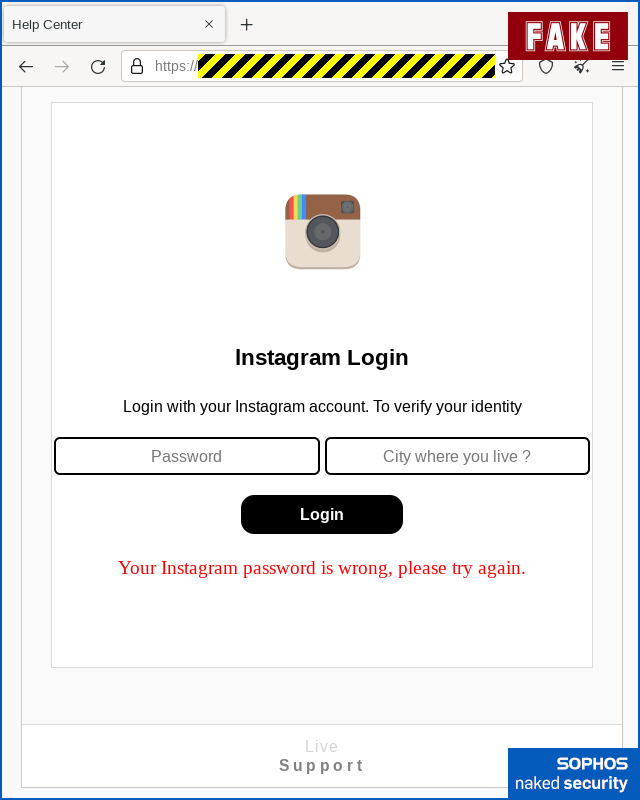

The wording has started to get a bit clumsy on the next screen, where the crooks are going for your password, but it’s still believable enough:

A fake mistake

The scammers then pretend you made a mistake, asking you not only to type in your password a second time, but also to add a tiny bit more personal information about your location:

Not every phishing scam of this sort uses the “your password is wrong” trick, but it’s quite common.

We suspect that the crooks do this because there’s dubious security advice still going around that says, “You can easily detect a scam site by deliberately putting in a fake password first; if the site lets you in anyway, then obviously the site doesn’t know your real password.”

If you follow this advice (please don’t – it only ever gives you a false sense of security), you might jump to the dangerous conclusion that the site must surely know your real password, and must therefore be genuine, given that it seems to know that you put in the wrong password.

Of course, the crooks can safely say that you got your password wrong the first time, even if you didn’t.

If you deliberately got your password wrong, the crooks can simply pretend to “know” it was wrong in order to trap you into continuing with the scam.

But if you’re sure you really did put in the right password, and therefore the fake error message makes you suspicious…

…it’s too late, because the crooks have already scammed you.

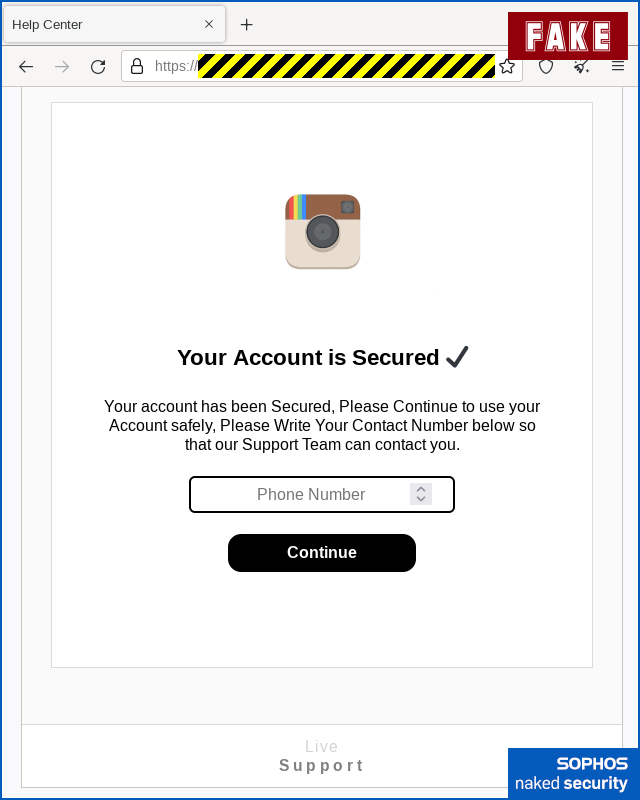

One last question

If you keep going, then the crooks try to squeeze you for one more piece of personal information, namely your phone number:

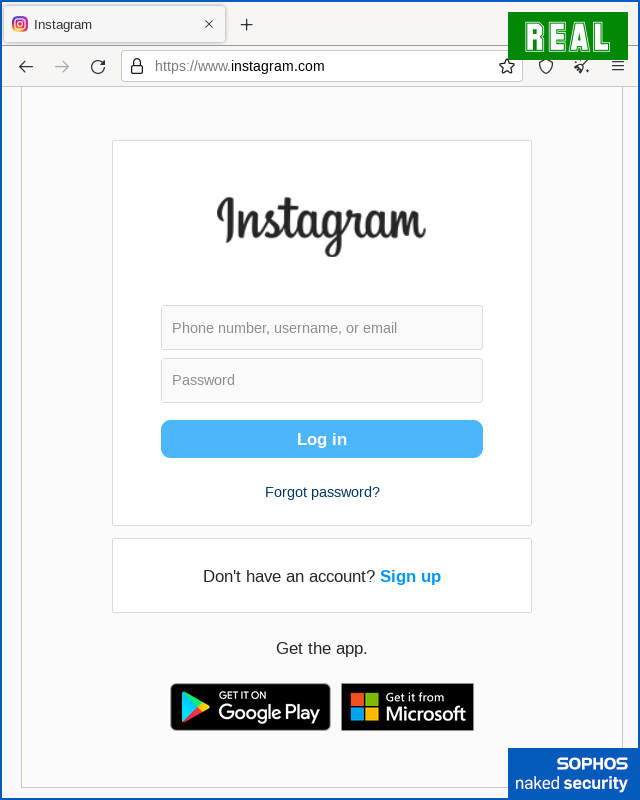

And to let you out of the scam gently, the crooks finish off by redirecting you to the genuine Instagram home page, as if to invite you to confirm that your account still works correctly:

What to do?

- Keep a record of the official “verify your account” and “how to deal with infringement challenges” pages of the social networks you use. That way, you never need to rely on links sent via email to find your way there in future. As well as fake login warnings like the one shown here, attackers often use concocted copyright violations, made-up breaches of your account’s Terms and Conditions, and other fake “problems” with your account.

- Pick proper passwords. Don’t use the same password as you do on any other sites. If you think you may have given away your password on a fake site, change it as soon as you can before the crooks do. Consider using a password manager if you don’t have one already.

- Turn on 2FA (two-factor authentication) if you can. This means that your username and password alone will not be enough to login, because you will need to include a one-time code, either every time, or perhaps only when you first try to use a new device. Although this doesn’t guarantee to keep the crooks out, because they may try to trick you into revealing your 2FA code as well as your password, it nevertheless makes things harder for an attacker.

- Don’t overshare. As much as it seems to be common to share a lot of your life on Instagram nowadays, you don’t have to give away everything about yourself. Also, think about who or what is in the background of your photos before you upload them, in case you overshare information about your friends, family or household by mistake.

- Stay vigilant. If an account or message seems suspicious to you, do not interact or reply to the account and do not click on any links they send you. If something seems too good to be true, assmue that it IS too good to be true.

- Consider setting your Instagram account to private. If you aren’t trying to be an influencer whom everyone can see, and if you use Instagram more as a messaging platform to keep touch with your close friends than as a way to tell the world about yourself, you may want to make your account private. Only your followers will be able to see yout photos and videos. Review your list of followers regularly and kick off people you don’t recognise or don’t want following you any more.

Right. Toggle the ‘Private account’ slider on.

- If in doubt, don’t give it out. Never rush to complete a transaction or confirm personal information because a message has told you you’re under time pressure. If you aren’t sure, ask someone you know and trust in real life for advice, so you don’t end up trusting the sender of the very message you aren’t sure you can trust. (And see the first tip above.)

Mr Charles R Dickinson

Why don’t you tell people to click on the To field to see the sender’s email address? I frequently get spam emails and I have yet to see a sender’s email address that looked anything like the business they are pretending to be from. Saves a lot of puzzling over content of the email. But otherwise I like your daily posts. I’ve been reading them since we started using your products twenty (or so) years ago.

Paul Ducklin

I assume you mean “From:”…

…well, the problems with trying to read anything into the “From:” header are twofold.

Firstly, a significant proportion (possibly the majority) of messages you get these days don’t originate from the business you are dealing with. Sometimes, even your own employer’s official correspondence will originate outside the company.

Support replies may come from an outsourcing company. Requests for quotation may come from some cloud service. HR directives from some external portal; your telephone usage data from a third party; your vacation notification from a fourth party; your utility company may have just been sold to a former competitor and use a weird mix of systems; and as for legitimate marketing messages, well they can and do come from an apparently inexhaustible supply of different domains.

Secondly, the “From:” field is basically part of the message itself, so it is entirely under the control of the sender. They can, quite literally, put anything in there that they like.

By all means look at the From: address… like spelling mistakes, if the crooks make an obvious mess of it, *make them pay for it* by deleting the message immediately.

But the reason I try to avoid making too much out of “From:” addresses, web links and spelling (grammar) errors is that they are notoriously fickle indicators of anything, taken on their own. So I’d rather teach people to see the bigger picture, and to know what to do even if none of the “obvious” telltales are present.

Simply put, too many good messages look bad (and people aren’t willing to live without them, so there is little incentive for senders to tighten up their behaviour), and it’s too easy for half-careful crooks to make bad messages look good, or at least not to have any of the common “indicators of compromise”.

Having said that, if you find that the From: field alone helps you deal with, say, 99% of the scams you get, then I would say you are doing well, as long as you don’t let yourself get drawn into assuming that the the 1% you don’t delete “off the bat” have actually passed any kind of useful test :-)

Anonymous

Sometimes the To: can be spoofed as well. As the article suggests the best way to confirm its legitimate is going to the website yourself through a trusted URL.

Paul Ducklin

Pretty much any field that’s denoted by “Shortish-String-Of-Chars” followed by COLON is an email header, and those appear inside the data transmitted as the email itself (what’s “inside the envelope”, to speak metaphorically).

Some email servers will check common header values to make sure they are sensible, and will block messages with headers that don’t look right, but that’s tricky in real life because lots of genuine emails include unlikely-looking headers.

One common trick we used to see a lot was an email sent to you that pretended to be From: (a real person in your company) and To: (some other real person in your company, but not you) that apparently raved about the secret hookup they’d just had at (some company business event) and that included one or more malware attachments claiming to be (some sort of saucy pics)…

…hoping you would assume you had received the message by mistake, and further hoping that your sense of corporate duty (what if there is whistleblowing to be done?!) would lure you into opening said files. For research purposes only, of course.

Charles Dickinson

In reply to Paul, Yes, I did of course mean From! Much of the spam I get is supposedly from BT. The spam I get is from something like ‘Support Desk’ or ‘Feedback’ followed by an email address which could be anything, but will not be j.bloggs@bt.com. If the spammer has full control, why not mention the supposed sender’s company in the email address? It’s an opportunity to reinforce your validity. Seems a no brainer to me. Having a ‘j.smith9999@gmail.com’ talking about my BT account is a real give away. Hence the usefulness of looking at the From field. I also appreciate your wanting readers to think about the unexpected email they have received. Merry Xmas!

R. Dale Barrow

It’s too bad the blink tag was deprecated (I know a long long time ago … ☺). You can’t stress enough: Don’t click on links in emails!

Paul Ducklin

As we warned last week in the podcast… where blink leads, be very, very afraid that marquee might follow.

(Actually, we didn’t exactly say that, but there words words to that sort of effect.)

R. Dale Barrow

I had forgotten about the marquee tag. Getting rid of it would be a sad day. I never found much use for it but IT STILL WORKS! Just think how evil blinking marquees would be.

Laura Bluestone

Don’t click on links in your emails. Don’t open up attachments unless you really know who they are from (and I’m still cautious about them). I scan everything. I also go to the website myself. If there is an issue, I’m likely to find it there and not in a fake email sending me to a fake malicious website. Scammers are everywhere during the holidays, so you can’t afford to be lackadaisical. Be ever vigilant.

Paul Ducklin

Yes, indeed.

And if the holiday season is what gives you that last push to get fired up about cybersecurity, keep doing it after the holidays are over. The crooks will still be at it in 2023 and beyond…

VJ

Instead of just sending them to spam and tolerating ever increasing real phishing scams as spam (as opposed to plain unwanted advertisements), I decided a while back to spend some time to deal with it by digging into the raw email and reporting abuse to all relevant parties … and it actually works from my experience! The amount has reduced significantly and I find if I don’t maintain this diligence, some parties (yes I know it’s automated mostly, but they’ll eventually remove my email from their potential victims list for whatever current campaign) the same ones tend to be persistent.

For the sender, I always use raw header. Ultimately the originating IP gets ’em. I use whois for the host and report it to the host, either through their web form or abuse email contact. If there’s an approving SPF domain for the DNS entry, the registrant there is complicit in the scam too.

Sometimes there will be other poritions of the header that contains the mass-mailer / emailing service used and sometimes with dedicated abuse tracking signatures, i.e. X-Mailer- … etc, so I report it to them too.

For the phishing url, even if a legitimate one is long, the real url will still have some indications of who it belongs to in the top level domain portion. Yes I checked the previous Sophos blog about that with the Microsoft-owned domains example and it’s something I already expect. Most I can still recognize such as Azure, etc. I can always double check with nslookup and/or whois / dns lookups

So for scam emails, again, I use nslookup to resolve the full domain to an IP address, then use whois or ipinfo.io to lookup the hoster, then report it to the hosting service.

If the phishing url uses a shortner, then I use urlexpander or any number of online expanders and get to the source phishing domain that way to lookup hosting info.

Most of the time it’s fruiteless to pursue the domain registrant since they’re hidden behind privacy protection proxy domain registration services, but I’ve come across a few careless or amateur scammers (probably obtaining my email from multiple leaked lists long ago) who put some cookie crumbs in the registrant email. This is a big opportunity and I was able to track 3 down personally so far. One to a VPS registriation with russian hosting and usiing Chinese QQ email haha. and other with common gmail address used to register other scam sits in the past, using reverse lookup, and another Indian dude who’s personal pages I found. He was so damn persistent I skipped the hosting providers he used and just sent email to him directly. That stopped the spam DEAD in its tracts.

It sounds like a lot work, but I’ve gotten so used to the workflow and In my case, all the effort really does pay off