A bug bounty hunter called David Schütz has just published a detailed report describing how he crossed swords with Google for several months over what he considered a dangerous Android security hole.

According to Schütz, he stumbled on a total Android lockscreen bypass bug entirely by accident in June 2022, under real-life conditions that could easily have happened to anyone.

In other words, it was reasonable to assume that other people might find out about the flaw without deliberately setting out to look for bugs, making its discovery and public disclosure (or private abuse) as a zero-day hole much more likely than usual.

Unfortunately, it didn’t get patched until November 2022, which is why he’s only disclosed it now.

A serendipitious battery outage

Simply put, he found the bug because he forgot to turn off or to charge his phone before setting off on a lengthy journey, leaving the device to run low on juice unnoticed while he was on the road.

According to Schütz, he was rushing to send some messages after getting home (we’re guessing he’d been on a plane) with the tiny amount of power still left in the battery…

…when the phone died.

We’ve all been there, scrabbling for a charger or a backup battery pack to get the phone rebooted to let people know we have arrived safely, are waiting at baggage reclaim, have reached the train station, expect to get home in 45 minutes, could stop at the shops if anyone urgently needs anything, or whatever we’ve got to say.

And we’ve all struggled with passwords and PINs when we’re in a rush, especially if they’re codes that we rarely use and never developed “muscle memory” for typing in.

In Schütz’s case, it was the humble PIN on his SIM card that stumped him, and because SIM PINs can be as short as four digits, they’re protected by a hardware lockout that limits you to three guesses at most. (We’ve been there, done that, locked ourselves out.)

After that, you need to enter a 10-digit “master PIN” known as the PUK, short for personal unblocking key, which is usually printed inside the packaging in which the SIM gets sold, which makes it largely tamper-proof.

And to protect against PUK guessing attacks, the SIM automatically fries itself after 10 wrong attempts, and needs to be replaced, which typically means fronting up to a mobile phone shop with identification.

What did I do with that packaging?

Fortunately, because he wouldn’t have found the bug without it, Schütz located the original SIM packaging stashed somewhere in a cupboard, scratched off the protective strip that obscures the PUK, and typed it in.

At this point, given that he was in the process of starting up the phone after it ran out of power, he should have seen the phone’s lockscreen demanding him to type in the phone’s unlock code…

…but, instead, he realised he was at the wrong sort of lockscreen, because it was offering him a chance to unlock the device using only his fingerprint.

That’s only supposed to happen if your phone locks while in regular use, and isn’t supposed to happen after a power-off-and-reboot, when a full passcode reauthentication (or one of those swipe-to-unlock “pattern codes”) should be enforced.

Is there really a “lock” in your lockscreen?

As you probably know from the many times we’ve written about lockscreen bugs over the years on Naked Security, the problem with the word “lock” in lockscreen is that it’s simply not a good metaphor to represent just how complex the code is that manages the process of “locking” and “unlocking” modern phones.

A modern mobile lockscreen is a bit like a house front door that has a decent quality deadbolt lock fitted…

…but also has a letterbox (mail slot), glass panels to let in light, a cat flap, a loidable spring lock that you’ve learned to rely on because the deadbolt is a bit of a hassle, and an external wireless doorbell/security camera that’s easy to steal even though it contains your Wi-Fi password in plaintext and the last 60 minutes of video footage it recorded.

Oh, and, in some cases, even a secure-looking front door will have the keys “hidden” under the doormat anyway, which is pretty much the situation that Schütz found himself in on his Android phone.

A map of twisty passageways

Modern phone lockscreens aren’t so much about locking your phone as restricting your apps to limited modes of operation.

This typically leaves you, and your apps, with lockscreen access to a plentiful array of “special case” features, such as activating the camera without unlokcking, or popping up a curated set of notification mesaages or email subject lines where anyone could see them without the passcode.

What Schütz had come across, in a perfectly unexceptionable sequence of operations, was a fault in what’s known in the jargon as the lockscreen state machine.

A state machine is a sort of graph, or map, of the conditions that a program can be in, along with the legal ways that the program can move from one state to another, such as a network connection switching from “listening” to “connected”, and then from “connected” to “verified”, or a phone screen switching from “locked” either to “unlockable with fingerprint” or to “unlockable but only with a passcode”.

As you can imagine, state machines for complex tasks quickly get complicated themselves, and the map of different legal paths from one state to another can end up full of twists, and turns…

…and, sometimes, exotic secret passageways that no one noticed during testing.

Indeed, Schütz was able to parlay his inadvertent PUK discovery into a generic lockscreen bypass by which anyone who picked up (or stole, or otherwise had brief access to) a locked Android device could trick it into the unlocked state armed with nothing more than a new SIM card of their own and a paper clip.

In case you’re wondering, the paper clip is to eject the SIM already in the phone so that you can insert the new SIM and trick the phone into the “I need to request the PIN for this new SIM for security reasons” state. Schütz admits that when he went to Google’s offices to demonstrate the hack, no one had a proper SIM ejector, so they first tried a needle, with which Schütz managed to stab himself, before succeeding with a borrowed earring. We suspect that poking the needle in point first didn’t work (it’s hard to hit the ejector pin with a tiny point) so he decided to risk using it point outwards while “being really careful”, thus turning a hacking attempt into a literal hack. (We’ve been there, done that, pronged ourselves in the fingertip.)

Gaming the system with a new SIM

Given that the attacker knows both the PIN and the PUK of the new SIM, they can deliberately get the PIN wrong three times and then immediately get the PUK right, thus deliberately forcing the lockscreen state machine into the insecure condition that Schütz discovered accidentally.

With the right timing, Schütz found that he could not only land on the fingerprint unlock page when it wasn’t supposed to appear, but also trick the phone into accepting the successful PUK unlock as a signal to dismiss the fingerprint screen and “validate” the entire unlock process as if he’d typed in the phone’s full lock code.

Unlock bypass!

Unfortunately, much of Schütz’s article describes the length of time that Google took to react to and to fix this vulnerability, even after the company’s own engineers had decided that the bug was indeed repeatable and exploitable.

As Schütz himself put it:

This was the most impactful vulnerability that I have found yet, and it crossed a line for me where I really started to worry about the fix timeline and even just about keeping it as a “secret” myself. I might be overreacting, but I mean not so long ago the FBI was fighting with Apple for almost the same thing.

Disclosure delays

Given Google’s attitude to bug disclosures, with its own Project Zero team notoriously firm about the need to set strict disclosure times and stick to them, you might have expected the company to stick to its 90-days-plus-14-extra-in-special-cases rules.

But, according to Schütz, Google couldn’t manage it in this case.

Apparently, he’d agreed a date in October 2022 by which he planned to disclose the bug publicly, as he’s now done, which seems like plenty of time for a bug he discovered back in June 2022.

But Google missed that October deadline.

The patch for the flaw, designated bug number CVE-2022-20465, finally appeared in Android’s November 2022 security patches, dated 2022-11-05, with Google describing the fix as: “Do not dismiss keyguard after SIM PUK unlock.”

In technical terms, the bug was what’s known a race condition, where the part of the operating system that was watching the PUK entry process to keep track of the “is it safe to unlock the SIM now?” state ended up producing a success signal that trumped the code that was simultaneously keeping track of “is is safe to unlock the entire device?”

Still, Schütz is now significantly richer thanks to Google’s bug bounty payout (his report suggests that he was hoping for $100,000, but he had to settle for $70,000 in the end).

And he did hold off on disclosing the bug after the 15 October 2022 deadline, accepting that discretion is the sometimes better part of valour, saying:

I [was] too scared to actually put out the live bug and since the fix was less than a month away, it was not really worth it anyway. I decided to wait for the fix.

What to do?

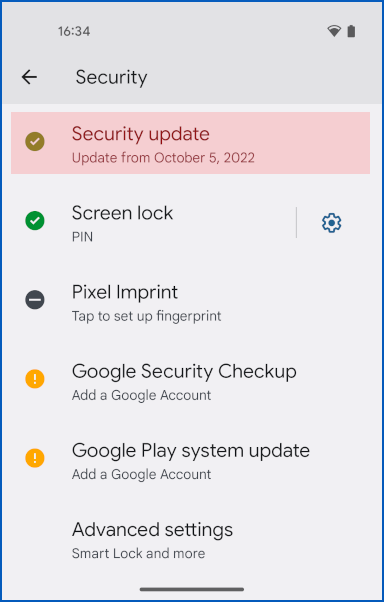

Check that your Android is up to date: Settings > Security > Security update > Check for update.

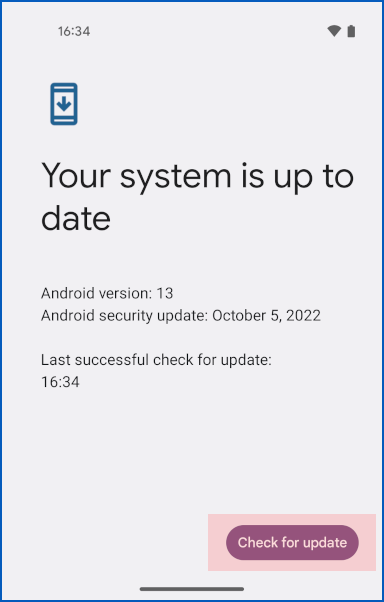

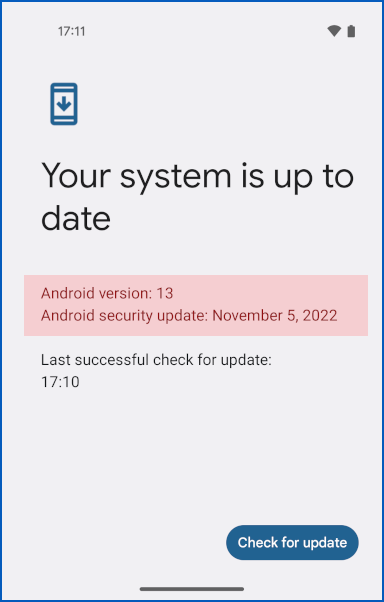

Note that when we visited the Security update screen, having not used our Pixel phone for a while, Android boldly proclaimed Your system is up to date, showing that it had checked automatically a minute or so earlier, but still telling us we were on the October 5, 2022 security update.

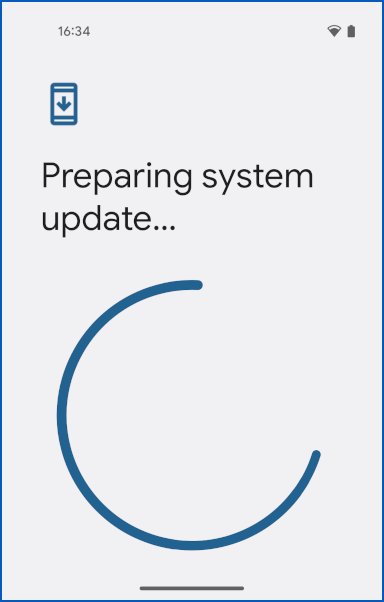

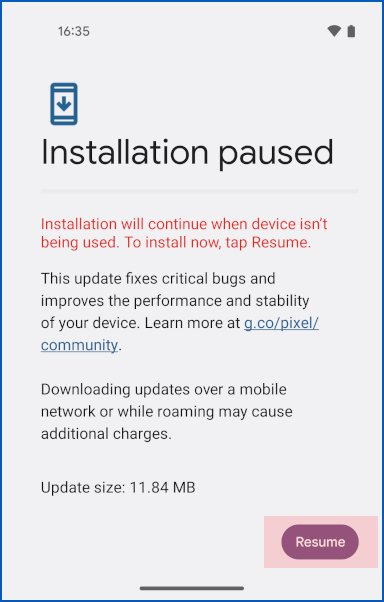

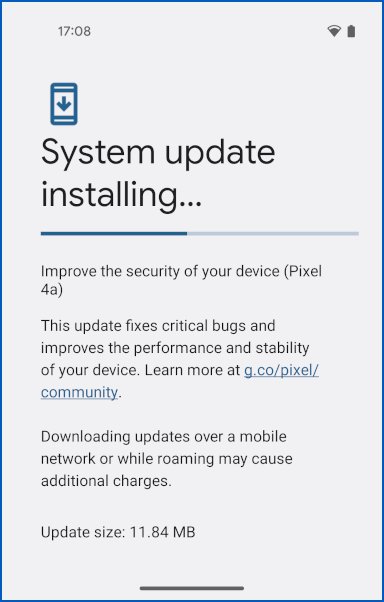

We forced a new update check manually and were immediately told Preparing system update…, followed by a short download, a lengthy preparatory stage, and then a reboot request.

After rebooting we had reached the November 5, 2022 patch level.

We then went back and did one more Check for update to confirm that there were no fixes still outstanding.

We used Settings > Security > Security update to get to the force-a-download page:

The date reported seemed wrong so we forced Android to Check for update anyway:

There was indeed an update to install:

Instead of waiting we used Resume to proceed at once:

A lengthy update process followed:

We did one more Check for update to confirm we were there:

K.G.H. NICHOLES

My Android 8.0 Moto e5 Play says I’m up to date. It’s only a couple of years old – it it already end-of-life?

Paul Ducklin

Did you try forcing an update after it said you were up to date? (I updated the article with some screenshots after your comment appeared, figuring that a pictures is worth 1024 words.)

If there is no update available then there are three possibilities I can think of, and only your phone provider or the Moto vendor can really tell you which one it is: [1] no more updates, thanks for your custom, goodnight [2] update will be coming but isn’t ready yet [3] the latest patches don’t apply to this build/model so you really are are up to date for now.

Sorry I can’t give more solid advice…

Fred

That’s something very nice you explained, so the SIM card actually really fries itself if you enter too many wrong unblocking codes?

That would be a nice storage for sensitive encrypted passwords.

Basically a program could store the sensitive data pre-encrypted in a common SIM card and incase of panic it could immediately close the active session and start instantly sending 3 wrong PINs.

Then it would again try 10 wrong unblocking codes to fry off the SIM card.

The difference between this and normal self-destructive storage is price, and many times you can fetch a free SIM card package without call credits inside.

So, free destructive storage for sensitive data?

For the lockscreen problem I think Android lacks workspaces.

Basically data at rest protection.

Why would one screen unlock let you access everything (even what you don’t need yet)?

Imagine if you could password-protect the /data/data/com.package.name folder of any app by encrypting the files with a different workspace password.

Same problem with VeraCrypt:

If you get caught while the system is running, then you’re dead.

Unless you have data-at-rest protection or strict access boundary rights depending of ‘workspaces’ even when the system is unlocked.

I do know about KNOX, and the native Workspaces of Android but only for Google Pixel phones.

Other phones don’t have many solutions available if any.

Paul Ducklin

The word “fries” was a metaphor, let’s be clear (I don’t think it overvolts itself and literally burns out its circuity, for Health and Safety reasons), but AFAIK the SIM “renders itself inoperable and unrecoverable” after 10 wrong PUKs.

Your mobile phone provider can issue you with a new SIM that answers to the old phone number (thus the problem with crooks doing illegal “number ports” from your SIM card to theirs, thus taking over your number and your calls) but as far as I know, the old SIM is effectively electronic garbage and cannot be reinitialised and re-used at all, let alone have the old data read out of it.

Wilderness

Good find!

Paul Ducklin

Well, the secret’s out now, explicitly because of Schütz’s article, and implicitly because of the notes in Google’s source code fix), so it’s “found” for everyone now.

As Schuetz reminds us all, the bug is in the open source part of Android, not only in Google’s proprietary/commercially licensed Android components, so it almost certainly affects any and all distros based on AOSP, the Android Open Source Project, too.

Jeff Campbell

I like how the article is like to fix this just update your phone. Like the update is available anytime to download. If it’s not available then we can’t just “update” our phone(s). We must wait for the manufacturer to push it out.

Paul Ducklin

I hear you… but please don’t shoot the messenger. I’m not the one who coded the bug in the first place, or who hasn’t got the update ready for you yet…

If you can manage with just Wi-Fi for a while, you could almost certainly sidestep this bug by removing your SIM temporarily, because without a SIM you can never reach the condition where a PIN is requested, let alone entered incorrectly three times…

(I do not recommend removing the PIN code from your SIM as a “workaround”. An unprotected SIM can simply be swapped into a different phone to hijack calls and messages, which is a risk best avoided.)

Steve Clements

VERY interesting article. Many thanks.

P.S. Serenditious?? I think you meant “serendipitous” Just my word OCD!

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks.

(It’s not OCD if you are pointing out a plain and simple error! Although some words freely admit of multiple spellings, shortenings and usages, e.g. jewellery/jewelry, maths/math, expiry/expiration), seren-whateveritis is not one of them :-)

Anonymous

I have tested this bug against a Samsung A71, Android 12, secured by Knox, latest Android security patch of September, 1, it doesn’t work. The lock screen still asks for the password even after having resetted the PIN by using the PUK. It seems it does not impact all Android flavors.

proofreader

Tried to look this up to no avail in case I could learn new vocabulary: loidable

In the article, Shutz (with an umlaut); in the reply to “Good find” is referred to as Shuetz

Paul Ducklin

“Loidable” means “capable of being loided”. Loiding a lock, as far as I know, is a reasonably common expression that means “popping it open by sneaky mechanical means other than by using the key”. For example, using a piece of flat plastic parcel tape round the locking button of a 1990s car to drag it upwards and unlock it; operating the internal mechanical door latch of older cars by shimming a notched hacksaw blade down the outside of the window, thus opening the door while it’s effectively still locked; unlatching a spring lock from the outside or a door with a credit card; shimming a padlock shackle with a strip cut from a beer can so it pops open. (All examples seen on YouTube, folks, just for the avoidance of doubt!)

As for the “ü” character – it’s considered correct German orthography to represent that letter as the ASCII combination “ue” when the “ü” character is inconvenient or unavailable, as in writing Muenchen for München, or Duesseldorf for Düsseldorf. (The -UE- in “Schuetz” is therefore considered one letter when searching or sorting, much like the letters -LL- or -DD- in Welsh, and has its own entry in the dictionary.)

However, for consistency, I have edited the comment so you will see “ü” in both places now.

Christopher Price

Remember how Google said File Based Encryption (FBE) was just as good as Full Disk Encryption (FDE), and then banned FDE from Android?

Pepperidge Farm remembers.

Paul Ducklin

I remember FDE becoming supported, then standard, and finally unavoidable (iPhone style) over the past decade.

I don’t remember it being “banned from Android”.

In fact, flashing Google’s firmware onto my own Pixel phone (e.g. after having an alternative firmware installed) always installs and activates FDE, and from memory there is no option *not* to have it, which feels like exactly the opposite of “banned” to me. (At any rate, there is no official, unrooted way I am aware of to remove FDE and run your device unencrypted.)

If you are referring to a specific incident, a specific time window, a specific region, or a specific version, you should probably explain that – just telling me to “remember” something I simply don’t recall isn’t much help.

Christopher Price

It very much was. Samsung wanted to keep it, as they shared these concerns, but Google prohibited it. Samsung even announced that they were having to remove it from their KNOX security.

Android CDD mandates FBE as the only system wide Android encryption system. Read the CDD, it’s right there.

There was a transitional period where you could upgrade an old OS install, but Google removed that from newer Android CDDs too.

The bottom line is Google killed it, banned it, and gutted it from AOSP. Now it is clear, they should put it back as an optional function.

Paul Ducklin

Yes, I get it now. This sort of makes it clear:

https://source.android.com/docs/security/features/encryption/file-based

So *that’s* what “device encryption” means. Apparently, encrypting files rather than the entire device is so the device can “boot straight to the lock screen” before a passcode is needed.

(Given the many bypass bugs that have shown up in so-called lock screens over the years – because the “lock” in “lock screen” seems to describe a very liberal sort of “lock” to me… always makes me think of a bank vault with a cat flap – I am not sure how this is a feature, for all that it might feel mildly convenient to some people.)

My saving grace is that although I have a Pixel I use it only for research and occasional screenshots for articles – not because of technical concerns, but simply because I just don’t like the UX that much.

Thanks for the clarification. It’s appreciated.