Just over a week ago, the newswires were abuzz with news of a potentially serious bug in the widely-used cryptographic library OpenSSL.

Some headlines went as far as describing the bug as a possibly “worse-than-Heartbleed flaw”, which was dramatic language indeed.

Heartbleed, as you may remember, was a high-profile data leakage bug that lurked unnoticed in OpenSSL for several years before being outed in a flurry of publicity back in 2014:

In fact, Heartbleed can probably be considered a prime early example of what Naked Security jokingly refers to as the BWAIN process, short for Bug With An Impressive Name.

That happens when the finders of a bug aim to maxmise their media coverage by coming up with a PR-friendly name, a logo, a dedicated website, and even, in one memorable case, a theme tune.

Heartbleed was a bug that exposed very many public-facing websites to malicious traffic that said, greatly simplified, “Hey”! Tell me you’re still there by sending back this message: ROGER. By the way, send the text back in a memory buffer that’s 64,000 bytes long.”

Unpatched servers would dutifully reply with something like: ROGER [plus 64000 minus 5 bytes of whatever just happened to follow in memory, perhaps including other people's web requests or even passwords and private keys].

As you can imagine, once news of Heartbleed got out, the bug was easily, quickly and widely abused by criminals and show-off “researchers” alike.

Bad, but not as bad as that

We don’t think these latest bugs reach that level of exploitability or immediate danger…

…but they’re certainly worth patching as soon as you can.

Intriguingly, both bugs fixed in this release are what we referred to in the headline as “one-liners”, meaning that changing or adding just a single line of code patched each of the holes.

In fact, as we’ll see, one of the patches involves changing a single assembler instruction, ultimately resulting in just two swapped bits in the compiled code.

The bugs are as follows:

- CVE-2022-2274: Memory overflow in RSA modular exponentiation. Fortunately, this bug only exists for computers that support Intel’s special AVX512 instruction set, in OpenSSL builds that include special-purpose code for these chips. The programmer was supposed to copy N bits’ worth of

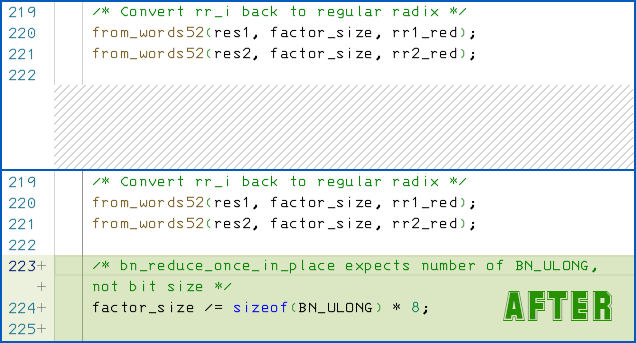

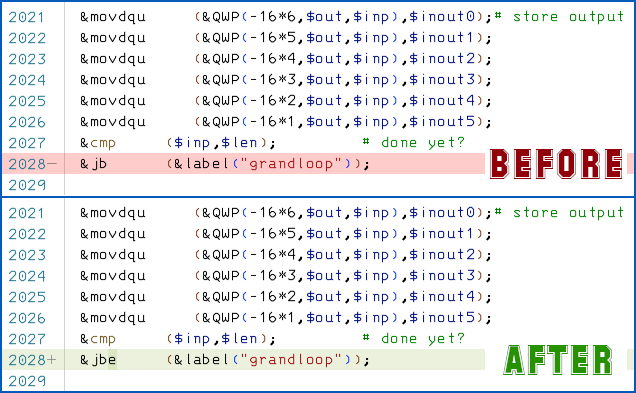

unsigned longintegers (typically 32 or 64 bits each), but inadvertently copied Nunsigned longintegers instead, thus copying far more bits in total than the buffer had space for. The fix was to divide the total number of bits by the bit-size of eachunsigned long, to compute the correct amount of data to copy. - CVE-2022-2097: Data leakage in AES-OCB encryption. When using Intel’s special AES acceleration instructions (widely present on most recent Intel processors), the programmer was supposed to encrypt N blocks of data by running a loop from 1 to N, but inadvertently ran it from 1 to N-1 instead. This means that the last cryptographic block (16 bytes) of an encrypted data buffer could come out with the last block of data still being the original plaintext.

The fixes are simple once you know what’s needed:

The modular exponentiation code now converts a count of bits to a count of integers, by dividing the bit-count by the number of bytes in an integer multiplied by 8 (the number of bits in a byte).

The AES-OCB encryption code now uses a JBE (jump if below or equal to) test at the end of its loop instead of JB (jump if below), which is the same sort of change as altering a C loop to say for (i = 1; i <= n; i++) {...} instead of for (i = 1; i < n; i++) {...}.

In the compiled code, this changes just a single bit of a single byte, namely by switching the binary opcode value 0111 0010 (jump if below) for 0111 0100 (jump if below or equal).

Fortunately, we’re not aware of the special encryption mode AES-OCB being widely used (its modern equivalent is AES-GCM, if you’re familiar with the many AES encryption flavours).

Notably, as the OpenSSL team points out, “OpenSSL does not support OCB based cipher suites for TLS and DTLS,” so the network security of SSL/TLS connections is unaffected by this bug.

What to do?

OpenSSL version 3.0 is affected by both of these bugs, and gets an update from 3.0.4 to 3.0.5.

OpenSSL version 1.1.1 is affected by the AES-OCB plaintext leakage bug, and gets an update from 1.1.1p to 1.1.1q.

Of the two bugs, the modular exponentiation bug is the more severe.

That’s because the buffer overflow means, in theory, that something as fundamental as checking a website’s TLS certificate before accepting a connection could be enough to trigger remote code execution (RCE).

If you are using OpenSSL 3 and you genuinely can’t upgrade your source code, but you can recompile the source you’re already using, then one possible workaround is to rebuild your current OpenSSL using the no-asm configuration setting.

Note that this isn’t recommended by the OpenSSL team, because it removes almost all assembler-accelerated functions from the compiled code, which may therefore end up noticeably slower, but it will eliminate the unwanted AVX512 instructions entirely.

To suppress the offending AES-OCB code alone, you can recompile with the configuration setting no-ocb, which ought to be a harmless intervention if you aren’t knowingly using OCB mode in your own software.

But the best solution is, as always: Patch early, patch often!

Larry Marks

0111 0100 XOR 0111 0010 = 0000 0110. That is, to patch the binary instruction (or assembler opcode), you must change TWO bits, not one,

Paul Ducklin

Errr, yes. I just saw it as one bit that moved one bit… I guess I can say “swap two bits” instead.

Vivek

Re “The programmer was supposed to copy N unsigned long integers (typically 32 or 64 bits each), but inadvertently copied N bits instead.”: I think it should be the other way around: the previous buggy code inadvertently copied N unsigned long integers (typically 32 or 64 bits each), but was supposed to copy only N bits. It overwrote (way) more than it was supposed to, causing the overflow.

Paul Ducklin

Yes, I knew what I meant but I didn’t write it down that way! I have reworded it so I think it now clearly indicates what happened: instead of copying N bits’ worth of unsigned longs, they copied N unsigned longs instead. So the fix was to convert “count of bits” to “equivalent count of unsigned longs”.

Thanks for the comment.