We’ll tell this story primarily through the medium of images, because a picture is worth 1024 words.

This cybercrime is a visual reminder of three things:

- It’s easy to fall for a phishing scam if you’re in a hurry.

- Cybercriminals don’t waste any time getting new scams going.

- 2FA isn’t a cybersecurity panacea, so you still need your wits about you.

It was 19 minutes past…

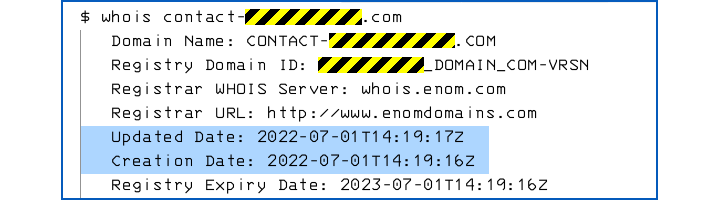

At 19 minutes after 3 o’clock UK time today [2022-07-01T14:19:00.00Z], the criminals behind this scam registered a generic and unexceptionable domain name of the form contact-XXXXX.com, where XXXXX was a random-looking string of digits, looking like a sequence number or a server ID:

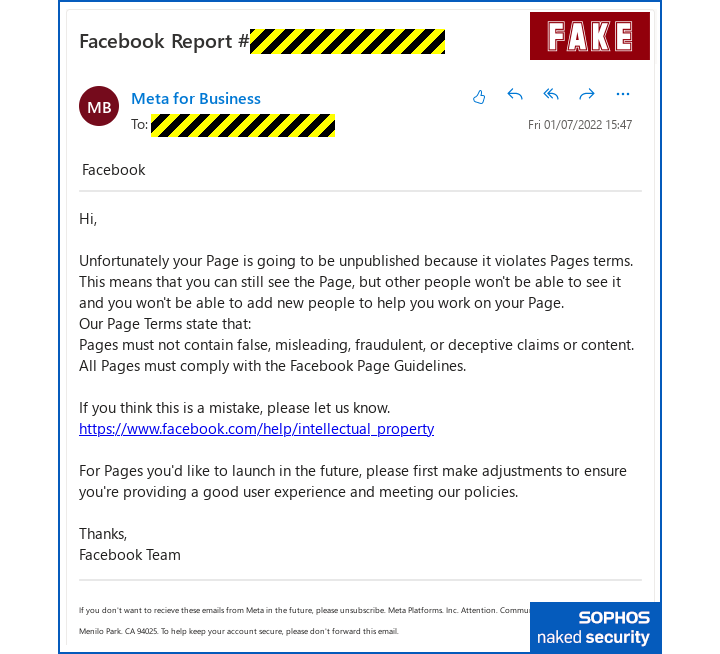

28 minutes later, at 15:47 UK time, we received an email, linking to a server called facebook.contact-XXXXX.com, telling us that there might be a problem with one of the Facebook Pages we look after:

As you can see, the link in the email, highlighted in blue by our Oulook email client, appears to go directly and correctly to the facebook.com domain.

But that email isn’t a plaintext email, and that link isn’t a plaintext string that directly represents a URL.

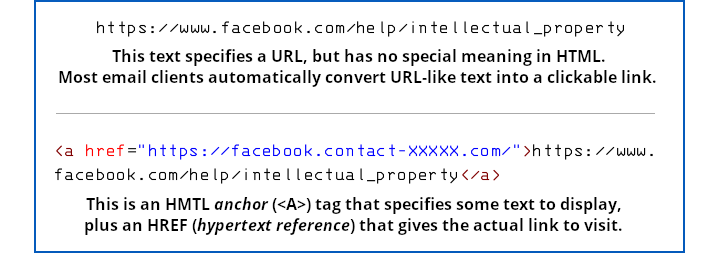

Instead, it’s an HTML email containing an HTML link where the text of the link looks like a URL, but where the actual link (known as an href, short for hypertext reference) goes off to the crook’s imposter page:

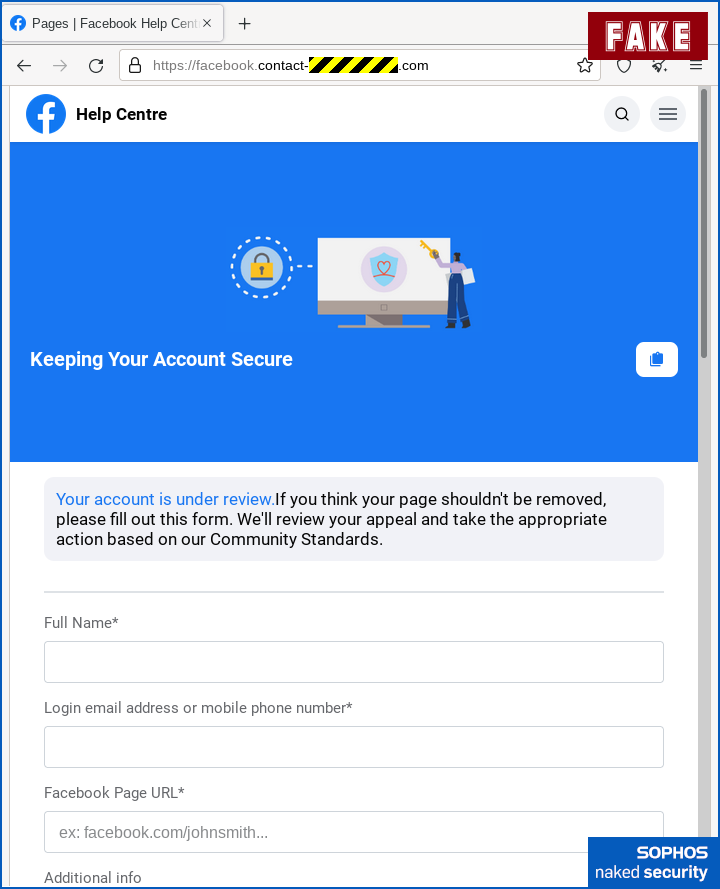

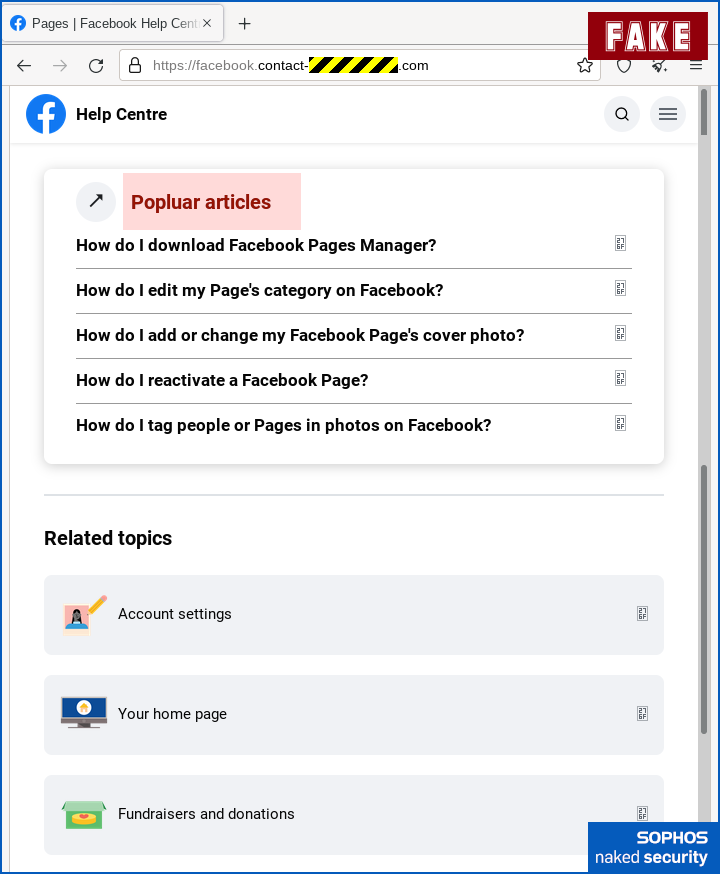

As a result, clicking on a link that looked like a Facebook URL took us to the scammer’s bogus site instead:

Apart from the incorrect URL, which is disguised by the fact that it starts with the text facebook.contact, so it might pass muster if you’re in a hurry, there aren’t any obvious spelling or grammatical errors here.

Facebook’s experience and attention to detail means that the company probably wouldn’t have left out the space before the words “If you think”, and wouldn’t have used the unusual text ex to abbreviate the word “example”.

But we’re willing to bet that some of you might not have noticed those glitches anyway, if we hadn’t mentioned them here.

If you were to scroll down (or had more space than we did for the screenshots), you might have spotted a typo further along, in the content that the crooks added to try to make the page look helpful.

Or you might not – we highlighted the spelling mistake to help you find it:

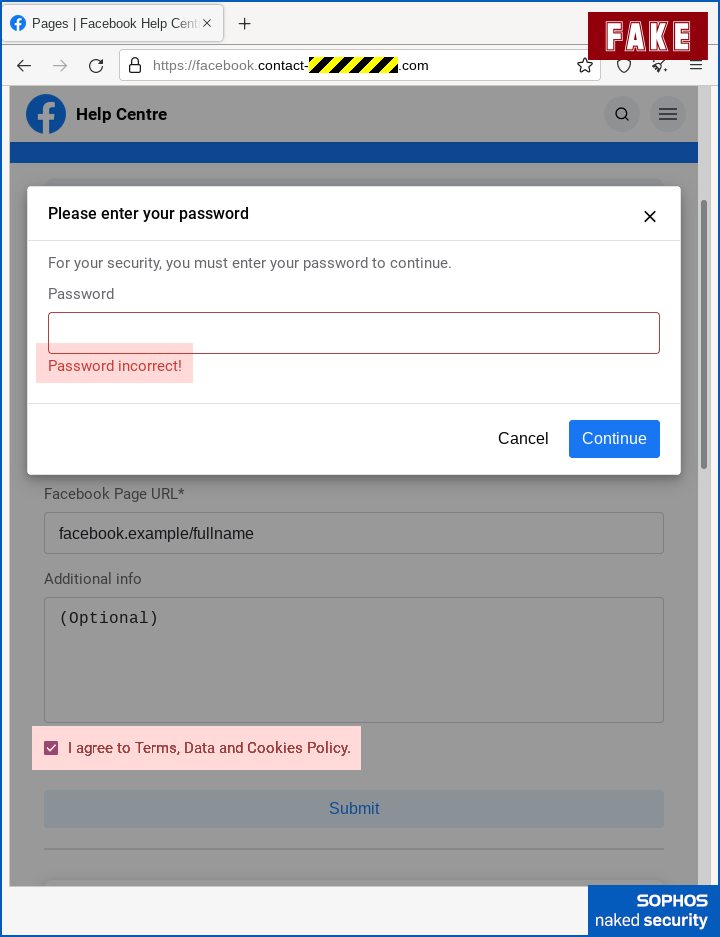

Next, the crooks asked for our password, which wouldn’t usually be part of this sort of website workflow, but asking us to authenticate isn’t totally unreasonable:

We’ve highlighted the error message “Password incorrect”, which comes up whatever you type in, followed by a repeat of the password page, which then accepts whatever you type in.

This is a common trick used these days, and we assume it’s because there’s a tired old piece of cybersecurity advice still knocking around that says, “Deliberately put in the wrong password first time, which will instantly expose scam sites because they don’t know your real password and therefore they’ll be forced to accept the fake one.”

To be clear, this has NEVER been good advice, not least when you’re in a hurry, because it’s easy to type in a “wrong” password that is needlessly similar to your real one, such as replacing pa55word! with a string such as pa55pass! instead of thinking up some unrelated stuff such as 2dqRRpe9b.

Also, as this simple trick makes clear, if your “precaution” involves watching out for apparent failure followed by apparent success, the crooks have just trivially lulled you into into a false sense of security.

We also highlighted that the crooks also deliberately added a slightly annoying consent checkbox, just to give the experience a veneer of official formality.

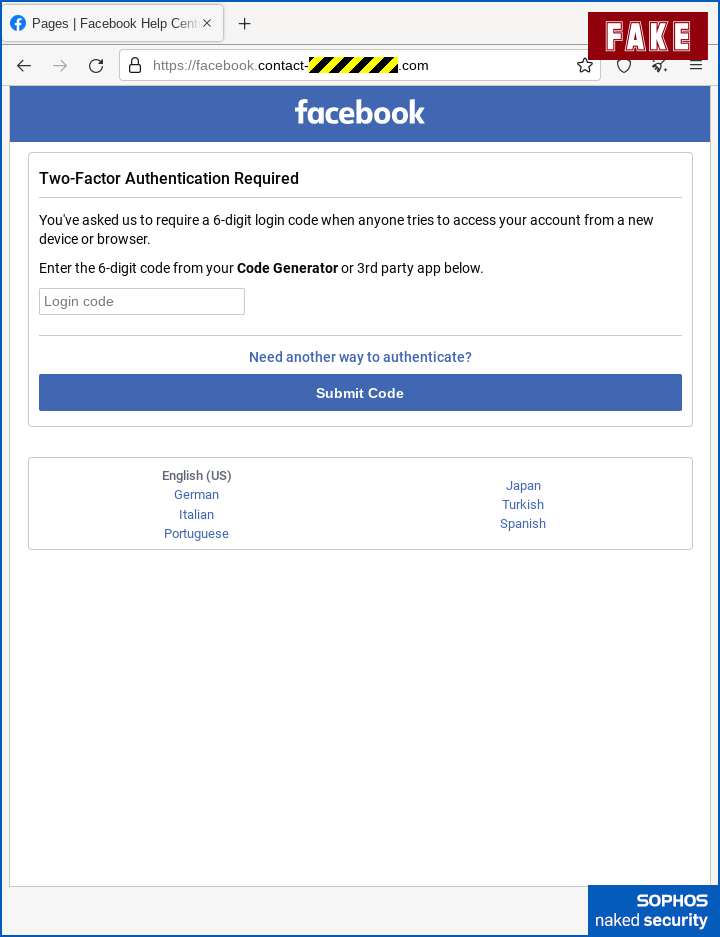

Now you’ve handed the crooks your account name and password…

…they immediately ask for the 2FA code displayed by your authenticator app, which theoretically gives the criminals anywhere between 30 seconds and a few minutes to use the one-time code in a fraudulent Facebook login attempt of their own:

Even if you don’t use an authenticator app, but prefer to receive 2FA codes via text messages, the crooks can provoke an SMS to your phone simply by starting to login with your password and then clicking the button to send you a code.

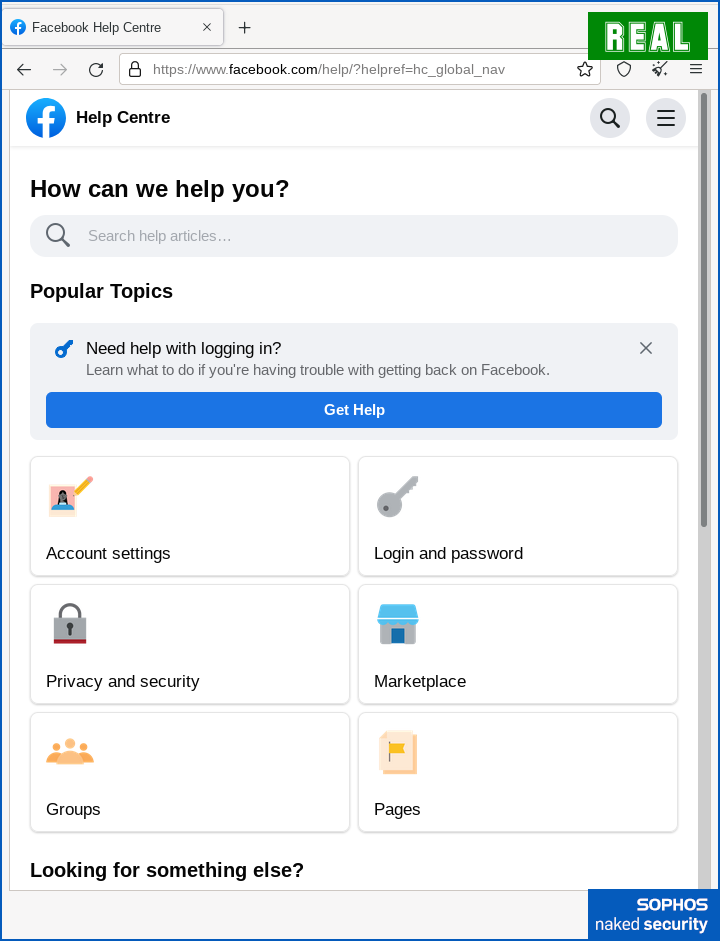

Finally, in another common trick these days, the criminals soften the dismount, as it were, by casually redirecting you to a legitimate Faceook page at the end.

This gives the impression that the process finished without any problems to worry about:

What to do?

Don’t fall for scams like this.

- Don’t use links in emails to reach official “appeal” pages on social media sites. Learn where to go yourself, and keep a local record (on paper or in your bookmarks), so that you never need to use email web links, whether they’re genuine or not.

- Check email URLs carefully. A link with text that itself looks like a URL isn’t necessarily the URL that the link directs you to. To find the true destination link, hover over the link with your mouse (or touch-and-hold the link on your mobile phone).

- Check website domain names carefully. Every character matters, and the business part of any server name is at the end (the right-hand side in European languages that go from left-to-right), not at the beginning. If I own the domain

dodgy.examplethen I can put any brand name I like at the start, such asvisa.dodgy.exampleorwhitehouse.gov.dodgy.example. Those are simply subdomains of my fraudulent domain, and just as untrustworthy as any other part ofdodgy.example. - If the domain name isn’t clearly visible on your mobile phone, consider waiting until you can use a regular desktop browser, which typically has a lot more screen space to reveal the true location of a URL.

- Consider a password manager. Password managers associate usernames and login passwords with specific services and URLs. If you end up on an imposter site, no matter how convincing it looks, your password manager won’t be fooled because it recognises the site by its URL, not by its appearance.

- Don’t be in a hurry to put in your 2FA code. Use the disruption in your workflow (e.g. the fact that you need to unlock your phone to access the code generator app) as a reason to check that URL a second time, just to be sure, to be sure.

Remember that phishing crooks move really fast these days in order to milk new domain names as quickly as they can.

Fight back against their haste by taking your time.

Remember those two handy sayings: Stop. Think. Connect.

And after you’ve stopped and thought: If in doubt, don’t give it out.

ElbowNi

Why would a scammer go to the bother of creating a fake page when EvilGnx will just proxy the real page and automatically steal the MFA cookie? No typos, no grammatical issues, and as its a proxy it will only accept the correct credentials.

Paul Ducklin

Setting up a proxy for a facebook.com domain would require you to have a web certificate [a] that claims to be Facebook’s and [b] that the user’s browser will accept.

The first part (making the fake certificate) is easy. The second part (getting the fake certificate digitally signed by a trusted authority) is hard.

Thus the crooks use fake sites instead, based on domain names for which they can acquire signed certificates.

Franky

“Setting up a proxy for a facebook.com domain would require you to have a web certificate [a] that claims to be Facebook’s and [b] that the user’s browser will accept.”

Actually not so, if you look at how EvilGinx2 works (on Github) as mitm proxy, it requires the attacker to setup a look-like domain to front the victim for which he will obtain Let’sEncrypt certificate). Attacker does not need to obtain facebook.com certificate nor need to trick users browser to trust that certificat.

Going back to the original question from ElbowNi, I think Evilginx2 is whole new advanced level of phishing attack that “ordinary” attacker has not aquired their skills to use yet.

Paul Ducklin

Perhaps I should have been more precise and said “setting up an invisible proxy”, or “setting up a true MiTM proxy that presents itself as facebook.com”.

Evilgnx (which used nginx) and Evilgnx2 (which is self-contained) would still present itself in the same way as this scam did, using a URL pointing at a domain that is *not* facebook.com, with an HTTPS certificate that was not issued to facebook.com. (Most phishing scams these days use HTTPS. Either they use Let’s Encrypt, like Evilgnx does if you want it to, or they use a cheap hosting service that provides domain+certificate+web server that’s ready to go.)

This is the point that @jeret made. The phishing attempt would still require a fake domain name, just as you see here, which is visible to the victim. The Evilgnx proxy doesn’t act as a full MiTM proxy like (say) a web filtering firewall, which generates fake certificates for the domains that it proxies, and therefore requires the user to trust a non-standard certificate authority first.

I take the point of the OP that Evilgnx2 effectively fetches the “fake pages” on demand, which avoids typos and so on…

…but I suspect that one reason the crooks tend to use their own fake site content is that it makes it easy for them to build their own non-standard workflow to lure you to a fake password prompt in the first place.

jeret

Well, with evilginx you still need a domain registered. You can easily identify the page by just looking at the spoofed domain!

Laurence Marks

Text refers to “control=XXXXX” in two places. The images all display “contact-XXXXX”.

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks!