On January 24, 2022, we published an article on the trends Sophos was seeing related to people scanning and attacking the Log4Shell vulnerability in Apache Log4J software, as observed by Sophos Firewall customers.

In response, a reader on Twitter, @DrewHjelm, inquired about the distribution of scans between hosting providers and suspicious hosts. This was a very insightful question, so I decided to see if I had the information to answer Drew’s question.

The data I’ve used is a sample based on customers that participate in Sophos telemetry, and this number can vary over time. It is still very useful, however. I used percentages to look at the source autonomous system numbers (ASNs) of scans and attack attempts, and both the December 2021 and January 2022 datasets are large enough to paint a rather interesting picture.

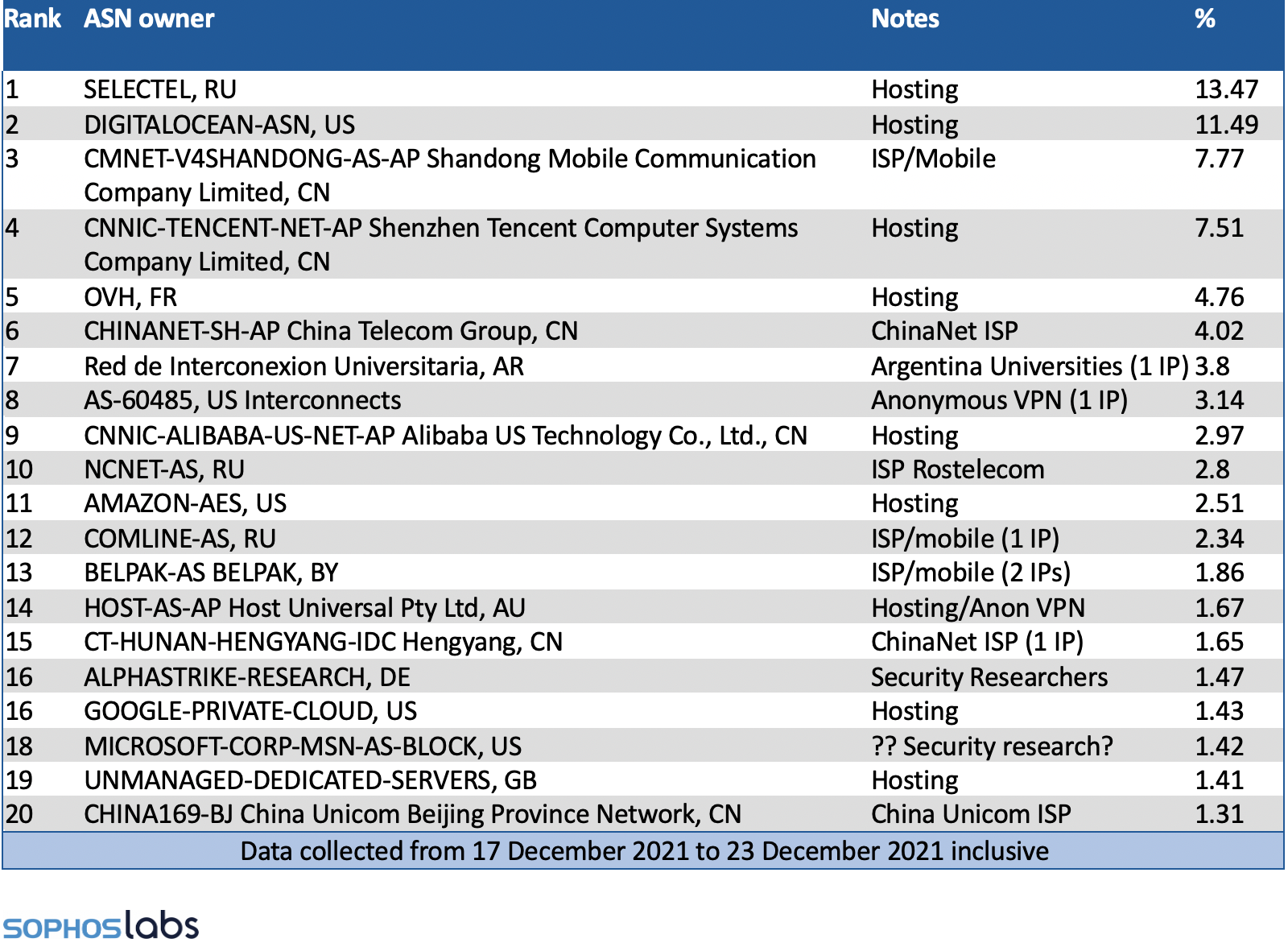

I looked at two weeks in particular. The first dataset is from December 17, 2021, to December 23, 2021, and looks into who was scanning during the peak of attacks in the weeks following the bug’s discovery. The second dataset covers January 19, 2022, to January 25, 2022, which is approximately one month later and the most current data I had at hand when I began the task.

There has been much speculation about who is generating all this traffic. The Apache Log4J software tool is so widely deployed, in so many products and services, that both criminals and nation-state attackers would be foolish to pass up the chance to potentially secure a foothold inside an organization that has it installed somewhere. Security researchers have also been scanning at volume to assess the risk of those attackers succeeding and to monitor the progress of patching the flaws.

We have also seen a limited number of more wide-scale automated attacks targeting VMware Horizon and IoT devices by Mirai and other botnets. Security Researcher Dr. Vesselin Bontchev responded to our original post on Twitter, noting he was mostly observing scanners and botnets attacking his network.

Scanning Sources in December 2021

So, what’s in the data? Well, that busy week in December, with a limited number of firewalls sharing telemetry, we observed 1,497 unique IP addresses originating from 234 unique ASNs scanning and attacking over seven days. The top 20 ASNs are noted in the table by percentage of traffic generated. This dataset has a very long tail.

With very few exceptions, the top 20 are mostly hosting, VPS, or cloud providers. In my experience, this represents a mélange of penetration testers, cybercriminals and nation states. The remaining few are either security researchers or IPs known to host anonymous VPNs, demonstrating that the early wave was ultimately a land rush of information gathering and expedient exploitation before many had the opportunity to assess and patch their vulnerability.

The Scanning Sources in January 2022

Now we can look at the second data set. This data was collected from January 19, 2022, until January 25, 2022, and includes a higher number of firewalls. As noted previously, this shouldn’t alter the percentages as much as the raw volume.

Despite the large increase in volume of telemetry it contains only 268 unique IP addresses (compared to 1,497 in December) from 93 ASNs (234 in December). This is a dramatic shift in operations, from the free for all we observed leading up to the Christmas holidays to a far more select groups of scanners and attackers.

As a security researcher these differences are very interesting. First off, the landscape shifted significantly toward security research that is identifiable and known anonymous VPN or questionable bulletproof hosting services.

The End of Amateur Hour?

My impression from this is that the amateurs and the less skilled criminals have moved on to shinier and more interesting endeavors. What’s left? A noisy relentless cohort of potentially dangerous attackers combined with over-eager security researchers creating just enough noise to make it hard for SOCs and red teamers to find the signal.

Additionally, the tail is MUCH shorter even though this a much larger dataset. We have likely reached a point where the types of probes being sent by security researchers and bots like Mirai can be sifted and sorted out of the alerts using YARA rules, to begin identifying genuine attempts at hands-on-keyboard exploitation.

As I stated before, this software is embedded in way too many systems for it not to be a darling for penetration testers and cybercriminals for many years to come. Now that activity has died down, we can begin to refine our defenses and alerts to hunt down the truly dangerous ones.

What we must not forget is that unprotected and unpatched systems internal to our networks provide opportunities for privilege escalation and remote code execution, even if “remote” means another internal system someone gained a foothold on. Organizations that have eliminated the risk from internet facing systems now need to apply the same scrutiny internally to ensure this isn’t their future undoing.

The threat has shifted, but it has not vanished.

Leave a Reply