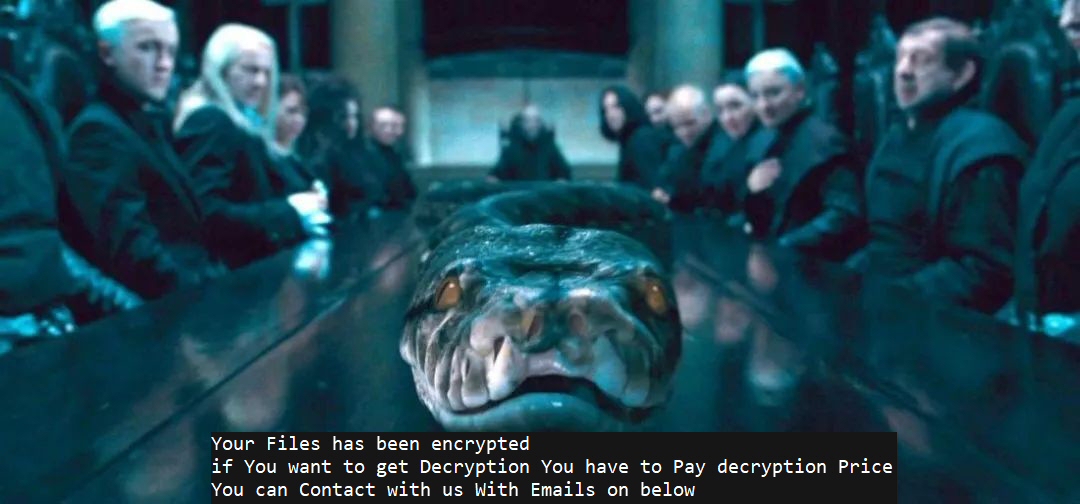

A recently-concluded investigation into a ransomware attack revealed that the attackers executed a custom Python script on the target’s virtual machine hypervisor to encrypt all the virtual disks, taking the organization’s VMs offline.

In what was one of the quickest attacks Sophos has investigated, from the time of the initial compromise until the deployment of the ransomware script, the attackers only spent just over three hours on the target’s network before encrypting the virtual disks in a VMware ESXi server.

The attackers initially accessed their foothold by logging in to a TeamViewer account (one which didn’t have multi-factor authentication set up), running in the background on a computer that belongs to a user with Domain Administrator credentials in the target’s network. The attackers logged on at 30 minutes past midnight in the target organization’s time zone, and ten minutes later downloaded and ran a tool called Advanced IP Scanner to identify targets on the network.

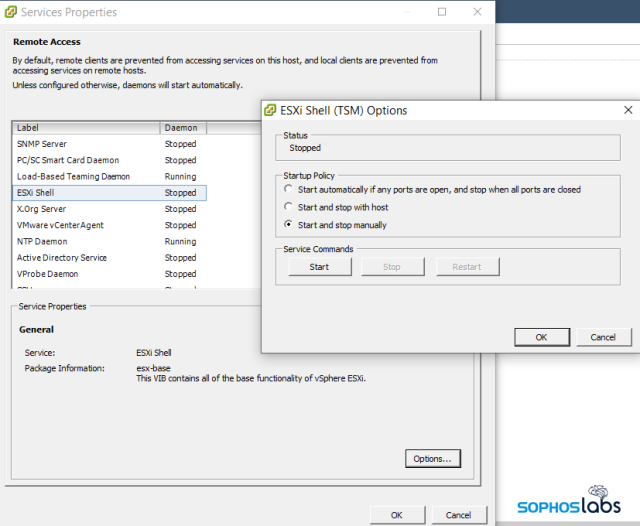

Just before 2 am, the attackers downloaded an SSH client called Bitvise, and used it to log into a VMware ESXi server they identified using Advanced IP Scanner. ESXi servers have a built-in SSH service called the ESXi Shell that administrators can enable, but is normally disabled by default.

This organization’s IT staff was accustomed to using the ESXi Shell to manage the server, and had enabled and disabled the shell multiple times in the month prior to the attack. However, the last time they enabled the shell, they failed to disable it afterwards. The criminals took advantage of this fortuitous situation when they found the shell was active.

Python ransomware

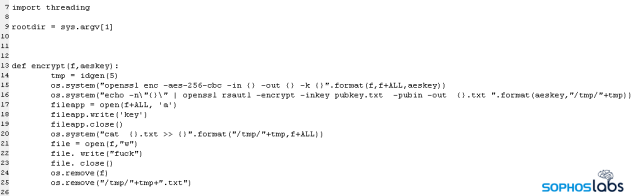

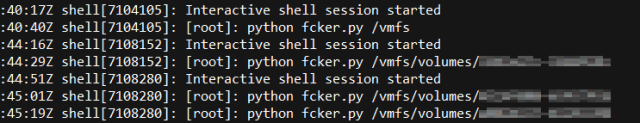

Three hours after the attackers scanned the network, they used their credentials to log into the ESXi Shell, and copied a file named fcker.py to the ESXi datastore, which houses the virtual disk images used by the VMs that run on the hypervisor.

One by one, the attackers executed the Python script, passing the path to datastore disk volumes as an argument to the script. Each individual volume contained the virtual disk and VM settings files for multiple virtual machines.

Thanks to some solid forensics work, the Rapid Response team recovered a copy of the Python script, even though the attackers appeared to have overwritten it with other data before deleting the file.

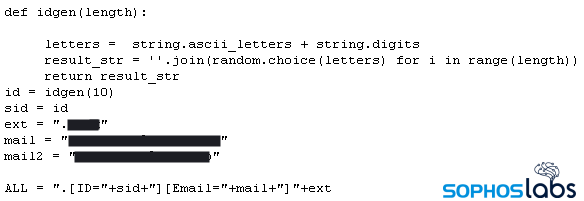

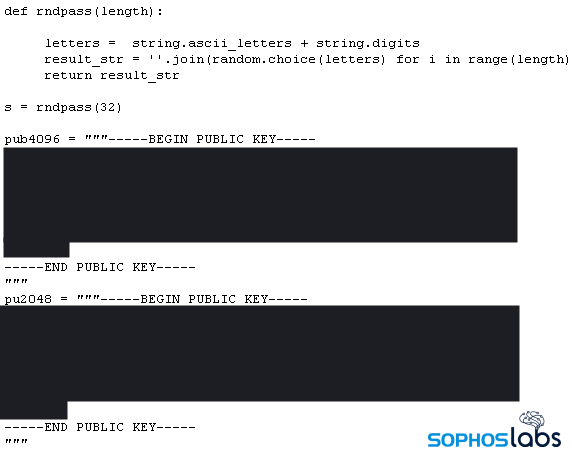

Only 6kb long, the small size of the script belies its abilities. The script contains variables that the attacker can configure with multiple encryption keys, email addresses, and where they can customize the file suffix that gets appended to encrypted files.

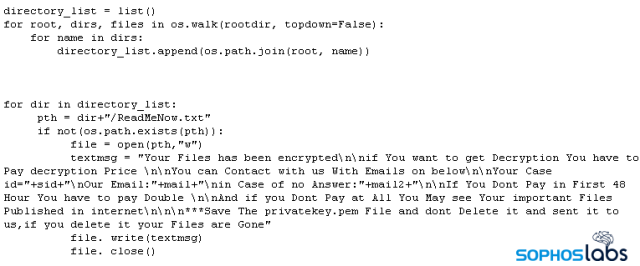

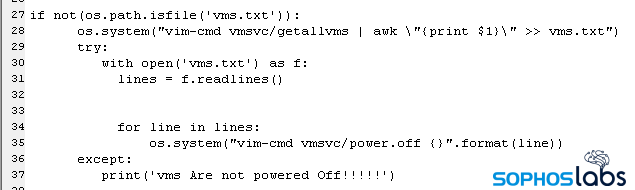

Initially, the script “walks” the filesystem of a datastore and creates a directory map of the drive, and inventories the names of every virtual machine on the hypervisor, writing them to a file called vms.txt. It then executes the ESXi Shell command vim-cmd vmsvc/power.off, one time for each VM, passing the VM names to the command as a variable, one at a time. Only when the VMs have powered off will the script begin encrypting the datastore volumes.

Using a single instruction for each file it encrypts, the script invokes the open-source tool openssl to encrypt the files with the following command:

openssl rsautil -encrypt -inkey pubkey.txt -pubin -out [filename].txt

The script then overwrites the contents of the original file with just the word fuck then deletes the original file. Finally, it deletes the files that contain the directory listings, the names of the VMs, and itself by overwriting those files before deleting them.

Encryption keys generated on-the-fly

One thing that we noticed while walking through the code was the presence of multiple, hardcoded encryption keys, as well as a routine for generating even more encryption key pairs. Normally, an attacker would only need to embed the “public key” that the attacker generated on their own machine and would be used to encrypt files on the targeted computer(s). But this ransomware appears to create a unique key every time it is run.

So what’s going on with that?

Apparently, every time the malware is executed – and it appears the attackers executed the script once for each ESXi datastore they wanted to encrypt – the ransomware generates a unique key pair that will be used for encrypting files during that particular execution.In the case of the attack we investigated, there were three datastores the attackers targeted with individual executions of the script, so the script created three unique key pairs, one for each datastore.

The script has no ability to transmit these keys anywhere, and there’s no way for the attacker to predict what the keys will be, so the script has to leave behind a copy of the secret key (the key the attacker would need in order to decrypt the files) on the filesystem of the targeted computer. But it would be a gigantic mistake to just leave that key lying around (whoever possesses the secret key could, theoretically, use it to decrypt everything without having to pay a ransom), so the script writes out a copy of that secret key, and then encrypts the secret key using the embedded, hardcoded public key.

The script runs a routine that lists all the files in the path that’s provided to the script during execution. For each file, the script generates a unique, 32-byte random code it calls the aeskey, and then encrypts the file using the aeskey as a salt into the /tmp path.

Finally, it prepends the aeskey value to the encrypted file and appends a new file suffix to the name, overwrites the contents of the original file with the word fuck then deletes the original file, and moves the encrypted version from /tmp to the datastore location where the original file was stored.

Hypervisors are valuable targets

Malware that runs under a Linux-like operating system such as ESXi uses is still relatively uncommon, but it is even less common for IT staff to install endpoint protection on servers like these. Hypervisors in general are often quite attractive targets for this kind of attack, since the VMs they host may run business-critical services or functions.

Administrators who operate ESXi or other hypervisors on their networks should follow security best practices, avoiding password reuse, and using complex, difficult to brute-force passwords of adequate length. Wherever possible, enable the use of multi-factor authentication and enforce the use of MFA for accounts with high permissions, such as domain administrators.

In the case of ESXi, use of the ESXi Shell is something that can be toggled on or off from either a physical console at the machine itself, or through the normal management tools provided by VMware. Administrators should only allow the Shell to be active during use by staff, and should disable it as soon as maintenance (such as the installation of patches) is complete.

VMware has also published a list of best practices for administrators of their ESXi hypervisors on how to secure them and limit the attack surface on the hypervisor itself.

Python scripts of this type are detected by Sophos endpoint products as Troj/Ransom-GJR.

Acknowledgments

SophosLabs wishes to acknowledge the work of Rajesh Nataraj, Andrew O’Donnell, and Mauricio Valdivieso for their assistance

VALENTIN MANUKHIN

Running TeamViewer on a PC in non-admin network, with tcp 22 access to virtualization host, and with D admin account logged in. They totally deserved it. That’s freaking insane in terms of information security.

All IT personnel should be punished real hard.

bharat ghelani

good one but there is a technical catch….you are referring to esxi shell but remote login needs ssh service…I think there is a mix up in the article

Andrew Brandt

They were able to access the management UI via the compromised PC. SSH service might have been previously enabled in a timeframe that exceeded the content of the available logs on the hypervisor, just like the ESXi Shell had been enabled a few weeks earlier and left on.

Joe

This attack is a classic Swiss cheese effect. The attackers obviously had access to the network and so security had failed in multiple ways. The aim of the game should be multiple lines of defence to thwart would be attackers.

Joe Shmoe

Great article!

However, you didn’t explain how did they login to the ESXI Shell, do you mean that they used the vCenter? (based on the screenshot, it looks like the Windows native old vCenter), cause ESXI shell request a password and it doesn’t have some “auto login”…

Andrew Brandt

The compromised PC belonged to an admin, who left their password manager open in a browser tab on their desktop. The password manager contained credentials for the root account on the ESXi server.

AK

If root password was saved in the browser then attacker could enable ssh.

Vishnu

Great one Andrew and team!

Thought the password manager would have auto locked (unless the admin is super lazy and disabled it) but it appears attackers were in the network for a prolonged time to watch admin in action before attacking?

LEM

Great catch! Thanks for the detailed information. I appreciate it much. BTW, do we have IoC for this?

Raven

The attackers were patient with this one, it is as simple as that, they did all the recon & all the they had to do was wait for the opportune time. All they did was observe & record & wait for the opportunity to use collected intelligence.