You’ve probably heard of Let’s Encrypt, an organisation that makes it easy and cheap (in fact, free) to get HTTPS certificates for your web servers.

HTTPS, short for secure HTTP, relies on the encryption protocol known as TLS, which is short for transport layer security.

TLS encrypts and protects the data you send back and forth during a network session so that it can’t easily be snooped on in transit, and so it can’t sneakily be altered along the way.

Because of these features, protecting both the confidentiality of your browsing and the integrity of the data you download, most of us agree these days that HTTPS is vitally important when we use the web.

Even if the data you’re looking at is neither private nor secret, crooks can learn a lot about you by keeping an eye on your interests, so why make it easy for them learn to more than they need to know?

Likewise, if you’re downloading a report (or an app) from a site you trust, why make it easy for cybercriminals to switch out your download along the way with a fake news document (or to poke malware-laden content into the middle of an otherwise harmless program)?

Why not use simply use HTTPS for everything, just in case, in the same way that you wear your seatbelt every time you travel in a car, instead of using it only when you think road conditions are at their most dangerous?

When HTTPS “was a hassle”

If you go back a decade or so, HTTPS was not universally or even widely used, and there were two main reasons:

- TLS certificates were a hassle to acquire and use, and cost money. Sites such as charities, hobbyists and small businesses resented having to pay what they saw as a “web tax”, especially given that certificates need renewing regularly.

- TLS network connections were slower than unencrypted ones. Many high-traffic sites were afraid of HTTPS because of the extra time taken by the “cryptographic dance” demanded by the protocol every time a visitor arrived at the site, and because of the need to encrypt and decrypt every byte sent and received thereafter.

Indeed, until about 2010, our attitudes to HTTPS were much more lax than today, to the point that even mainstream websites such as social media, webmail and online shopping only bothered with TLS at so-called “critical moments”.

Before 2010, the page at the start of a browsing session that asked for your password, for example, might use HTTPS (on well-known websites, at any rate), to prevent your password being sniffed out.

Likewise, the page that took your credit card details at the end would probably (though sadly not always) be encrypted, too.

But the vast bulk of your browsing would skip HTTPS altogether, because a snappy browsing experience was considered much more important than a secure one.

This minimalist approach to online security so that it protected only “truly personal” data such as passwords and payment card details was widely considered satisfactory at the time.

Following the sheep

If high-traffic, big-name sites could get away with using HTTPS only some of the time, it was unsurprising that many other sites followed suit, or didn’t bother with HTTPS at all.

In 2010, however, our collective attitude suddenly changed, in no small part due to a Firefox plugin called Firesheep.

This provocative toolkit was created in the hope of convincing us not to be a bunch of sheep, and not blindly to follow the crowd in accepting unencrypted web content as an unavoidable necessity.

With Firesheep, anyone who felt like having a go at being a network hacker could sit in a coffee shop, open up an innocent looking Firefox browsing session, and let the plugin monitor all the unencrypted traffic on the network.

Firesheep’s goal was to watch out for data going to and from other users on the network who had already completed their “secure” login to a site such as Facebook or Twitter.

Those unencrypted network packets didn’t reveal the user’s actual password, but they did expose the current authentication token, or secret session cookie, that was added to each request to prove that this user had already logged in.

Firesheep would automatically slurp up these authentication tokens and inject them into fake Facebook and Twitter traffic in order to compromise other people’s accounts.

By this means, a wannabe attacker – who could already read your posts anyway, even if they were not intended for public broadcast, because they were not using HTTPS – could subvert your account by making posts in your name.

Directly from the click-to-hack simplicity of a browser window.

The cost of security

This dramatic reminder that we ought to be using web encryption all the time, not just some of the time, resulted in increasingly strident calls for “HTTPS everywhere”.

(Naked Security’s contribution to the early debate was an open letter to Facebook, penned back in 2011; similar pressure from voices across the internet gradually led to networking giants such as Facebook, Microsoft and Google adopting HTTPS for everything.)

Indeed, those early adopters of “HTTPS for everything” showed that on modern computing hardware, the computational overhead imposed by TLS was much less dramatic than many people had feared…

…but this didn’t solve the problem of cost, notably for websites run by enthusiasts and small businesses.

Each server certificate you needed might cost $100 a year, and you had to make sure you didn’t forget to renew the certificates in time, or else your visitors would start getting scary looking “untrusted site – certificate has expired” warnings every time.

Why the cost?

Creating your own TLS certificates, as it happens, takes seconds and can be done for free.

For example, these OpenSSL commands will generate a public/private keypair in the file key.pem, and then create a TLS certificate for the website naksec.test, signed with the newly created private key:

# Generate new Edwards-448 keypair into key.pem

$ openssl genpkey -algorithm ED448 -out key.pem

# Self-sign webcert for CN (certificate name) 'naksec.test' into cert.pem

$ openssl req -x509 -key key.pem -subj '/CN=naksec.test' -days 1 -out cert.pem

# Print out details of new certificate in text format

$ openssl x509 -in cert.pem -noout -text

Certificate:

Data:

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number: [. . .]

Signature Algorithm: ED448

Issuer: CN = naksec.test

Validity

Not Before: Sep 28 17:14:31 2021 GMT

Not After : Sep 29 17:14:31 2021 GMT

Subject: CN = naksec.test

Subject Public Key Info:

Public Key Algorithm: ED448

ED448 Public-Key: [. . .]

X509v3 extensions:

X509v3 Subject Key Identifier: [. . .]

X509v3 Authority Key Identifier: [. . .]

X509v3 Basic Constraints: critical

CA:TRUE

Signature Algorithm: ED448

[. . .]

$

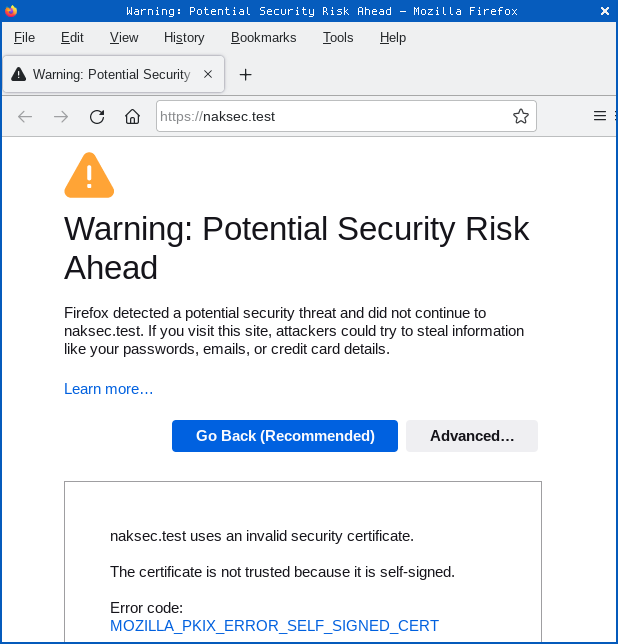

The problem is that a self-signed key (in the example above, the matching Subject and Issuer fields make it clear that we signed this key ourselves) won’t get you very far if you want to run a webserver in the real world.

You need to get someone (an organisation known as a CA, short for certificate authority) to carry out at least a basic check that you actually operate the website you’re claiming to represent, and then to sign your certificate in order to vouch for you.

And you need to use a CA that is already trusted by the vast majority of browsers out there, so that your newly signed certificate will automatically work unimpeded for the vast majority of users.

Otherwise your visitors would be confronted with scary looking “Attackers might be trying to steal your information” or “Warning: potential security risk ahead” messages every time.

Certificates for free

Started back in 2014, a non-profit organisation called Let’s Encrypt set out to change the HTTPS landscape not only by acting as a CA that offered TLS certificates for free, but also by automating and therefore greatly simplifying the process of acquiring and renewing them.

(Let’s Encrypt wasn’t the first project to do free certificates, but it has been one of the most successful at making its free certificates widely accepted and easy to use.)

The only slightly unusual thing about Let’s Encrypt certificates at the outset was that it couldn’t easily act as a CA to itself, given that it was brand new, making it tricky to gain interest and acceptance.

Most HTTPS certificates have a “chain of trust” three links long:

- The certificate you generated for your website.

- A digital signature made by the key-holder of what’s called an intermediate certificate.

- A digital signature made by the key-holder of a root CA certificate trusted by major browsers.

Here’s the verification chain for the website of Digicert, for example, a well-known CA:

DigiCert signing keys have been used at the intermediate and the root level.

In contrast, we’ve shown below how an older browser might decide to trust letsencrypt.com.

In the command below, we’ve use a home-made utility that excludes all of our operating system’s trusted root CAs and relies entirely on a CA from Digital Signature Trust Co., also known as IdenTrust, a company that helped Let’s Encrypt get started by acting as a “CA for the new kid on the block”, starting back in 2015.

(The letters CN=... below are standard nomenclature for Certificate Name is ..., and the IdenTrust root certificate that gave Let’s Encrypt its leg-up is the final one in the verification chain, denoted CN=DST Root CA X3, where the letters DST are short for Digital Signature Trust Co.)

The HTTPS interaction below simulates the situation back when Let’s Encrypt was unknown, and needed the injection of faith from IdenTrust in order for its certificates to be trusted automatically by browsers:

$ manualverify.lua -nobuiltincas -mycas=dst-root-x3.cert letsencrypt.com

+++ Preloaded 0 CA certificates

+++ Added command-line CA from: dst-root-x3.cert

--- Trying: letsencrypt.com:443

--- Chain-of-trust claimed by server

--- 1 /CN=lencr.org

Valid for: lencr.org

letsencrypt.com

letsencrypt.org

www.lencr.org

www.letsencrypt.co

www.letsencrypt.org

--- 2 /C=US/O=Let's Encrypt/CN=R3

--- 3 /C=US/O=Internet Security Research Group/CN=ISRG Root X1

--- Chain-of-trust as resolved in OpenSSL verify()

--- 1 /CN=lencr.org

--- 2 /C=US/O=Let's Encrypt/CN=R3

--- 3 /C=US/O=Internet Security Research Group/CN=ISRG Root X1

--- 4 /O=Digital Signature Trust Co./CN=DST Root CA X3

In this example, similar to what an outdated operating system or browser might experience, the final “your computer found a root CA to vouch for everything below it” step (step 4 above), required the system to refer to Intrust’s DST Root CA X3 to put the stamp of approval on Let’s Encrypt’s certificate chain from that point downwards.

The good news

The good news is that most browsers and operating systems now directly trust the third certificate in the verification chain above.

If we re-run the command, but get it to use our operating system’s built-in CAs automatically (in this case, by omitting the -nobuiltincas option), we get this:

+++ Preloaded 130 CA certificates

--- Trying letsencrypt.org:443

--- Chain-of-trust claimed by server

--- 1 /CN=lencr.org

[. . .]

--- 2 /C=US/O=Let's Encrypt/CN=R3

--- 3 /C=US/O=Internet Security Research Group/CN=ISRG Root X1

--- Chain-of-trust as resolved in OpenSSL verify()

--- 1 /CN=lencr.org

--- 2 /C=US/O=Let's Encrypt/CN=R3

--- 3 /C=US/O=Internet Security Research Group/CN=ISRG Root X1

And that’s just as well, because the DST Root CA X3 certificate that started it all will expire shortly after 3pm UK time on Thursday 30 September 2021 [2021-09-30T14:01:15Z].

The data to look for is labelled Validity Not After:

$ openssl x509 -in dst-root-x3.cert -noout -text

Certificate:

Data:

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number:

44:af:b0:80:d6:a3:27:ba:89:30:39:86:2e:f8:40:6b

Signature Algorithm: sha1WithRSAEncryption

Issuer: O = Digital Signature Trust Co., CN = DST Root CA X3

Validity

Not Before: Sep 30 21:12:19 2000 GMT

Not After : Sep 30 14:01:15 2021 GMT

Subject: O = Digital Signature Trust Co., CN = DST Root CA X3

[. . .]

X509v3 extensions:

X509v3 Basic Constraints: critical

CA:TRUE

X509v3 Key Usage: critical

Certificate Sign, CRL Sign

X509v3 Subject Key Identifier:

C4:A7:B1:A4:7B:2C:71:FA:DB:E1:4B:90:75:FF:C4:15:60:85:89:10

[. . .]

Why does this matter?

Given that Let’s Encrypt’s root CA is just one of more than 140 currently trusted by Firefox, for instance, why focus on this one “magic” expiry date?

We felt this was a timely story because it’s a good reminder of why cryptography and cryptographic progress is often so slow, sometimes taking years to achieve by earned consensus what a dictatorial pronouncement that did nothing to build collective trust could achieve overnight.

Simply put, trust is understandably hard and time-consuming to acquire, but easy to lose.

So, well done to Let’s Encrypt for sticking to its plan of making HTTPS easy and cheap to add even to the tiniest website, and thanks to IdenTrust for vouching for Let’s Encrypt back in the early days.

And thanks to everyone who decided to bite the bullet and adopt HTTPS back when there were still plenty of detractors out there suggesting that HTTPS was just a needless complexity thrust on us by online giants such as Facebook and Google, who clearly had the staff and the budget to do it easily.

Lastly, to those who still claim that HTTPS is an unnecessary evil that plays into the hands of cybercriminals because they, too, can now easily get HTTPS certificates if they want, don’t forget that crooks who wanted to use HTTPS were perfectly able to do so long before Let’s Encrypt came onto the scene.

After all, in the days when cybercriminals still had to stump up credit card details to pay $99 for a TLS certificate to make their sites look “mainstream”…

…do you think for a moment that they were using their own credit cards?

Or do you think they were using card details that they’d slurped up with ease from websites that refused to use HTTPS “because to do so would play into the hands of cybercriminals”?

Josh

Fantastic post, kept me engaged throughout.

Nice work Paul

Paul Ducklin

Thanks for your kind words. Glad you enjoyed it.

James M

Let’s Encrypt is great! Thank you for posting about. Certifying the web is a great goal to have.

However, Sophos UTM trusts Let’s Encrypt CA whilst Sophos XG/XGS does not. Is it possible we can have a commitment for Let’s Encrypt support for SSL/IPSEC VPN and User/Admin Portal?

Paul Ducklin

I can’t answer that, I’m afraid… but if you would like to make your comment directly via your usual support channels, I’m sure someone will be listening :-)

JoseCortes

Nice post. We need made any change in our Sophos XG with the IdentTrust DST Root CA X expiry ?

Thank you.

Paul Ducklin

I have to be honest… I’m not sure, as I don’t have an XGS of my own handy ATM. I guess we’ll find out tomorrow (Thursday 30 September – I mistakenly wrote Wednesday 30 September 2021 in the article, but it’s fixed now), because Naked Security and Sophos News both use Let’s Encrypt certificates.

At worst, I assume you will have to upload the LE Root certificate and “bless” it for your own network, but we can’t answer support-type questions on Naked Security, I’m afraid, so you will have to go through “usual channels” for official advice.

Harpreet

Great post! Keep it coming :)

Paul Ducklin

Thanks… if you keep reading then I’ll keep writing :-)

Ariel Deil

Amazing.

Could this be the reason why I had some Mobile users reporting yesterday night at 23:00 (Israel Time) about getting a err_cert_authority_invalid error page on chrome?

Although the websites certificate validity was until oct 2021.

It was resolved after i forced a renew to the certificate.

Paul Ducklin

Without knowing the details of the certificate chains that were not accepted (or what web filtering smight be in place between the users’ browsers and the sites they were visiting), it’s impossible to say what happened.

If the sites were working before, and stopped working only yesterday, it doesn’t sound as though it could be related to a certificate expiry dated today. (In fact, as I write this, the aboivementioned IdenTrust root cert still has 90 minutes to go :-)

FWIW – and I hope this did not cause confusion – the very first version of this article listed the date as “Wednesday 30 September 2021”, which doesn’t exist… we quickly corrected that, but apologies to people who saw “Wednesday” and assumed that the *day* was correct, rather than the *date*.

Sergei

We have also seen some issues in WAF starting today, all seem letsencrypt issues. Should be fun tomorrow if you are an UTM WAF client ….

Paul Ducklin

Aha, please see comment chain below starting with @Ivan, and please take a look here for further info/updates:

https://support.sophos.com/support/s/article/KB-000042993

HtH.

Sammeer

Awesome (both content and style) post. Amazingly readable with depth of content seamlessly abridged in code!! The code.. u just couldn’t resist. Could you?

Paul Ducklin

Thanks for your kind words…

…but the “code” that I showed comes down to three invocations of the “openssl” command, so I wouldn’t really call it code :-) Just a small, illustrative example.

Ivan

Hi Paul,

Hmm too bad the Sophos UTM developers did not get this memo, The Sophos UTM WAF is currently supplying users with the the old R3 chain thus causing cert errors for quite some users.

Paul Ducklin

Have you let them know? Please do…

…I will too, thanks.

(Although the certificate hasn’t quite expired yet, has it? It’s currently 2021-09-30T13:03:00Z, but the R3 cert expires on 2021-09-30T14:01:15Z, doesn’t it? Hmmmmmm. But I’m reporting this anyway :-)

Ivan

Yep i just did, Thanks!

/Ivan

Paul Ducklin

I did too, I think they’re on it now :-)

Paul Ducklin

We’ll soon be publishing updated certs to sort this out. In the meantime, if you simply delete the expired certs from your UTM by hand then the problem should solve itself…

…instead of trying to construct a certificate chain in the UTM and supply it during the TLS setup, the client will build the chain for itself, starting with your own website’s certificate, and validate it. So, assuming the client itself trusts the new Let’s Encrypt root cert, that will verify your website’s Let’s Encrypt certificate as far as the new root CA and all will be good.

When the UTM gets the new root cert (next few hours?), it will go back to pre-building a chain to send to the client, and the clients will he happy with that pre-built chain, too.

For more info, please see:

https://support.sophos.com/support/s/article/KB-000042993

The KB article above includes a handy screenshot showing how to locate the expired certificate if you want to delete it by hand. Look for the certificate name “Digital Signature Trust Co. DST Root CA X3”. After deselecting it, turn Web Protection off and immediately back on again to force the configuration change.

HtH.

OneOfTheDamons

Looks like this is affecting other vendors too. See [REDACTED] for example

Laurence Marks

Firesheep was one of the stimuli to get websites moving to full-time HTTPS. I would argue that a greater one was Google’s announcement that every HTTP page that Chrome rendered would have a red warning banner.

Back in that pre-Let’s Encrypt era one of the websites I was managing was a content-management system tuned for high-school graduating classes–1963 for me. I had acquired our own domain and brought that to the hosting company. A few months later one of my over-vigilant classmates asserted that he would not visit the website because he was certain that he would immediately be hacked. I asked the hosting company to implement HTTPS. They responded that paying $200 for a two-year certificate would eat almost all of our $220 two-year subscription fee and wouldn’t be feasible. Let’s Encrypt had been operational for about two months at that time. I directed them to it, and 30 days later they emailed me and ask me to test their implementation (which worked fine).

Paul Ducklin

I’d suggest that Facebook (see our “open letter” from a decade ago in the article above), love it or hate it, deserves a lot of credit for being one of the first really big networks to adopt HTTPS for everything. Ironically, Google’s push to “name and shame” non-HTTPS website was a bit of a double-edged sword, because it did provoke a visible backlash from a vocal minority. (It’s one thing for a super-rich megacorp to switch its own network over to HTTPS only, but quite another to publicly rebuke everyone else for not following suit.) I suspect, however, that a more urgent reason for many websites to switch to HTTPS was not so much Google’s public red flag in the browser programme, but the ad behemoth’s decision to start giving HTTP-only pages a lower page rank that an equivalent HTTPS site… the former might make you look a bit less attractive while the latter actually makes you less attractive, or at least less visible :-)

Jacob Højmark Nielsen

Thanks for an interesting article. However, there seems to be a misunderstanding that encryption – in this case from Let’s Encrypt – is the same as trust, but I believe that trust should be attached to online identities which Let’s Encrypt or any other Domain Validated certificate only provides to a very limited – some will argue no – extent.

This again opens up for a false impression of trust, which you’ve addressed yourself a little more than 4 years ago (see below link).

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2017/03/30/lets-encrypt-issues-certs-to-paypal-phishing-sites-how-to-protect-yourself/

Quote from APWG report from November 2020:

“Now, 80 percent of phishing sites have SSL encryption enabled – which surprisingly is even higher than

web sites in general,” said John LaCour, CTO of PhishLabs. (According to a Q-Source survey, as of

October 2020, only 66.8 percent of web sites used SSL by default.)

“Not surprisingly, most SSL certificates used by phishers were Domain-Validated (“DV”), which is the

weakest form of certificate validation,” said LaCour. PhishLabs looked at 53,189 certificates used on

phishing sites, and found that 91.3 percent were DV), while 8.6 percent were OV (organization

Validation) certs, and just 0.1% were Extended Validation (EV).

Another key finding is that in Q3, 40 percent of all SSL certificates used by phishers were issued by a

certificate authority that offers free certificates: Let’s Encrypt.

Paul Ducklin

I don’t think that this article suggests that HTTPS in any way validates or speaks to the validity of the content a website. We do clearly explain that HTTPS helps to ensure confidentiality and integrity of what you download. But indeed, as you say, crooks can use HTTPS just as easily as legitimate operators.

As for the added value of (and even the use of) EV certificates, that boat sailed some years ago when major brands, notably Google, asserted that they added little or no value and stopped using them.

Anonymous

Ok, thank you for clarifying – and yes, as the statistics say: crooks can now easily use HTTPS due to the poor validation in most of the free DV certs. To me this is the biggest problem and I think this should be addressed as a very big problem for all of us. The backbone of certificates must be the identity, it is trivial to keep promoting encryption.

The funny thing is that EV certificates was a great initiative in terms of identity – a lot of other things were certainly not great – but as you’re saying the browsers chose to make the EV certificates invisible again. Ever never been able to find an explanation why, but as you may now the European eIDAS is now promoting QWAC certificates which is more or less the same as an EV certificate. More info here: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12528-EU-digital-ID-scheme-for-online-transactions-across-Europe_en

Paul Ducklin

How does the “identity” of a certificate prove the validity or the accuracy or the quality of the site behind the encryption? Part of the pushback against EV certificates and the “green glow of excellence” that some browsers painted them with, is that those “green” certificates did give the impression that someone had verified the editorial process or the truthfulness of everyone publishing content on the site, not merely that the person presenting the certificate demonstrated that they had control over the server, and some apparent right on paper to do so, at the time the certificate was issued.

So the two-fold problem with EV certs was, and is:

* Not much of a barrier to crooks who are spending someone else’s money. Heck, if the crooks can set up a fake landline in your town for realistic phone calls, and register a happy-sounding domain under a front company registered inexpensively for the purpose of running their scam (there are plenty of on-line services that offer UK companies for £12, for example), the additional hassle of getting an EV certificate seems pretty minor, all for a “green glow” that is either ignored or misinterpreted anyway.

* Much of a barrier to small businesses, charities and so on who are trying to do it by the book. So the people you’d really like to come to the “encrypt and shield genuione traffic from tampering” party are unlikely to be convinced to spend even *more* time and money on certificates than they weren’t spending anyway.

A certificate issuer isn’t there to make value judgments about the content of the site it’s verifying, just checking some boxes to say that the organisation that says it runs the site seems to exist in some basic, testable fashion. So even EV certificates don’t tell you much, or even anything, about the reliability, ethics or even the genuineness of the org. applying for the certificate, although they *seem* to do so, or can easily be misrepresented by the owner of the certificate as imlying that the company has been vetted for the integrity and quality of its wen content, rather than merely checked out for its existence.

Jacob Hojmark Nielsen

The entire backbone of DV, OV and EV certificates are build on the level of trust and thus identity. This applies to all certificate types all though some certificates do not offer the DV option i.e. document signing certificates. Why? Because DV certificates do not prove who you are, DV certifcates prove that you have control over a domain hence the name Domain Validated. OV and EV certifcates are attached and issued to a company – in all cases you’ll see an OV or EV certificate, a human being has vetted and actually looked at the application in order to verify if is ok to issue a certificate according to the info from the application. This is not a 100% bulletproof system – but it is significantly better and more secure in order to identifying the company behind the website. No certificate can tell you anything about the quality nor the accuracy (I’m not even sure what you refer to here) of the website. From the statements in your latest post I assume that you do not know in details what it takes to get an EV SSL certificate, correct? My theory would be, that if it was really that easy to get an EV SSL certificate, I believe many more of the crooks would do so…

Paul Ducklin

I’ve read of researchers who were able to acquire EV certs for well-known company names simply by (lawfully) registering a company with the name they wanted to impersonate in a different jurisdiction, putting in themlseves as the contact, and paying the EV certificate verification fee. That’s to get an EV certificate with a *misleading* vcompany name on it, let alone an EV certificate in a name that no-one else is using elseqhere. There are online services in the UK right now offering registrations with Companies House for just £13 (£12.99, actually, you get a penny back).

I think the bottom line here is simple: if there were no Let’s Encrypt, then we’d still have loads of genuine sites that were HTTP only, and *all* the users of *all* those sites would be at risk *all* the time of having malicious content inserted into their content in transit by *all* crook with access to an interception point (e.g. a router at coffee shop). At the same time, we’d still be accustomed to HTTP-only sites, so the crooks still wouldn’t bother with certificates at all, whether of a DV, EV or home-made sort.

Now, we have very widespread adoption of HTTPS, including by the crooks, and although that makes some types of web filtering harder, *it only makes it harder for products or users that still rely on using the loophole of having most content unencrypted in transit and therefore snoopable/filterable without forethought or consent*.

And you can still buy EV certifictes if you want, so if you think they are a differentiator for your company, then the choice is yours. If you think an EV certificate will boost your company’s credibility it’s not a huge price to pay. But for people who wouldn’t otherwise spend $100, and would go unencrypted if there were no free certs, it’s hard to see how something like Let’s Encrypt has made the world *less* secure.

Jacob Højmark Nielsen

Now this I can agree to, Paul.

To me it’s extremely important to differientate between encryption and identity; it is without a doubt very good that Let’s Encrypt has managed to solve the task of encryption for the world – what is not so good, is that the public doesn’t know the difference between encryption and identity and that the industy has chosen to not make this difference visible. We in the industry must take the full responsibility for this misunderstanding and strive to inform the public about it in the best and most easy to understand way.

If you happen to have examples or additional info, you can share with regards to the researchers who’ve managed to obtain rogue EV certs, I’ll appreciate this very much…