An opportunistic botnet that tries (not always successfully) to fly under the radar, Kingminer is nevertheless a persistent nuisance that delivers cryptocurrency miners as a payload. The botnet’s operators may be ambitious and capable, but they don’t appear to have endless resources, so they take advantage of any freely available solution to the problem of infecting machines and spreading, getting inspiration from public domain tools as well as techniques used by APT groups.

This morning, SophosLabs is releasing our report, An insider view into the increasingly complex Kingminer botnet. In this report, we perform an in-depth teardown of the botnet’s tactics, techniques, and procedures, with an eye to giving analysts and incident responders a roadmap for closing off the loopholes this threat uses to its advantage.

The main findings of our research are:

- Kingminer spreads by brute-forcing username/password combinations of SQL servers, and has recently started to experiment with the EternalBlue exploit.

- The infection process may use a privilege elevation exploit (CVE-2017-0213 or CVE-2019-0803) in an attempt to prevent software (or admins) from blocking the attackers’ activity.

- The botnet’s operators prefer to use open source or public domain software (like PowerSploit or Mimikatz ) and exhibit evidence they’re skilled enough to customize their own enhancements.

- They employ tricks like DLL side-loading, a method traditionally used by Chinese APT groups that’s gaining momentum broadly in cybercriminal activity

- The botnet uses a domain generator algorithm (DGA) to potentially change the domains it uses for command and control or payload delivery automatically every week

- If the infected computer is not patched against the Bluekeep vulnerability, Kingminer disables the vulnerable RDP service in order to lock out competing botnets

Download servers

The Kingminer botnet uses two main approaches in hosting the delivered content. The first one relies on servers that the criminals registered and manage themselves, usually using a simple time-coded domain name generation algorithm (DGA). These servers deliver the components with clearly malicious content.

For the not-so-obviously malicious things, the operators use public repositories provided by Github. This is where they store files like the xmrig miner payloads, reflective loader scripts, or the Mimikatz password stealer. These components are not necessarily malicious by themselves, but the context in which they are used (installed without user consent, by infecting the target computers) was clearly malicious.

Time coded DGA

The attackers have embedded an algorithm into the bots that generates domain names using the value of the current date and time. This method has the advantage that the malware doesn’t have to store hardcoded addresses for command and control. Instead, the bots dynamically generated and keep changing with time. This way, if one of the download servers is shut down, the operators don’t have to release new versions of the downloader with the updated download location. Instead, they just register the next domain name, and when the time comes, the botnet will automatically switch over to the new download servers.

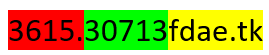

The generated domain names have the following structure:

The yellow part is the core of the domain name. In the observed cases it was either fdae.tk, fdae.com or fghh.com, but strings found in the side-loading DLLs suggest that additionally the attackers could potentially use fdae.ga or fdae.cf in the domain cores.

The domain core is completed with the green prefix, combined from the current year/month/week value (week=day/7 in this case, rounded down), using only the last two digits of the year in the form: yymmwwyy. The resulting number is converted to a hexadecimal number.

In the example shown above, the date part of the domain is 0x30713, which when converted to decimal form gives 198419, making the date values to be yy=19, m=8, w=4. This domain name would have been used during the 5th week in August, 2019.

The red subdomain part is created from the minutes and seconds value of the current time.

Even though this mechanism makes it possible to use a different server very week, the botnet operators never use this opportunity to its full potential – the vast majority of the potential server names are never used and never registered and many components use hardcoded locations.

Github repositories

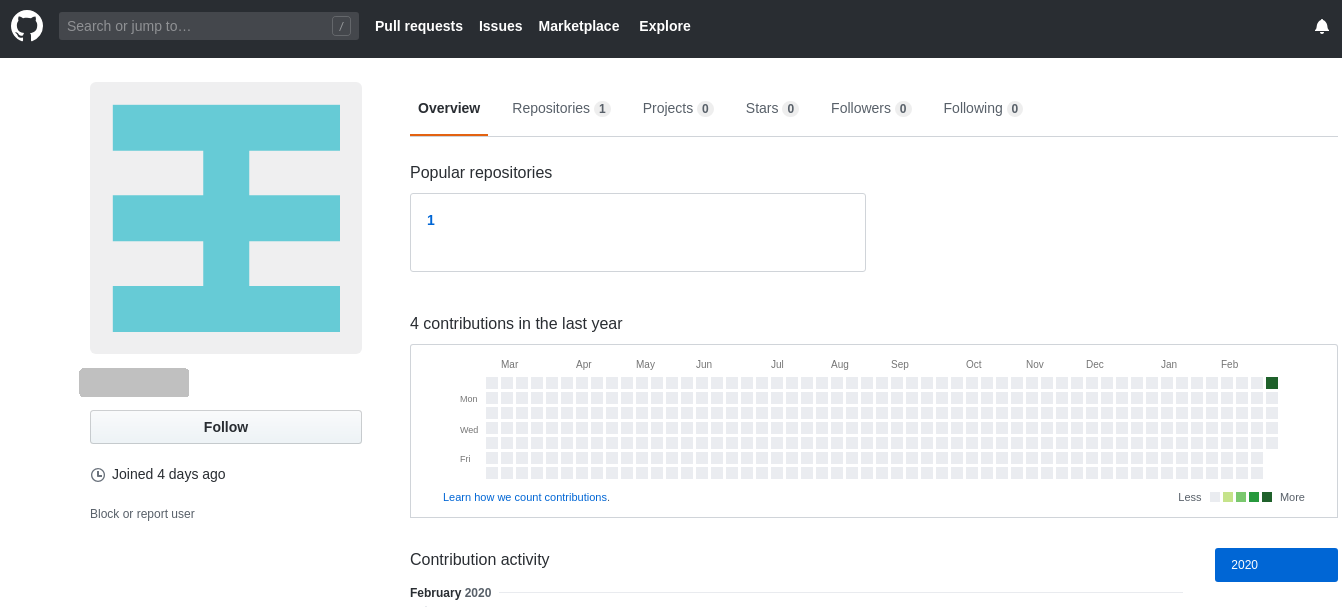

We have found over 20 Github user accounts that were used to deliver the contents of the Kingminer botnet.

These repositories are not very active, in the sense that only one or two commits are ever made to them. The first commit usually is an upload of the actual malicious components, then optionally an update was made, likely to avoid detections that were added in the meantime by security products.

The typical content of a repository consists of the following files:

- txt: 32-bit miner, XOR encrypted

- cab: 32-bit miner side-loader CAB package stored in XML

- txt: 32-bit miner, XOR encrypted

- cab: 32-bit miner side-loader CAB package stored in XML

- txt: 32-bit control panel applet, BASE64 encoded

- txt: 64-bit control panel applet, BASE64 encoded

- txt: 32-bit Mimikatz, XOR encrypted

- txt: 64-bit Mimikatz, XOR encrypted

- txt: reflective loader, BASE64 encoded

Infection process

So far, the only confirmed infection method that we could identify was the attack in which SQL servers experience brute-force probing with username/password combinations; When successful, the attackers insert SQL command scripts that load the rest of the components.

Recently we have seen signs that the operators of the Kingminer botnet started experimenting with an EternalBlue spreader. We have witnessed this script being delivered to the infected systems but have not observed a successful infection as a result of the exploitation.

The EternalBlue script is very much the same as the implementation found in another miner botnet, Powerghost/Wannaminer (which, itself, is based more or less on PowerShell Empire).

Downloader script

Whichever infection method is used, the first step is the execution of the downloader script, responsible for fetching and installing the rest of the botnet components.

The attackers have crafted custom payloads to the target operating system, deploying different version for 32-bit and 64-bit Windows systems.

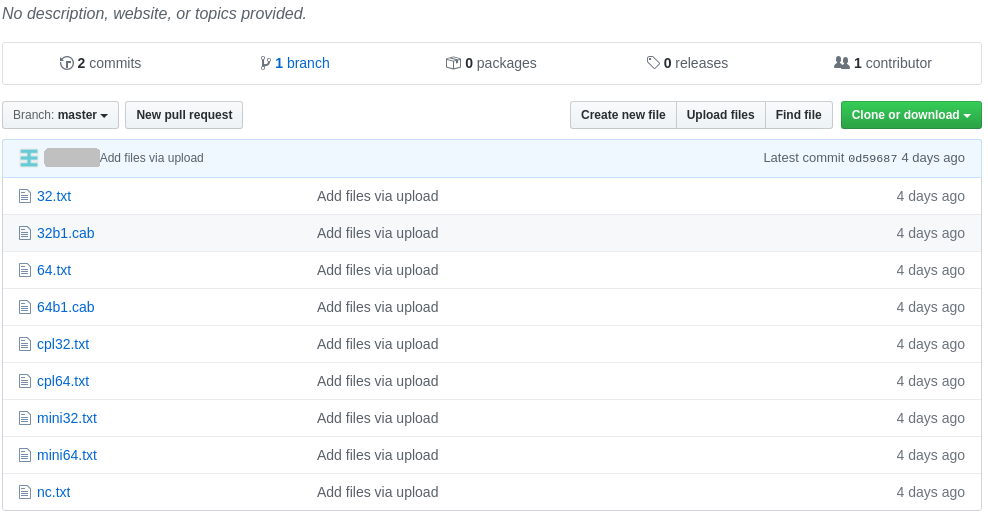

The downloaded payload is not a plain executable file. Rather, it is packaged into an XML file. The XML file contains either a ZIP or a CAB archive, that, in turn, contains the necessary components.

Payload loading

Once the downloader script fetches the payload from the attacker’s server, it executes the payload, usually by utilizing the DLL side-loading technique, which has been popular with Chinese APT groups [1] for a long time. This method makes use of the peculiarities of the Windows operating system related to directory search order.

The payload that is downloaded from the remote server is originally packaged in an XML envelope:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <root xmlns:dt="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:datatypes" dt:dt="bin.base64"> TVNDRgAAAABsiQwAAAAAACwAAAAAAAAAAwEBAAMAAAAiCQAAdgAAAE4AAxUAhgAAAAAAAAAA 7jriTCAAZHdtZXIuZXhlAAAkAgAAhgAAAABLUJKSIABkdXNlci5kbGwAABwkAACqAgAAAEtQ 5IggAHgudHh0AG/LdHIEOwCAW4CAjQUgt8VxEwCwUwAkIgAAAADvXqnrvqa+UOVR0mSSIhLQ

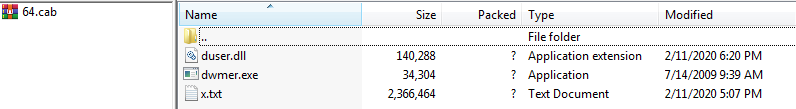

When unpacked, the content of a typical 64-bit package looks like this:

The main components in the packages are:

- A clean, and digitally signed, trusted executable (exe in the example above)

- A malicious loader DLL

- The encrypted payload (txt)

The purpose of the clean executable is to have an external dependency on a Windows DLL library, which is a roundabout way to trigger the operating system to execute the malware, without directly calling the malware DLL.

When the downloader script executes the (benign) .exe, the operating system tries to resolve the DLL dependency, which it does by trying to find the DLL.

The first location it searches is the directory that contains the executable – ironically not the system32 directory, where Windows houses (and protects) all its legitimate DLL files. So, it automatically loads the malicious DLL, and executes the entrypoint function, which in turn loads the encrypted payload into memory, then decrypts it.

Then the malicious loader DLL uses an in-memory PE loader to convert the decrypted block of memory into a proper executable image, similar to how the operating system would do it (i.e. allocate the memory for the sections, set the section attributes, resolve the imports, locate the entry point). Finally, it loads the payload at the entry point of the executable.

If the loading is successful, the loader will enter an infinite waiting loop. This is done because the payload started in a separate thread, the main thread can never stop, and the miner can run indefinitely—an important consideration, because the DLL itself doesn’t create any methods to ensure its own persistence.

Malware fixes BlueKeep to block other infections

One of the more interesting components is a simple VBScript code that checks the Windows internal version number, searching for versions 5.0 (Windows 2000), 5.1 (Windows XP), 5.2 (Windows XP 64 or Windows Server 2003), 6.0 (Windows Vista or Windows Server 2008), or 6.1 (Windows 7 or Windows Server 2008 R2) – all of which are no longer supported by Microsoft, and potentially vulnerable to the BlueKeep exploit.

If the malware identifies that it is running on any of the vulnerable systems, the code goes on to list the installed hotfixes with the command and searches for the ones related to Bluekeep:

kb4499175: Windows 7 SP1 kb4500331: Windows XP, Windows Server 2003 SP2 KB4499149: Windows Server 2008 SP1 KB4499180: Windows Server 2008 SP1 KB4499164: Windows 7 SP1

If it finds none of the hotfixes (and thus the system is vulnerable to a Bluekeep attack), the script disables further Remote Desktop (RDP) .

The intent is likely to disable a possible infection vector that other cryptomining botnets could use to infect the computer. Although this exploit is not widely used, a couple of botnets were reported to have used it.

Xmrig miners

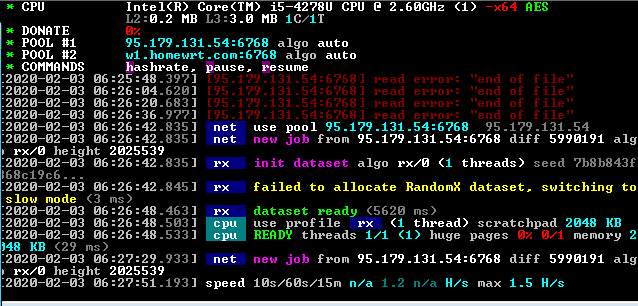

The primary payload and the most important component of the botnet is obviously the cryptominer program. In all of the identified cases, this was a variant of the public domain xmrig miner.

The miners are compiled into DLLs, the loader code locates the export named a and executes it. This is an unusual design; In other attacks of this type, the miners are compiled into standalone executables.

Interestingly, in addition to this main export, the miners also have the same SetDesktopMonitorHook and ClearDesktopMonitorHook as the side-loader DLLs, and both functions call the main exported function a.

This means, that in theory, the miner itself can serve as a side-loaded DLL, loaded by the clean application. So far, we have not seen scenarios that make use of this design.

The miners have two pool addresses configured (95.179.131.54 and w1.homewrt.com in the example above) to which they connect and upload the results of mining Monero.

Conclusion

Kingminer is one of the many medium-sized criminal enterprises who are more creative than the groups who simply use builders purchased from underground marketplaces. The threat actors behind Kingminer build their own solutions. In that, they are cost-effective, adopting open source solutions available in public code repositories.

As long as the sources of new tools and exploits are published, groups like Kingminer can and will continue to implement them into their arsenal, accelerating the adoption of the exploits and exploit techniques in the lower level tiers of criminality.

IoCs

Indicators of compromise for this article have been posted to the SophosLabs Github. Malware related to this threat will be detected as Troj/Kingmine-B.

Users of Sophos endpoint products with EDR can perform proactive threat hunts for Kingminer on their own network using the Kingminer non-deterministic queries posted to the Early Access Program’s community forum.

Fırat Meray

Really good article. Thanks