Remember WannaCry?

That’s the infamous self-spreading ransomware attack that stormed the world in May 2017.

WannaCry was an unusual strain of ransomware for two main reasons.

Unlike most ransomware we’ve seen in the past 30 years (yes, it really is that long!) WannaCry was a computer virus, or more precisely a self-spreading worm, meaning that it replicated all by itself, finding new victims, breaking in and launching on the next computer automatically.

WannaCry broke in across the internet, jumping from network to network and company to company using an exploit – a security bug in Windows that allowed the virus to poke its way in without needing a username or a password.

And not just any exploit – WannaCry used an attack called ETERNALBLUE that was allegedly stolen from the US National Security Agency by a hacking crew known as Shadow Brokers .

The good news is that, even back at the time that WannaCry burst onto the internet, a patch to fix the ETERNALBLUE security hole was available, issued two months previously by Microsoft as part of the March 2017 Patch Tuesday update.

If you’d patched within the past two months, you were largely immune to WannaCry, and could therefore stand down from red alert.

Even if you detected network attacks coming from existing, unpatched, infected victims, those ETERNALBLUE probes would have bounced harmlessly off your up-to-date devices.

Of course, not everyone had patched within that two month window, and so the malware spread far and fast, demanding $300 per infected computer from something like 200,000 victims in short order.

WannaCry won’t die

Well, guess what?

Not everyone has patched even now, more than two years later, and WannaCry is not only still alive (and ignoring the kill switch that was designed to stop it), but possibly more alive than ever.

Sophos experts Peter Mackenzie, Fraser Howard and Anton Kalinin have just published a must-read paper that will tell you why, and how.

Fortunately, although we’re still seeing huge amounts of WannaCry activity, we aren’t seeing many people actually getting their data scrambled by it.

And because people who are infected aren’t themselves visibly being affected by unwanted encryption and ransom demands, they don’t realise they’re spreading copies of it.

But how on earth can a destructive virus more than two years old, one that was patched against even before it first appeared, continue to spread like crazy?

And how come it’s still alive but no longer drawing attention to itself by leaving a sea of scrambled files and ransom demands in its wake?

More importantly, what can we do to stop it now?

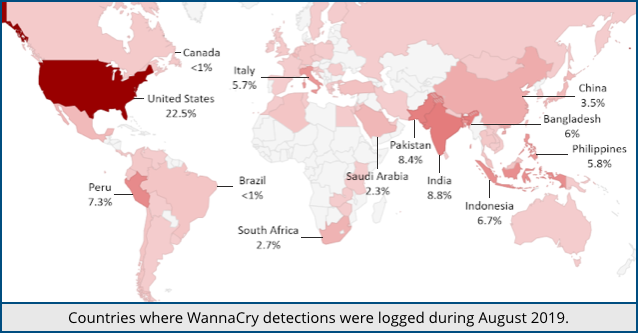

The data that our experts analyse in their report is fascinating:

- More than 12,000 WannaCry variants were found in the wild, two years after the malware was supposedly conquered for good.

- More than 5,000,000 attempted attacks against unpatched computers were blocked in the last three months of 2018 – and that’s just the ones where Sophos Endpoint Security was installed and reported back to us.

- More than 97% of unpatched computers under attack were runnning Windows 7, so this is not just a story about forgotten Windows XP devices.

- A few people actually paid the ransom even though there’s no point in doing so. The crooks behind the relevant Bitcoin addresses aren’t monitoring payments or providing decryption tools.

What to do?

We don’t want to spoil the paper but we will say that the only reason most of the contemporary WannaCry variants don’t scramble the computers they infect…

…is because the file-scrambling part of the malware is corrupted.

In other words, if you haven’t patched, and you do get infected, but you don’t get your files ruined, you got lucky.

You were saved by accident rather than by design – from WannaCry, that is, but who knows who or what else has been wandering round your network in the more than two years since you last patched?

Read the paper and learn what what to do – there are apparently millions of people in our midst who desperately need our help and advice, for the greater good of all.

rrogers31

Anybody here remember natural evolution? Most successful parasites don’t kill the host; just propagate.

Barbara Laumann

I am a non-tech 76-year-old & am so grateful to SOPHOS. My grandchildren know more than I do about computers & I phones. You have made my life so much better with the easy to use protection.

Thank you, Thank you Thank you,

Barbara

Rainbow_Unicorn

you can blog about it but do not take any action to fix it .. you are like a police officer sitting in

black & white 5 feet from a drug dealer and seeing on going crime go by.. why you do not take any action?

because theres within 10mins yet other dealer at same spot.. you see and know what pc is sick with wanncry

its ip and mac address what network it is and so on .. but you can not or do not take any “cleaning” action ..

cos its illegal to do so.. there should be taken “cleaning action” to do this kinds stuff .. but no ..

it would be easy to code simple wannacry sniffer and with a cleaner but thats illegal to do so ..

hmm.. so let the world burn .. burn baby burn.. :| why you dont take any action?..

Mark Stockley

WannaCry relies on machines that are unpatched and unprotected by anti-malware software in order to spread. Those unprotected machines then attempt to infect protected machines around them, continuously.

The protected machines detect and stop the attempted infections, which triggers a huge number of logged events. Those events are often what alert companies to the presence of unprotected machines on their network.

The paper was written by Peter Mackenzie, Fraser Howard and Anton Kalinin based on their experience of taking action against WannaCry and what they discovered in so doing. None of them writes papers for a living.

If your company is unlucky enough to be in the grip of a virus outbreak, Peter digs you out and figures out what happened. Fraser and Anton spend their days disassembling malware and working out how it works and how to improve detection of it.

Paul Ducklin

You answered your own question when you noted that hacking back to kill off WannaCry on the attacking computer is “illegal to do”.

It would also IMO be unsafe, unreliable and unfair, and here is why.

When an attempted infection hits a protected computer and gets blocked, all we know about the attacker is the IP number given as the source address from which the ETERNALBLUE exploit came.

In theory, we could hack back to see if the attacking computer was itself vulnerable, and if so we could ‘infect’ it with a program to remove the malware. But in most cases where the attack came from outside your own network, the attacking IP number would probably be a firewall or a router – in which case our hack-back would hit the wrong device. At best, our counter-attack would do nothing. At worst it might trigger an alarm or crash the computer. Most countries would consider this to be an attempt at unauthorised access – purposely poking an exploit at someone without permission – and treat it as a ‘computer misuse’ crime.

Hacking back wouldn’t patch the infected computer anyway, even if the unauthorised access attempt were to succeed, so this would be a short-lived victory. When the computer got attacked again, it would get reinfected and start trying to spread again; we would detect when it tried to hit a protected computer; then we’d hack back again; and so things would continue.