Thanks to Peter Mackenzie of Sophos Support for his behind-the-scenes work on this article.

In the year since the “shock and awe” of WannaCry and NotPetya – outbreaks that spread globally in a matter of hours – ransomware has been making a lot less noise.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that it’s had its day, but reports of the demise of ransomware have been greatly exaggerated, as they say.

While cryptomining and cryptojacking have been sucking all the air out of the press room, a snowball that started rolling well before anyone had ever heard of WannaCry has been gathering pace and size.

The snowball is a trend for stealthier and more sophisticated ransomware attacks – attacks that are individually more lucrative, harder to stop and more devastating for their victims than attacks that rely on email or exploits to spread.

And they do it in a way that’s hard to stop and easy to reproduce.

WannaCry’s reliance on an exploit stolen from the NSA (the USA’s National Security Agency) made its success hard to replicate, and its promiscuous spread attracted the attention of law enforcement everywhere while leaving countless copies of the malware to be analysed by researchers and security companies.

The criminals behind targeted ransomware attacks have no such limits. They rely on tactics that can be repeated successfully, commodity tools that are easily replaced, and ransomware that makes itself hard to analyse by staying in its lane and cleaning up after itself.

And while the footprint of a targeted attack is tiny in comparison to an outbreak or spam campaign, it can extract more money from one victim than all of the WannaCry ransoms put together.

Targeted attacks can lock small businesses out of critical systems or bring entire organisations to a grinding halt, just as a recent SamSam attack against the city of Atlanta showed.

For every Atlanta-style attack that hits the headlines though, many more go unreported. Attackers don’t care if the victims are big organisations or small ones, all that matters is how vulnerable they are.

In fact, the three examples of ransomware we’ve chosen for this article, Dharma, SamSam and BitPaymer can be thought of (allowing for considerable overlap) as ransomware aimed at small, medium and large businesses respectively.

All businesses are targets, not just ones that hit the headlines.

For example, a recent investigation by Sophos revealed that SamSam’s apparent preference for the healthcare and government sectors was an illusion. The majority of the SamSam victims uncovered in the investigation were actually in the private sector but none of them had gone public, whereas some government and healthcare victims had.

The anatomy of a targeted attack

The specifics of targeted attacks evolve over time, vary from hacking group to hacking group, and can be adapted to each individual target. Despite that, they show remarkable similarity in their overall structure.

In a typical targeted attack, a criminal hacker:

- Gains entry via a weak RDP (Remote Desktop Protocol) password.

- Escalates their privileges until they’re an administrator.

- Uses their powerful access rights to overcome security software.

- Spreads and runs ransomware that encrypts a victim’s files.

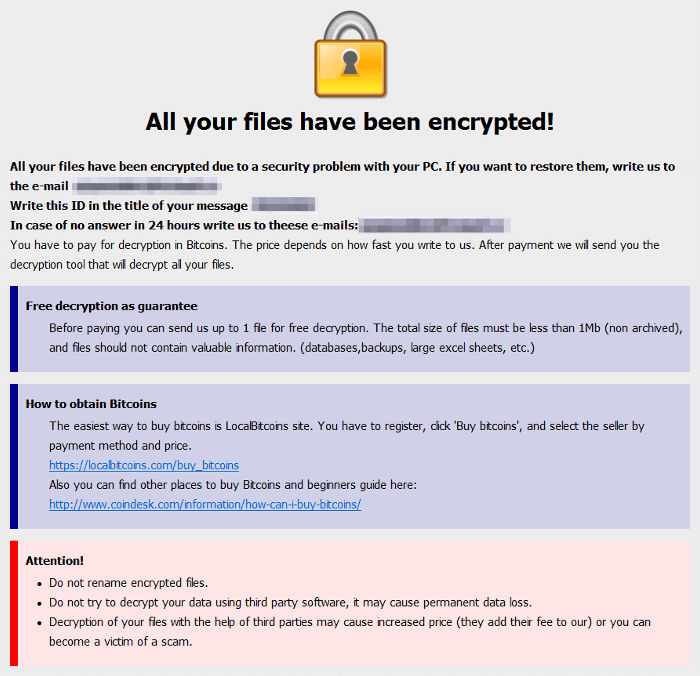

- Leaves a note demanding payment in return for decrypting the files.

- Waits for the victim to contact them via email or a dark web website.

The similarity between attacks and attackers isn’t the result of coordination, but a convergence around a method that works reliably, netting the criminals using it huge payoffs.

That convergence goes as far as including details like special offers: while the ransoms they demand vary significantly, Dharma, SamSam and BitPaymer attacks all offer their victims the opportunity to decrypt one or two files for free to prove that they can do it – ransomware’s equivalent of a kidnapper’s “proof of life”.

Although the outline of each attack is very similar, scripted even, what makes targeted attacks so fearsome is that the attackers are on hand to adapt and improvise.

In a targeted attack the assailant’s job is to break into the victim’s network and maximise the chances of the ransomware succeeding in its malevolent task, and the adversary most likely to ruin the attacker’s day is security software operating as one of several layers of overlapping protection.

Writing ransomware that isn’t detected by security software is no easy task, so attackers will often look for a way to outflank it by exploiting operating system vulnerabilities that let them elevate their privileges.

If they can make themselves an administrator, an attacker will be permitted to run powerful administration tools, like third party kernel drivers, that can disable processes and force delete files, bypassing the protections put in place to stop the attackers uninstalling security software directly.

Security software still isn’t helpless though. Set up correctly, it can defend itself by blocking the legitimate third party utilities that might be used to undermine it.

Variations on a theme

The coup de grâce in a targeted attack comes when the attacker has manoeuvred themselves into a strong enough position to run their ransomware unencumbered.

Now lets look at some of the ransomware itself.

Dharma

Dharma (also known as Crysis) attacks seem to run to a simple, cookie cutter script with attackers breaking in and then downloading the things they need to execute an attack from the internet as if reading from a todo list: exploits to escalate their privileges, admin or troubleshooting tools to tackle security software, and finally the ransomware itself.

Although simple, the attacks show more variability, and occur at a much greater frequency, than either SamSam or BitPaymer attacks, which may indicate that Dharma is used by multiple groups.

Once the attacker is inside the victim’s network they place the ransomware on one or more of a victim’s servers manually. Consequently, attacks are often limited in scope, affecting just a few servers.

Most Dharma attacks seem to have affected small businesses of up to 150 users, although it’s not known if this is down to deliberate targeting or simply a side-effect of something else.

Ransom demands are made over email, using an address specified in the ransom note, away from prying eyes.

SamSam

SamSam malware first appeared in December 2015 and since then more than $6 million has been deposited into SamSam Bitcoin wallets.

The pattern of attacks and the evolution of the SamSam malware suggests that it’s the work of one person or a small group. Attacks are infrequent (around one a day) compared to other kinds of ransomware, but are devastating.

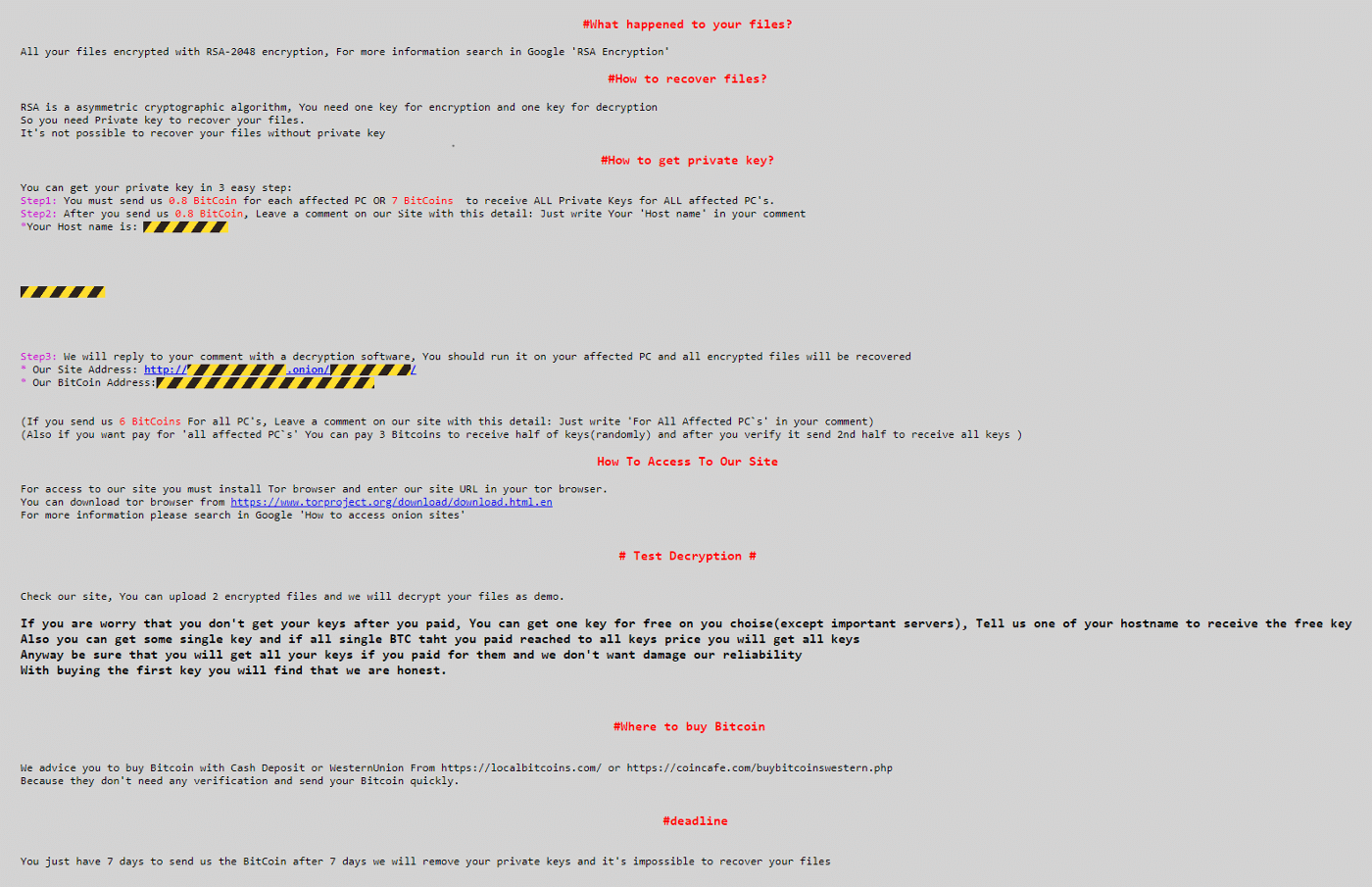

After breaking in via RDP, the attacker attempts to escalate their privileges to the level of Domain Admin so that they can deploy SamSam malware across an entire network, just like a sysadmin deploying regular software.

The attacker seems to wait until victims are likely to be asleep before unleashing the malware on every infected machine simultaneously, giving the victim little time to react or to prioritise, and potentially crippling their network.

A ransom note demands payment of about $50,000 in bitcoins and directs the victims to a dark web site (a Tor hidden service).

Each victim has their own page on the site where they can ask the attacker questions and receive instructions on how to decrypt their files.

To find out more about SamSam, read Sophos’s extensive new research, SamSam: The (almost) six million dollar ransomware.

BitPaymer

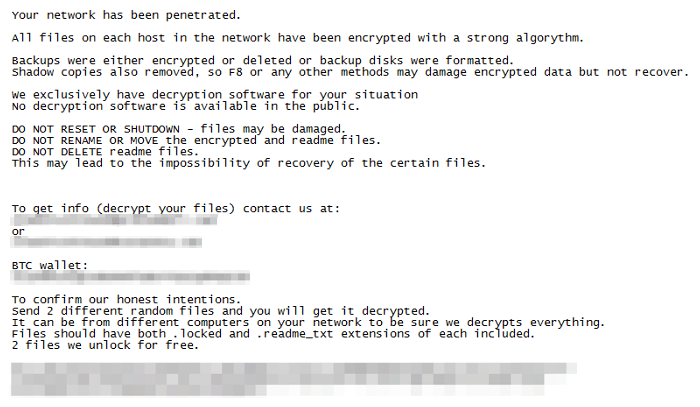

The most mysterious and sophisticated malware on our list is BitPaymer. Little is known about this elusive malware, or how it’s deployed (you can read about one of the tricks it uses to hide itself in our article, How BitPaymer ransomware covers its tracks).

What seems certain is that this ‘high end’ ransomware has raised a lot of money for its creators. Six-figure ransom demands as high as $500,000 have been reported and analysis of known BitPaymer Bitcoin addresses shows that it’s raised at least $1 million in the last month alone.

Ransom notes contain email addresses at secure email providers but the method for agreeing payment varies: some simply include a Bitcoin address while others list a dark web URL instead, like SamSam. In some attacks the victims have also been threatened with doxing.

What to do?

Targeted attacks may be relatively sophisticated but the criminals behind them aren’t looking for a challenge, they’re looking for vulnerable organisations. The best way to get yourself off an attacker’s hit list is by getting the basics right: lock down RDP and follow a strict patching protocol for your operating systems and the applications that run on them.

If an attacker does get on your network then make sure they’re met with layers of overlapping defences, a well segmented network, user rights assigned according to need rather than convenience, and be sure that your backups are offline and out of their reach.

We recently published a detailed guide on how to defend yourself against SamSam ransomware, that includes specifics on how to lock down RDP, suggestions on how to organise your user accounts and more. The advice and approach in it are applicable to all the targeted ransomware mentioned in this article.

Roland Schmid (@r_u_schmid)

many users do not really close their rpd session (just close the remote window). Am I at risk when using rpd sessions within a local network?

Paul Ducklin

Internal RDP (where you administer the server from your desk at work rather than all the way from home) still needs to be done securely. Crooks who have got into one part of your network, perhaps with little or no privilege, will inevitably look around for ways to “improve” their position by moving across and up, so to speak…