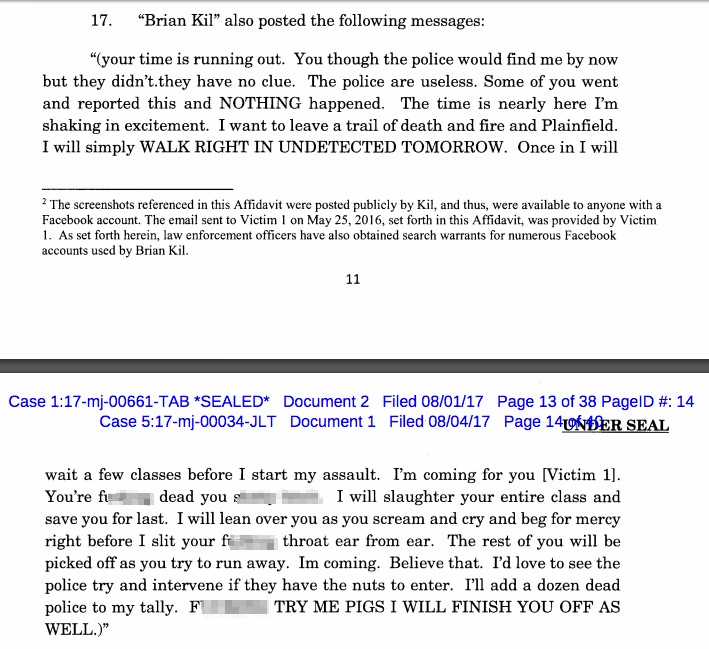

This is the type of threat that sextortionist “Brian Kil” posted publicly to Facebook, directed at one of many underage girls he victimized, along with sexually explicit photos he coerced out of them:

(Source: Criminal complaint)

In December 2015, “Brian Kil” went on to list the bombs and guns he purportedly had in his possession and with which he threatened to slaughter all of the students at one victim’s high school, saving her for last. The cyberthreats he made against that particular victim went on for 16 months.

Fortunately, in spite of hiding his identity and location behind Tor, he was wrong about the police not having a clue. Ultimately, they had much more than a clue: they had his IP address, secured through a booby-trapped video that the FBI had presented to him as being a sexually explicit recording.

On Monday, the US attorney’s office for the Southern District of Indiana announced charges against Buster Hernandez, 26, of Bakersfield, California. He’s suspected of using the alias “Brian Kil” and has been charged with threats to use an explosive device and sexual exploitation of a child.

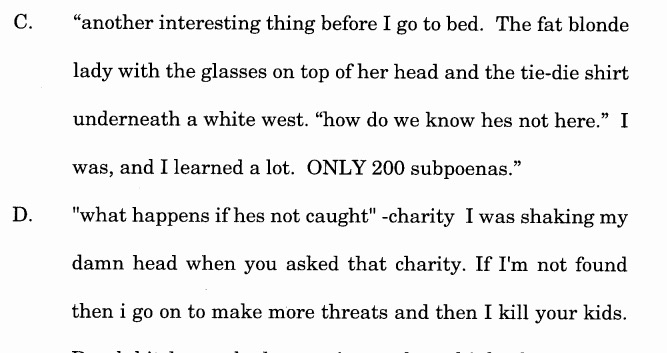

In December 2015, multiple high schools and shops in the towns of Plainville and Danville, Indiana, were shut down due to Kil’s terrorist threats. The following month, the community, along with police, held a forum to discuss the threats.

After the forum, Kil posted notes about who attended, what they wore, and what was said, as reported to him by a victim whom he’d coerced into attending and reporting back to him.

(Source: Criminal complaint)

Kil might well have been “lmfao” over the idea of ever being caught, but he wouldn’t be for much longer. Six months later, on June 7 2017, a judge authorized the FBI to use an NIT: a Network Investigative Technique

NIT, also known as police malware, is the bureau’s blanket term for malware that forces suspects’ devices to cough up their IP addresses. The FBI infamously used the technique in its Playpen operation, an investigation into child abuse imagery being shared via Tor that resulted in nearly 900 arrests worldwide.

How many of the Playpen prosecutions will end in conviction is an unanswered question. The question of whether the NIT warrant was constitutional is still playing out and has been deemed unconstitutional in at least one trial.

Playpen was a dark web site dedicated to child sex abuse. After finding Playpen’s original operator, the FBI took over the site and ran it for 13 days, from February 20 to March 4 2014. During that time, the FBI served up illegal child abuse imagery and planted an NIT on to more than 8,000 computers. Besides coughing up their IP addresses, the NIT also snagged the devices’ MAC addresses; open ports; lists of running programs; operating system types, versions and serial numbers; preferred browsers and versions; registered owners and registered company names; current logged-in user names; and their last-visited URL.

The case against Hernandez shows that the FBI’s spyware can also be targeted against individuals.

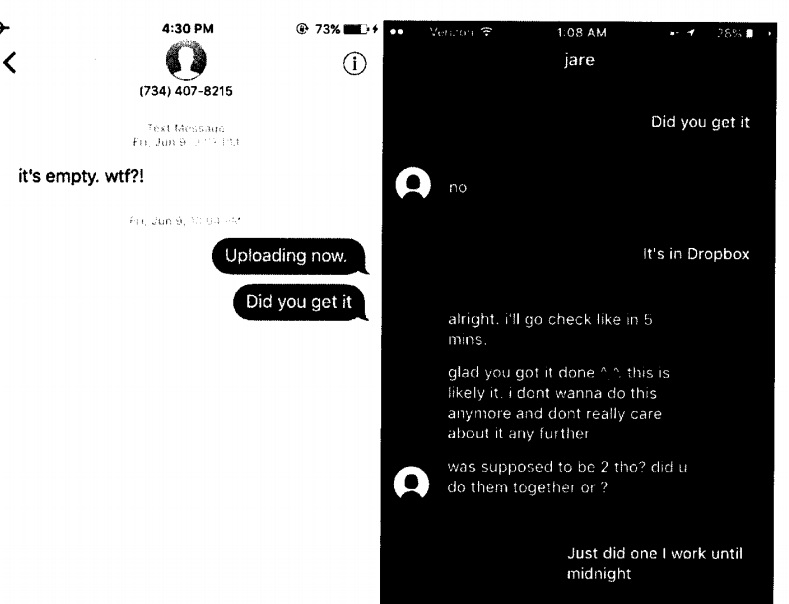

As the criminal complaint describes, after getting court authorization, the FBI inserted “a small piece of code” into a normal video file created by one of Kil’s victims. Unlike the illegal child abuse materials the FBI served up when it was running Playpen, this time around, the video wasn’t sexually explicit.

Agents them uploaded the file to Kil’s Dropbox account per his instruction and messaged him — at a voice over IP (VoIP) phone number that obscured the subscriber’s identity—to let him know.

(Source: Criminal Complaint)

Kil fell for it. After he opened the video, the NIT siphoned his IP address. The FBI set up a surveillance camera at the associated residence (Hernandez lives at the address with his girlfriend and her grandmother). They believe that Hernandez was the only one at home during the times that Tor was activated.

According prosecutor Tiffany J. Preston, Hernandez faces a mandatory minimum sentence of 15 years’ imprisonment, and a maximum of 30 years’ imprisonment if convicted on all counts, though maximum sentences are rarely carried out.

In his boastful posts, Kil admitted to lying. He couldn’t resist explaining how he got to Victim 1 in the first place, though, and it sounds plausible, given what we know about how sextortionists work.

Namely, and please do bear in mind that this is testimony from an admitted liar, he describes randomly targeting Victim 1 and doing research on her online posts, trying to find nude or sexually explicit images she may have shared. He admits to coming up short: the girl must have been listening to good advice about not sharing explicit images online.

But what she did share was videos of her dance routines. Somebody would film her, Kil says, and then she’d view and delete them.

At least, she thought she was deleting them, but in fact, they were still being stored in iCloud. Kil describes cracking her iCloud password and stealing the videos, which he then excerpted and doctored to make it appear that she was nude.

Sextortionists have in the past cracked victims’ accounts by sending them phishing emails that lead to sites where their login credentials are harvested. It was the modus operandi in the spate of celebrity photo thefts known as Celebgate, in fact. In June 2016, one of the Celebgate hackers pleaded guilty to phishing iCloud and Google logins as a means of getting his hands on his victims’ nude photos and videos.

This is why we believe in using multifactor authentication (MFA), also known as two-factor authentication, (2FA), whenever possible. Even if crooks crack your password, 2FA presents another big hurdle they have to leap before they can get into your accounts and steal your stuff. To read more about the hows and whys of 2FA, check out our Power of Two post.

Of course, teaching children not to share explicit material is crucial. So is encouraging them to report sextortionist or other cyberthreats, regardless of whether they’ve shared explicit material or not, as soon as possible.

The faster police know about these people , the faster their keyboards can be yanked out of their hands, and the lesser the damage they can inflict.

Leave a Reply