Britain’s vast, revered but increasingly troubled National Health Service (NHS) has many challenges to overcome but the one that is starting to really worry some sages is the way it uses – or more often fails to use securely – new technology.

As if a reminder of this perennial worry were needed, this week sees the publication of the first annual review from the Independent Review Panel, a body set up last year by Google’s DeepMind Health (DMH) unit to report on the company’s early work in the NHS.

Not unexpectedly, it reckons that the NHS and its modernisers have a big job on their hands. Writes Dr Julian Huppert, chair of the Independent Review Panel:

Many of the data systems in UK hospitals are still paper-based. They are complex, unwieldy and insecure, and the data they contain is difficult to manage.

It doesn’t help that the average NHS Trust must manage 160 IT systems to do its job, the result of a technological sprawl built over many decades.

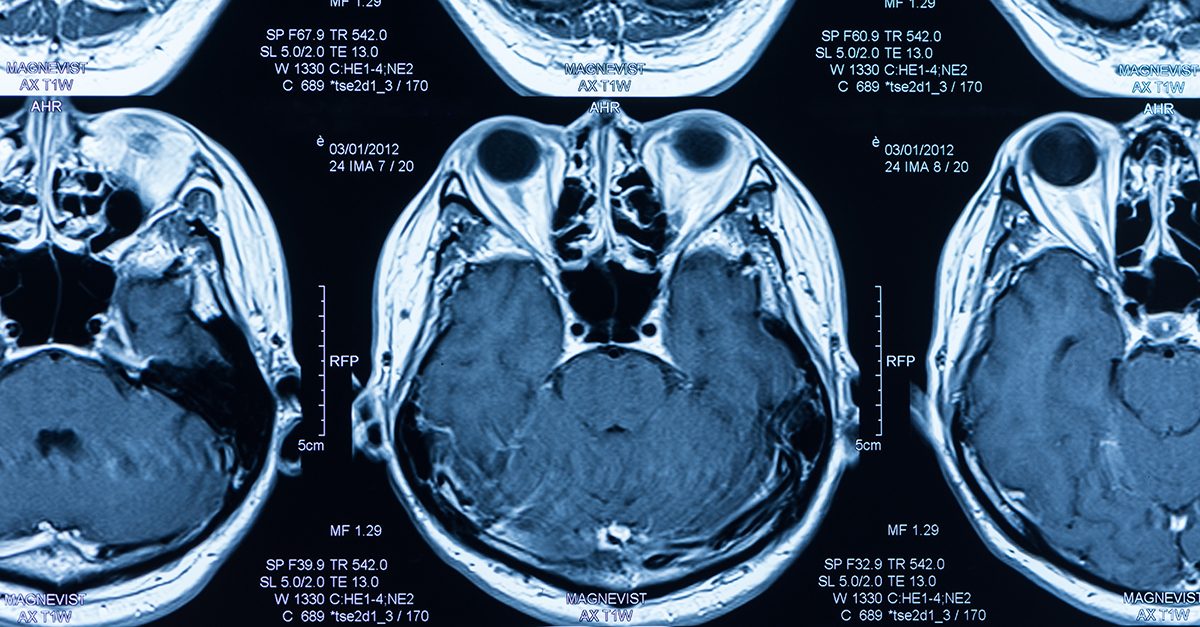

Then Huppert throws out more alarming discoveries, including that doctors have taken to using SnapChat “to send scans from one clinician to another or camera apps to record particular details of patient information in a convenient format”.

This is called “shadow IT”, something organisations have been struggling with for years. Then again, not every large organisation handles data as sensitive as medical scans using an app built primarily for teens wanting to share selfies.

By the time Huppert informs us that the NHS is the largest purchaser of fax machines in the world, the dream of a 21st century health service starts to like a distant prospect. Frankly, if this is true, it sounds more like a colossal museum.

Then it occurs to you that perhaps the problem isn’t that doctors are using SnapChat, but that they are having to do it unofficially. Arguably, embracing an app to transfer data would be fine as long as it could do so in a way that met security, privacy and regulatory requirements.

This brings us, inevitably, to DMH itself – it set up the Independent Review Panel that is telling us all of this after all.

On the score, the report’s appearance this week is either very good or very bad timing, depending on how you interpret the spanking handed out only days ago by the Information Commissioner (ICO) over a project DMH ran with London’s Royal Free NHS Trust from 2015 onwards to set up a kidney-monitoring app called Streams.

We’ll refrain from rehashing the infringements of the Data Protection Act (DPA) the project was found to have made, but note that while the judgement was aimed at the NHS Trust involved, DeepMind Health didn’t emerge unscathed either.

But aren’t apps like Streams – custom-developed by clever Google people – precisely the innovation the NHS needs a good dose of if it is to modernise?

According to the Independent Review Panel (which wrote its report before the ICO judgment and is not paid for its work), it most certainly is, although the panel isn’t afraid to criticise DMH in other respects.

Ironically, its biggest worry isn’t that Streams and its ilk will fail, but that they will succeed so well they will create complex problems the NHS is ill-equipped to deal with, such as increased demand as a result of earlier detection of medical conditions.

One way or another, the NHS will have to find a way to clear out the old and introduce the new without losing sight of its duty of care by developing a new culture of oversight that is still poorly understood. Enthusiasm alone won’t be enough – and neither will reports.

skolvikings

Let me get this straight… one of the problems this technology could bring is that, due to earlier diagnosis, more people would seek medical treatment? At a stage in their diseases where treatment is bound to be less expensive and more effective, but it’s more bodies seeking appointments, so that’s bad? Universal healthcare sure seems to have it’s fair share of cons.

Kate Bevan

Actually the evidence around screening and early detection is in general pretty equivocal: there is some evidence that PSA screening as a marker for prostate cancer isn’t a lifesaver and can in fact cause harm. Ditto concerns around screening for breast cancer. So yes, it can be problematic to be aiming for “earlier diagnosis” because it’s not necessarily the best way to spend the money. I recommend Margaret McCartney’s book, The Patient Paradox, if you’re interested in an accessible, lively and evidence-based discussion of that. http://www.pinterandmartin.com/the-patient-paradox.html

Universal healthcare can address this kind of thing at a population level, which is one of the many benefits of it.

Max

How can earlier diagnosis of anything possibly cause more harm than not knowing? It’s one thing if the early detection methods are flawed and give you a wrong diagnosis. But to generalize that into “early diagnosis might be a bad thing” seems a bit far reaching. It’s the detection methods that might be problematic, not trying to detect early. Of course it isn’t gonna help anyone if a psychic tells me I will get cancer in three months and I act on it like it’s a fact. But if there is a legitimate test that can help diagnose a disease in early stages with low enough false positives, we should definitely pursue those tests. And refine those that aren’t good enough yet.

Paul Ducklin

If you’re going to collect data about me, from me, that could lead to someone making an inference (and, let’s be honest without ourselves here, the words “early diagnosis” can often be converted into “a vague guess based on currently trendy research topics”) about my likelihood of getting X disease or Y condition or Z lifestyle problem in P months or Q years…

…then *you owe it to me* to ensure that the decisions made about me, and even perhaps for me, on the basis of those inferences are controlled, fair, reasonable and made only with my knowledge and consent. And the more you collect, and the more extensively you share it (even if your intentions are to improve my health), and the more unsuitable the techniques you choose for sharing it, the more likely it is that data and the “diagnoses” that are teased out of it will lead to egregiously unfair outcomes that I cannot control.

I’m thinking about stuff like altered job prospects, access to insurance, access to future health care, standing in the community and much more.

Max

Well, I think there is a significant difference between personal early diagnosis (with some error margin) and mass predicting possible diseases for collectives based on a data dump. And I think it are two separate issues, one is a question about how effective early detection of a disease is and the other one is if medical data should be shared freely. The second issue gets a clear “no”, regardless of how early a disease was detected. And that’s really the only issue that affects what you describe. A diagnosis should never affect the things you said (other than the disease physically making you unable to work certain jobs, that can’t be avoided), regardless of how early you get it. If it does, the early detection wasn’t the problem.

Kate Bevan

There’s a lot of discussion around this, and it’s a much more nuanced thing than we might imagine. It’s one of those times when the evidence provides an answer that’s really counter-intuitive. It absolutely sounds as if we should detect all cancer early, right? But that’s not the case in a number of types of cancer. One area is screening for prostate cancer, which is discussed in this BMJ piece http://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.f2232

Similarly, while there are often calls to screen young women for cervical cancer, you are more likely to cause harm than to save lives because young women’s cervixes (cervices??) change a lot, and you’re more likely to get a false positive as cervical cancer is very rare in young women. A positive test – which is very likely to be a false positive in a young woman of, say, under 25 – means a great deal of anxiety, not to mention further invasive tests and money spent on those tests, which in the UK where we have universal healthcare, is not a good way to spend resources. And all of those are harms.

I don’t have the figures to hand, but we screen vastly more people than cancers we catch. It’s not necessarily the case that screening saves lives, too: of course it does in some cases, but in many others, it simply identifies you as a cancer patient a bit earlier and doesn’t improve outcomes.

It’s a fascinating topic, and one I really recommend you read up on if you’re interested in how data often tell us things we didn’t expect to hear.

Max

I don’t have access to the whole article you linked, and the part I can access doesn’t say *why* the harms of a PSA outweight the benefits for most men, or what those harms are. Well, with your cervical cancer example I think we need to define harm, and how often false positives really occur as opposed to true positives, and how much of a difference it makes to detect cervical cancer early. If there are mostly false positives, and even the true positives don’t get any real benefit out of the early detection, then I agree with you. But if there is a significant amount of true positives whose lives can potentially be saved because of it, the benefits already outweigh the harm in my eyes. I think a certain amount of people experiencing “a great deal of anxiety” over a period of time is an acceptable price if in return we get to save other peoples lives because of it. But as I said in my earlier comment, it all depends. If if doesn’t make a difference how early you detect a disease, there is no point in screening for it on a broad scale. And if we don’t have a screening method that is precise enough to not give a majority of false positives, there isn’t much point either. But from my understanding there are a lot of diseases (especially forms of cancer) where knowing just a bit earlier can make all the difference. So we should focus to improve the screening methods for those specific diseases.

4caster

Several of the above comments seem to be along the lines of “Better use slow communication methods like snailmail because they provide an inbuilt delay during which the facts may change”. The implication is that clinicians believe early diagnosis often leads to early but inappropriate treatment.