In September, a home in Ohio caught fire, sending flames shooting into the sky, according to a neighbor.

Make sure the homeowner’s out of there, the emergency operator told the neighbor. But they didn’t need to worry: Ross Compton, the 59-year-old homeowner and now the alleged arsonist, had walked the driveway, safe and sound.

He told authorities that he’d packed a suitcase and some bags, broken a window with his cane and made his escape, climbing through the window and carrying the heavy bags to his car.

Quite a feat for a guy with extensive medical problems who’s got an artificial heart implant, investigators mused. Something about his story just didn’t add up. Actually, quite a few things didn’t: fire investigators said the fire was started in multiple places on the outside of the house, according to the search warrant.

Plus, in his call to emergency services, Compton said at one point that “everyone” was out of the house… and then, at the end of the call, told someone to “get out of here now”. Oh, and there was gasoline found on his clothing.

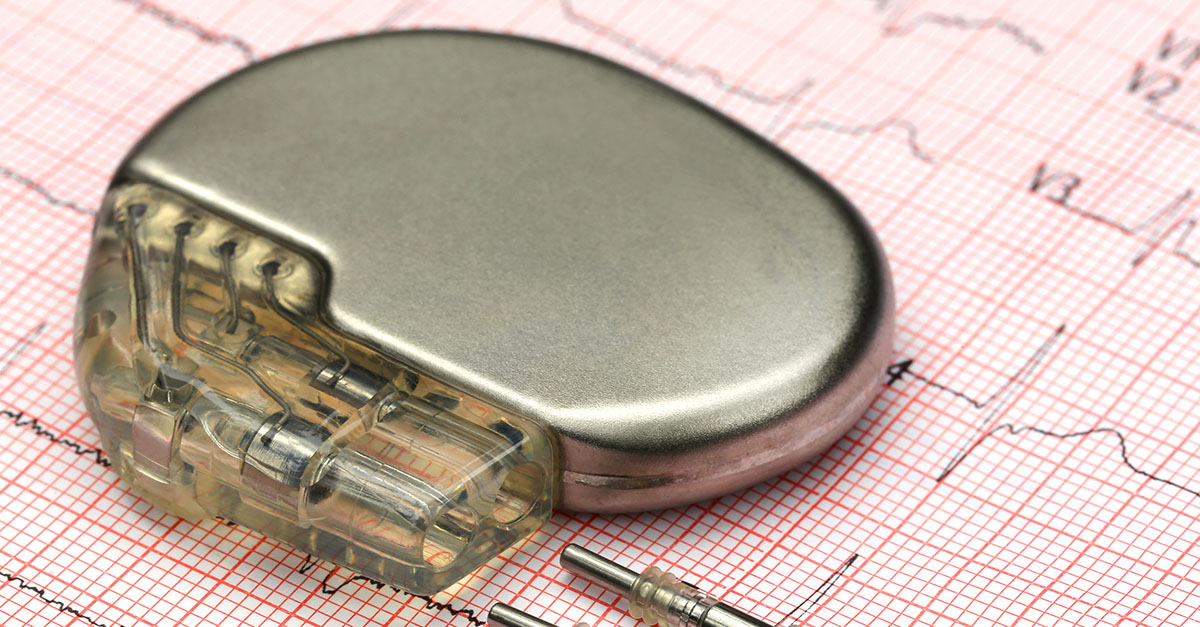

But about that pacemaker. According to court records seen by the local paper Journal News, police got a search warrant for all the data stored in the medical device.

The device yielded details of Compton’s heart rate, pacer demand and cardiac rhythms prior to, during and after the fire, and the story that data told was a very different one than Compton had come up with.

A month after the fire – estimated to have caused $400,000 in damage to the house and to have killed a pet cat – Compton was arrested and charged with felony aggravated arson and insurance fraud. He was indicted last week.

According to court documents, a cardiologist who reviewed the pacemaker’s data determined that it was…

…highly improbable Mr Compton would have been able to collect, pack and remove the number of items from the house, exit his bedroom window and carry numerous large and heavy items to the front of his residence during the short period of time he has indicated due to his medical conditions.

While this might be the first case of pacemaker data being used in a prosecution, it’s not the first use of Internet of Things (IoT) data being sought in a criminal investigation.

In December, Arkansas police were trying to get Amazon to help them get data from an Amazon Echo they found at a murder scene after a man was strangled in a hot tub.

Besides prosecutors and local police, the government is also quite interested in the information they can siphon from connected medical devices… and appliances… and toys… and, well, any and all data that can be monitored and collected courtesy of the IoT.

A year ago, the nation’s top spook – US director of national intelligence James Clapper – told the Senate that Big Brother might someday eyeball us through our world of connected gadgets, be they pacemakers, fridges, or toothbrushes.

In the future, intelligence services might use the [IoT] for identification, surveillance, monitoring, location tracking, and targeting for recruitment, or to gain access to networks or user credentials.

If and when intelligence agencies get around to tapping into the IoT – Clapper didn’t specify which specific agencies were mulling the move – they’ll have quite a list of household objects to squeeze surveillance out of. It probably won’t be too challenging to do so, given the security holes they’re known for.

We’ve seen issues with connected pacemakers, kettles, TVs, lightbulbs, thermostats, refrigerators and baby monitors that have all been designed without adherence to the information security principle of least privilege.

Of course, one person’s security hole is another person’s opportunity to gather evidence. Today, that means an Ohio court has sought, and received, pacemaker data that played some part in indicting an alleged arsonist.

Tomorrow, who knows which intelligence or law agencies will be using that information, and to what end?

All the more reason to know the risks of Amazon Alexa, Google Home, babycams, pacemakers and the whole lot of connected gadgetry.

This stuff increasingly proliferates in our homes. In the case of cardiac wireless devices, they’re implanted into our very bodies. It behooves us all to bear in mind that connected things, which can be our near-constant companions, can also be used as constant spying devices by hackers or as constant court recorders in potential criminal cases.

Remember, you have the right to remain silent, whether you’re being arrested and questioned by police or you decide to turn off Alexa’s always-on listening function.

For better or worse, your pacemaker does not.

Wilderness

What, no charges added on for animal cruelty for burning the cat?

Bryan

I’m a dog guy myself…and this was what I scanned the list of charges looking for.

:-)