Thanks to James Wyke of SophosLabs for doing the hard parts of this article.

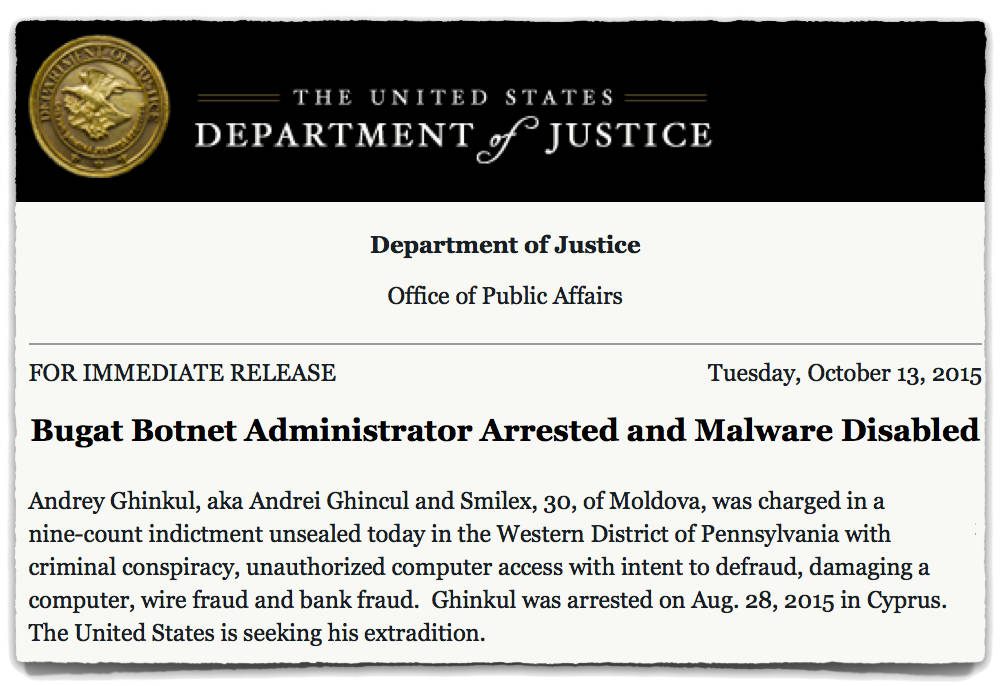

The US Department of Justice (DoJ) has just announced the disruption of an active botnet and the arrest of its alleged operator.

A botnet, as you probably know, is a “robot network” – a collection of computers in homes and offices around the world that are infected by malware that allows an operator, known as the botherder, to take control of those zombie computers from afar.

And a takedown is when law enforcement, often with the assistance of ISPs and security researchers, infiltrates the botnet in order to reduce the harm it can do.

In most takedowns, the network part of the botnet is disrupted so that the individual zombies no longer call home to the crooks for instructions, thus shielding potential victims from harm.

A takedown may also provide useful insight into the size and behaviour of a botnet, by capturing and analysing the messages coming from infected computers, as well as neutralising the botherder’s powers of remote control.

💡 LEARN MORE: Bots and zombies ►

The Smilex bust

In this latest takedown, the alleged botherder is Andrey Ghinkul, who also goes by the handle of Smilex.

Ghinkul was arrested in Cyprus on 28 August 2015, and now faces extradition to the US.

If he’s sent to America, he’ll face nine charges for a long list of offences: criminal conspiracy, unauthorized computer access with intent to defraud, damaging a computer, wire fraud and bank fraud.

Ghingul’s botnet, says the DoJ, was known as Bugat, though you will probably be more familiar with it by the family name Dridex.

We’ve written about Dridex before because the crooks behind it make extensive use of booby-trapped Word files as a vehicle to distribute the malware.

Instead of talking you into downloading and running unknown software from an unsolicited web link, the crooks send you a Word file and talk you into opening it.

That sounds fairly harmless, because Word files are supposed to contain data, not applications.

However, Word documents can contain embedded script programs known as macros that can sneakily download and run unknown software without asking you.

💡 LEARN MORE: Word macro malware ►

How Dridex infects

A typical Dridex infection progresses like this:

- An email attachment arrives with a plausible reason to open it. Common tactics are fake invoices and notices from courier companies. This email-based approach is particularly believable if you work in a small business that regularly processes orders and deals with collections and deliveries via email.

- The attachment asks you to enable Word macros, for example by claiming that the embedded macro scripts are needed if the file is to display properly. (Don’t do it! Macros are disabled by default in Word for good security reasons, notably to protect you from untrusted active content from outside.)

- The macros quietly download and run a program infected with the Dridex malware.

- Once activated, Dridex remains running in memory but removes itself from your hard disk and registry, thus making itself less obvious. Dridex survives reboots by sneakily saving itself back to disk as part of the shutdown process when you reboot or turn off your computer.

→ Ironically, a disorderly shutdown – such as tripping over the power cable of a desktop computer, or a software crash causing a Blue Screen of Death – may very well get rid of a Dridex infection. The malware either never receives a shutdown warning at all, or doesn’t have time to finish saving itself back to disk before the power goes off.

Making off with millions

Most Dridex malware samples are focused on bank fraud, and the botnet allegedly herded by Andrey Ghinkul was an example of just that.

According to the DoJ’s indictment, Ghinkul and his unnamed co-conspirators made off with millions of dollars, including some fraudulent transfers of alarmingly large amounts.

For example, Ghinkul’s crew allegedly netted $999,000 from a single school in Pennsylvania, and triggered two international transfers totalling more than $3.5 million from a Pennsylvania oil and gas company.

Dridex malware uses a combination of tricks to get banking credentials such as passwords and two-factor authentication codes into the hands of the crooks so they can plunder your accounts.

One trick is keylogging, where the malware monitors your typing and keeps track of your exact keystrokes at critical moments, such as when you are busy on a banking web page.

Another trick is web injects, where the malware modifies HTML or JavaScript code in key web pages as you browse, for example by adding fields into a web forms to lure you into revealing data that wouldn’t normally be required.

By messing with the content and appearance of web pages as you browse, cybercrooks may even be able to get past your two-factor authentication protection.

For example, if the crooks can grab your one-time code as soon as you type it in, they may be able to use it for a fraudulent transaction of their own, and then cover up any give-away errors or warnings that your bank might try to display in your browser.

💡 LEARN MORE: Two-factor authentication ►

Is that the end of Dridex?

Unfortunately, takedowns rarely kill off an entire botnet in one go.

Dridex, for example, is operated on what is effectively an affiliate model, where the criminals in control of the botnet as a whole lease out “sub-botnets” to other crooks, of which Ghinkul is alleged to have been one.

Unless two sub-botnets share the same botherder-to-botnet communication system, a takedown is likely to affect only one of them, in the same way that a even a blanket roadblock on the UK’s M40 motorway wouldn’t catch offending drivers on the nearby M25.

In any case, even when a major malware menace has been neutralised almost entirely in a takedown operation, other crooks will usually “fill the vacuum” by starting new but similar cybercrime operations.

We saw that happen in mid-2014, when a law enforcement operation aimed at disrupting the Gameover botnet also knocked out the servers behind the infamous CryptoLocker ransomware.

CryptoLocker would scramble your hard disk and demand money to decrypt it, but only after it had “called home” and been issued a unique encryption key tied to your computer.

In other words, disconnecting the core CryptoLocker servers had the happy side-effect of killing off that entire scam…

…but plenty of copycat cybercriminals rushed to fill the ransomware void left by the missing CryptoLocker infrastructure.

So don’t relax your guard!

💡 LEARN MORE: Dealing with ransomware ►

What to do?

- Use an anti-virus with an on-access scanner (also known as real time protection). This can help you block malware of this type in a multi-layered defence, e.g. by stopping the initial booby-trapped word file, preventing the Dridex download, blocking the downloaded malware from running, and finding and killing off the Dridex malware in memory.

- Beware of unsolicited and unusual attachments.

- Consider stricter email gateway settings. Some staff are more exposed to malware-sending crooks than others (e.g. the order processing department), and may benefit from more stringent precautions, rather than being inconvenienced by them.

- Consider using Microsoft’s dedicated Word and Excel viewer programs to look at email attachments. Most documents will display just fine, but embedded macros aren’t supported and thus cannot run.

- Never turn off security features because an email or document says so. Documents such as invoices, courier advisories and job applications should be legible without macros enabled.

💡 LEARN MORE: Avoiding email attacks ►

Note. Sophos products detect and remove the malware components described in this article under various names, including Troj/DocDl-* (the booby-trapped Word attachments that download the malware), Mal/Dridex-* and Troj/Dridex-* (the bank fraud malware program files), and Troj/DridxMem-A (when the malware is hiding in memory only).

Learn more about how cybercrime works

Listen to our Techknow podcast, Understanding Botnets. Learn, in plain English, the what, why and how of botnets – the money-making machinery of modern cybercrime.

![]()

(Audio player above not working for you? Download to listen offline, or listen on Soundcloud.)

Kill malware with the free Sophos Virus Removal Tool

This is a simple and straightforward tool for Windows users. It works alongside your existing anti-virus to find and get rid of any threats lurking on your computer.

Even if malware like Dridex is already running in memory, and has sneakily removed itself from disk, the Virus Removal Tool will find it and remove it for you.

Botnet image courtesy of Shutterstock.

Laurence Marks

Duck wrote “Consider using Microsoft’s dedicated Word and Excel viewer programs to look at email attachments. Most documents will display just fine, but embedded macros aren’t supported and thus cannot run.”

Good to see that you picked up on this. It’s even better to make the viewers the default for .doc, .docx, .xls, and .xlsx filetypes so you don’t accidentally slip.

Paul Ducklin

You mentioned the viewers last time we wrote about Word macros…and I was paying attention :-)

Anonymous

As usual, a snake-oil evangelist puts unreliable snake-oil as #1 on the to-do list.

What about SAFER alias software restriction policies?

Paul Ducklin

I am NOT an evangelist. I am a *proselytiser*, and my biography on THIS SITE says so. Please DO your RESEARCH before you start CASTING nasturtiums.

(Seriously: I can’t parse your second sentence, so I’m not sure quite what you are trying to say, beyond being uninventively rude.)