Thanks to James Wyke of SophosLabs for his help with this article, his expertise in dealing with botnets, and his ability to explain serious technical issues in a clear, crisp way. Love your work!

Interpol just announced another co-ordinated botnet takedown, hot on the heels of Europol’s action against the BeeBone malware.

Interpol just announced another co-ordinated botnet takedown, hot on the heels of Europol’s action against the BeeBone malware.

This time, the malware family in the takedown is called Simda, a threat first reported by SophosLabs back in 2011 that has now morphed into an extensive family of variants.

Simda hasn’t been high in the malware prevalence charts lately, but it has nevertheless been a clear and present danger.

In the Sophos Security Threat Report 2014, for example, we noted that Simda accounted for 2% of the malware distributed online via so-called exploit kits.

→ An exploit kit, or EK, is a bundle of malicious components, typically inserted by crooks into an innocent web server they’ve just hacked, that automates the distribution of malware. Usually, there’s an innocent looking HTML page that loads a malicious JavaScript file to work out your current combination of operating system, browser and plugins. The JavaScript then chooses a list of exploits (attacks) it thinks are likely to work, and lets rip with them in sequence, hoping to find a vulnerability you forgot to patch.

Simda, of course, being part of a botnet, is itself what’s known as a bot, or zombie malware.

Bot is short for “software robot,” and botnet is short for “a collection of software robots under the control of one cybercriminal group.” (The crook who gets the job of controlling a botnet is known as the bot herder, or botmaster.)

A bot is malware that not only sets directly about its dirty work, but also reaches out onto the internet to download instructions on what to do next.

Bots can also fetch updates or additional malware so they can mount attacks that weren’t programmed in from the start.

Think of it like Windows Update, but with exactly the opposite intent.

Instead of looking out for instructions from head office at Microsoft to download fixes or tighten security settings, a bot watches out for commands from the cyberunderworld ordering it to commit the next wave of cybercrime.

That’s the bad side of bots: they are flexible, adaptable tools for cybercrime.

It’s like a burglar in the physical world having a special sort of multitool that starts off with just a screwdriver and a blade, but can automatically acquire additional tools – bolt cutters, angle grinders, lockpicks, crowbars – whenever he wants, even when he’s in the middle of a job.

Indeed, according to James Wyke at SophosLabs, Simda has been used for a variety of “value-add” cybercrimes over the years.

It’s installed rootkits (malware-hiding malware) onto infected computers; watched out for banking transactions in order to steal login details; delivered malware for other crooks on a “pay-per-install” basis; and deliberately redirected web traffic away from sites like Facebook and Google Analytics towards imposter sites.

Simda has also reinforced itself with tricks deliberately designed to frustrate security researchers, as James explained in a paper presented at the Virus Bulletin 2014 conference.

The good side, at least from the law enforcement angle, is that bots need to get their instructions and their updates from somewhere.

Often, though not always, that means there is a nucleus of servers, controlled by the crooks, used for what’s called C&C, C2, or Command-and-Control.

If law enforcement can identify the location of one or more of those servers, then they can act.

Firstly, the servers can be replaced with ones that no longer issue malicious orders to the computers in the botnet, allowing law enforcement to identify victims (very useful in a prosecution), and even to reach out to them, for example via their ISP, to advise and assist them with cleanup.

Secondly, law enforcement can seize and analyse the malicious servers.

Sometimes, there’s double paydirt for the Good Guys on the confiscated servers, as when the Gameover botnet was taken down, and the cops found that the servers they’d nabbed contained the back-end system, including decryption keys, for the CryptoLocker malware.

It’s early days yet to say what extra paydirt Interpol and its partners in anti-crime might find from this latest Simda takedown.

But with C&C servers taken out in The Netherlands, US, Russia, Luxembourg and Poland, there are already two praiseworthy outcomes:

- Up to 770,000 computers disconnected from the crooks who had been controlling them.

- Yet another example that despite the complexities of law enforcement across multiple jurisdictions, law enforcement teams can and do work together effectively to counter global cybercrime.

Good work!

Learn more about botnets

Listen to our Techknow podcast entitled Understanding Botnets. Learn, in plain English, the what, why and how of bots, botnets and cybercrime.

![]()

(Audio player above not working for you? Download to listen offline, or listen on Soundcloud.)

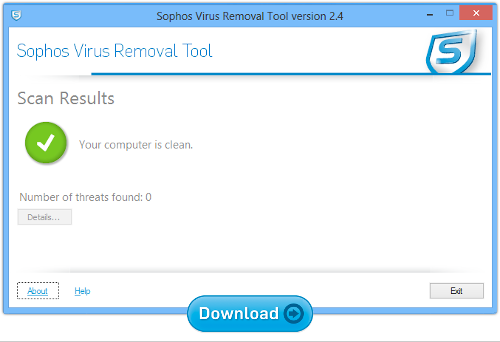

Free Virus Removal Tool

The Sophos Free Virus Removal Tool works alongside your existing anti-virus to find and get rid of any threats lurking on your computer.

Download and run it, wait for it to grab the very latest updates from Sophos, and then let it scan through memory and your hard disk. If it finds any threats, you can click a button to clean them up.

Leave a Reply