If you’d never heard the cybersecurity jargon word “juicejacking” until the last few days (or, indeed, if you’d never heard it at all until you opened this article), don’t get into a panic about it.

You’re not out of touch.

Here at Naked Security, we knew what it meant, not so much because it’s a clear and public danger, but because we remembered the word from a while ago… close to 12 years ago, in fact, when we first wrote up a series of tips about it:

Back in 2011, the term was (as far as we can tell) brand new, written variously as juice jacking, juice-jacking, and, correctly, in our opinion, simply as juicejacking, and was coined to describe a cyberattack technique that had just been demonstrated at the Black Hat 2011 conference in Las Vegas.

Juicejacking explained

The idea is simple: people on the road, especially at airports, where their own phone charger is either squashed away deep in their carry-on luggage and too troublesome to extract, or packed into the cargo hold of a plane where it can’t be accessed, often get struck by charge anxiety.

Phone charge anxiety, which first became a thing in the 1990s and 2000s, is the equivalent of electric vehicle range anxiety today, where you can’t resist plugging in for a bit more juice right now, even if you’ve only got a few minutes to spare, in case you hit a snag later on in your journey.

But phones charge over USB cables, which are specifically designed so they can carry both power and data.

So, if you plug your phone into a USB outlet that’s provided by someone else, how can you be sure that it’s only providing charging power, and not secretly trying to negotiate a data connection with your device at the same time?

What’s if there’s a computer at the other end that’s not only supplying 5 volts DC, but also sneakily trying to interact with your phone behind your back?

The simple answer is that you can’t be sure, especially if it’s 2011 and you’re at the Black Hat conference attending a talk entitled Mactans: Injecting malware into iOS devices via malicious chargers.

The word Mactans was meant to be a BWAIN, or Bug With An Impressive Name (it’s derived from the zoological name latrodectus mactans, the small but toxic black widow spider), but “juicejacking” was the nickname that stuck.

Interestingly, Apple responded to the juicejacking demo with a simple but effective change in iOS, which is pretty close to how iOS reacts today when it’s hooked up over USB to an as-yet-unknown device:

Android, too, doesn’t allow previously unseen computers to exchange files with your phone until you have agreed to do so via a menu setting on your device.

Is juicejacking still a thing?

In theory, then, you can’t easily get juicejacked any more, because both Apple and Google have adopted defaults that take the element of surprise out of the equation.

You could get tricked, or suckered, or cajoled, or whatever, into agreeing to trust a device you later wish you hadn’t…

…but, in theory at least, data grabbing can’t happen behind your back without you first seeing a visible request, and then replying to it yourself by tapping a button or choosing a menu option to enable it.

We were therefore a bit surprised to see both the US FCC (the Federal Communications Commission) and the FBI (the Federal Bureau of Investigation) publicly warning people in the last few days about the risks of juicejacking.

In the words of the FCC:

If your battery is running low, be aware that juicing up your electronic device at free USB port charging stations, such as those found in airports and hotel lobbies, might have unfortunate consequences. You could become a victim of “juice jacking,” yet another cyber-theft tactic.

Cybersecurity experts warn that bad actors can load malware onto public USB charging stations to maliciously access electronic devices while they are being charged. Malware installed through a corrupted USB port can lock a device or export personal data and passwords directly to the perpetrator. Criminals can then use that information to access online accounts or sell it to other bad actors.

And according to the FBI in Denver, Colorado:

Bad actors have figured out ways to use public USB ports to introduce malware and monitoring software onto devices.

How safe is the power supply?

Make no mistake, we’d advise you to use your own charger whenever you can, and not to rely on unknown USB connectors or cables, not least because you have no idea how safe or reliable the voltage converter in the charging circuit might be.

You don’t know whether you are going to get a well-regulated 5V DC, or a voltage spike that harms your device.

A destructive voltage could arrive by accident, for example due to a cheap-and-cheerful, non-safety-compliant charging circuit that saved a few cents on manufacturing costs by illegally failing to follow proper standards for keeping the mains parts and the low-voltage parts of the circuitry apart.

Or a rogue voltage spike could arrive on purpose.

Long-term Naked Security readers will remember a device that looked like a USB storage stick but was dubbed the USB Killer, which we wrote about back in 2017:

By using the modest USB voltage and current to charge a bank of capacitors hidden inside the device, it quickly reached the point at which it could release a 240V spike back into your laptop or phone, probably frying it (and perhaps giving you a nasty shock if you were holding or touching it at the time).

How safe is your data?

But what about the risks of getting your data slurped surreptitiously by a charger that also acted as a host computer and tried to take over control of your device without permission?

Do the security improvements introduced in the wake of the Mactans juicejacking tool back in 2011 still hold up?

We think they do, based on plugging an iPhone (iOS 16) and a Google Pixel (Android 13) into a Mac (macOS 13 Ventura) and a Windows 11 laptop (2022H2 build).

Firstly, neither phone would connect automatically to macOS or Windows when plugged in for the first time, whether locked or unlocked.

When plugging the iPhone into Windows 11, we were asked to approve the connection every time before we could view content via the laptop, which required the phone to be unlocked to get at the approval popup:

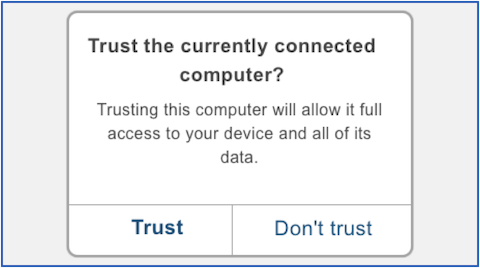

Plugging the iPhone into our Mac for the first time required us to agree to trust the computer at the other end, which obviously required unlocking the phone (though once we’d agreed to trust the Mac, the phone would immediately show up in the Mac’s Finder app when connected in future, even if it was locked at the time):

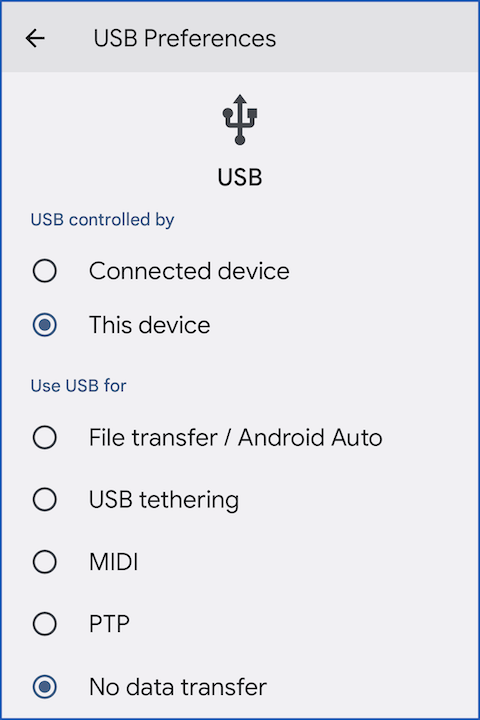

Our Google phone needed to be told to switch its USB connection out of No data mode every time we plugged it in, which meant opening the Settings app, which required the device to be unlocked first:

PTP mode pretends your phone is a camera and makes your images available. File Transfer provides more general access to files on the device.

The host computers could see that the phones were connected whenever they were plugged in, thus giving them access to the name of the device and various hardware identifiers, which is a small amount of data leakage you should be aware of, but the data on the phone itself was apparently off limits.

Our Google phone behaved the same way when plugged in for the second, third or subsequent time, identifying that there was a device connected, but automatically setting it into No data mode as shown above, making your files invisible by default both to macOS and to Windows.

Untrusting computers on your iPhone

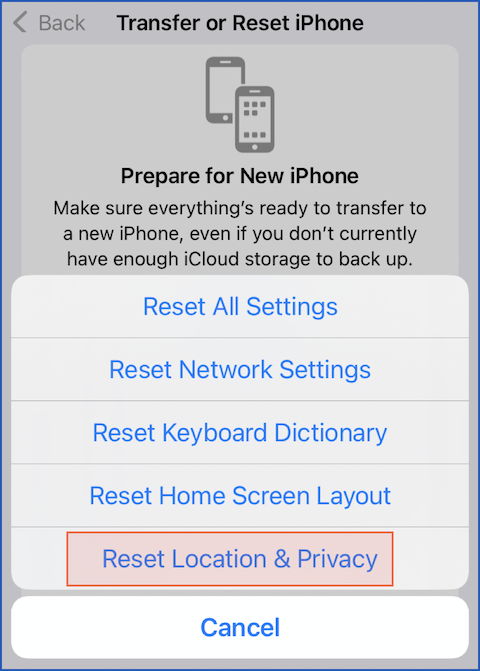

By the way, one annoying misfeature of iOS (we consider it a bug, but that is an opinion rather than a fact) is there is no menu in the iOS Settings app where you can view a list of computers you’ve previously trusted, and revoke trust for individual devices.

You’re expected to remember which computers you’ve trusted, and you can only revoke that trust in an all-or-nothing way.

To untrust any individual computer, you have to untrust them all, via the not-in-any-way-obvious and deeply nested Settings > General > Transfer or Reset iPhone > Reset Location & Privacy screen, under a misleading heading that suggests these options are only useful when you buy a new iPhone:

What to do?

- Avoid unknown charging connectors or cables if you can. Even a charging station set up in good faith might not have the electrical quality and voltage regulation you would like. Avoid cheap mains chargers, too, if you can. Bring a brand you trust along with you, or charge from your own laptop.

- Lock or turn off your phone before connecting it to a charger or computer. This minimises the risk of accidentally opening up files to a rogue charging station, and ensures that the device is locked if it gets grabbed and stolen at a multi-user charging unit.

- Consider untrusting all devices on your iPhone before risking an unknown computer or charger. This ensures there are no forgotten trusted devices you may have set up by mistake on a previous trip.

- Consider acquiring a power-only USB cable or adapter socket. “Dataless” USB-A plugs are easy to spot because they have only two metallic electrical connectors in their housing, at the outer edges of the socket, rather than four connectors across the width. Note that the inner connectors aren’t always immediately obvious because they don’t come right to the edge of the socket – that’s so the power connectors make contact first.

The pink rectangles indicate roughly where the data connectors would be.

NotConcerned

This article comes off a bit naive. Of course juice jacking isn’t some widespread problem but to discount any warning based on a very basic test of connecting phones to a windows PC and mac and getting a prompt is kind of silly. That doesn’t prove there aren’t methods with zero clicks/taps needed (pretty sure our gov has this(pegasus) and we all know how well they keep secrets. Besides any single click could easily be solved with minimal social engineering at the ‘bad’ charging station. “Make sure to allow SCAM Charger so you get highest charging speed”. The recent warnings make me wonder what agency fell for this

Paul Ducklin

If this genuinely “isn’t some widespread problem”, then the FCC is distracting people’s security attention by putting out a national warning about it. If you are prepared to allow zero-day/zero-click bugs and to assume social engineering attacks will inevitably succeed, then you should be warning people against using almost any browser, or any operating system, or clicking any button at any time.

The whole point of this article is to show the protections that are supposed to be in place (with screenshots and an explanation of why), to advise readers how to avoid any potential data leakage exploits that might be found in USB connection code (bring your own charger or get a power-only USB-A cable and relevant converter adapters), and to put the risk into perspective.

I don’t accept that I “discounted” the warning. I think we are providing usable, simple and effective advice… and it’s important not to suggest that specific security precautions deliver a higher degree of general safety than they really do. People love “quick fixes” because they feel useful even if their overall protection is slight, so they act as a kind of “I can do this easy thing and then I have an excuse for not doing this hard thing that is nevertheless much, much more important”.

Pete

According to slate, this was just someone reposting a 4 year old article without stating the source: https://slate.com/technology/2023/04/free-public-phone-chargers-fbi-warning-bad-actors-threat-bogus-debunked.html

Maybe you could check this legitimacy? Puts this whole “warning” into a different context.

Philip Le Riche

A few years ago I remember a Windows vulnerability (I think) in the USB ennumeration logic that could be triggered by a rogue device to get kernel-level code execution. Isn’t that just the sort of thing NSO Group or similar might well have researched and found, or a certain Far Eastern autocracy might develop for gaining access to the devices of foreign diplomats and business men in hotels and airport lounges? Perhaps this is real!

Paul Ducklin

It could be. But in a world where drive-by kernel exploits and web browser 0-days show up fairly regularly, and can only reliably be avoided by patches, at least this risk is easily circumvented (bring own charger). And if there is a current 0-day behind this, perhaps the FCC could have made that clear, rather than presenting it as a general, widespread, long-term risk to consumers everywhere. In short, don’t let this warning divert you from the many other, more productive, security precautions you can take. (Like patching promptly.)

Robin Stevens

At industry events it’s common for the vendor stands to be handing out all sorts of USB freebies, including power banks and charging cables. There have been some well-documented cases of malware being distributed on free USB memory sticks, but how concerned should one be about the other gadgetry? How well defended are desktop OSes against a rogue cable charging that suddenly starts generating malicious keystrokes?

Paul Ducklin

Ho hum… I was at one of the most famous “malware cocktail conferences” in Oz in 2010 – IBM was nominated for a Pwnie Award for this one:

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2010/05/21/ibm-distributes-usb-malware-cocktail-auscert-security-conference/

As for USB devices (or cables emanating from them) that pretend to be keyboards… those are hard to defend against right now because there’s no cryptographic security behind a device that claims to have ID X from vendor Y with feature set Z to filter on.

(In fact, mainstream security devices like Yubikeys can run in “fake keyboard” mode to help you enter complex secrets without needing special drivers.)

Best bet IMO is as mentioned in the article: bring own charger and cable; ensure device is locked (so rogue keystrokes couldn’t trigger commands); consider getting it making a power-only cable and don’t rely on a random one at the airport…

Anonymous

Besides generating keystrokes, wasn’t there some case of USB devices with malicious firmware that OSes just trusted and ran as soon as plugged in? (Maybe my memory is wrong?) Are OSes any better protected against this sort of threat today?

And also other peripherals (like SD card) I wonder are they more/less/same level of threat as USB devices?

Paul Ducklin

A few years ago (in the mid-to-late 2010s) there were several Thunderbolt-related firmware treacheries with names like ‘Thunderclap’, ‘Thunderspy’ and, most dramatically of all, ‘Thunderstrike’. (It’s lightning that strikes, but never mind that for now.)

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2015/01/09/thunderstrike-new-mac-ueberrootkit-could-own-your-apple-forever

The Thunderstrike attack, from memory, could be done by boot-trapping an Apple ethernet adaptor (this was back when Thunderbolt used Display Port connectors; today’s it’s USB-C based).

Apple fixed this PDQ, as I recall, and it only applied to Macs, not to iPhones or iPads.

As for SD cards… do any modern phones still bother with SD sockets? I don’t think I’ve had a phone with a card slot for several years (saves a bit of space and money)… and SIM slots are on the way out, too.

john shale

I was thinking “just use your own charger” but what if your phone charger has memory and bluetooth capability, when you buy it? At Governmental level, this could be an innocuous plant..

Paul Ducklin

Nothing is impossible (“never say never”) but some risks are obscure enough that you need to accept them. (Every electronic component in your computer, phone, kettle, TV, automobile, heck, even your battery operated bicycle lights, could somehow be booby trapped.)

.

You said everything regarding the reality of these warnings from both the FCC and the FBI, said this: “distracting people’s security attention by putting out a national warning”… Distracting everyone’s attention from all the negative situations both of those agencies have placed themselves in, by trying to put out some information about something that they’re doing to help you. Unfortunately they’re not even doing that, as you pointed out it’s old and basically useless information…

Rene Kunz

Hope all manufacturers will soon use MagSafe chargers and thus increase safety for everyone.

Paul Ducklin

MagSafe is proprietary to Apple, and is designed for charging laptops that have separate data ports.

No phone vendor (not even Apple) is going to introduce a bulky MagSafe charging connector onto the side of their phones… too big, and anyway the new regulated standard for phone charging is USB-C.

(I have never understood the fascination with MagSafe myself. I had one MagSafe Mac in my life and I went through three chargers in the laptop’s life – the magnets fade and the cables fray. Since then I have acquired three Apple USB-C chargers and they all still work just fine.)

Anonymous

Sorry if you’ve never heard of:

The MagSafe Charger makes wireless charging a snap. The perfectly aligned magnets attach to your iPhone 14, iPhone 14 Pro, iPhone 13, iPhone 13 Pro, iPhone 12, and iPhone 12 Pro and provide faster wireless charging up to 15W.

II believe I have already read that other smartphone manufacturers will also use this charging technology.

Paul Ducklin

Ah, MagSafe has turned into a generic term… used to be the, ahem, magnetic connector on the side of Macs only.

Nigel Smith

Even Wireless Chargers aren’t perfect, as we have seen NFC Vulnerabilities on Android and iOS. If you are close enough for a Magsafe/Qi charger to work, you are close enough for an NFC Connection as well. Alot of people leave NFC on all the time, so Wireless Chargers could still be an attack vector.

Some articles from Sophos about NFC attacks:

How to steal money via Apple Pay using the “Express Transit” feature – Paul Ducklin

Google patches bug that let nearby hackers send malware to your phone – Danny Bradbury

Black Hat – Don’t stand so close to me: An analysis of the NFC attack surface – Chester Wisniewski

eDubya

Today, I had a Door to door salesman ask to borrow a charging brick. Not thinking about it, I let him, social engineered. He sat on my porch by the outlet for 30 minutes or so. I assume it is possible he uploaded malware to my charging brick. Any way to test? More curious than anything, it’s one of many bricks I have so I don’t have any issue tossing it.

Paul Ducklin

If all it does is supply power, and it isn’t also a storage device (hard disk) then I think it is safe to say that the answer is “No”.

Juicejacking involves a rogue “charging brick” (that is secretly more than just a charger) trying to attack a smart device that’s plugged into it.