If you’re a gamer or an avid squeezer of raw computing power, you’ve probably spent hours tweaking your motherboard settings to eke out every last drop of performance.

Over the years, you might even have tried out various unofficial firmware bodges and hacks to let you change settings that would otherwise be inaccessible, or to choose configuration combinations that aren’t usually allowed.

Just to be clear: we strongly advise against installing unknown, untrusted firmware BLOBs.

(BLOB is a jocular jargon term for firmware files that’s short for binary large object, meaning that it’s an all-in-one stew of code, tables of data, embedded files and images, and indeed anything needed by the firmware when it starts up.)

Loosely speaking, the firmware is a kind of low-level operating system in its own right that is responsible for getting your computer to the point at which it can boot into a regular operating system such as Windows, or one of the BSDs, or a Linux distro.

This means that booby-trapped firmware code, if you can be tricked into installing it, could be used to undermine the very security on which your subsequent operating system security relies.

Rogue firmware could, in theory, be used to spy on almost everything you do on your computer, acting as a super-low-level rootkit, the jargon term for malware that exists primarily to protect and hide other malware.

Rootkits generally aim to make higher-level malware difficult not only to remove, but even to detect in the first place.

The word rootkit comes from the old days of Unix hacking, before PCs themselves existed, let alone PC viruses and other malware. It referred to what was essentially a rogueware toolkit that users with unauthorised sysadmin privileges, also known as root access, could install to evade detection. Rootkit components often includes modified ls, ps and rm system commands, for example (list files, list processes and remove files respectively), that deliberately suppressed mention of the intruder’s rogue software, and refused to delete it even if asked to do so. The name derives from the concept of “a software kit to help hackers and crackers maintain root access even after they’re being hunted down by the system’s real sysadmins”.

Digital signatures considered helpful

These days, rogue firmware downloads are generally easier to spot than they were in the past, given that they are usually digitally signed by the official vendor.

These digital signatures can either be verified by the existing firmware to prevent rogue updates being installed at all (depending on your motherboard and its current configuration), or verified on another computer to check that they have the imprimatur of the vendor.

Note that digital signatures give you a much stronger proof of legitimacy than download checksums such as SHA-256 file hashes that are published on a company’s download site.

A download checksum simply confirms that the raw content of the file you downloaded matches the copy of the file on the site, thus providing a quick way of verifying that there were no network errors during the download.

If crooks hack the server to alter the file you are going to download, they can simply alter its listed checksum at the same time, and the two will match, because there is no cryptographic secret involved in calculating the checksum from the file.

Digital signatures, however, are tied to a so-called private key that the vendor can store separately from the website, and the digital signature is typically calculated and added to the file somewhere in the vendor’s own, supposedly secure, software build system.

That way, the signed file retains its signed digital label wherever it goes.

So, even if crooks manage to create a booby-trapped download file, they can’t create a digital signature that reliably identifies them as the vendor you’d expect to see as the creator the file.

Unless, of course, the crooks manage to steal the vendor’s private keys used for creating those digital signatures…

…which is a bit like getting hold of a medieval monarch’s signet ring, so you can imprint their personal mark into the wax seals on totally fraudulent documents.

MSI’s dilemma

Well, fans of MSI motherboards should be doubly cautious of installing off-market firmware right now, apparently even if it apparently comes with a legitimate-looking MSI digital “seal of approval”.

The motherboard megacorp issued an official breach notification at the end of last week, admitting:

MSI recently suffered a cyberattack on part of its information systems. […] Currently, the affected systems have gradually resumed normal operations, with no significant impact on financial business.

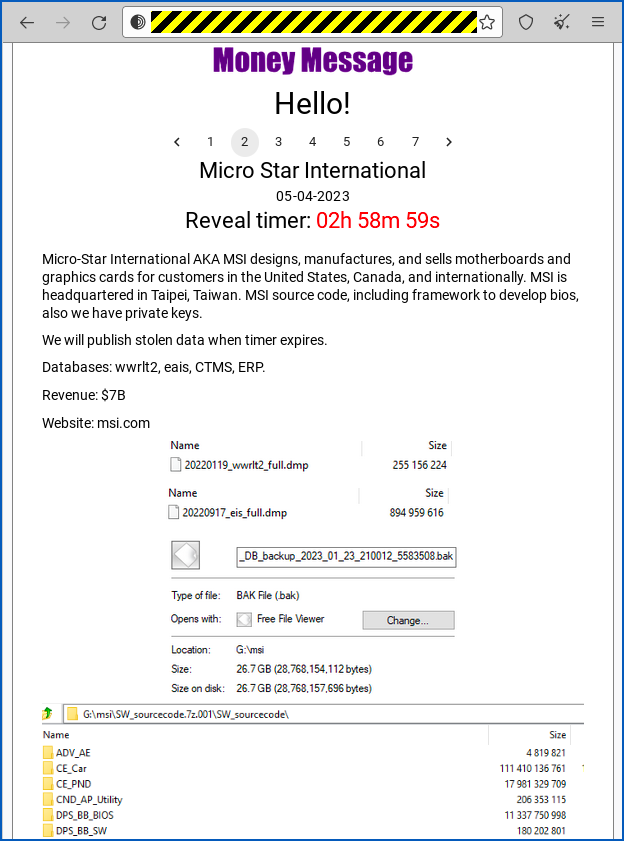

Word on the street is that MSI was hit by a ransomware gang going by the in-your-face name of Money Message, who are apparently attempting to blackmail MSI by threatening, amongst other nastinesses, to expose stolen data such as:

MSI source code including framework to develop BIOS [sic], also we have private keys.

The implication seems to be that the criminals now have the wherewithal to build a firmware BLOB not only in the right format but also with the right digital signature embedded in it.

MSI has neither confirmed nor denied what was stolen, but is warning customers “to obtain firmware/BIOS updates only from [MSI’s] official website, and not to use files from sources other than the official website.”

What to do?

If the criminals are telling the truth, and they really do have the private keys they need to sign firmware BLOBs…

…then going off-market is now doubly dangerous, because checking the digital signature of the downloaded file is no longer enough to confirm its origin.

Carefully sticking to MSI’s official site is safer, because the crooks would need not only the signing keys for the firmware file, but also a login to the official site to replace the genuine download with their booby-trapped fake.

We’re hoping that MSI is taking extra care over who has access to its official download portal right now, and watching it more carefully than usual for unexpected changes…

Peter

Could MSI not revoke the certificate that was used to sign the files so even if someone did download a file that had been compromised it would then fail the certificate check or does it not work like that?

Paul Ducklin

One problem with instantly blocking all items already signed with key X is that you might end up blocking vital components that are already installed but haven’t been updated to their digitally-re-signed equivalents.

(You can simulate this for yourself by going into your BIOS and deleting the securely-stored public keys that vouch for the files that are used in the course of Secure Boot to get from the “post-firmware” stage of booting up to the “operating system safely loaded” stage. If you then immediately restart your computer, it will refuse to boot because the Secure Boot files will no longer be considered secure. PS. DON’T DO THIS :-)

Kind of like locking your keys inside the car, but quite possibly with no windows you can smash ([:drum emoji:][:cymbal emoji:]) and fix later to get temporary access as a workaround.

Pete

Nice analogy with locking the keys inside the car.

I once did the opposite: Put the backpack with the company laptop and car keys outside the car and then decided to move the car forward a little to prevent other cars damaging it. When I closed the door the car realised that the keys are outside so the owner apparently wants to walk away, so it locked the door. Gives you a nice rush of adrenaline in the middle of the night. Was able to attract a cyclist with my flashing lights who decided to not run away with my backpack but to put it closer to the car so I could get out.

I wasn’t aware how to open the locked car from within. Having a tested business continuity plan for this situation would have reduced the stress significantly.

Paul Ducklin

Ah, for the good old days when there was a lever on the inside of the door that opened it regardless of the lockedness of the, er, lock.

(On early Minis there wasn’t even a lever, just a bit of string – OK, wire – that you pulled on to unlatch the door.)

Mahhn

If you ever get stuck in this situation again (won’t happen but) as this has to be a modern car (keyless entry) you can exit out the trunk/boot, seats fold down or open and all modern cars have an open option lever/cable. Take a look next time you have it open.

Paul Ducklin

I’m sorry, Pete, I’m afraid I can’t do that.

This mission is much too important for me to allow you to jeopardise it.

Anonymous

So what you’re saying is you can use the boot as a backdoor?

Paul Ducklin

[:Drum emoji:][:Cymbal emoji:]

…also, due to the fact the a boot lid opens in a different plane to a car door, you can’t stand upright when using it… you have to move laterally.

Anonymous

Besides the problems mentioned by Duck, I assume that end user software might not check revocation status of certificates in time to catch this, so certificate revocation is not a magic bullet. Depends on how end user software is configured and how vigilant the end user is.

Paul Ducklin

And if third-party security software *does* notice the revoked certificate before the system itself does… what should it do? Ignore? Warn? Or intervene by forcing a power-down? (Same thing for signed drivers, signed OS files, signed files for key software apps in use, and much more.)

DN

How much do we have to worry now about buying MSI motherboards from a third party that may or may not have a compromised BIOS and what could we do about it?

Paul Ducklin

I assume you could flash a known-good image acquired directly from MSI… any MSI tweaking fans care to comment?

PI

Personally, I don’t consider the security risk to be a major concern since Windows requires firmware to be signed for Microsoft.

Anonymous

> Just to be clear: we strongly advise against installing unknown, untrusted firmware BLOBs.

Most firmware BLOBs you find on devices everywhere today can’t really be trusted even if they are “known” since the majority of them are closed source. They could be running any kind of evil code on your system and you wouldn’t know it.

Paul Ducklin

At least there’s a modest amount of accountability (or at least traceability) for a BLOB that’s signed by the vendor…

…as for closed versus open source, a significant proportion of devices (I am including routers, doorbells, any and all sorts of “smart” devices here) run on open source, notably based on the Linux kernel and userland code published under “must reveal your source code” licensing conditions.

But that only means that anyone can peruse the code if they want (including attackers, of course), assuming the vendor complies with the letter of the licence. The fact that you may and can study the source code doesn’t mean that anyone has actually done so.

Ironically, strict checking of digital certificates by the locked-down core firmware in a device often undermines one of the original goals of GPL-type licensing (“you can change it if you want”) because you probably can’t. You are still dependent not only on Good People finding the security holes before the crooks do, but also on Responsive Vendors bothering to fix them.

But I take your point. What firmware is baked into your CPU itself? Your mobile phone network modem (the “baseband”)? What closed source magic sauce is layered on top of the open-source kernel (as in both iOS and most Android distros, including Google’s own)? Nevertheless… I would be wary of random BLOBs, as tempting as they can be, especially for older Android phones that can easily be reflashed but aren’t getting official updates any more.

Anon

If it a Qualcomm or Broadcom chip powering it, it’s not usually fully open source unfortunately. Those are firmware blobs that keep you from fully completely changing, controlling, or upgrading the device even if you can break into it and gain root access. Though, regardless, it is fun to play around once you’re in. Even modifying and adding onto what’s already there could open up a ton of possibilities.

It could even force a device to work with open standards and disable calling-home and close externally accessible insecure access.