This morning, Sophos published a report about a relatively small player in the ransomware space. The ransomware, called Matrix, doesn’t produce the high returns of the better-known SamSam (whose creators were indicted by US law enfocement authorities last fall), and it doesn’t have the “get rich quick” spin of the better known GandCrab ransomware-as-a-service. What it does demonstrate, however, is that a small team of malware developers and attackers can successfully leverage the low hanging fruit of Remote Desktop to breach networks and cause damage and mayhem.

You can download the report now; Analysts may wish to retrieve our list of Matrix ransomware IoCs they can use for threat hunting in their environment. Our friends at Naked Security have also published a story about Matrix.

Matrix is a curious case, because while its creators clearly understand the principles involved in creating a ransomware Trojan, their creation demonstrates a mix of differing levels of competencies in carrying out attacks. Unlike its more high-profile brethren, Matrix has not adopted techniques that would permit it to spread widely inside networks, where machines vulnerable to wormable exploits (like EternalBlue) might be running. But the constant level of improvement indicates that may not remain the case forever.

The biggest problem Matrix highlights is that, despite the wide publicity that SamSam, Ryuk, and other targeted ransomware have gained, large enterprise networks still rely on security by obscurity, and permit Windows computers with passwords of dubious strength to be exposed to the unfiltered internet, where they can be attacked from outside with impunity. These machines then can become a foothold to the attacker, who can use it to target bigger fish inside the firewall.

Post attack interaction

In its earliest incarnations, Matrix curiously attempted to replicate an earlier generation of ransomware. The now-abandoned ransom note claimed that the ransomware originated with law enforcement, a practice that hasn’t been used for many years. The more recent versions of the malware now have given up this pretense and simply make demands.

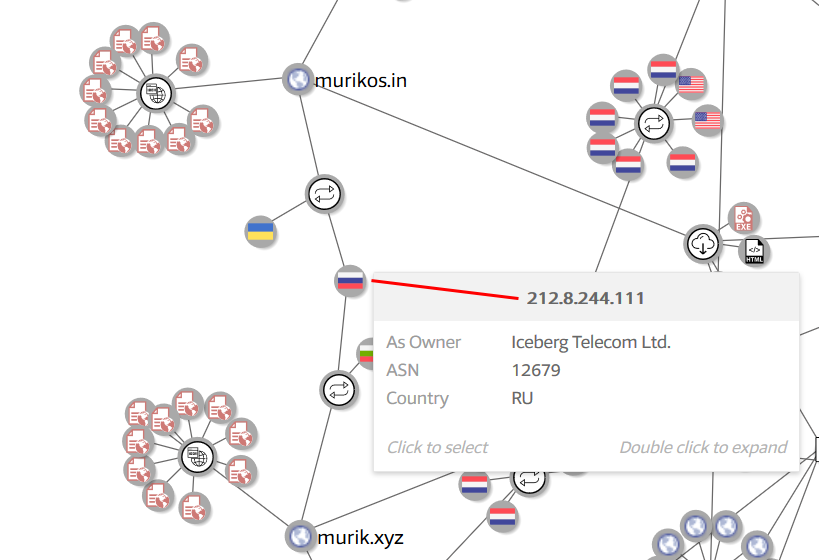

The malware authors ask the victims to contact them for the ransom amount, so it’s unknown at this time how much they’ve earned. We do know, however, that for much of the time that Matrix existed, its attackers had a preferred method of contact which is now unavailable to them: A niche private messaging service called bitmsg.me used to afford them some measure of privacy, but after that service shut down last month, the attackers fell back on using email accounts on free webmail services exclusively.

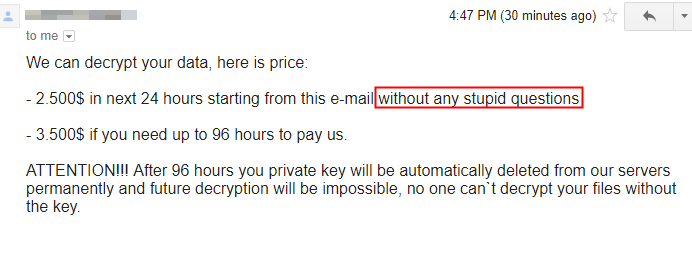

After running a sample in a test environment, research analyst and reverse engineer Luca Nagy, the report’s author and the primary investigator for this project, contacted the attackers at the email addresses they provided. The attackers demanded $2500 initially, and threatened to raise the ransom to $3500 if the payment wasn’t received right away, or (notably) if the victim asked “stupid questions.”

After Luca failed to respond to emails for several days, the attackers emailed back, offering her a discount price of $1000 if she still wanted to decrypt her files.

Technical capabilities

The Matrix ransomware package has a huge resource section; Its creators have embedded the kitchen sink of what it might need in these resources: instructions, tools, and documents like the ransom note. The resource section also contains some of the cryptographic keys that are used during the malicious encryption phase of the attack. Importantly, the creators have engaged in the questionable application of cryptographic principles, using the same, hardcoded string as both the key and as a nonce in the encryption algorithm.

Also included in the resource section are several components of what more competent ransomware creators have built into their competing malware: There’s a priority list of file extensions targeted for attack, another list of filesystem paths and files to be excluded, and a check to make sure the ransomware doesn’t accidentally run on a machine that is being used in Russia or any of several former-Soviet republics, based on the language settings of the operating system. Unfortunately for the attackers, that means all it takes to prevent the malware from running is to set a system preference to the Kazakh language, for instance.

The malware’s creators also wanted to try to evade detection by endpoint antivirus products, so they eventually also added an exclusion list that prevents the malware from encrypting anything in a folder named SOPHOS (or named after any of several other AV products). The law of unintended consequences rules here: if you put your documents in a folder named after any of these companies, Matrix won’t encrypt them.

After the malicious encryption is complete, the malware invokes one of the resources it has embedded — a Windows shell .cmd file — to securely wipe deleted, unencrypted files.

The .cmd file uses a standard Windows executable called cipher.exe to do this. Windows uses cipher.exe to manage encrypted files on NTFS partitions, but it isn’t always needed. A Group Policy rule that restricts the situations in which cipher.exe can be invoked would, at the very least, give an incident responder a chance to recover the unencrypted files marked as deleted from the hard drive.

But despite these many shortcomings, it’s not fair to say the ransomware isn’t harmful. It is capable of doing damage to infected computers; Its only truly saving grace is that the ransomware isn’t effective at spreading itself around rapidly.

It doesn’t hurt matters that Sophos products are able to detect its presence during the earliest stages of infection, when the malware hasn’t yet had a chance to do any real damage, but the fact that it takes some manual effort for the attackers to get Matrix onto each computer does limit its effectiveness.

But the thing that would eliminate its effectiveness: Systems administrators need to block all direct access to Windows machines whose RDP is accessible through the firewall (no matter which port is it running on), and instead require users who need to remotely access their computers connect to a VPN to do so.