You read a ton of articles nagging you about your passwords, most particularly in these iPhone-been-BUSTED! days.

They’ve got to have uppercase letters, lowercase letters, numbers, weird symbols, flanges, Rustoleum, and should optimally be double-jointed… or something like that.

You’ve got a strong password. At least you think you’ve got a strong password, but how to know for sure? You could run it through a password strength-o-matic meter!

What could possibly go wrong?

That’s what Adrienne Porter Felt from the Google Chrome security team asked on Tuesday, when she came across a CNBC article about password security that asked users to type in their passwords to check how secure they were:

- Using a plain old unencrypted HTTP connection

- that inadvertently shared passwords with advertisers

- and stored them in a Google spreadsheet.

Unimpressed security and privacy researcher Ashkan Soltani, tweeted a screenshot of CNBC’s password profligacy.

Holy crap: @cnbc now sends your test passwd to all 3rd parties when you hit enter @__apf__https://t.co/rOQuvJ4KE2 pic.twitter.com/diRjcvJ919

— ashkan soltani (@ashk4n) March 29, 2016

According to PC World’s Jeremy Kirk, copies of the passwords went to companies including Google’s DoubleClick advertising service and Scorecard Research, an online marketing company that’s part of comScore.

And that bit about the meter not storing passwords: according to Kane York, who works on the Let’s Encrypt project, traffic analysis showed the tool was actually storing the passwords in a Google Docs spreadsheet.

.@__apf__ @CNBC The “Submit” button loads your password into a @googledocs spreadsheet!

— Kaney (@riking27) March 29, 2016

Hmmm… that’s sure not what the password strength meter said. It was labelled like so:

This tool is for entertainment and educational purposes only. No passwords are being stored.

What could possibly go wrong, indeed!

The CNBC story that included the password strength meter, “Apple and the construction of secure passwords,” was initially posted on CNBC’s blog The Big Crunch on Tuesday but has since been removed.

THIS is what could possibly go wrong

CNBC’s intentions were good: to teach people the importance of a strong, unique password, but getting it right is harder than it looks.

Good password strength meters, such as the highly rated zxcvbn used by Dropbox and WordPress, test your password using client-side code that runs entirely in your browser so the password being tested doesn’t leave your device.

The strength meter used by CNBC apparently used server-side code though, which meant that passwords were sent over the internet to a server and the results sent back.

Private data like passwords should always be sent over the web using HTTPS, the encrypted form of HTTP, so that you know where it’s being sent and that it isn’t compromised on the way.

The CNBC article sent passwords “in the clear,” leaving them open to interception and manipulation.

Even with an HTTPS connection server-side checking is still a bad idea though; the passwords might travel to their destination safely but you’ll never know what happens to them when they get there.

CNBC made things worse by sending unencrypted passwords to their server as a parameter in the page’s URL, which meant that anything else that the URL was shared with, such as 3rd party advertisers and web analytics providers, got a copy of the password being tested too.

The passwords may also have ended up being stored in HTTP log files on the destination server too.

And finally, even if you find yourself using a password strength meter that gets everything right and doesn’t send your password anywhere, you should apply a heavy dose of salt to anything it tells you about your password.

As Naked Security’s Mark Stockley has noted, you can’t trust those things.

There are other ways to be sure that you’re generating strong passwords. Here’s a video on how to pick a proper one:

→ Can’t view the video on this page? Watch directly from YouTube. Can’t hear the audio? Click on the Captions icon for closed captions.

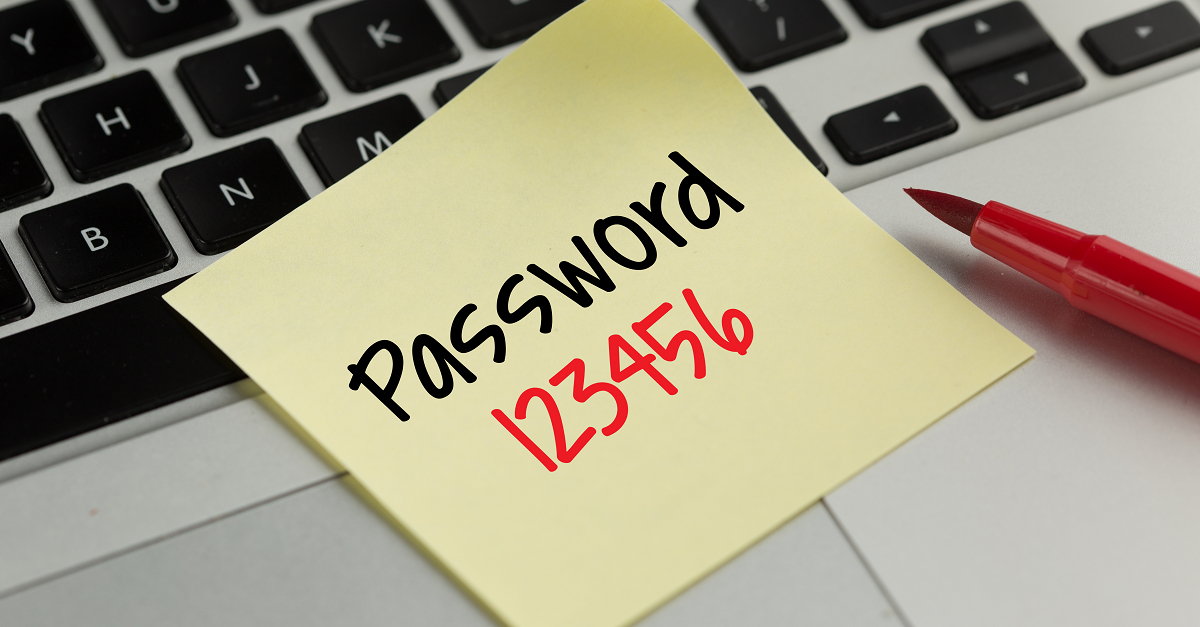

Image of Easy password courtesy of Shutterstock.com

Mahhn

LOL

Steve

More like COL… C for Crying.

Anonymous

I seem to remember a naked security article about the same thing that had a link to a password strength checking site… I think it was passfault?

BigRed64

At last count I have 24-logins & passwords (mostly for business); at least I know where the Post-it notes are where I have recorded them all. :)

Claudia

Better make sure that those post-it-notes are never in view of your webcam! ;-)