A surveillance specialist’s LinkedIn profile said that at his penultimate job in this line of work, he:

A surveillance specialist’s LinkedIn profile said that at his penultimate job in this line of work, he:

Lobbied for independent review of collection management processes and redefined mission, scope and daily duties.

He only lasted two months. After a final two-month stint at another gig, and after a career that spanned 22 years, he left the intelligence community altogether and went to work selling used cars.

Had he been trying to change the surveillance industry from within? Was he stonewalled? Is that why he left his last two positions after such brief times, and then walked away from the industry?

We don’t know.

But the analyst’s story, as told through his LinkedIn profile, presents an example of how open source intelligence, Google search, and search terms associated with surveillance activities and tools can be used to put a human face on the surveillance state.

Putting that human face onto headline-grabbing, Snowden-era revelations about surveillance is the reason why an organisation called Transparency Toolkit has created a searchable database of the resumes and details of 27,000 people working in the intelligence community, mostly in the US.

The researchers drew on LinkedIn and similar sites where the staff openly share information about their jobs.

Transparency Toolkit founder M.C. McGrath earlier this week unveiled the “prototype” online database, called ICWatch, at the re:publica conference on the internet and society in Berlin.

Here’s what McGrath says is the thinking behind creating the database:

Institutions are made up of people. And when we can understand what people do within institutions, why they do it, what their world view is, [and] how they got to that point, we can get a better understanding of how they function [and] how we can reform them. Luckily, it's very easy to find out who's involved in the surveillance state with just a few simple Google searches.

It’s easy because people need jobs, McGrath said, whether they’re leaving the military, working for the National Security Agency (NSA) or other intelligence outfits, or employed by military contractors.

And when you need a job, you need to post about what you can do.

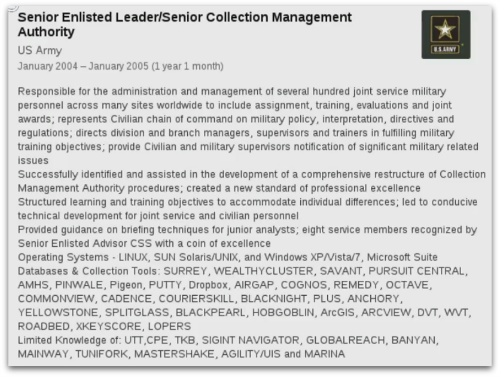

And what you can do, when you’re working in intel, includes things like intercepting communications and using secret surveillance databases and analytics tools.

That means that people post things like “I know how to use XKeyscore” and other secret tools, right up there with boasting that they know how to use Microsoft Word, he said.

By comparing shared skill sets and the program names mentioned by analysts in their online resumes, Transparency Toolkit has already been able to draw inferences about programs not seen outside of the profiles.

That includes the discovery of new code words, not previously seen outside of previously published NSA documents.

Some of the discoveries so far, for example, have included a collection tool called Pursuit Central; the new code words include PENNANTRACE, DISPLAYVIEW and CEGS, used for identifying, collecting and performing direction finding of specified target signals, according to surveillance specialists’ resumes.

By cross-referencing the various job descriptions, Transparency Toolkit has been able to figure out that those code words are concerned with geolocational data – specifically, airborne SIGINT (signals intelligence) platforms, which leads the researchers to conclude that the code words are potentially associated with surveillance of drones.

Transparency Toolkit researchers have already been able to glean broad trends, including the dropoff in people working in the field of SIGINT around 2013, as determined by the dropping rate of returns on the use of the search term “SIGINT“: a trend that correlates to the time when Edward Snowden first began to unleash revelations, thereby potentially suggesting a “Snowden Effect” on surveillance industry employment.

Or, at least, it points to people’s ebbing willingness to use intel-related keywords when filling in their LinkedIn profiles.

The information McGrath collated is all available in the public domain, highlighting the need to lock down your privacy settings on LinkedIn and other platforms that carry personal information about you that you might not want shared with the world in an easily searchable format.

This database isn’t meant to pull together a hit list, McGrath stressed.

It’s running on a data set that’s got some noise, for one thing. Some people who’ve worked as contractors had job roles unrelated to surveillance, for example.

But even those people in the database who are definitely working in surveillance aren’t necessarily horrible people, McGrath said, and we shouldn’t demonize them.

The purpose of the database, he said, is to put a face on the surveillance state, but it’s also meant to start debates.

People might, for example, question why some companies are hiring for things that sound sketchy, McGrath suggested, or even start conversations with those people who are involved in intelligence activities.

Take that guy who went on to sell cars, he said:

It's possible he got frustrated with some of the processes. It's hard to know. It's a good reminder that not necessarily everyone on this list is a bad person who is doing horrible things. Some people are probably trying to change the system from within, and we don't necessarily know it.

Image of surveillance worker courtesy of Shutterstock.