Larry Tesler, the computer scientist who is widely credited with the copy-and-paste function that is now nearly ubiquitous in user interfaces, has died at 74.

Tesler – note the spelling! – worked at the influential Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, better known as PARC, in the 1970s.

Old-timers in the computer industry will tell you that “everything that we take for granted in computing these days was invented at PARC”, and there’s a grain of truth in that rose-tinted reminiscence.

Xerox, so the story goes, was worried that the paperless office was on its way, which wouldn’t be great for its vast photocopier business.

If everyone in an office had their own computer, companies wouldn’t need copiers because they could share documents electronically, and if they did need a printed copy, then they could just print it out themselves.

At least, they could do those things if [a] they had their own computers, [b] those computers were easy to use, the computers could be interconnected reliably, [d] the computers could be programmed easily, and [e] if they had printers that were kind of like copiers, but didn’t need an original document to copy from.

So the researchers at PARC came up with, and learned to program and use, a whole raft of technologies that we do now take for granted – such as ethernet networking, object-oriented programming, laser printers, personal computers, bitmapped screens (so you could do text and graphics at the same time, just like in a book), square pixels, GUIs, a mouse to control them, and, of course…

…copy-and-paste.

Steve Jobs visited PARC in the 1970s, and by 1983, Apple had come out with a personal computer called Macintosh that had a bitmapped screen, square pixels, a GUI, a mouse to control it and, of course… copy-and-paste. By 1985, Apple had followed up with the Laserwriter, an astonishingly powerful personal printer with more memory and a more powerful processor than the Macintosh itself.

In fact, Larry Tesler’s ideas about user interface design went much deeper than just copy-and-paste.

He lived by the computer science motto No Modes.

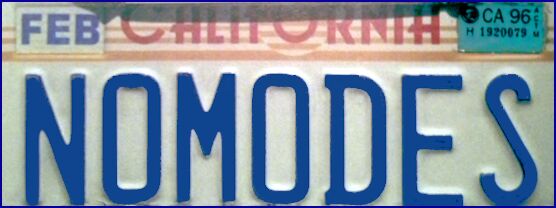

His car tag and his personal website both featured the text NOMODES – which, in computing terms, means that things such as mouse clicks and keypresses should work consistently, rather than changing what they mean and do as you navigate through a program.

You wouldn’t tolerate a keyboard where A came out as B, B as C, and so on, but only when you were in the menu to pick a new font – it wouldn’t just be annoying, it would be confusing and error-prone.

You wouldn’t be safe driving a car where the brake and clutch pedals swapped over when you entered a private car park, only to swap over again when you exited back onto a public road.

Why modes?

So why, Tesler wanted to know, do we have so much computer software where keystrokes and mouse clicks change their meaning depending on where you are in the program?

The classic example of a “modal program” is the famous vi editor, where characters sometimes stand for themselves, and sometimes stand for controls to choose an operating mode.

For instance, if you are in the middle of a file, editing it with vi, and you want to add the word riddle into the document, you might think you’d just click where you wanted the text and then type r – i – d – d – l – e.

Riddle-me, riddle-me, riddle-me-ree, but that’s not how it works.

Ther enters replace mode, which says to overwrite the current character with the next one you type, namely i.

Then the first d in riddle enters delete mode, and the d after that is a delete-mode operator that says to delete the entire line, ironically including the i character you just entered into the text in the wrong place.

Now you are automatically back in command mode, where l says to move the cursor right (don’t shoot us, we’re just the messenger), and the final e moves to the end of the current word.

Phew!

To enter riddle into the document itself you have to type i – r – i – d – d – l – e – Esc, which first turns on insert mode, then inputs the actual characters you want, and finally escapes from insert mode back to command mode.

You can see why Larry Tesler was passionate about NOMODES.

Even if there are still millions of vi-loving techies and programmers who don’t yet agree with him.

Larry Tesler, RIP.

Latest Naked Security podcast

LISTEN NOW

Click-and-drag on the soundwaves below to skip to any point in the podcast. You can also listen directly on Soundcloud.

Featured picture of Larry Tesler smiling cropped from CC-BY-2.0 image via Flickr.

Name

RIP

Larry Marks

I didn’t know Larry, but I guarantee you I won’t miss vi. Not one bit. EDLIN, on the other hand, still has a place in my heart, as does the TSO mainframe line editor.

Anonymous

I do get the point here – but I love vi and still use it.

Paul Ducklin

Secretly, I do too. (Elvis is my vi variant of choice.) At the same time I often wonder how many working hours have gone down the toilet over the years thanks to vi’s modal cantankerousness. Because when vi is annoying it is *properly* and uncompromisingly annoying!

Where vi really used to shine, and its cryptic modality actually worked in its favour, was on slow serial lines, say 300 or 1200 bits/sec, where every keystroke could be made to count. Commands like “cw” to change the next word simplified screen updates and made everything smoother and faster to use, albeit at the cost of being cryptic to learn. But you only needed to learn once.

Still…

…NOMODES is a great philosophy, even if you have a special place in your life for one of the vi family. Just think how confusing it is these days when, say, Ctrl-C/Ctrl-V (or Wacky-C/Wacky-V on a Mac) *doesn’t* do copy and paste, such as when you are in most terminal programs and you have to remember to use Ctrl-Alt-C (urxvt) or Shift-Ctrl-C (most others) and the related -V command instead.

ZZ

Bryan

I’m with anon and Paul in loving vi my variant of choice being vim. Although it’s admittedly been so long I no longer recall what features supersede its predecessor. Nonetheless I dutifully install it each time I build a new workstation or server †

Every now and then I trip over another feature heretofore unknown; it was only last year I learned how handy zz can be.

:,)

When I was young and green, a grizzled and sagely DB admin tried to initiate me into the Cult Of Emacs, briefly administering a tutorial he doubtless was unaware made a whirlwind of my brain. I’d been learning vi for maybe a couple weeks from other teammates, and I think he meant well, hoping to “save” me–it didn’t take.

I was so inexperienced I required eight or ten months to understand why many coworkers held him in such high esteem. Not that I doubted them–it’s just that I still needed to learn enough to learn. Good ol’ Phil.

† overheard everywhere, for millennia:

But why do we do it this way?

Because that’s how we’ve always done it.