Well-known cybersecurity journalist Brian Krebs is reporting a US scam aimed at chip-based payment cards.

The crooks are stealing cards before they reach their intended recipients – an old technique for credit card fraud, admittedly, but now with an added twist.

These days, just stealing a new card in transit often won’t work, because the crooks don’t have the information needed to activate the new card…

…but in this scam, the crooks have figured out a way to do an end run around the activation process: steal just the chip off the card, and wait for the legitimate recipient to activate the card.

Assuming the recipient doesn’t spot the tampering, of course.

How the crime works

According to the US Secret Service, the government law enforcement agency that deals, amongst other things, with postal fraud, the crime goes something like this:

- Intercept cards on the way to corporate recipients. We’re not sure whether corporates are targeted because they have more money, because they tend to receive cards in easily-detectable batches, or because their card usage patterns mean that scammed cards generally take longer to get spotted.

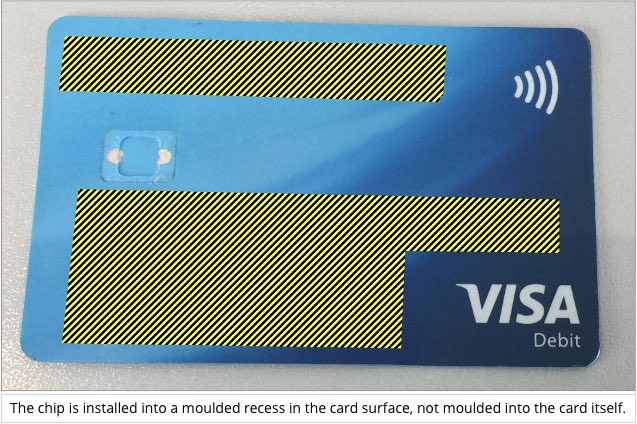

- Prise the chips out of the cards.

- Glue old chips from expired cards into the holes left by the real chips. The replacement chips don’t need to work – they merely need to look OK to disguise the fact that the cards have been tampered with.

- Send the original cards onwards to the intended recipients.

- Wait for the recipients to activate the modified cards.

- Spend, spend, spend using the stolen chips glued onto fake blank cards. This works either until the card issuers spot irregularities in the transactions being processed, or until the cardholders try to do chip transactions themselves, realise their new cards have a dud chips, and report the problem.

What to do?

As far as we can see, this sort of scam would be harder to pull off outside the US, where chip transactions require a PIN as well as the chip.

Banks in some countries still insist on sending out both new cards and PINs by snail mail, which is insecure for recipients who live or work in apartment or office blocks with a shared mailbox area, but the crooks would nevertheless need to intercept both the cards and their matching PIN mailers to be able to use the stolen chips.

Chips aren’t hard to remove, however – here’s a video of us doing it using just a hairdryer and a pair of tweezers:

What to do?

Here are some tips that will help if you are worried about chip-swap scams:

- Inspect the card mailer carefully. We assume that the crooks need accomplices inside the postal service who remove letters from the system so they can be opened, modified and re-sealed.

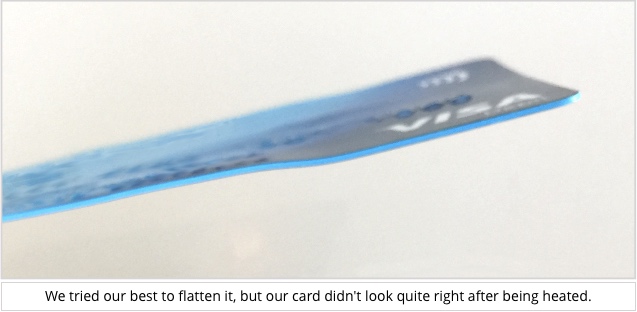

- Inspect the chip and the card carefully. It’s hard to remove the chip without leaving some signs of tampering, so look out for heat damage (the card plastic tends to wrinkle, bend and change colour easily) or scratches around the chip where the original was pried out.

- Take the card into your bank to activate it. That way the bank can verify whether the chip is valid or not before enabling it – activating online or over the phone works without validating the chip itself.

- If you can’t activate in the bank, do a small chip transaction immediately after activation. Do not swipe the card, because you are testing to see if the chip is dud or not. If it is, cancel the card at once.

Riggerrob

What if you (unknowingly) just swiped to make your first purchase, rather than using the chip portion?

Paul Ducklin

AFAIK, activating the card and doing legitimate transations via the magstripe can’t and won’t reactivate an implanted, expired chip that’s been glued onto your new card.

In other words, if the chip is dud, meaning that it’s been tampered with, you won’t be able to complete a chip transaction, so doing one and having it fail would be a good telltale of fraud. My suggestion of doing a chip transaction ASAP was simply that the sooner you know something is fishy, the quicker you can act…

John Morgus

Some of the new cards suggest activating by performing a transaction — even a balance inquiry will do. As Mr. Ducklin said — the dud chip would cause the transaction to fail. Also, with a warped card a chip may not even fit into the reader.

Paul Ducklin

We formed the opinion that with a bit of practice we could avoid warping the chip. But if the card were warped enough not to fit in the machine you ought to notice…

s7evep

If your final services provider uses a card reader for 2 factor access to online banking (eg Nationwide and Barclays in the UK) you can test the chip yourselves at home.

Paul Ducklin

Good point – I am not sure whether that sort of system exists in the US, however, because their credit card system is Chip and Nothing (OK, Chip and Signature, for what signing is worth), not Chip and PIN.

AFAIK, when our American colleagues visit the UK office, they can’t use their chip-enabled cards even if they want to – ironically, they have to swipe because there’s no PIN, so the reader won’t accept their cards anyway :-)

Pauline

Since the card was heated enough to sustain a little damage, wouldn’t running your finger over the chip reveal something’s not right?

Paul Ducklin

Probably. Unless the crooks are really careful, they’re likely to leave some telltale signs of tampering.

But any physical inspection is a bit like reading through an email to see if it’s a phish – there’s often obvious evidence to condemn it, but an absence of obvious evidence doesn’t mean you can trust it.

We were cautiously confident that by using slightly different tools, plus a trick we figured out to reduce the risk of the card warping, we’d be able to dechip a card cleanly with a lot less heat. (We didn’t have any other old cards to practise on, so we weren’t able to refine our, errrrr, skills…)