Do you travel on the London Underground? The Boston Subway? The Paris Metro? Oxford buses? The San Francisco BART? Sydney Trains? Tokyo’s Yurikamome Line?

Perhaps you’re crushed up against other passengers right now on your morning commute as you read this very article on your mobile phone?

Perhaps you’re waiting for a flight, after rushing through a crowded airport to get to your departure gate in time?

If so, I bet you’ve worried that having a wireless debit card could lead to you being digitally pickpocketed.

Or that having an RFID-enabled passport could lead to your passport details being sniffed out while your documents are safely stashed in your backpack or bumbag.

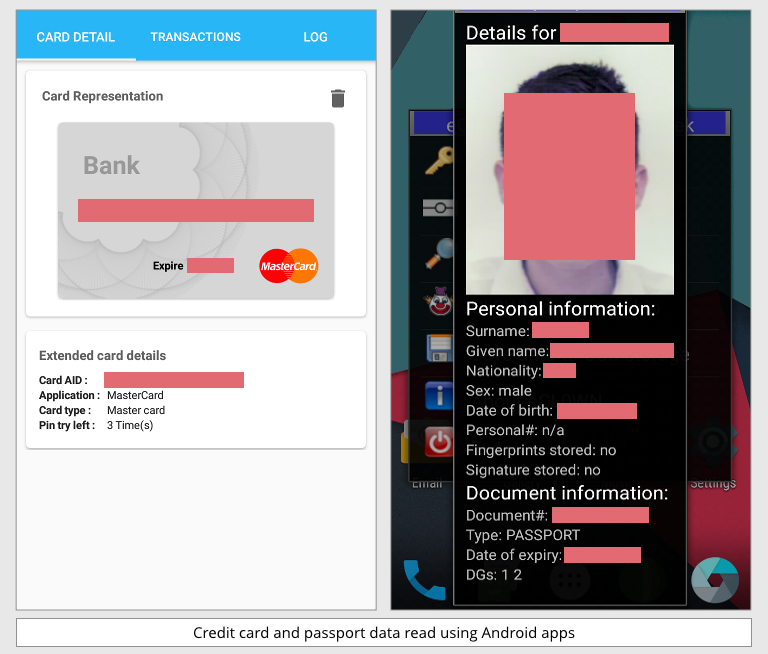

I tried various freely-available Play Store apps on an Android phone, and I could reliably retrieve the following data from a passport and a debit card, all done wirelessly via NFC:

- Debit Card: Long card number, Expiry date.

- Passport: Surname, Given name, Nationality, Gender, Date of birth, Picture, Passport number, Date of expiry.

Be careful if you try this at home. Even if a Play Store app is open source, reviewing the source code to make certain that it doesn’t save or send out your data inapproriately – whether by accident or design – is not easy. I used a test phone that I kept offline while reading the data; I wiped the phone afterwards; and I used expired passports and cards (with the owners’ permision, of course).

Being in the IT security industry, I find I naturally gravitate towards assuming the worst – even if some people call me paranoid or a fan of tinfoil hats.

So, when I got drawn into a recent pub conversation about the necessity of RFID signal-jammers for your wallet – tinfoil hats for your credit cards, in other words – my interest was aroused.

Initially, I scoffed at the idea, having seen a friend try to use an RFID blocking wallet on a wireless building pass, and fail.

But hearing this punter in the local pub insisting that that RFID blocking wallets were not just a good idea but a necessity, I decided to investigate further. Being a stubborn individual with a determination to prove my pub acquaintance wrong, my mission was clear…

…I set about buying various RFID blockers – three different sorts – and started to test.

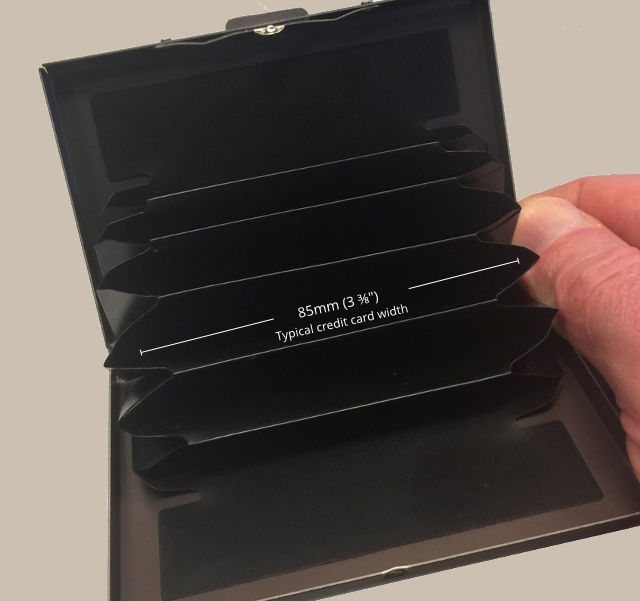

Technology 1: RFID blocking credit card case (brand: Kinzd)

Technology 2: RFID/NFC blocking card (brand: Attenuo)

Technology 3: RFID blocking sleeve (brand: Tenn Well)

The first two of these products are the size of a payment card – only the last one came in a passport-sized sleeve as well – but you’ll be glad to know that the data on your passport isn’t easy to read without you realising it.

Passports use RFID Basic Access Control (BAC) protection to protect passport data. This protection is weaker than using a password (as you do to to log into your laptop or mobile phone, for example), but means that you can’t read digital data from the passport’s chip without first having some data specific to the document.

Only if you provide passport number, expiry date and date of birth up front can you negotiate a BAC session, which then encrypts data travelling between reader and passport.

Loosely speaking, this means that anyone who wants to read the chip on your passport needs to open it at the picture page first, so they can’t just wander through the airport reading off passports that are inside bags, wallets, suitcases and so on.

This protection works because you don’t need to produce your passport very often, and when you do, it’s usually so that an official can scrutinise it physically and digitally at the same time.

Debit and credit cards with contactless payment chips don’t need any sort of authenticated setup before agreeing to pass across information.

The Tube test

How bad could this be?

On a crowded Tube (London Undergound) train, could a malicious individual gather your credit card details through your trousers and wallet whilst holding their phone nearby?

My tests say, “Yes.”

An NFC-enabled mobile phone can accurately scan and record the long card number and expiry date of a debit card that’s stashed in your pocket.

You have to get the phone really close up – but how often do you bump into or brush up against your fellow travellers on busy trains and buses?

So how does this test fare when using the three RFID blocking technologies listed above?

The good news is that in my (admittedly unscientific) experiments, all three blockers prevented my mobile phone from reading the cards, no matter how close I got, and no matter how creepily inappropriately my antics would have been if I were trying to read data from strangers’ pockets on public transport.

Even when I rubbed the card and the phone right up against each other, I couldn’t read anything off the card.

The technicalities

So why is it that my friend’s building pass wasn’t shielded by his RFID blocking wallet?

RFID, short for Radio Frequency Identification, works at a range of different radio frequencies: low, at around 125kHz; high, at 13.56MHz; and ultra-high, at around 900MHz.

NFC, short for Near-field Communication, is a subset of RFID intended for close-up use, and NFC chips use the high-frequency band at 13.56MHz.

RFID readers emit just enough electromagentic energy to induce enough current in the antenna of an RFID or NFC tag (your passport or credit card, for instance) so that the chip can power up, perform calculations and send data.

The antenna thus serves as a medium not only only for transmitting data, but also for transferring power – Nikolai Tesla style.

Many RFID door locks are low-frequency systems running at a higher power, so they’re harder to block with lightweight blocking devices: the low frequency means a longer radio wavelength, which generally means better penetration.

So communication blockers aimed at credit cards and passwords won’t always work to shield building passes, door locks and other low-frequency RFID kit.

What to look for

In case you’re wondering if you do indeed have an RFID enabled passport, check for this symbol. If it’s on your passport then your passport is chip-equipped:

On an NFC-enabled pament card card, you’ll see this symbol:

What to do?

As far as I can tell, rogue NFC transactions initiated by strangers on the train are very rare, so the risk can be considered minuscule – but such attacks are nevertheless technically possible, as a quick test with a mobile phone should convince you.

To my pleasant surprise, all the shielding devices I tried – as well as the homemade approach of using tinfoil, by the way! – seemed to work, at least in my basic, unscientific tests.

However, proving a positive – “can my phone read my credit card through my jeans pocket?” – is easy; proving a negative – “will this RFID wallet always shield my credit card” – is much harder.

So, by all means use an RFID wallet shield – I do, so that guy in the pub won in the end – but don’t stop checking your statements for rogue transactions.

After all, RFID isn’t the only way for your account to get hacked…

Dan D. Lyon

Great article. Real threat, real mitigation.

Matt Boddy

Hey Dan D. Lyon, love the alias. Thanks for your kind words and thanks for reading.

Adrian Venditti

Please can you edit this article to include the price and links to a website page for purchasing the products tested.

Paul Ducklin

We’ll leave it to you to find your favourite place/price for the products we used – I’ve added product identification and the maker’s name for all of them, so any search engine should find you loads of options.

(For the record, we aren’t endorsing any of these, just being clear about the actual products we used when preparing the article, and who makes them.)

Jon

Hi I have found that if two or more credit cards with chips are kept together you cannot just tap your card to pay for items by paywave. Does this mean that they are also protected from being read by others, when the cards are kept together? Are you able to prove this to be correct?

Thanks

Paul Ducklin

If you tap with two cards together, how would the reader know which one you wanted to pay with? Even if you have (say) a train ticket and a payment card, they will interfere with one another and neither is likely to work…but I would not rely on that as a shield for protection.

When paying for an item or tapping a public transport ticket on the bus/train/ferry, explicitly tap the appropriate card only on the reader. Don’t wave a bunch of NFC cards near the reader and expect the reader to guess which one you wanted to use. The system isn’t designed to work that way.

Jim

Yes, that works, but my guess is that it’s nowhere near 100% reliable. It works because, as Paul says, the reader can’t tell the cards apart.

However, I suspect that that limitation could be overcome by software that takes all the data, and splits it up. I don’t know that such software exists, but I wouldn’t rely on it’s non-existence to give me any sort of warm, fuzzy feeling.

Paul Ducklin

In all the informal testing I have done (not for this particular article) with two cards held together, the results were:

* No read of either card. (Perhaps 95% of the time.)

* Read of the card at the back, furthest from the reader. (Perhaps 5% of the time.)

No science or formality in those experiments. I was just being curious.

Eric

Good article; I like how you pointed out the difference between systems and what they’ll go through. A lot of people think that one-size-fits-all when it comes to making anything “safe,” which it isn’t.

By the way, I saw a minor glitch in the article – “On on RFID-enabled pament card card”

Paul Ducklin

Fixed that typo, thanks!

Matt Boddy

Thank you Eric!

Mahhn

I’ve received CC protectors at conferences and after seeing a demo similar to your test at Defcon 2 years ago, my CC is in one unless being used.

However, (just to save others time trying) I took a hip bag and put a 10 layers of aluminum foil pocket in it to test blocking wifi and cell signal – like your door badge test, it was a total fail, phone rang and IM’s worked. I was going to try copper (which should work) but haven’t bothered yet.

Mark

interesting read for a Friday afternoon at work :)

Matt Boddy

Thanks Mark!

MikeP

I liked that article but many more people need to be aware of the risks and how simple it is to mitigate or prevent such events.

As an electronics engineer, I once worked for Network Rail and often visited various parts of London using the tube. A colleague had an Oyster card and walked through Paddington Station. He passed near the card reader used at the entry to the tube but then headed to his overground platform. When he got his next Oyster statement he had been billed for a tube journey even though he didn’t pass through the gate, only near it. Ever sincethen, I’ve used a shield based on Faraday Cage principles and needing no power, they’re cheap to buy and easy to use. It works with credit/debit card. Not tried it with my passport yet, I rarely used it anyway.

Lillie-Beth (@lillie_beth)

I don’t see the wireless symbol on my debit card, nor do I see that other symbol on my 2011 passport (I’ll check my daughter’s newer one when I get home). How prevalent are these types of cards now? I was worried that any card with a chip could be read like this but after looking for the symbol, I’m not sure. Also, can they lift the number from your Apple Pay? Thanks for the information!

Paul Ducklin

My UK passport is RFID-chipped and has the logo shown above. But I just looked at a recently-issued non-EU passport that is chipped and does not have the logo. So perhaps the logo is an EU thing? There may be countries that still issue unchipped passports, but I can’t imagine they’d be accepted in any country that has mandated chipped passports.

On the other hand, my most recent payment card does not have NFC (and does not have the logo), but IIRC that was a choice – I seem to think that my bank issues non-NFC cards by default and you have to tick a box to receive one capable of contactless payments.

John

Very nice article. Like you, I always wondered about those solutions. Now I know!

Matt Boddy

Thank you John!

Scott Johnson

I did a bit of reading on this. Sure the information can be read but after a certain amount of money debit a pin needs to be entered (for me that’s $100). Each transaction has it’s own code and all remote reading of a card gives a thief is the card number and the last code used. Use that code a second time and the system flags it as a fraudulent transaction.

Paul Ducklin

Well, in the article we do use the word “minuscule” to describe the risk…

…but you do get the long number and the expiry date just by waving a suitably-configured phone near an NFC credit card.

I wouldn’t be comfortable with someone taking a photo of the front of my card (that would not record the CVV code), and I expect printed receipts not to show all the digits of my long number. So putting your card in a shielding wallet might not be necessary, but there seems to be little harm in it, and the wallets we tried seemed to do what they said. In short: don’t laugh at people who do it. They are neither silly nor paranoid.

Also, as an earlier commenter pointed out, there are other cards, such as public transport tickets, that may be worth putting into a shielding wallet just to stop you accidentally billing yourself for journeys you didn’t make…

roleary

Is it a suffient test of an rfid-blocker to see if it stops you paying at a self-service checkout?

I bought a cheap one from a fuel station and apart from one of the hinges busting (duct tape to the rescue!) it seems to be working fine.

Cynthia abdallah

Great article Matt. 👍

Robin Tanswell

I just laminated a piece of aluminium foil, cut to a size of a credit card and placed it between my credit card and wallet. Tested it successfully against my NFC phone.

Paul Ducklin

As mentioned above, we had success with foil, too, at least when we put the card on a piece of foil. But we found that if the foil and the wallet got separated even slightly – by just a millimetre or two – then the shielding effect was lost.

Neil

Really interesting stuff and well-written. Nice work Matt!

Matt Boddy

Thanks Neil :)

Norman Crocker

Hi, a good article, clear and enough technical detail supplied to actually be useful.. I have been using sheilding CC wallets for about 5 years for all my enabled cards. Not only do they work they also provide physical protection for the card against ‘rubbing’ damage in normal use. A pack of 10 can be bought very cheaply on Amazon. I would say they are vital – the banks should ship each card in one free when issued since the card could be scanned in the post before the owner ever gets it. I personally would avoid wrapping a card in conducting foil to avoid electrostatic damage to the chip. Note also that allthough the technology is called ‘Near Field’ it actualy works over longer distances (2 or 3 meters) using adapted readers with higher radio power provided there is only one card in range.