What can a powerful, all-seeing algorithm predict about you, based on your online footprint, publicly available information and Facebook Likes?

I, whom you can henceforth refer to as Human #1067494, have found out.

To do so, I’ve engaged with an online environment called Predictive World: an interface to process users’ data that was recently released by videogame publisher Ubisoft.

To partake, you either have to agree to let the program access your Facebook profile (for the most accurate profiling) or to hand over basic information on your own.

The game-maker developed Predictive World in collaboration with the Psychometrics Centre of the University of Cambridge.

Based on their research, the thinking goes, it can generate accurate predictions of who we are, how many pints we put away every week, how much we weigh, how tall we are, how much we smoke, and when we’re going to die, among many other variables.

The game-maker has delved into the dangers of big data and predictive algorithms as one of the themes of its action-adventure game Watch Dogs 2: a game in which hero Marcus Holloway is wrongly profiled as a main suspect for a crime he didn’t commit by a city-wide operating system that collects and analyzes data on all citizens.

Ubisoft assures us that this is where fiction meets reality. Predictive World is all about demonstrating how seemingly trivial data about us can be pulled together and processed into profiles and patterns:

Each day, we leave a trail of more than 5 billion gigabytes of data behind us. This information comes from billions of collection points: from online transactions of course, to GPS signals, social media likes, texts we exchange, or even parking tickets, soda dispensers, etc.

They are then sold, bought, and analysed through different touch points in order to create strong and accurate probabilities on who we are or what we’re most likely to do.

As we often write about on Naked Security, Big Data covers many categories.

It’s not necessarily the photos you snap of your cat, for example.

But the term most certainly includes a collection of a million different cats, organized by location as precise as street address, that you may have contributed to by making your photo APIs publicly available on sites like Flickr, Twitpic, Instagram or the like.

You can take that scenario and replicate it on all the sites where our data is amassed: Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras are another good example of how we can be tracked, given that our plate numbers stay the same while our locations change.

In fact, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has been building a national license plate reader (LPR) database over several years that it shares with federal and local authorities, with no clarity on whether the network is subject to court oversight.

Then too, there’s the giant database of Wi-Fi access points from Google’s StreetView cars that it was using to aid and abet its geolocation services.

Predictive World is far from the first online tool to crunch our online selves to show us how all those Big Data players come up with profiles. Those profiles can be used, for example, to pass us over for jobs, given that most recruiters nowadays pore over our social network profiles before they decide whether to call us in for an interview.

One example of the tools used to demonstrate the data trails we leave behind was a site called “We know what you’re doing”. It aggregated some of our choicer social media content for us, delivered courtesy of Facebook via its Graph API.

Another was Please Rob Me. When it launched in 2010, it was using check-in data from the location-based Foursquare social network that was subsequently posted to Twitter.

When the information becomes publicly available on Twitter, it makes it theoretically possible for a robber to know when you’re away from home.

Well, maybe it was theoretical when they launched the site, but it sure didn’t stay theoretical for long. One set of burglars put the theory to the test by breaking into the home of friends after reading their Facebook updates to find out when they’d be away.

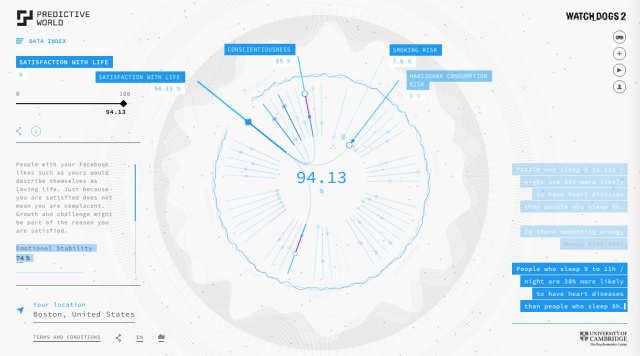

But back to Predictive World. After you sign in (I allowed it access to my Facebook profile to see how well it would do when spoon-fed), it collects data such as your gender, age, and pages you’ve liked, and combines them with local demographics to generate a profile of who you are.

How did it do?

Wow, the details that can be gleaned about you from Facebook!

Wow, how wrong they can be!

Predictive World believes that I’m tall, fat, have a 12.8% chance of smoking pot, make about double the minimum wage, have a conscientiousness factor of something like 43%, and will die at the age of 84.9 years.

Wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong.

So let’s reframe the initial question: what can a powerful algorithm that corporations or police may well consider to be all-seeing but is in actuality peering through cracked glasses with severe myopia guess about you based on your online footprint?

In my case, it guessed that I’m 4″ taller than I am, that I weigh 49 lbs. more than I do, that I make 31% of what I actually earn, that I drink two pints of beer a week (are you kidding?! I’m gluten intolerant!), and that my “risk” of smoking marijuana is 12.8%

How much do those, and myriad other inaccuracies, affect predictive analytics?

A lot, if Predictive World is indicative: my life expectancy shot up from 84.9 years to 95.1 when I corrected those variables.

While it’s easy to see where big data can siphon concrete personal information such as our age or our location from Facebook (if we’ve made such data public and haven’t lied about it), it’s worth asking how it guesses at more subjective things, such as our level of satisfaction with life.

Predictive World is happy to tell you. You can click on each one of a series of rays that emanates from a throbbing circular graphic to get details on how a particular variable is derived.

For instance, people who like the same things as I do on Facebook tend to describe themselves as loving life. It can’t be all about the likes, though: my 94.13% satisfaction level shot up from 63% after I told the tool I wasn’t as poor as it initially assumed.

It isn’t, in fact, all about the likes. Predictive World is based on an algorithm developed by the Psychometrics Centre using a wide range of data sources, such as psychological and social media data from more than 6 million research participants, along with a bespoke infrastructure designed for the project that contains 6.3 billion data points.

That enables Predictive World to visualize the relationships between gender and salary, location and crime risk, personality and longevity, and much more.

Collecting and processing users’ digital footprints and combining predictions with open data, the system is able to make 70 data-driven predictions about an individual, from personality traits and intelligence to life expectancy and even financial risk propensity.

But does it really matter if it’s accurate or not?

What’s worth noting is that this kind of information can be, and is being, used to build up detailed profiles of us. Not necessarily accurate, mind you, but highly detailed nonetheless.

Earlier in the month, for example, before Facebook called off the plan, a UK car insurer was going to use young drivers’ data to analyze their personalities and offer quotes based on their profiles.

Predictive World posed this question: do I want my insurance company to have this type of information about me?

No, I can’t say that I do.

I don’t know which would be worse: having insurance companies think I’m going to die at 85 so they can offer me long-term care and not go broke; have them find out I’m diabetic (Predictive World doesn’t seem to know that; if it did, it would probably have guessed, based on average life expectancy of diabetics, that I had already kicked the bucket); or having insurers construct a more accurate profile of me so they can drop me like a hot potato when they find out that diabetes thing.

I don’t know whether I want to sharpen the accuracy of Predictive World’s, or insurance companies’ or banks’, vision of who I am. I’m leaning toward keeping my Facebook profile nice and fuzzy.

What’s your plan?

Anonymous

Once there’s a system that matters, it will be easy to game.

Anonymous

My FB profile doesn’t even use my real name.

Brian T. Nakamoto

I guess it’s somewhat comforting that this promo for a video game is totally wrong about me too.