Big news!

The Grand Final of cryptographic lawsuits is over, abandoned shortly before the last quarter of play.

You know what we’re referring to, of course: the FBI versus Apple court case that saw the US judiciary tell Apple, “You must provide the FBI with a backdoor to circumvent iPhone security in order to assist a criminal investigation.”

Regulators and law enforcement in many jurisdictions have been pressing for mandatory computer security backdoors for years, claiming that modern-day encryption software is so strong that crooks, terrorists and foreign spies can hide behind it and thereby evade both detection and prosecution.

Therefore, say anti-encryption campaigners, we need to have backdoors programmed into security products by law, so that duly-authorised officials can sidestep security when necessary.

FBI versus Apple

Greatly simplified, that was the case that the FBI made against Apple in its recent lawsuit, and the court agreed.

Rather than going to court for a blanket right to unlock iPhones in the future, the FBI chose a specific iPhone connected with a particularly abhorrent crime: the 2015 mass shootings in San Bernadino, California.

Two shooters were involved, a man and his wife who murdered 14 people before fleeing from the police a rented vehicle, only to end up dead themselves after trying to shoot it out with the police from inside their car.

The couple had apparently destroyed their own mobile phones before undertaking the attack, but the husbands’s work phone, technically the property of the San Bernadino council, was bagged by the FBI to see what investigative intelligence it could reveal, if any.

That’s what led to the court case, when the FBI found itself stuck up against the iPhone’s passcode.

If you’ve configured your own iPhone for security, you’ve probably set a passcode of your own, so that your device can’t easily be used for evil if someone steals it and sells it on for further criminal activity by crooks, terrorists or foreign spies.

After all, strong encryption is nowadays much more about protecting us from the Bad Guys than the other way around. (You only need to look at the number and the magnitude of recent data breaches to see why we need data protection more then ever.)

A cop who seizes a passcode-protected iPhone could try guessing the most likely passcodes, but it’s a slow process that is designed so that it can only be carried out on the iPhone itself.

In theory, at least, you can’t just copy the iPhone’s memory and storage and attack the passcode offline at any speed you like.

Robots to the rescue

Robotic passcode testing devices exist that can type in passcodes much faster, more accurately, and for far longer than a human can manage…

…but iPhones have a secondary security setting that makes the device wipe all its data after 10 incorrect guesses.

That’s the same sort of protection used by financial institutions at ATMs, whereby the cashpoint machine swallows your bank card after three mistakes, so that a crook who steals your card has only a tiny chance of getting it to work.

Apparently, the FBI had already changed the murderer’s Apple ID password in order to access data he may have stored in Apple’s iCloud, instead of first trying to induce the locked-but-alive iPhone to sync its local data first, and only then going after the data in the cloud.

Thus the lawsuit, intended to force Apple to assist against its own judgment by deliberately “backdooring” its way around existing security measures, using a technique that critics said was far too general, and would create a dangerous precedent for all security vendors in the future.

It’s one thing to work with existing security vulnerabilities to recover protected data, but quite another, says the #nobackdoors argument, to create and deploy a purposeful security vulnerability that didn’t exist before.

Simply put, you can’t make security stronger for the future by deliberately weakening it.

After all, if you do deliberately weaken it, you create a hole that potentially puts everyone at risk, notably the law-abiding amongst us.

(Crooks don’t really care about backdoors. They’re crooks, so they’re unlikely to comply with any laws that require the use of backdoored encryption. They’ll just use unencumbered encryption software instead of or as well as the deliberately-weakened tools foisted on the rest of us.)

💡 LISTEN NOW: Live podcast – The Great “Backdoor” debate” ►

Peace with honour?

So, why has the FBI abandoned its lawsuit, at least for now?

According to media outlets the world over, a spokesperson for the US Department of Justice gave this reason:

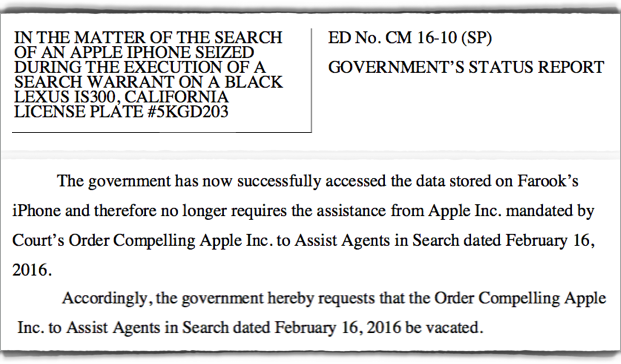

As the government noted in its filing today [Monday 2016-03-28], the FBI has now successfully retrieved the data stored on the San Bernardino terrorist’s iPhone and therefore no longer requires the assistance from Apple required by this Court Order. The FBI is currently reviewing the information on the phone, consistent with standard investigatory procedures.

And here’s how the government put it to the court:

What next?

What we don’t know, and the FBI isn’t saying, is exactly what was retrieved, or how.

- Perhaps the passcode was 0000 or 2580, and the FBI got lucky?

- Perhaps the lock-out limit on guessing wasn’t turned on and so the FBI had thousands of tries, not just 10?

- Perhaps the iPhone had enough unencrypted data left in RAM (rather than encrypted in flash storage) to help the investigation, or to leak the passcode?

- Perhaps the FBI had a way of re-writing the iPhone’s RAM and flash storage to allow 10 guesses over and over again, albeit slowly?

- Perhaps the FBI purchased an existing zero-day vulnerability in iOS to allow it to bypass security through an unintentional backdoor?

- Perhaps the FBI recovered the passcode via some smart image processing, using fingerprint grease stains on the screen to infer the digits that had been used?

What we can assume is this:

- This courtcase is over, but the principle of legally-mandated backdoors is no closer to being settled.

- Apple will be trying to figure out what the FBI did, and how to patch it.

After all, if Apple can figure out how the Feds got in, then so can anyway else, especially if information about how it was done leaks out. (Security through obscurity is a poor basis for cryptographic protection.)

As a result, the rest of us will want the hole fixed once it’s known…

…and so, we have to assume, will any number of regulatory bodies around the world, such as Information Commissioners’ Offices.

Ironically, privacy and data security regulators are widely tasked with using legal pressure to reduce the number of security holes that could lead to data breaches, privacy violations, and identity theft.

Terry

I don’t think they did get in. This just gives them an out. If the former head of CIA and NSA is siding with Apple they would have an unlikely chance of winning this case.

Paul Ducklin

“Successfully accessed the data” doesn’t quite say how far they got and it definitely leaves “how” a handy mystery :-) And it doesn’t actually mention whether the device ended up unlocked and accessed generically, or merely accessed to some extent.

Brendan Taylor

Multiple reports that is was Cellebrite helped them achieve this. Any information on that? Or all just speculation/rumor?

Paul Ducklin

You have to decide that for yourself :-)

Maybe they got help from more than one source? After all, both Dutch and Canadian police claim to have had success against strongly-encrypted mobile devices recently:

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2016/01/13/police-say-they-can-crack-blackberry-pgp-encrypted-email/

JR

Didn’t John McAfee offer to crack the data also? That info gem seemed to disappear fairly quickly.

Paul Ducklin

He did. IIRC he claimed it would take “half an hour” – you simply decompile the firmware, he said, until you find the instructions where the passcode is being accessed and then just read it out of the relevant memory location. The really sad thing is that I think Mr McAfee actually believed himself. (Apple’s own documentation explains rather well how the bootup process works and how the passcode is used. It’s not stored anywhere; it’s just part of the process used to decrypt the AES key, which is stored in a tamper-proof module called the secure enclave, part of the fingerprint sensor hardware. Too many wrong passcodes – if that option is turned on – and the secure enclave gets wiped. And you can’t “just read out the contents of the secure enclave”, because it’s specifically designed so that you although you can choose what to write into it, you can only get out the results of specific cryptographic computations on what’s inside it. A bit like the chips on credit cards and the like.)

Bryan

I still wouldn’t mind watching him chew on a pair of hush-puppies

Anonymous

“The Superbowl of cryptographic lawsuits is over, abandoned shortly before the final PERIOD of play.”

Geeks should know better than to use sports for similes.

LOL

Superbowl’s have quarters. Hockey games have “periods”

Paul Ducklin

I meant to write period (and thus I did) specifically to avoid the word quarter, which is an unusual subdivision outside of the American and Australian football codes and might therefore appear slightly quirky to many readers.

I consider the word period to be unexceptionable in the sense of “each of the divisions into which a sporting event is organised,” and my American English Dictionary agrees, not least because that is the definition it gives.

In other words, you can, without confusion, take “the final period” to refer to the final third of ice hockey game; the second half of a regular hockey game in countries where you are allowed to play without freezing the ground first; the last quarter of an Australian football match; or perhaps the time between tea and stumps on the last day of a five-day cricket test match (a period more properly called a session).

By the way, in your comment, there shouldn’t be an apostrophe in the word Superbowls, and I would avoid the plural of that word anyway, reminding us that each Grand Final stands alone.

Also, you ought to leave the air-quotes off the last word. (Hockey doesn’t have “periods”, which suggests that the word fits only vaguely. It has periods, officially and in common parlance.)

And it’s a metaphor, not a simile.

A simile is where you make an explicit comparison, not where you use one concept to represent another. “The FBI lawsuit against Apple fizzled out like a cricket match that was stopped by bad light just when it started to get exciting” would be a sporting simile, albeit not a terribly good one.

Oh, and since you introduced the word: geek risks being insulting. I suggest avoiding it in print.

(You started it :-)

JR

If you want to be accurate, nowhere would the term “period” be used in American football. That would be like calling it an inning. Also, there is no such thing as a “Superbowl”, as it is known as the “Super Bowl”… but then you probably knew that, thus avoiding a trademark infringement, and also avoiding the inevitable, yet ridiculous, “Big Game” term.

Paul Ducklin

I’m giving in. I am changing the article to be unashamedly Oztraylian. It will now say, “the last quarter of the Grand Final.” Put *that* in your bowl and smoke it :-)

ichabod

printed quotation marks are not air quotes.

Paul Ducklin

They’re still an orthographic error because they serve as air-quotes.

Michael Snow

“The Superbowl of cryptographic lawsuits is over, abandoned shortly before the final PERIOD of play.”

Geeks should know better than to use sports for similes.

LOL

Superbowl’s have quarters. Hockey games have “periods”

barfolemeow

“mass shooting”??? I thought this was an act of terrorism. With your choice of words and apparent mindset we can sum up World War II as “an exchange of aggressive fire between adversaries”.. Just saying.

Paul Ducklin

If you shoot 14 people dead in cold blood, you are a mass murderer. I don’t know how much more plainly you can say it, or why that might be a problem. Of some importance in this case is that there was no chance of either perpetrator assisting police (or even of refusing to assist them) because of the gun battle during their attempted escape.

barfolemeow

Paul, I completely agree. I am just always concerned when I see the word “terrorist” replaced with anything else. To me it screams political correctness. Anyway I apologize for taking this article off-topic.

Don McAdams

Mass shootings are a form of terrorism, by definition. /js

Steve

Quite true. They are not synonyms, but either can be a subset of the other.

4caster

Thank goodness it was the FBI who managed to crack the iPhone. That is their job, and I hope they succeed in catching the criminals. They can’t be expected to tell Apple or anyone else how they did it. At the same time, it will be Apple’s job to close the security gap before less scrupulous people can use it.

Jim

In the security biz, it is frequently said that “if you have physical access, all bets are off”. The hardware would have to be keyed to the encryption in order to stop decryption attempts once the device is in the hands of the cracker.

That COULD be done, but it would mean that the hardware is different in every device. Such a practice would be prohibitively expensive. No company could possibly sell it to the masses.

Paul Ducklin

It is frequently said, but it is not really true. Not in the 21st century. Good luck reading key data out of Apple’s secure enclave (tamper-resistant storage) in newer iPhones, for example. Good luck reading the crypto keys out of your mobile phone SIM. Good luck cloning your SIM card. (Crooks don’t do that any more. They go to a crooked or sloppy phone shop and order a new SIM programmed with someone else’s number – the dreaded “SIM swap” attack, like what you’d do if you bought a new phone that needed a different SIM format. They exploit the issuing procedure rather than tampering with the chip.)

And, yes, Apple devices are cryptographically unique, so that the hardware *is* different in each device. After all, when you buy an iPhone, it comes with iOS on it, so it’s automatically customised during manufacture. That initialisation includes burning a unique ID into the hardware. This is a must-read:

https://www.apple.com/business/docs/iOS_Security_Guide.pdf

Jack

you guys are getting *way* too tabloid, reading your content ~10% of the time I used to… just sayin’

Paul Ducklin

Are you suggesting this article is Tabloidistic? If so I am insulted.

Jack

I guess you didn’t see the reports from a number of locals in San Bernardino that they saw 3 large white men in black .mil gear carrying large rifles doing the shooting. Additionally, the woman of the couple was too small to carry and operate the kind of weapons used, and she and her husband had been at a work party with *their young children* earlier that same week having a party with the people they would later come back and shoot. Something isn’t right with this story.

Paul Ducklin

That’s interesting but it’s not directly relevant to accessing a locked iPhone that has a connection of some sort to the case, which is the issue here.

Don McAdams

There is another possible answer as to “how” they cracked it – What if Apple secretly helped the FBI get into the phone to make this go away…? Somebody else mentioned former heads of CIA and NSA being on Apple’s side. I haven’t verified that, but with Apple’s financial might, alone, I can see them saying, “here’s your access, now drop this backdoor nonsense immediately.” As you said, it would mandate a vulnerability that no security experts, manufacturers, or consumers want. If Apple has a known vulnerability, this conspiracy theory would help them keep it under wraps. This could also be related to the zero-day explanation, but that theory felt more external than internal.

Bryan

“What if Apple secretly helped the FBI get into the phone to make this go away”

Possible, but unlikely. Edward Snowden was once trusted by his employer, and (whether we agree or not) he felt truth outweighed his prior oath. Same with Apple secreting a fix to the feds, same with Dubya masterminding 9/11. Sooner or later all it takes is one drunken braggart dying to impress someone (either with their accomplishments or perceived import), one guilty conscience, one guy too trusting with his girlfriend, et cetera; the story blows wide open.

Apple has far too much to lose by risking exposure of a clandestine acquiescence. My money’s against it–as opposed to a yet-unknown zero-day exploit or some physical deconstruction wizardry.

Will

You’re absolutely right that there isn’t definitive evidence showing how they got in, but it seems more than just coincidence that someone comes forward to the FBI demonstrating an exploit, a notice then subsequently going out to delay the hearing, and finally this dismissal. That leads me to believe there is some zero-day in the wild that was used.

In either case, this wasn’t the outcome I had been hoping for, because as you noted, it just delays the inevitable discussion to a later date.

Ayvalen

“Perhaps the lock-out limit on guessing wasn’t turned on and so the FBI had thousands of tries, not just 10?”

This doesn’t work. Whether the wipe after 10 tries setting is turned on or not, the moment you try the passcode incorrectly 10 times the iPhone is permanently disabled and the passcode no longer works. It starts off locking you out for 1, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes and eventually forever when you put in the passcode incorrect more than 5 times.

Paul Ducklin

Hmmm, yes, you are right. There’s something on that here:

https://support.apple.com/en-gb/HT204306

(Apple says “six time in a row”, not five. Also, I’d avoid saying “permanently disabled,” which sounds like “bricked” to me. You can reflash iOS, but that’s like buying a new phone with no apps and no data. (I do that every few iOS updates, needed or not. Life’s too short to keep photos that you haven’t looked at for six months or more. If they aren’t worth backing up, then they aren’t worth keeping at all. It’s like that old bicycle you haven’t ridden for 15 years. Give it to someone who wants to restore it.)

Bad Al

Pretty simple, If they cracked the security and then announced it they obviously found nothing of value to them. On the other hand if they cracked it and found damming evidence of accomplices they would say nothing till all leads were followed up.