Samba, simply put, is a super-useful, mega-popular, open-source reimplementation of the networking protocols used in Microsoft Windows, and its historical importance in internetworking (connecting two different sorts of network together) cannot be underestimated.

In the late 1990s, Microsoft networking shed its opaque, proprietary nature and became an open standard known as CIFS, short for common internet file system.

But there was nothing “common” or “open” about it in the early 1990s, when Australian academic Andrew Tridgell set out to correct that by implementing a compatible system that would let him connect his Unix computer to a Windows network, and vice versa.

Back then, the protocol was officially referred to as SMB, short for server message block (a name that you still hear much more frequently than CIFS), so Tridge, as Andrew Tridgell is known, understandably referred to his project “SMBserver”, because that’s what it was.

But it turned out that commercial product of that name already existed, so a new moniker was needed.

That’s when the project became known as Samba, a delightfully memorable name that resulted from a dictionary search for words of the form S?M?B?.

In fact, samba is still the first word out of the gate alphabetically in the dict file commonly found on Unix computers, followed by the rather ill-fitting word scramble and the totally inappropriate scumbag:

Some bugs you make, but some bugs you get

Over the years the Samba project has not only introduced and fixed its own unique bugs, as any complex software project generally does, but also inherited bugs and shortcomings in the underlying protocol, given that its goal has always been to work seamlessly with Windows networks.

(Sadly, so-called bug compatibility is often an unavoidable part of building a new system that works alongside an old one.)

Late in 2022, one of those “inherited vulnerabilities” was found and reported to Microsoft, given the identifier CVE-2022-38023, and patched in the November 2022 Patch Tuesday update.

This bug could have allowed an attacker to change the content of some network data packets without getting detected, despite the use of cryptographic MACs (message authentication codes) intended to prevent spoofing and tampering.

Notably, by manipulating data at logon time, cunning cybercriminals could pull off an elevation-of-privilege (EoP) attack.

They could, in theory at least, trick a server into thinking they’d passed the “do you have Administrator credentials?” test, even though they didn’t have those credentials and their fake data should have failed its cryptographic verification.

Cryptographic agility

We decided to write about this rather esoteric bug not because we think you’re likely to be exploited by it (though when it comes to cybersecurity, we take the attitude never say never), but because it’s a yet another reminder of why cryptographic agility is important.

Collectively, we need both the skill and the will to leave beind old algorithms for good as soon as they’re found to be flawed, and not to leave them lying around indefinitely until they turn into somebody else’s problem. (That “somebody else” may well turn out to be us, ten years down the road.)

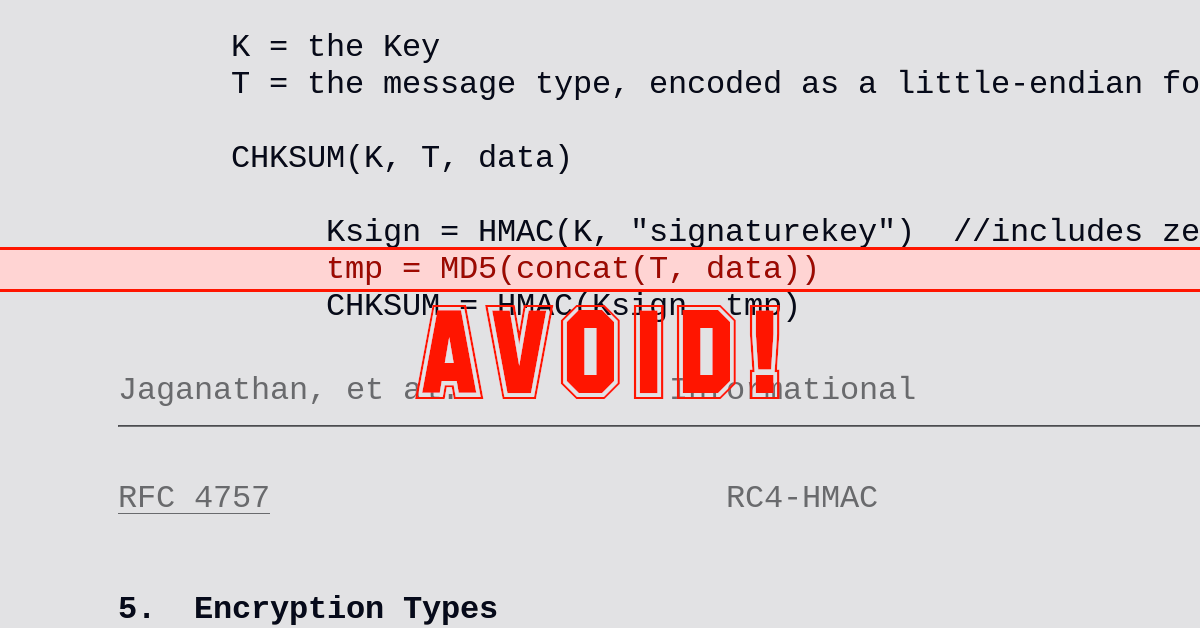

Astonishingly, the CVE-2022-38023 vulnerability existed in the first place because both Windows and Samba still supported a style of integrity protection based on the long-deprecated hashing algorithm MD5.

Simply put, network authentication using Microsoft’s version of the Kerberos protocol still allowed data to be integrity-protected (or checksummed, to use the casual but not strictly accurate jargon term) using flawed cryptography.

You shouldn’t be using MD5 any more because it’s considered broken: a determined attacker can easily come up with two different inputs that end up with the same MD5 hash.

As you probably already know, however, one of the requirements of any cryptographic-quality hash is that this simply shouldn’t be possible.

In the jargon, two inputs with the same hash cause what is known as a collision, and there aren’t supposed to be any programmatic tricks or shortcuts to help you find one quickly.

There should be no way to find a collision that’s faster than relying entirely on luck – trying over and over again with ever-changing input files until you hit the jackpot.

The true cost of a collision

Assuming a reliable algorithm, with no exploitable weaknesses, you’d expect that a hash with X bits of output would need about 2X-1 tries to find a second input that collided with the hash of an existing file.

Even if all you wanted to do was to find any two inputs (two arbitrary inputs, regardless of content, size or structure) that just happened to have the same hash, you’d expect to need slightly more than 2X/2 tries before you hit upon a collision.

Any hashing algorithm that can be reliably “cracked” faster than that isn’t cryptographically safe, because you’ve shown that its internal process for mixing up the data that’s fed into it doesn’t produce a truly pseudorandom result, which it ought to.

Note that any better-than-chance cracking procedure, even if it only speeds up the collision generation process slightly and therefore wouldn’t currently be an exploitable risk in real life, destroys faith in the underlying cryptographic algorithm by undermining its claims of cryptographic correctness.

If there are 2X different possible hash outputs, you’d hope to hit a 50:50 chance of finding an input with a specific, pre-determined hash after about half as many tries, and 2X/2 = 2X-1. Finding any two files that collide is easier, because every time you try a new input, you win if your new hash collides with any of the previous inputs you’ve already tried, because any pair of inputs is allowed. For a collision of the “any two files in this giant bucket will do” sort, you hit the 50:50 chance of success at just slightly more than the square root of the number of possible hashes, and √2X = 2X/2. So, for a 128-bit hash such as MD5, you’d expect, on average, to hash about 2127 blocks to match a specific output value, and 264 blocks to find any pair of colliding inputs.

Fast MD5 collisions made easy

As it happens, you can’t easily generate two completely different, unrelated, pseudorandom inputs that have the the same MD5 hash.

And you can’t easily go backwards from an MD5 hash to uncover anything about the specific input that produced it, which is another cryptographic promise that a reliable hash needs to keep.

But if you start with two identical inputs and carefully insert a deliberately-calculated pair of “collision-building” chunks at the same point in each input stream, you can reliably create MD5 collisions in seconds, even on a modest laptop.

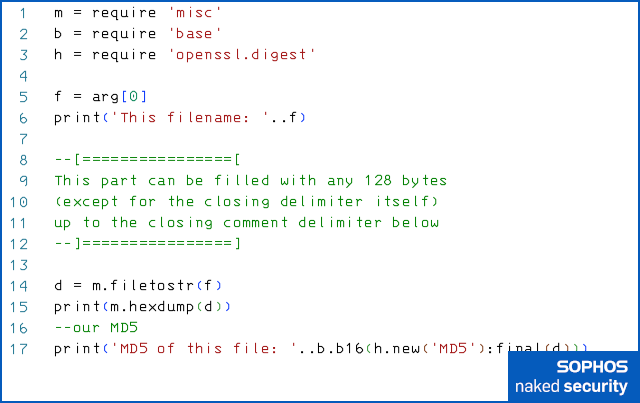

For example, here’s a Lua program we wrote that can conveniently be chopped into three distinct sections, each 128 bytes long.

There’s a code prefix that ends with a line of text that starts a Lua comment (the string starting --[== in line 8), then there are 128 bytes of comment text that can be replaced with anything we like, because it’s ignored when the file runs (lines 9 to 11), and there’s a code suffix of 128 bytes that closes the comment (the string starting --]== in line 12) and finishes off the program.

Even if you’re not a programmer, you can probably see that the active code reads in the contents [line 14] of the source code file itself (in Lua, the value arg[0] on line 5 is the name of the script file that you’re currently running), then prints it out as a hex dump [line 15] , followed by its MD5 hash [line 17]:

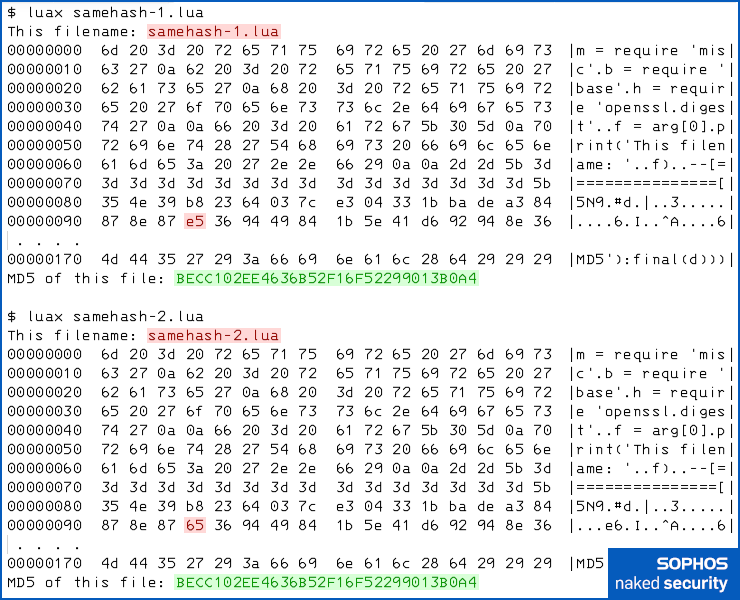

Running the file is essentially self-descriptive, and makes the three 128-byte blocks obvious:

Using an MD5 research tool called md5_fastcoll, originally created by mathematician Marc Stevens as part of his Masters’ degree in cryptography back in 2007, we quickly produced two 128-byte “MD5 collision-building” chunks that we used to replace the comment text shown in the file above.

This created two files that both still work as they did before, because the changes are confined to the comment, which doesn’t affect the executable code in either file.

But they are visibly different in several bytes, and should therefore have completely different hash values, as the following code diff (jargon for dump of detected differences) reveals.

We’ve converted the 128-byte collision-creating chunks, which don’t make sense as printable text, into hexadecimal for clarity:

Running them both, however, clearly shows that they represent a hash collision, because they have the same MD5 output:

Collision complexity explored

MD5 is a 128-bit hash, as the output strings above make clear.

So, as mentioned before, we’d expect to need about 2128/2, or 264 tries on average in order to produce an MD5 collision of any sort.

That means processing a mimimum of about 18 quintillion MD5 hash blocks, because 264 = 18,446,744,073,709,551,616.

At an estimated peak MD5 hash rate of about 50,000,000 blocks/second on our laptop, that means we’d have to wait more than 10,000 years, and although well-funded attackers might easily go 10,000 to 100,000 times faster than that, even they would be waiting weeks or months just for a single random (and not necessarily useful) collison to turn up.

Yet the above pair of two-faced Lua files, which have exactly the same MD5 hash despite quite clearly not being identical, took us a just a few seconds to prepare.

Indeed, generating 10 different collisions for 10 files, using 10 different starting prefixes that we chose ourselves, took us: 14.9sec, 4.7sec, 2.6sec, 2.1sec, 10.5sec, 2.4sec, 2.0sec, 0.14sec, 8.4sec, and 0.43sec.

Clearly, MD5’s cryptographic promise to provide what’s known as collision resistance is fundamentally broken…

…apparently by a factor of at least 25 billion, based on dividing the average time we’d expect to wait to find a collision (thousands of years, as estimated above) by the worst time we actually measured (14.9 seconds) while churning out ten different collisions just for this article.

The authentication flaw explained

But what about the unsafe use of MD5 in CVE-2022-38023?

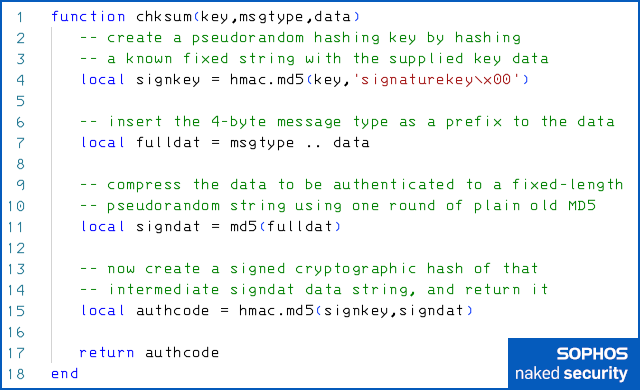

In Lua-style pseudocode, the defective message authentication code used during logons was calculated like this:

To explain: the authentication code that’s used is calculated by the hmac.md5() function call in line 15, using what’s known as a keyed hash, in this case HMAC-MD5.

The name HMAC is short for cryptographic construction for generating hash-based message authentication codes, and the -MD5 suffix denotes the hashing algorithm it’s using internally.

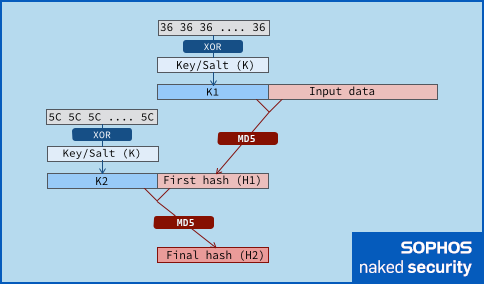

HMAC uses a secret key, combined with two invocations of the underlying hash, instead of just one, to produce its message authentication code:

The key has some of its bits flipped first, and gets prepended to the supplied data before the first hash starts.

This greatly reduces the control that cryptographic crackers have, when they are trying to provoke a collision or other non-random behaviour in the hashing process, over the internal state of the hash function when the first bytes of the input data are reached.

Notably, the secret key prevents attackers from starting with a message prefix of their own choice, as we did in the twohash.lua example above.

Then, once the first hash is calculated, the key has a different set of bits flipped, gets prepended to that first hash value, and this new input data is hashed a second time.

This prevents the attackers from manipulating the final part of the HMAC calculation, too, notably preventing them appending a suffix of their own choice to the last stage of the hashing process.

Indeed, even though you shouldn’t be using MD5 at all, we’re not aware of any current attacks that can break the algorithm when it is used in HMAC-MD5 form with a randomly-chosen key.

The hole’s in the middle

The exploitable hole in the pseudocode above, therefore, isn’t in either of the lines where the hmac.md5() function is used.

Instead, the heart of the bug is line 11, where the data you want to authenticate is compressed into a fixed-length string…

.. by pushing it through a single invocation of plain old MD5.

In other words, no matter what HMAC function you choose in line 15, and no matter how strong and collision-resistant that final step might be, you nevertheless have a chance to cause a hash collision at line 11.

Simply put, if you know the data that’s supposed to go into the chksum() function to be authenticated, and you can use a collision generator to find a different block of data with the same MD5 hash…

…line 11 means that you’ll end up with exactly the same input value (the variable signdat in the pseudocode) getting pushed into the as-secure-as-you-like final HMAC step.

Therefore, even though you may be using a strong keyed message digest function at the end, you nevertheless might be authenticating an MD5 hash that was derived from imposter data.

Less would have been more

As Samba’s security bulletin compactly describes the problem:

The weakness […] is that the secure checksum is calculated as

HMAC-MD5(MD5(DATA),KEY), meaning that an active attacker knowing the plaintext data could create a different chosenDATA, with the same MD5 checksum, and substitute it into the data stream without being detected.

Ironically, leaving out the MD5(DATA) part of the HMAC formula above, which seems at first glance to increase the overall “mixing” process, would improve collision resistance.

Without that MD5 compression in the middle, you would need to find a collision in HMAC-MD5 itself, which probably isn’t possible in 2023, even with almost unlimited government funding, at least not within the lifetime of the network session you were trying to compromise.

What took so long?

By now, you’re probably wondering, as we were, why this bug lay undiscovered, or at least unpatched, for so long.

After all, RFC 6151, which dates right back to 2011, and has the significant-sounding title Updated Security Considerations for the MD5 Message-Digest and the HMAC-MD5 Algorithms, advises as follows (our emphasis, more than a decade later):

The attacks on HMAC-MD5 do not seem to indicate a practical vulnerability when used as a message authentication code. Therefore, it may not be urgent to remove HMAC-MD5 from the existing protocols. However, since MD5 must not be used for digital signatures, for a new protocol design, a ciphersuite with HMAC-MD5 should not be included.

It seems, however, because the vast majority of recent SMB server platforms have HMAC-MD5 authentication turned off, that SMB clients still supporting this insecure mode generally never used it (and would have failed anyway if they’d tried).

Clients implicitly seemed to be “protected”, and the insecure code seemed to be as good as harmless, because the weak authentication was apparently neither needed nor used.

So this potential problem simply never got the attention it deserved.

Unfortunately, this sort of “security by assumption” fails completely if you happen to come across (or get lured towards) a server that does accept this insecure chksum() algorithm during logon.

This sort of “downgrade problem” is not new: back in 2015, researchers devised the notorious FREAK and LOGJAM attacks, which deliberately tricked network clients into use so-called EXPORT ciphers, which were the deliberately-weakened encryption modes that the US government bizarrely insisted on by law last century.

As we wrote back then:

EXPORT key lengths were chosen to be just about crackable in the 1990s, but never extended to keep up with advances in processor speed.

That’s because export ciphers were abandoned by the US in about 2000.

They were a silly idea from the start: US companies just imported cryptographic software that had no export restrictions, and hurt their own software industry.

Of course, once the law-makers gave way, the EXPORT ciphersuites become superfluous, so everyone stopped using them.

Sadly, a lot of cryptographic toolkits, including OpenSSL and Microsoft’s SChannel, kept the code to support them, so you (or, more worryingly, well-informed crooks) weren’t stopped from using them.

This time, the main culprit amongst servers that still use this broken MD5-plus-HMAC-MD5 process seems to be the NetApp range, in which some products apparently continue (or did until recently) to rely on this risky algorithm.

Therefore you may still sometimes be going through a vulnerable network logon process, and be at risk from CVE-2022-38023, perhaps without even realising it.

What to do?

This bug has finally been dealt with, at least by default, in the latest release of Samba.

Simply put, Samba version 4.17.5 now forces the two options reject md5 clients = yes and reject md5 servers = yes.

This means that any cryptographic components in the various SMB networking protocols that involve the MD5 algorithm (even if they are theoretically safe, like HMAC-MD5), are prohibited by default.

If you really need to, you can turn them back on for accessing specific servers in your network.

Just make sure, if you do create exceptions that internet standards have already officially advised against for more than a decade…

…that you set yourself a date by which you will finally retire those non-default options forever!

Cryptographic attacks only ever get smarter and faster, so never rely on outdated protocols and algorithms simply “not being used any more”.

Strip them out of your code altogether, because if they aren’t there at all, you CAN’T use them, and you can’t be tricked into using them by someone who’s trying to lure you into insecurity.

Gary

I caught your HHGTtG reference there: ” until they turn into somebody else’s problem”. Well played sir.

Paul Ducklin

Might be an M.Sc. thesis in there somewhere (albeit from a non-accredited institution). “Visualising SEP field strength lines in real-time as a privacy and cybersecurity measure.”

I wrote a compass app for my GARMIN that is my primary navigation aid these days… maybe an SEP Field Detector could be next?

Norka Foraski

Great post, keep up the good work.

Paul Ducklin

Thanks. Glad you found it useful!

Anonymous

Typo

Any hashing algorithm that can BE reliably BE “cracked”

Get rid of one of the BEs

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks.