[Update (2022-06-30): Screenshots of commands and other log entries were replaced with less cluttered versions. IoCs related to this attack are now on the SophosLabs Github.]

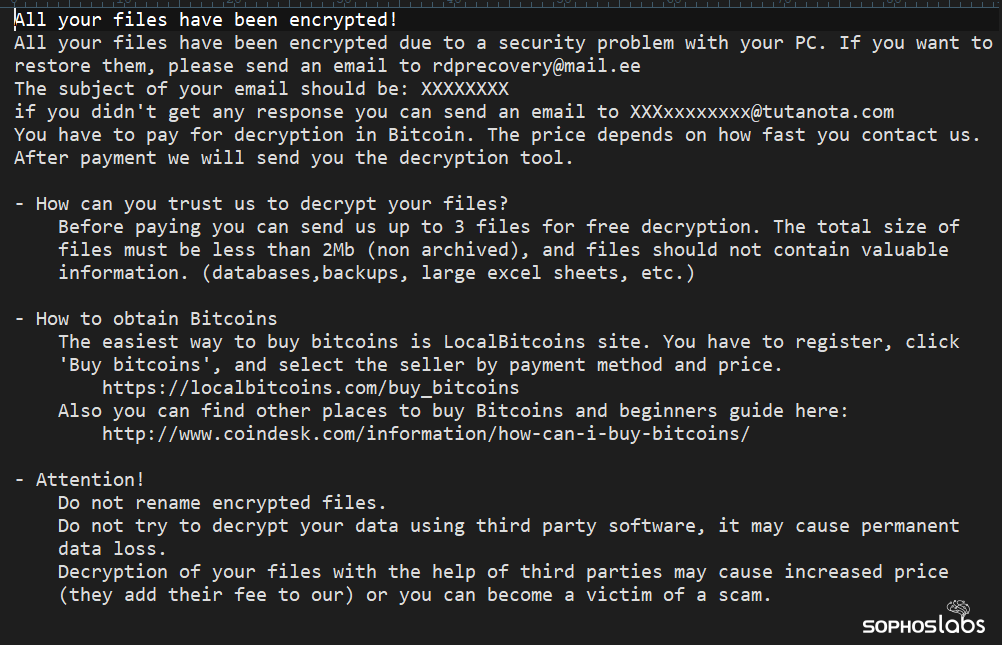

In an attack where unknown threat actor groups spent at least five months poking around inside the network of a regional US government agency, behavioral log data suggests that two or more such groups were active before the final group deployed a Lockbit ransomware payload earlier this year.

Throughout the period attackers were active on the target’s network, they installed, then used Chrome browser to search for (and download) hacking tools on the “patient zero” computer, a server, where they made their initial access. Though the attackers deleted many Event Logs from machines they controlled, they didn’t remove them all.

Sophos was able to piece together the narrative of the attack from those unmolested logs, which provide an intimate look into the actions of a not particularly sophisticated, but still successful, attacker.

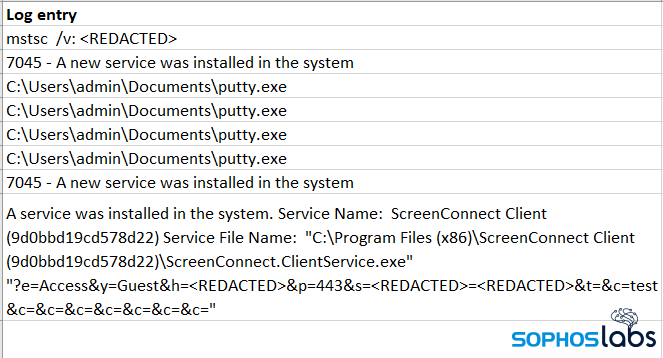

For instance, the logs recorded that the attackers installed various commercial remote-access tools on accessible servers and desktops. They appeared to prefer the IT management tool ScreenConnect, but later switched to AnyDesk in an attempt to evade our countermeasures. We also found download logs of various RDP scanning, exploit, and brute-force password tools, and records of successful uses of those tools, so Windows remote desktop was on the menu, too.

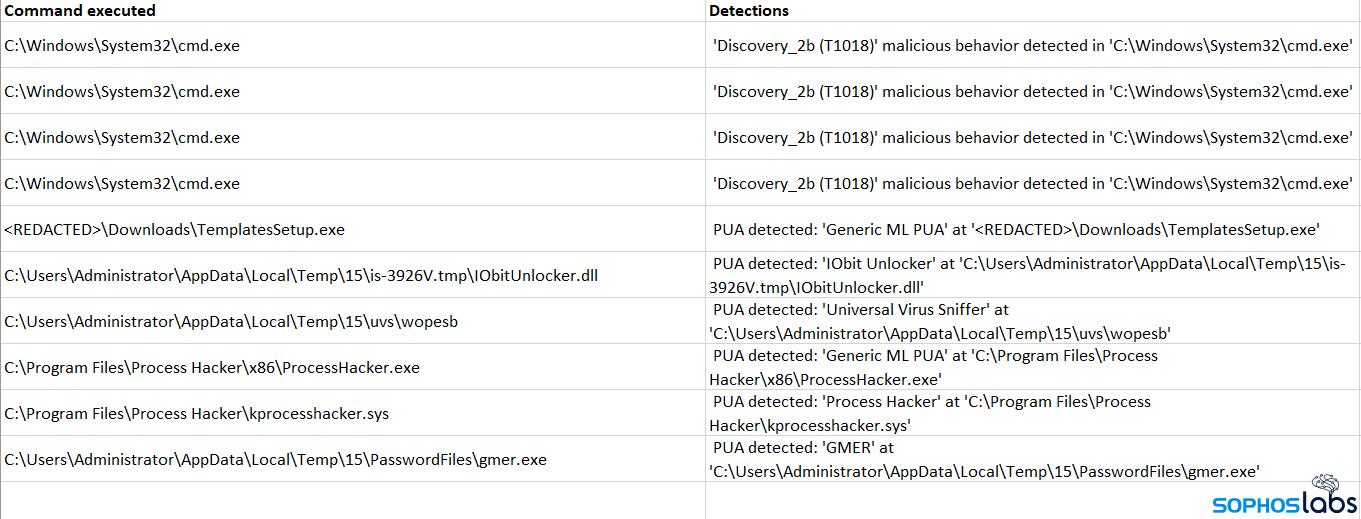

In addition to various custom scripts and configuration files used by hacking tools the attackers installed, we found a wide variety of other malicious software, from password brute-forcers, to cryptominers, to pirated versions of commercial VPN client software. There was also evidence the attackers used freeware tools like PsExec, FileZilla, Process Explorer, or GMER to execute commands, move data from one machine to another, and kill or subvert the processes that impeded their efforts.

Critically, technicians managing the target network left a protective feature disabled after they completed maintenance. As a result, some systems were left vulnerable to sabotage by attackers, who disabled endpoint protection on the servers and some desktops. With no protection in place, the attackers installed ScreenConnect to give themselves a backup method of remote access, then moved quickly to exfiltrate files from file servers on the network to cloud storage provider Mega.

Over time, we found that the attackers’ tactics changed, in some cases so drastically it seemed as though an attacker with very different skills had joined the fray. The nature of the activity recovered from logs and browser history files on the compromised server gave us the impression that the threat actors who first broke in to the network weren’t experts, but novices, and that they may later have transferred control of their remote access to one or more different, more sophisticated groups who, eventually, delivered the ransomware payload.

Reconstructing the attack from logs

Attackers will often delete log data to obfuscate their tracks, and this incident was no exception – the attackers manually deleted nearly all log data about a month prior to investigator discovery. However, a deeper forensic dig indicates that the initial compromise occurred nearly half a year before investigators opened their case. The method of ingress was nothing spectacular – open RDP ports on a firewall that was configured to provide public access to a server.

For a while, it was a relatively quiet invasion. The attackers got a lucky break when the account they used to break in over RDP was not only a local admin on the server, but also had Domain Administrator permissions, which gave it the ability to create admin-level accounts on other servers and desktops.

Reconstructed through searches of browser and application history logs that remained untouched, Sophos analysts were able to build a picture of a network ill-equipped to resist this type of attack, and attackers who seemed to have done little preparation for what to do beyond gaining initial access.

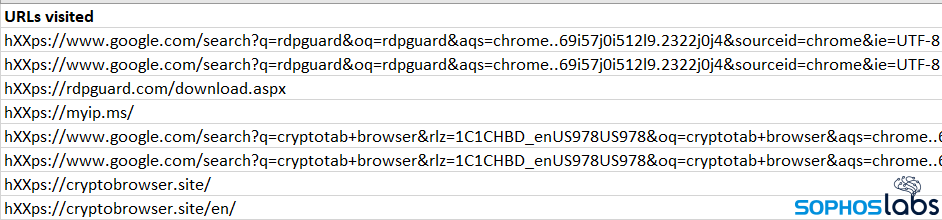

In the course of performing the post-attack analysis, Sophos analysts determined that the attackers used the servers they controlled inside the target’s network to perform Google searches for a variety of hacking tools.

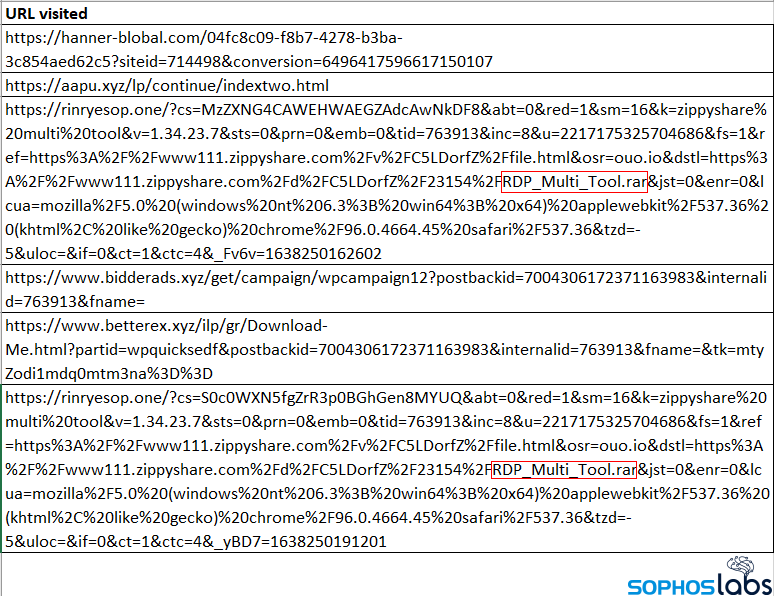

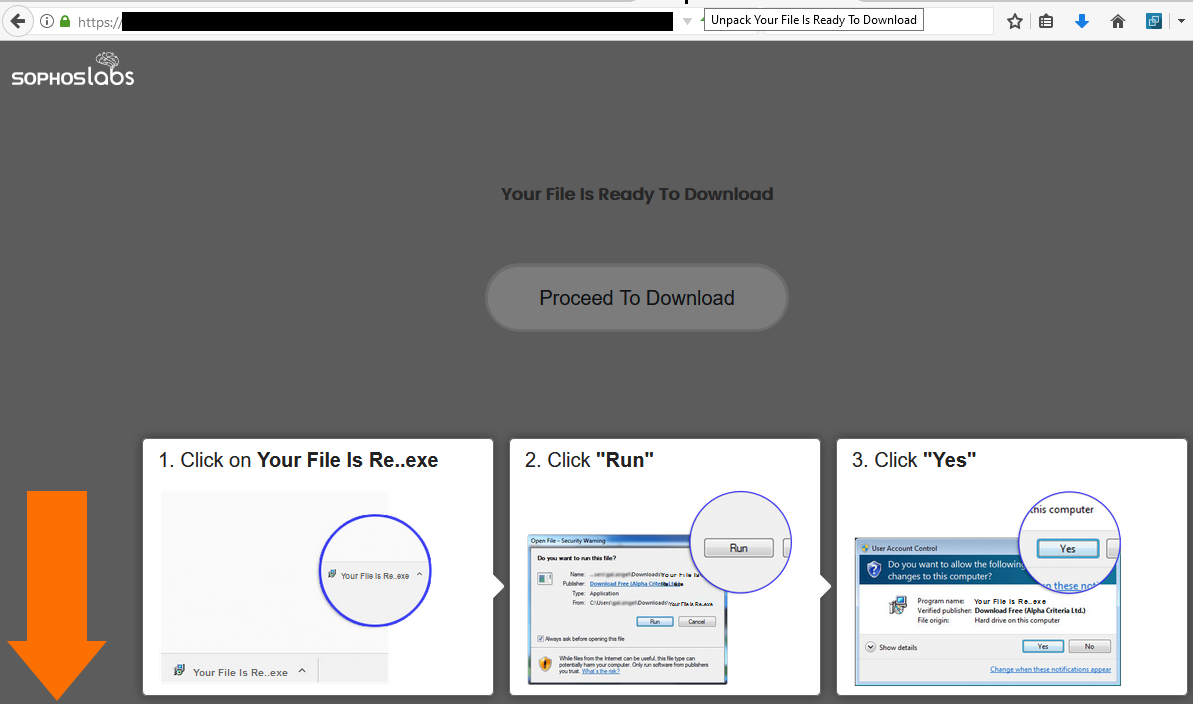

In some cases, following the search results for these tools led the attackers into a variety of shady download sites. The advertising networks whose banner ads appear on these sites appear to have generated popup ads that delivered a potentially unwanted app download as the attackers clumsily pulled together a selection of attack tools, further muddying the picture and leaving the server infected with adware, and the browser history cluttered with redirects.

The forensic traces left behind seem to paint a picture of a novice attacker doing a bit of on-the-job training – attempting tool installation (after Googling the tools), opening random text files, and running a surprising number of speed tests, but not moving toward a particular goal or operating with great urgency.

Surviving log data indicates the attacker would leave the server unbothered for days at a time, unexpectedly (and counterintuitively) during American holiday periods. When they were on the system, the attacker seemed to rely on a lot of the shady variety of public file-sharing services, whose advertisements mimic file download links or buttons in an attempt to entice visitors to click their ad instead of the real download button on the page – an ad that typically redirects the visitor into a rotating pool of sites pushing junkware.

Some of the evidence shows the attacker either inadvertently clicked one of these fake-download-button ads, or suffered from popup or popunder advertisements that pushed unwanted downloads at the attacker, who then installed the adware, perhaps thinking it was the real pirated copy of a hack tool they thought they were downloading. These unintentional self-infections created additional noise in the logs.

Unlike many threat actors who pre-configure attack scripts that, for instance, scan networks to determine a target list and then run those scripts to deliver payloads to internal machines, the attackers for months seemed content merely to poke around and occasionally create a new account on the initial, or another, machine. Some of the attacks originated from the Desktop folder of the user account the attackers initially compromised, but others involved admin-level accounts the attackers created with names like ASP.NET or SQL.NET.

Pivot to a more serious attack

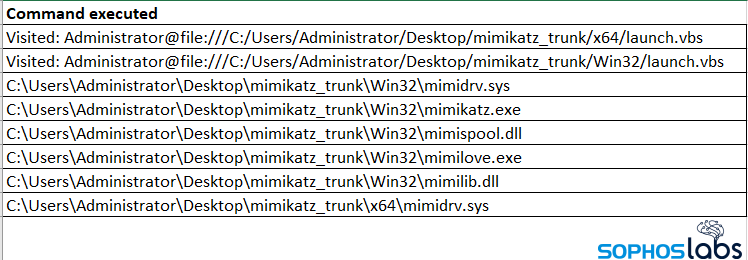

In the fifth month of the infiltration, however, the attacker behavior dramatically changed. After a three-week hiatus, logs indicate that an attacker remotely connected and installed the password-sniffing tool Mimikatz. Sophos protections saw it happen, and cleaned a first attempt at infection. Unfortunately, the IT department didn’t heed the warning, and the attacker’s later attempt to run Mimikatz via a compromised account was successful. (The attackers also attempted to gather credentials using a different tool called LaZagne.)

The credential-dumping application did its work, and within a couple of days, the attackers had a password.txt file sitting on the desktop of the admin-level accounts they’d created on the compromised server. This marks a turning point of sorts in the investigation; at this point, one must assume that any account that had logged into the troubled server was indeed compromised, credentials exposed.

And something else happened: On the same day the passwords.txt file appeared, someone decided to do a bit of tidying up. The initial threat actor, or a newer threat actor, visited websites looking for instructions to uninstall a malicious coinminer that, earlier, had been installed on the beleaguered server.

Scouring log data is a conventional move for an attacker, even one with less dwell time than the attacker in this case. Wiping logs eliminates useful forensic information about the intrusion. The attacker used a compromised account to clear the WitnessClientAdmin, Windows PowerShell, and System logs. By the end of the attack, no event logs prior to about five weeks before the end would be available on the system.

The attacker also spotted the Sophos endpoint installation and tried (unsuccessfully) to remove those as well, using a variety of tools like GMER and IOBit Uninstaller. Via yet another compromised account, the attacker(s) installed an assortment of popular brute-force and proxy tools including NLBrute.

A partial list of maliciously used tools discovered on the compromised system includes the following. It should be noted that not all of these are inherently malicious tools, nor are they all surprising to find on healthy, uninfected machine.

| Advanced Port Scanner | Scans to find network devices |

| AnyDesk | Remote desktop application |

| LaZagne | Allows users to view and save authentication credentials |

| Mimikatz | Allows users to view and save authentication credentials |

| Process Hacker | Multipurpose tool for monitoring system resources |

| Putty | Terminal emulator, serial console, network file transfers |

| Remote Desktop Passview | Reveals passwords stored in an .rdp file by Microsoft’s RDP utility |

| ScreenConnect | Remote desktop application |

| SniffPass | Password monitoring tool; listens on the network adapter |

| WinSCP | SFTP/FTP client for copying files between local and remote machines |

Suddenly – over four months after the initial compromise — not only are the behaviors of the attackers suddenly crisper, more focused, but the locations of the malicious visitor(s) have expanded, with IP-address traces indicating connections from both Estonia and Iran. Ultimately the compromised network would host malicious visitors from IP addresses that geolocate to Iran, Russia, Bulgaria, Poland, Estonia, and… Canada. But these IP addresses may have been Tor exit nodes.

Ironically, right around this time, the target’s IT department noticed that the systems were “acting strange” – repeatedly rebooting, possibly by the threat actor’s direct command shortly after destroying the event logs. The IT department began its own investigation and would ultimately take five dozen servers offline while they built network segmentation designed to protect known-good devices from the others. However, to cut down on distractions, the IT department disabled Sophos Tamper Protection.

Things got frenetic after that. The last ten days of the infection were full of moves and countermoves made by the attackers and the IT department. On the eighth day, Sophos’ team entered the fray. Through the end of the last calendar month of the attack, a steady stream of table-setting activities took place as the attackers dumped account credentials, ran network enumeration tools, checked their RDP abilities, and created new user accounts, presumably to give themselves options in case they were interrupted in subsequent attacks. The logs were wiped multiple times and machines restarted during this period.

On the first day of the sixth month of the attack, the attacker made their big move, running Advanced IP Scanner and almost immediately beginning lateral movement to multiple sensitive servers. Sophos protections knocked down several new attempts at malicious file installation, but compromised credentials allowed the attacker to outflank those protections.

Within minutes, the attacker(s) had access to a slew of sensitive personnel and purchasing files, and attackers were hard at work doing another credential dump.

The next day, the target engaged with Sophos. Labs analysts identified the 91.191.209.198:4444 as a phone-home address with related shellcode, now detected as ATK/Tlaboc-A and ATK/Shellcode-A. Over the course of several days, the IT team and Sophos analysts collected evidence then quickly shut down servers that provided the attackers with remote access, and worked to remove the malware from the machines that had not been encrypted.

Fortunately for the target, on at least a few machines, the attackers didn’t complete their mission, as we found files that had been renamed with a ransomware-related file suffix, but that had not been encrypted. Cleanup in those cases just involved renaming the files to restore their previous file suffixes.

Guidance and detection

In the course of the investigation, one factor seemed to stand out: The target’s IT team made a series of strategic choices that enabled the attackers to move freely and to access internal resources without impediment. Deployment of MFA would have hindered the access by the threat actors, as would a firewall rule blocking remote access to RDP ports in the absence of a VPN connection.

Responding to alerts, or even warnings about reduced performance, promptly would have prevented a number of attack stages from bearing fruit. Disabling features like tamper protection on endpoint security software seemed to be the critical lever the attackers needed to completely remove protection and complete their jobs without hindrance.

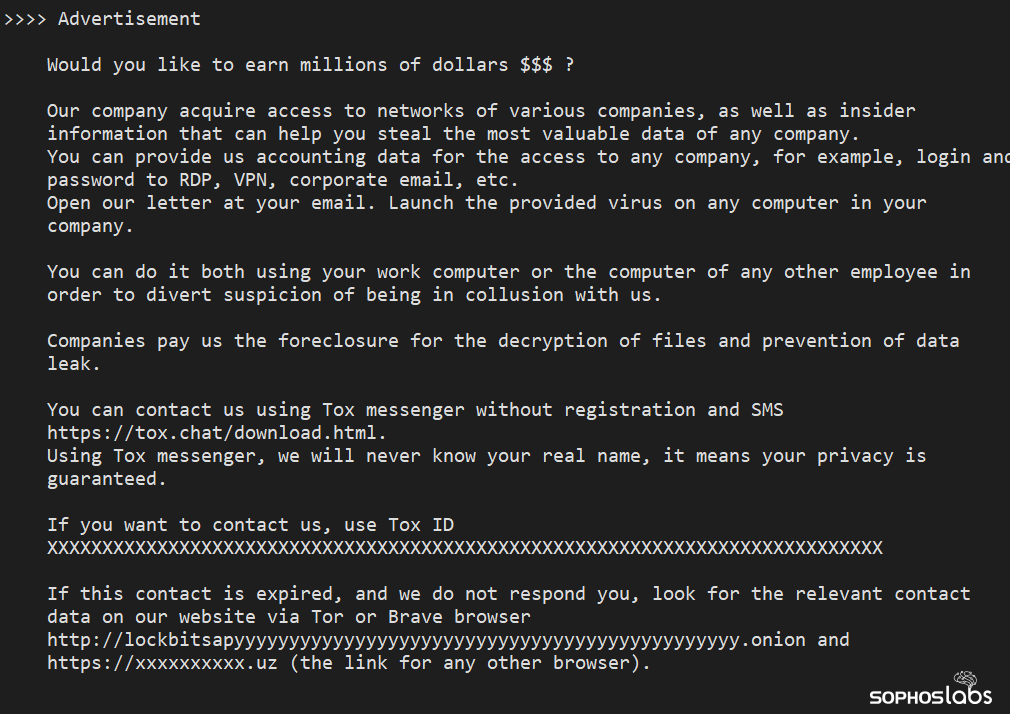

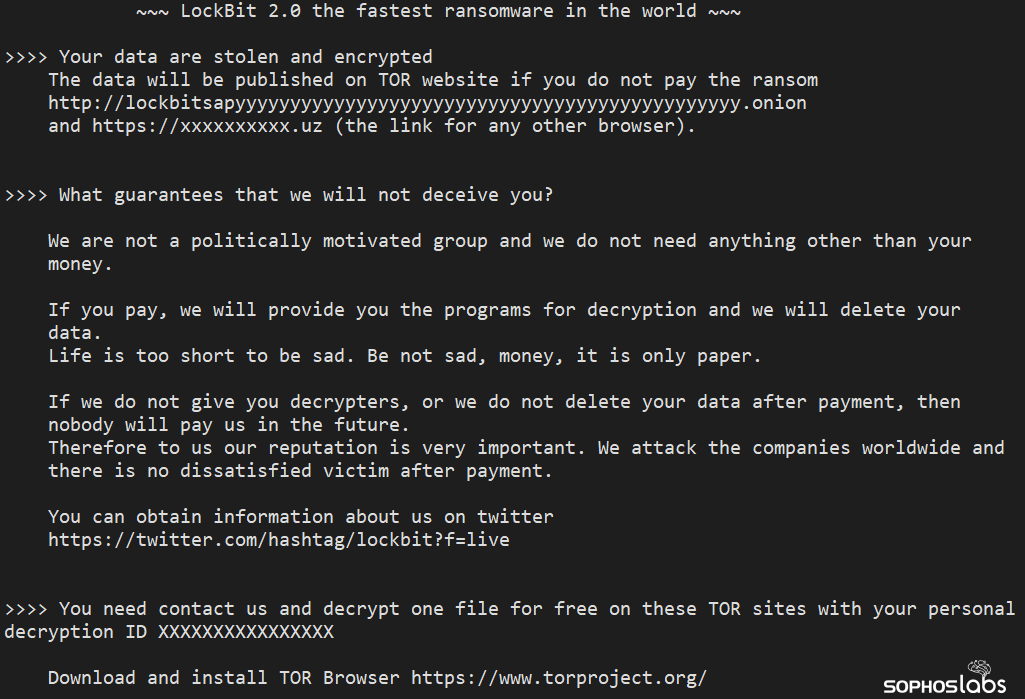

The ransomware threat actors added a help wanted ad into their ransom note. Our recommendation is that insiders with access to sensitive information refrain from committing crimes by helping ransomware threat actors.

The ransomware binaries deployed in this attack are detected using CryptoGuard. Not all of the various dual-purpose attack tools used in the attack are routinely detected, as many of these utilities have a legitimate IT administrative purpose.

All other shareable IOCs relating to this attack have been uploaded to the SophosLabs Github. Sophos only shares indicators and samples which cannot be tied to a specific target to protect the target’s privacy.

Acknowledgments

SophosLabs would like to acknowledge the contributions of analysts Melissa Kelly, Peter Mackenzie, Ferenc László Nagy , Mauricio Valdivieso, Sergio Bestulic, Johnathan Fern, Linda Smith, and Matthew Everts for their work reconstructing the attack.