Over the past two months or so, Mozilla’s Firefox browser has had a lot less media attention than Google’s Chrome and Chromium projects…

…but Mozilla probably isn’t complaining this time, given that the last three mainstream releases of Chrome have included security patches for zero-day security holes.

A zero-day is where the crooks find an exploitable security hole before the good guys do, and start abusing that bug to do bad stuff before a patch exists.

The name reflects the annoying fact that there were zero days that you could possibly have been ahead of the crooks, even if you are the sort of accept-no-delays user who always patches on the very same day that software updates first come out.

To be fair to the Chromium team, the most recent zero-day hole, patched in version 90 of the Chrome and Chromium projects, is best described as half-a-hole. You have to go out of your way to run the browser with its protective sandbox turned off, something that you will probably not do by choice, and are unlikely to do by mistake.

What’s in a name?

Happily, this month’s Firefox update (actually, Mozilla’s updates come out every four weeks, always on a Tuesday, rather than once a calendar month) has attracted attention more for a new privacy feature it has included than for the security holes it has removed.

The “problem child” that Firefox just addressed is a lesser-known JavaScript variable called window.name.

When a browser page opens a new window or tab, it can give that new page a name (a tag or a moniker, if you like), by which to refer to the new tab later on as a target for opening additional content.

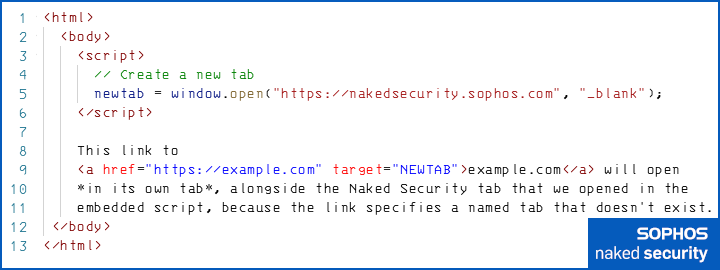

Here’s an example of a legitimate use for the window.name property.

In our first attempt, we’ve referred to the target tab NEWTAB in the link on our page, and we’ve created a new tab using window.open(), but we haven’t set a window.namevalue for the new tab:

We get a page with the Naked Security site in a second tab, together with a link in the first tab to to open a third site, namely example.com:

However, because we haven’t set a window name for either of the two tabs already open, our link just opens in a third tab of its own, sandwiched between the previous two:

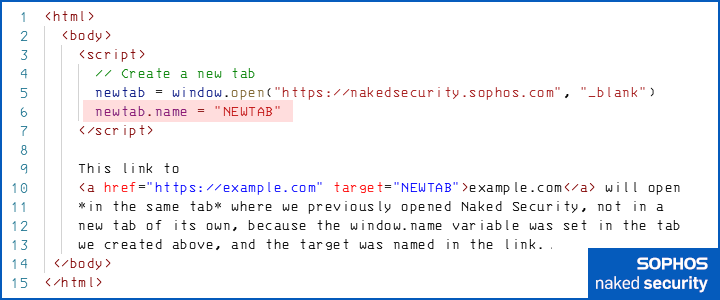

Let’s make a small change and try again.

This time, we’ve included a line of JavaScript to set the name property of the Naked Security tab when we open it, so we can explicitly reference that second tab in the future, using the moniker NEWTAB:

The main tab looks similar to last time:

Specifying an existing tab name in the target of the link means that we can re-use the second tab for our new content, so that the example.com page opens up in the same NEWTAB tab, replacing the Naked Security content and avoiding the creation of a third tab.

We end up with just two tabs, not three like last time:

This sort of behaviour can be useful in content management systems where you want a single “preview” page that keeps getting updated as you edit your content, rather than leaving you with a new open tab for every page you preview.

Window names considered harmful

Unfortunately, the window.name property doesn’t follow the so-called Same-Origin Policy (SOP), where only cookies and JavaScript variables set by website X can be read back in by website X.

The SOP is a fundamental part of web security, because it stops site Y, which might be an unscrupulous marketing page or a phishing site run by crooks, from getting at personal data stored by site X.

After all, data commonly stored in site-specific JavaScript variables or cookies can include details such as your username, your login secret (effectively the password for the current session), your profile and preferences, the current contents of your shopping cart, and much more.

So the SOP exists not only to stop personal web data from leaking inadvertently between different websites, but also to stop companies from sneakily tracking you by sharing data via innocent-looking JavaScript variables that you wouldn’t otherwise worry about.

And the window.name value was, at least until Firefox 88, one of those innocent-looking but open-to-abuse JavaScript settings.

The window.name property could surreptitiously be misused to bypass the SOP because it didn’t get cleared between different sites.

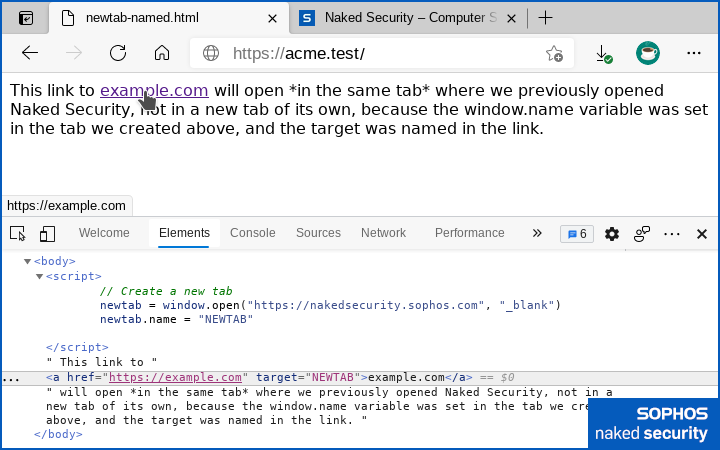

We can see that behaviour for ourselves, using the handy developer tools in the current [2021-04-20T13:00Z] version of Edge (based on Chromium).

Here, we’ve opened the special web page about:blank, which is simply an empty HTML page with a domain name that won’t match any other website, and we’ve used the JavaScript console to set the window.name variable to the value pass-it-on-to-the-next-site:

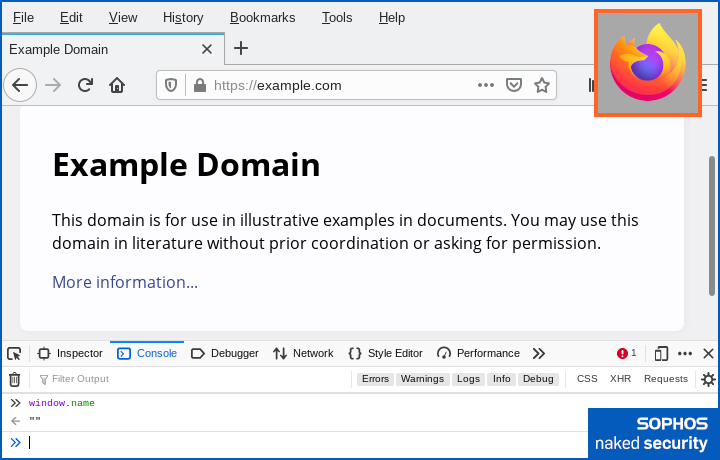

Now, we’ve opened up a page from a completely different domain, namely example.com, yet we can see that the old value of window.name has been carried through to the new page, even though you might expect the Same-Origin Policy to prevent that from happening:

In other words, the unassuming window.name variable can be used as a sneaky way of passing messages between different domains, bypassing the SOP, and therefore sharing tracking codes from site to site when you would not expect it.

Exploited for years

According to Mozilla, web tracking companies have been exploiting this loophole for years:

Since the late 1990s, web browsers have made the window.name property available to web pages as a place to store data. Unfortunately, data stored in window.name has been allowed by standard browser rules to leak between websites, enabling trackers to identify users or snoop on their browsing history. […]

Tracking companies have been abusing this property to leak information, and have effectively turned it into a communication channel for transporting data between websites. Worse, malicious sites have been able to observe the content of window.name to gather private user data that was inadvertently leaked by another website., and has decided to put a stop to this.

From Firefox 88 onwards, things have changed:

To close this leak, Firefox now confines the window.name property to the website that created it.

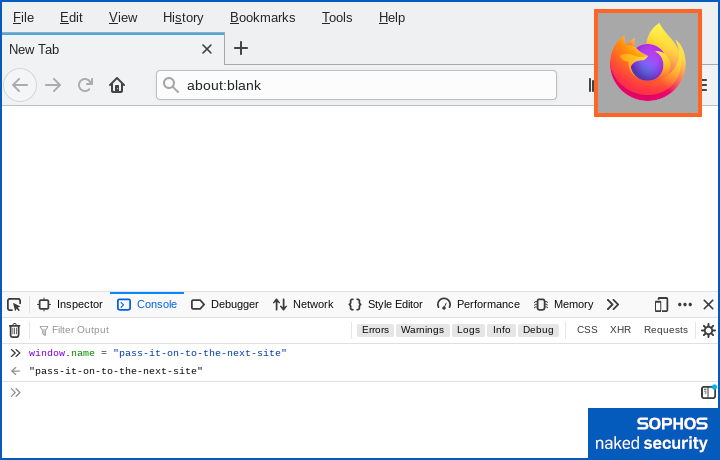

Here’s the difference – we repeated the above activity in the developer console, this time using the new Firefox 88.

Like before, we set the window.name property when our domain name was about:blank:

But when we switched to example.com, the value from before had been wiped out, and the window.name variable came back as an empty string:

In even better news, Mozilla reports that the other mainstream browser platforms are making the same sort of change, thus removing this tracking trick across the board:

Firefox isn’t alone in making this change: web developers relying on window.name should note that Safari is also clearing the window.name property, and Chromium-based browsers are planning to do so. Going forward, developers should expect clearing to be the new standard way that browsers handle window.name.

It’s a small change, to be sure, but it’s nice to see the browser makers agreeing to chip away in unison at “features” of this sort that are easily abused by websites that don’t care about privacy.

Lots of bug fixes

As you’d expect from a four-weekly Firefox release, there are also numerous security fixes in the 88.0 version.

None of them are rated critical, presumably because no one has yet figured out how to turn the more dangerous looking bugs into actual, working exploits.

Nevertheless, several of the bugs deal with potentially dangerous and exploitable mismanagement of memory, including a buffer overflow (where you write to the wrong part of memory) and two use-after-free bugs (where you write to memory that has already been turned over for use elsewhere).

Following Mozilla’s usual terminology, the Firefox developers have documented all these bugs with an admission that “we presume that with enough effort some of these could have been exploited to run arbitrary code.”

Rather than wait until someone – hopefully a cybersecurity researcher willing to disclose new exploits responsibly, rather than simply to sell them on the open market – proved that the bugs really were dangerous, the team patched them anyway.

Other bugs patched included so-called “presentation” bugs, where a user might think they were on site X when they weren’t.

As you can imagine, phishers love this sort of bug because it helps them to pass off fake content as real, even to users who are keeping an eye out to ensure they are on the website they expect.

What to do?

If you’re on Windows or Mac, go to Help > About Firefox or to Firefox > About and check if you are up-to-date.

If you aren’t, doing the version check will offer to do the update for you right away.

If you’re on Linux, your Firefox version may be managed as part of your distro, so Help > About may simply show you the version you are on, without doing an explicit update check. (As at 2021-04-20T13:00Z, you are looking for Firefox 88.0.)

Check back with your distro’s package manager to get the latest version.

On iOS and Android, you can update from the App Store or Google Play respectively, but note that on an iPhone, Firefox uses Apple’s browser core (which won’t yet have the window.name fix), and on Android, the latest version number may vary from device to device.

Bryan

Interesting. As a not-a-web-dev, I didn’t know about window.name…but will keep it in mind when working hobby projects.

Good article. Nice to hear some good news as well–when the “What To Do” section is primarily check for hte latest patch and keep fighting the good fight.

Thanks Duck!

couple typos: inadvetently, outselves, reposnsibly

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks!

turbostar

Paul,

“None of them are rated critical, presumably because no one has yet figured out how to turn the more dangerous looking bugs into actual, working epxloits.”

Just a typo on the last word.

thanks.

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks!

Jack

Odd question perhaps, but why did it take so incredibly long to ‘fix’ this?

I mean, they knew it was being exploited for many years, not that it suddenly got used for exploits within the last couple of months. Makes it look like there was a major benefit to having it around, from a non-programming point of view.

Paul Ducklin

I guess it was one of those “features” that was sufficiently widely used for non-bad purposes that removing it had to be discussed and negotiated and only eventually take care of.

Lots of “obvious” cybersecurity fixes turn out to be really hard to deploy because they end up “breaking” legitimate features in widely used apps or websites that could have (*should* have!) been coded better in the first place, or could have (*should* have!) been updated or replaced years ago, … but weren’t.

For example, you should see how long it takes to retire old encryption algorithms once we know they aren’t secure, or when much better ones come along :-( Or how long it took to persuade people they no longer needed Flash in their browser, or to convince them that, yes, there is a perfectly happy life beyond Windows XP.

Len

Hovering over an eBay image is failing to zoom it although it works ok in other browsers?