(This blog post is a condensed summary of the report Baldr vs The World. – ed.)

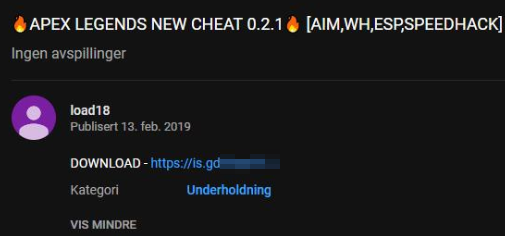

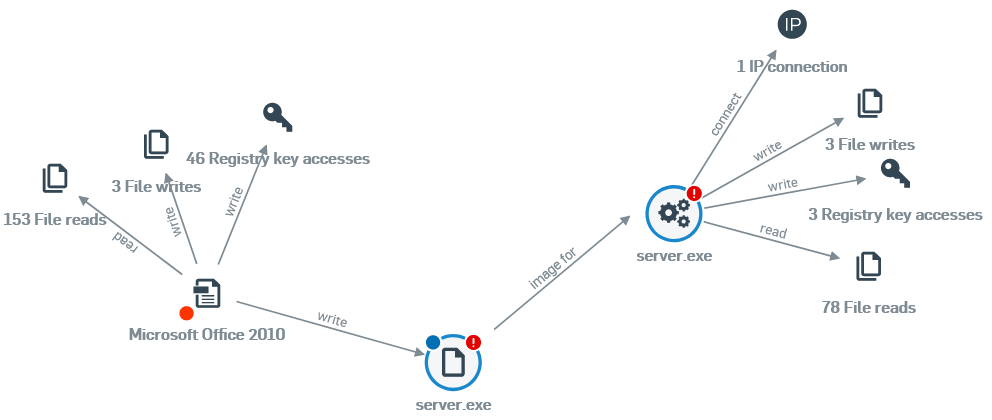

The videos touting cheat utilities for games like Apex Legends and Counter Strike: Go started to appear on YouTube in February. The malspam came later, using .ace archive files modified to exploit a longstanding vulnerability in a rarely used component of the WinRAR compression utility. Still later, different rounds of malspam started flowing, with RTF document attachments that employed an exploit against the Microsoft Office Equation Editor when opened.

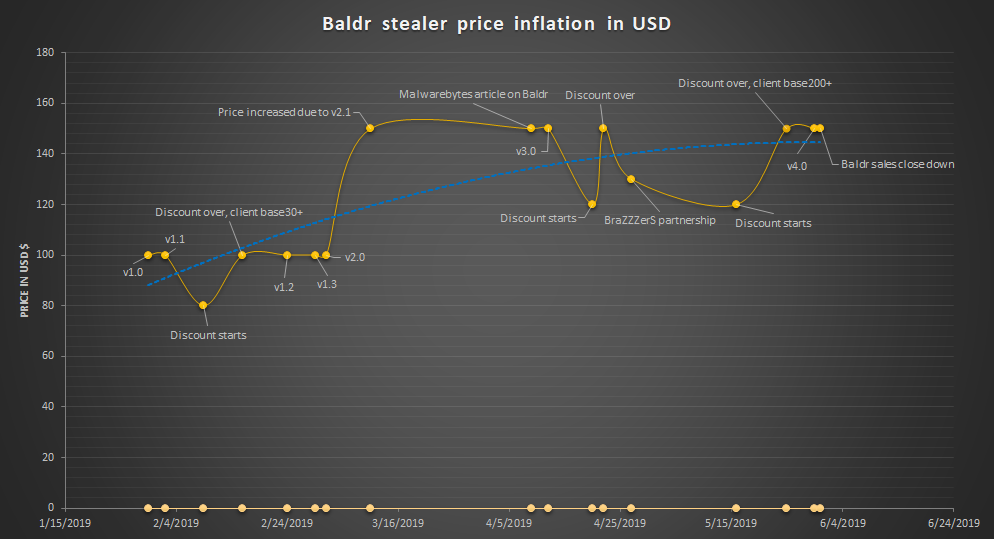

From this variety of sources came the same payload: A crimeware tool its creator named Baldr. Originating in crimeware web forums in January, 2019, Baldr is a small time upstart malware that since the beginning of this year, aggressively markets itself using frequent discounts and special deals. Purchasing a license to use Baldr gave a criminal permission to obtain and use every subsequent release free, forever. And they bought it.

By mid-April, Baldr’s principal reseller boasted that he has more than 200 customers who were actively using this came-out-of-nowhere malware in their campaigns. Clearly it was effective at its job, which is to scrape and steal any credentials, cookies, or cached data of resellable value in a matter of seconds.

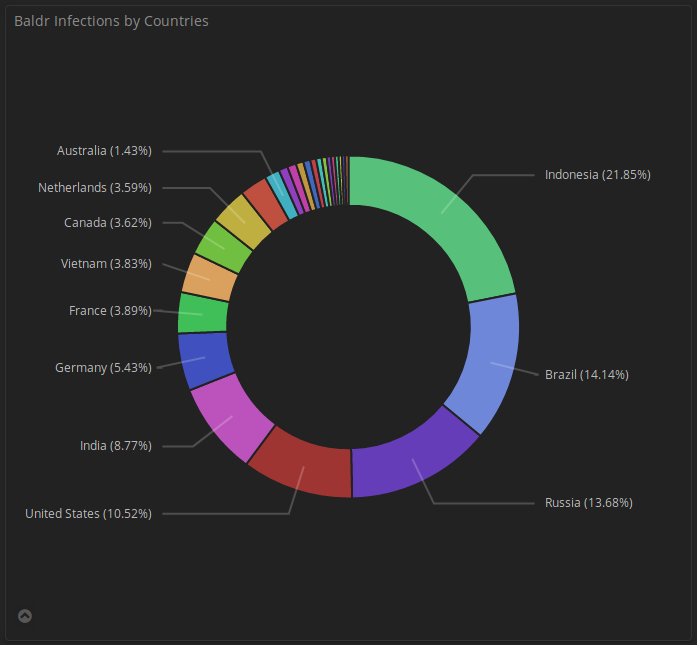

It did so in certain countries more than others. Asia and, in particular, Indonesia, at a bit over 21% of the victim population, was the most heavily infected country, followed in decreasing percentage of victims by Brazil (14.14%), Russia (13.68%), the United States (10.52%), India (8.77%), and Germany (5.43%).

Baldr is a standalone malware with a limited, targeted mission. It does not remain active once it scours the infected machine for saved data it can exfiltrate, which it does rapidly, and then quits. It does not use a mutex to check whether another copy is running. It does not contain any native way to establish persistence on the infected machine, other than by copying itself into the Start Menu’s Startup folder, so it runs every time the computer reboots. It does not sniff traffic or perform man-in-the-browser password theft like Trickbot.

It’s not feature rich, but what it does, it does quickly, and the criminal underground snapped it up.

What Baldr does

Upon execution, the malware compiles a detailed profile of the infected machine and its characteristics. It queries the \Uninstall path in the Windows registry to determine the full list of installed software on the computer it infects. And then it begins stealing.

Baldr knows how to steal saved passwords from 21 different Web browsers. Chrome, of course, but also Firefox, and Edge…and Opera, Brave, Waterfox, Yandex Browser, and Pale Moon, among many others.

It can and does dump out saved payment card data, the browser history, cookies, and the list of autocomplete terms that populate because you’ve typed them into forms yourself, just for good measure.

It knows where to look for the passwords saved by any email client software; for Jabber/XMPP instant messaging and FTP client passwords; for the passwords saved for game store software like Steam, Epic, or Sony, and for gaming-adjacent services like Twitch TV or Discord. It also knows where the clients for both ProtonVPN and NordVPN, two of the most popular private VPN services, store the credentials and configuration files, and it takes them, too. Of course it knows how to steal your bitcoin stash from any of 14 different wallet applications. It would be crazy not to.

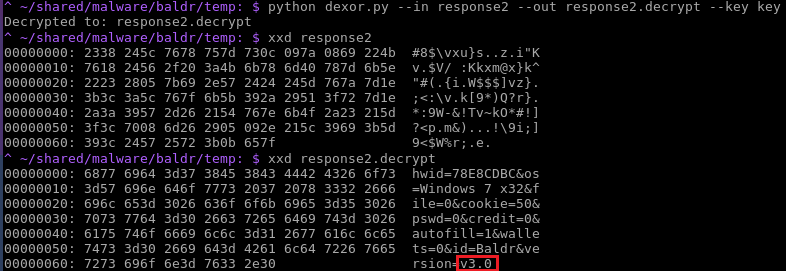

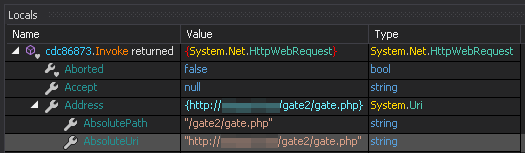

Once Baldr gathers all this information, the malware takes a screenshot of the desktop (just for good measure), compresses all the data into one file, encrypts the file, and sends it to its command and control server. It performs an HTTP POST to the C2 server and, if the malware’s operator enables certain features, the server will send instructions back as a reply.

In some infection scenarios, the C2 instructions have included a rudimentary persistence mechanism: the malware is instructed to copy itself into the Startup folder, where it will run again at the next reboot. The server can also transmit whole malware files back to infected machines in its response, effectively rendering Baldr a malware beachhead for other payloads.

The server’s address is hardcoded into the malware binary, but the criminals who use Baldr aren’t worried about services like ours discovering their C2 server address and getting the domain shut down, because they use bulletproof hosting services, which place the C2 software on multiple physical machines located at different IP addresses, which are used in conjunction with fast flux DNS pointing to the C2 domain. Those domains need to remain accessible if the criminal doesn’t know when the victim’s next reboot will happen.

The campaigns are in and out so quick, many of Baldr’s customers don’t even need to pay for the bulletproof hosting they use, because they can complete an entire campaign in less time than the free trial periods these services offer new customers. The sellers hawking Baldr helpfully refer their customers to several bulletproof hosts.

Control Panel Blues

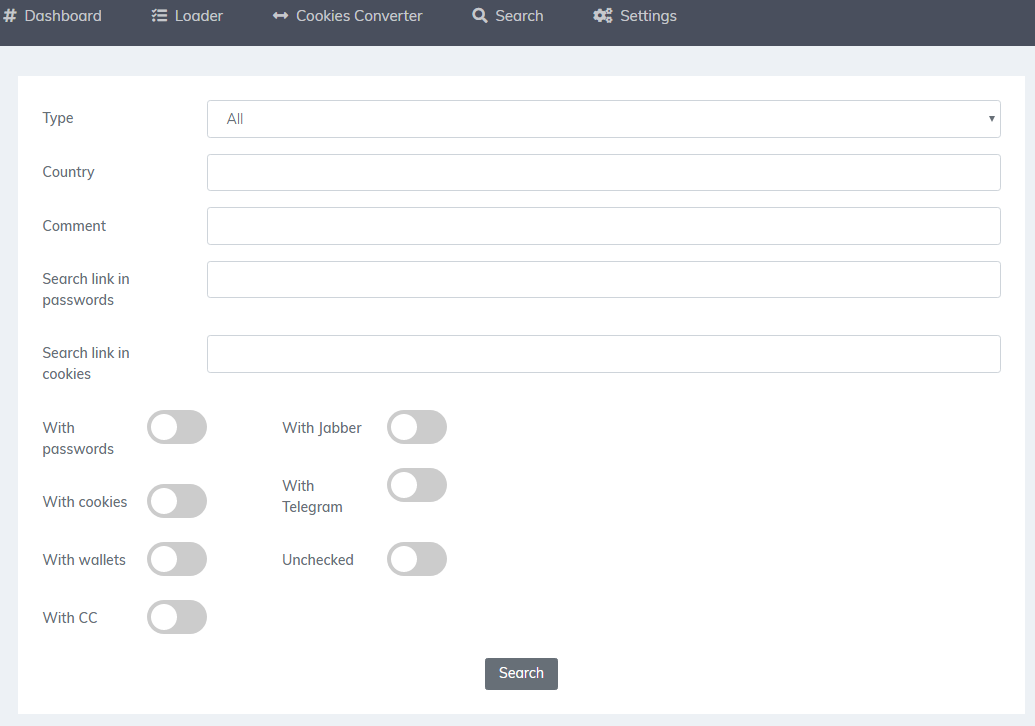

As a standalone malware that has no cloud management functionality, Baldr necessarily comes with its own command-and-control server software. The criminal who buys Baldr sets this up on the domain hosting service of their choice. It’s a slick looking panel with round switches and large text entry fields, and buttons to turn on or off certain features. In short, it looks like a lot of them.

The panel also serves as an information hub for the exfiltrated data sent back by Baldr, giving the criminals an opportunity to make a first skimming pass of the goods before saving that data in a format the criminal can then resell through carder forums.

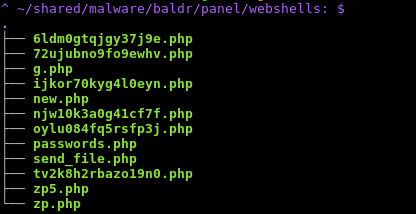

But there have been some notable opsec failures by crooks operating Baldr campaigns. Several of these criminal masterminds misconfigured their server and permitted anyone to browse an open directory housing the server files.

In a handful of cases, we found a zip file in the root of the C2 directory that contained the entire c2 server package, as well as the malware executables with their hardcoded domain names.

But misconfiguration isn’t the only problem plaguing Baldr customers. The C2 page itself contains multiple vulnerabilities, some of which had already, apparently, taken advantage of by other criminals to install web shells on the c2 server. In an Inception of pwnage, we found multiple different web shells on the same Baldr C2, some only a few hours old when we saw them. Anyone who used one of these web shells likely had access to the exfiltrated data stored on the server.

Baldr’s MalPals

Baldr was only one of several malware families that were being sold by a small team of vendors on a handful of sites that cater to this type of criminal. We infiltrated several of the sites and kept screenshot records of important conversations, feature notes, and sale details over the course of our investigation.

Baldr’s reseller also sold other malware, and often touted Baldr’s capability to deliver other malware in addition to rapidly draining it of any useful information. In sandbox tests over several months, we observed instances of Arkei or Megumin dropping Baldr during an infection, and Baldr dropping Megumin. That makes sense, as Baldr’s primary distributor also sells Megumin. We also saw some cases of Baldr delivering ransomware after data-scraping a victim.

But, caveat emptor, criminals who buy Baldr. The malware contains chunks of code copied straight out of other malware families. Functions used by Baldr to grab FileZilla and Telegram data mimic the subroutines in another credential thief, GrandStealer. The cookies converter function on Baldr’s c2 control panel is a precise match from Azorult’s panel: the same Javascript code is responsible for the conversion. “Gate.php” is used by a huge number of malware families as a c2 destination. None of it is, exactly, original. Baldr is a Frankenstein’s monster of code bits from other malware.

That doesn’t make it any less dangerous, of course. It’s just less boutique than the sellers would lead one to believe. It also doesn’t make it better.

Ground zero

In the course of investigating the story that makes up our Baldr vs The World report, we detected someone testing their sample of Baldr against Sophos Antivirus and HitmanPro 3.8. That’s great, and it gave us a lot of telemetry data about Baldr’s behavior and killchain. The criminals used stolen credit cards to pay for the licenses, which we refunded back to those card holders.

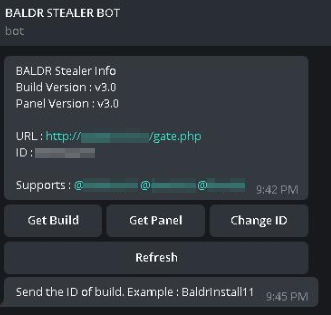

Baldr’s preferred method of customer service was to have chatbots on the instant messaging platform Telegram, who would answer inquiries and provide automated customer license management tasks. Customers make payments in one of several supported cryptocurrencies or alt coins.

But as Baldr ticked over to the six month mark after its creation, a surprise twist. Baldr’s principal reseller suddenly announced, with no warning that Baldr was no longer available for sale. The existing c2 servers and licensees could continue to use the service, but there would be no new sales.

The question of whether Baldr will come back remains up in the air. We suspect that, with as much work that went into Baldr in such a short time, it may be only a little while before its creator, and Baldr (or its successor), resurfaces. We’ll be watching.

IoCs and hashes relating to this investigation will be made available on the SophosLabs Github.

The author wishes to thank Gabor Szappanos and Fraser Howard for their contributions to the research.