In our recent Active Adversary report on trends we’ve seen over the past year, Sophos X-Ops flagged the remarkable increase in median “dwell time” – the amount of time attackers spend in a system before they’re removed (or even noticed). A portion of that increase is due to the rise of initial access brokers (IABs) – services that handle the work of getting a foothold on a victimized system, learning what’s available on it, and stealing relevant cookies and other identifiers. IABs make their money by gaining and maintaining access until they can sell it to other criminals. It’s another sign of the growing professionalization and specialization of the cybercrime sphere.

Genesis Marketplace is one of the earliest full-fledged IABs, and certainly one of the most polished. Here’s how it works.

Portrait of an IAB

Genesis – called Genesis Marketplace, or Genesis Store, or Genesis Market; the site refers to itself inconsistently – is an invitation-only marketplace. It sells stolen credentials, cookies, and digital fingerprints that are gathered from compromised systems, providing not just the data itself but well-maintained tools to facilitate its use.

Genesis has been active since 2017 and currently lists more than 400,000 bots (compromised systems) in over 200 countries. Italy, France, and Spain lead the list of affected nations. The attacker appeal of Genesis’ collection isn’t the size of its data aggregation; it’s the quality of the stolen information that Genesis offers and the service’s commitment to keeping that stolen information up to date.

(The word “bot” in this situation might not be the usage a casual infosec observer would expect. Genesis and similar marketplaces use the term “bot” for individual compromised systems; in this case it refers specifically to the credential-harvesting, home-phoning automated malware on the compromised system. Persistent bots on victims’ systems enable Genesis to tout the fact that once customers pay for stolen information, Genesis will keep that information updated as it changes over time.)

Genesis claims that as long as it has access to a compromised system, that system’s fingerprints will be kept up to date. In other words, Genesis customers aren’t making a one-time buy of stolen information of unknown vintage; they’re paying for a de facto subscription to the victim’s information, even if that information changes. This makes the stolen data Genesis sells more useful for attackers and thus more valuable.

Rounding out the dark appeal of Genesis are several customer-service features that let bad actors concentrate on doing crimes, not tech: A polished interface with good data-correlation capabilities; effective and well-maintained tools for customers, including a robust search function; and mainstream accoutrements such as an FAQ, user support, pricing in dollars (though payment is in Bitcoin), and competent copyediting.

The Customers

Who are Genesis’ customers? IABs attract criminals looking to expedite infiltration into, and lateral movement within, a targeted system. Speeding up those steps reduces the time required to attack effectively, and it minimizes detection by processes that look for certain kinds of suspicious movement. One side effect of the rise of IABs? A net increase in dwell time on compromised systems – the most interesting data trend we saw in our 2022 report on active adversaries.

While it’s often difficult to ascertain exactly who purchases data and access from IABs, ransomware groups and affiliates are frequent customers. The most common tactic attackers carry out with data of this sort is credential stuffing, in which stolen credentials are used to bombard a targeted service or business in an attempt to gain access. Using fingerprint data rather than simple stolen user ID / password combos to do a credential-stuffing attack helps attackers mask the fact that the onslaught is coming from a single point. This can help attackers bypass specific countermeasures sites have put in place to prevent credential stuffing attacks.

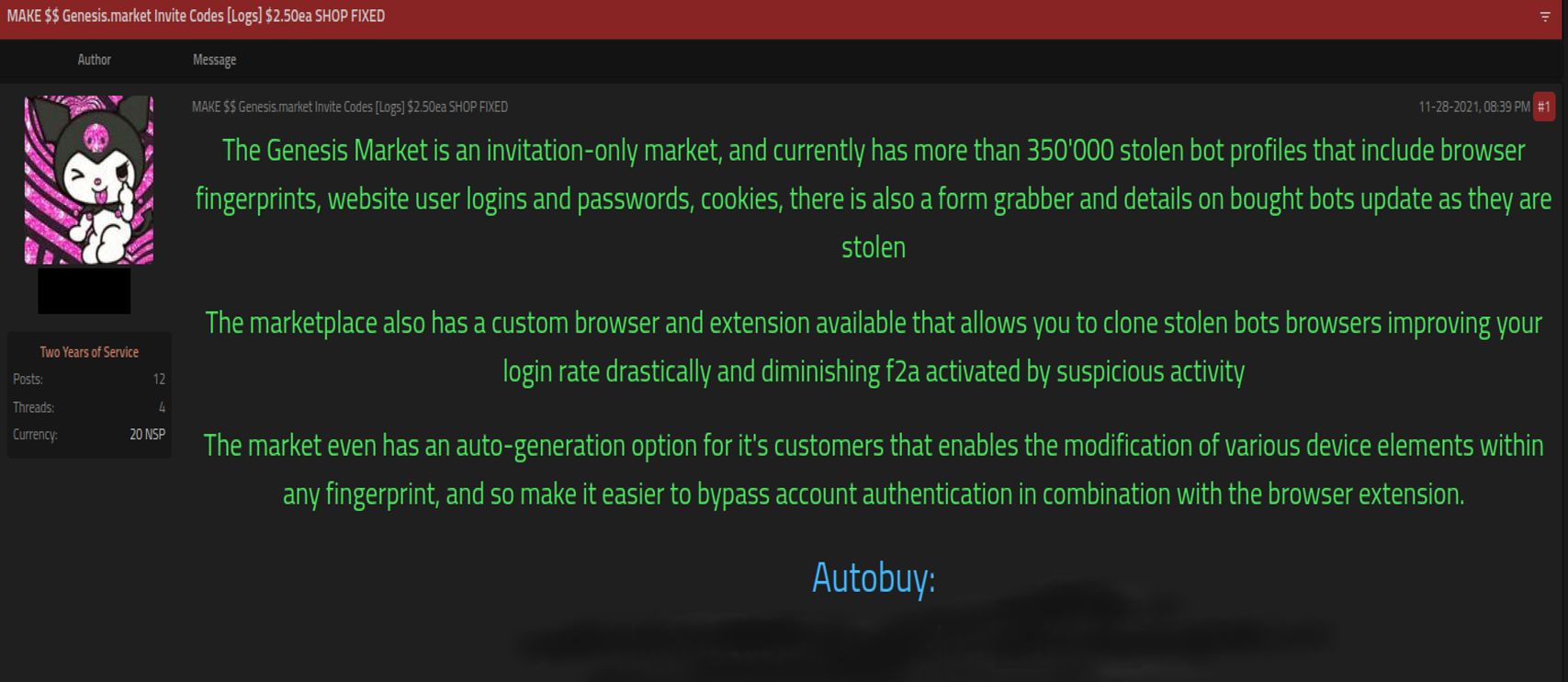

In any case, customer access to Genesis is invitation-only. Interestingly, this fact has spawned a robust secondary market for Genesis invitations. It’s also led to other criminal-activity sites pretending to be Genesis and, in effect, scamming would-be scammers seeking access to the marketplace.

Persistently Compromised Data

Unlike old-school combo lists and dumps of unrelated stolen credentials once shared in underground forums such as RaidForums and Breach Forums, IABs such as Genesis list individual bots with their corresponding cookies and other credentials. That lets threat actors see individual victims’ contexts, understand relationships between stolen data, and obtain more comprehensive information about the compromised system. And, as noted above, Genesis actively works to keep that information current. This in turn creates new areas for more innovative attacks. For instance, a darknet manual that we found during a recent investigation suggests to other criminals that they use complementary data (victim data beyond whatever’s required to access a specific account) from Genesis for kicking victims out of their accounts if stolen credentials are no longer valid:

Figure 1: Advice to would-be persistent attackers; Skrill is a provider of digital wallets, “fullz” is the full set of information on the victim (e.g., name and address), and the writer is talking about things attackers might do with Genesis data besides just attacking a victim’s wallet

In other words, even if victims realize their credentials are stolen and change their passwords to block the attackers, attackers can use complementary data to actively extort affected users. Meanwhile, as long as Genesis retains a foothold on the compromised machine, the credentials will eventually be re-stolen.

The more data Genesis has on a victim, the more the service charges for access to that bot: A victim represented by only a couple of user ID / password combos for social-media accounts can be had for under a dollar, while a victim whose information includes access for multiple bank accounts might go for hundreds of dollars. That allows the customer to buy precisely the information they need, perhaps even just one account’s worth. For instance, the single set of credentials that led to the June 2021 EA breach, which famously allowed the attackers into EA’s system through the gaming giant’s Slack, were purchased on Genesis for $10.

Bespoke Anti-Detection Tools

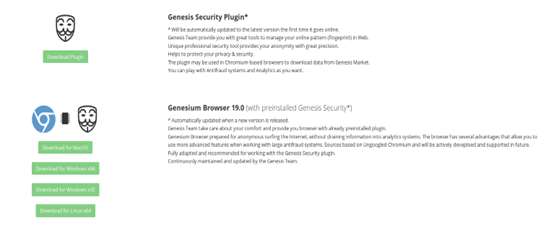

Once a would-be attacker has found a likely victim, Genesis facilitates the process of using the stolen information while, crucially, avoiding detection. The service offers two browser-based options for getting, editing, and using stolen information automatically: a Chrome extension and an “ungoogled” version of Chromium with a Genesis extension. The latter, called the “Genesium” browser, is advertised on the site as “continually maintained and upgraded by the Genesis team.”

Figure 2: Choose your well-maintained weapon

To be clear, detection avoidance – an important step for attackers once they’ve gained access – isn’t a subset solely of Genesis’ (or any other IAB’s) offering; there are a number of tools available online, just as there are more IABs in the world than Genesis. Anti-detection tools vary in how they shield the attacker’s browser from being identified; some are tuned to specific kinds of targets, such as social media. Genesis in this respect is worthy of note for being an integrated system; though more experienced attackers might mix and match tools and IABs to formulate their campaigns, the bar for successful attacks is uncomfortably low here.

Getting In

As mentioned, Genesis is an invite-only service, which has created demand by would-be bad guys for initial access to such a service. This demand creates a secondary marketplace providing matchmaker-like access for threat actors and invitation-only platforms such as Genesis, such as that shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3: Invite codes for Genesis for sale, allegedly

During our investigation, we occasionally found sites that claimed to be Genesis or Genesis-connected but were instead scam sites looking to separate would-be criminals from their credit-card information. One of these, which appears prominently in Google searches of “genesis market,” claims to offer free access to the marketplace but then requests a $100 deposit to “activate” the user’s account. Ultimately, signs point to the site not actually providing the would-be attacker with entry to the Genesis kingdom.

Slick Interface

We’ve noted that the data-correlation capabilities of Genesis are robust – comparable in their way to mainstream data-aggregation services. Likewise, the sites themselves are far from the old days of 133tsp34k and Matrix-wannabe interfaces. Genesis has a wiki and a page of Frequently Asked Questions; it has multilingual tech support; the text is well-written, and thought has gone into how to present the data in an appealing way. Return visitors are greeted with a dashboard describing which of their purchased bots (compromised systems) have been updated since their last visit. The data is easily searchable.

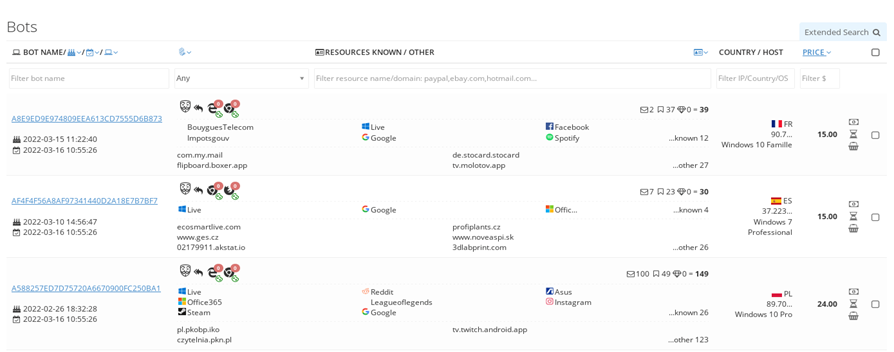

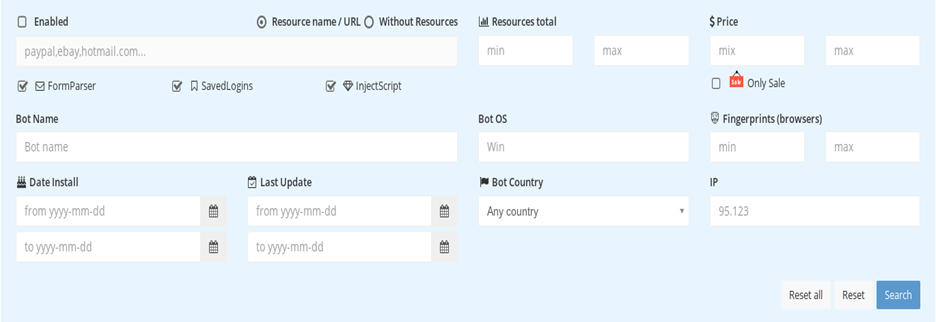

Two views of Genesis’ bot-search screens give a sense of its clean design:

Figure 4: The bot-search page where customers seek their bots. Among the types of information available are the hex “name” of each bot, information on the services and subscriptions it includes, the IP address and country of the bot, information on its operating system, and the current price

Figure 5: The Extended Search screen showing the URL of the targeted service, the IP address of the bot, country, operating system in use, and date parameters

Conclusion

Over the years, malicious-actor watering holes have come and gone, but overall being an Online Bad Guy took some skills, some digging, and some introductions to groups and resources that weren’t easy to find. Once those were found, actually getting access to and finding the treasure on a compromised system was hard, time-sensitive work – and the effort itself made nascent attacks easier for defenders to detect.

Those were happier times. Specialization in the online-crime sector brought us the IAB, specialists in gaining access and stealthily maintaining it for others – holding open the door, as it were, to other miscreants willing to pay. Professionalization brought us the polished likes of Genesis. The results, as we saw in this year’s Active Adversary report and continue to see as our Rapid Response and Managed Threat Response teams work with client after client, speak for themselves… in lingering tones.

For further reading

Kivilevich, Victoria and Raveed Laeb, “The Secret Life of an Initial Access Broker”

Ongoing IAB survey coverage from Digital Shadows: 2020 (recap and full report), 2021

Pernet, Cedric, “Initial access brokers: How are IABs related to the rise in ransomware attacks?”