Regular Naked Security readers will know we’re huge fans of Alan Turing OBE FRS.

He was chosen in 2019 to be the scientist featured on the next issue of the Bank of England’s biggest publicly available banknote, the bullseye, more properly Fifty Pounds Sterling.

(It’s called a bullseye because that’s the tiny, innermost circle on a dartboard, also known as double-25, that’s worth 2×25 = 50 points if you hit it.)

Turing beat out an impressive list of competitors, including STEM visionaries and pioneers such as Mary Anning (first to unravel the paleontological mysteries of what is now known as Dorset’s Jurassic Coast), Rosalind Franklin (who unlocked the structure of DNA before dying young and largely unrecognised), and the nineteenth-century computer hacking duo of Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage.

The Universal Computing Machine

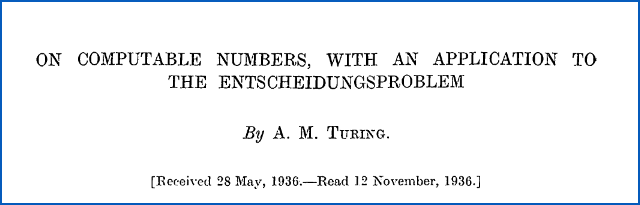

Turing was the groundbreaking computer scientist who first codified the concept of a “universal computing machine”, way back in 1936.

At that time, and indeed for many years afterwards, all computing devices then in existence could typically solve only one specific variant of one specific problem.

They would need rebuilding, not merely “reinstructing” or “reprogramming”, to take on other problems.

Turing showed, if you will pardon our sweeping simplification, that if you could build a computing device (what we now call a Turing machine) that could perform a certain specific but simple set of fundamental operations, then you could, in theory, program that device to do any sort of computation you wanted.

The device would remain the same; only the input to the device, which Turing called the “tape”, which started off with what we’d now call a “program” encoded onto it, would need to be changed.

So you could program the same device to be an adding machine, a subtracting machine, or a multiplying machine.

You could compute numerical sequences such as mathematical tables to any desired precision or length.

You could even, given enough time, enough space, enough tape and a suitably agreed system of encoding, produce all possible alphabetic sequences of any length…

…and therefore ultimately, like the proverbially infinite number of monkeys working at an infinite number of typewriters, reproduce the complete works of William Shakespeare.

As Turing himself wrote, in his seminal paper ON COMPUTABLE NUMBERS, WITH AN APPLICATION TO THE ENTSCHEIDUNGSPROBLEM:

It is possible to invent a single machine which can be used to compute any computable sequence.

The date of this, don’t forget, was 1936.

All modern electronic digital computers are nearly-but-not-quite Turing machines – our real-world computers have enormous, but not infinite, storage capacity, so there are some interesting problems they can still only compute in theory, not in practice.

Also, programming languages that are expressive enough to simulate a Turing machine, and therefore could be used to program a theoretical solution to any computational problem, are known as Turing complete.

The halting problem

Intriguingly, Turing showed in the same paper that even with a universal computing device, it’s not possible to write a program that can unerringly examine another program and predict its final behaviour.

Specifically – and this is where the Entscheidungsproblem, or “halting problem” comes in – you can’t tell in advance whether a program written for a Turing Machine will ever actually run to completion and therefore come up with the final answer you wanted.

You can write the code needed to give you an answer, but you can’t always be certain in advance that the answer will be computable – the algorithm might run for ever.

Clearly, you can prove by examination that some programs will terminate correctly, such as a loop that is coded to iterate exactly 10 times.

And you can show that some programs won’t terminate, for example if you were to write a loop to find three positive integers X, Y and Z for which X3 + Y3 = Z3. (Fermat’s Last Theorem tells us that no such solution exists.)

Indeed, if the halting problem were not a problem, and you could write a program to tell you if another program would terminate or not, you could use that “will-it-halt” program to solve a whole raft of mathematical conundrums.

Here’s an example, based on the fact that we strongly suspect that there are no odd perfect numbers.

A perfect number is equal to the sum of the numbers that divide exactly into it. Thus 6 is exactly divisible by 1, 2 and 3, and 6 = 1+2+3, so 6 is perfect. 12 is divisible by 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6, but 1+2+3+4+6 = 16, so 12 is not perfect. The numbers 1, 2, 4, 7 and 14 divide 28, and 28 = 1+2+4+7+14, the second perfect number. Then comes 496 and 8128, from which you might hope that the fifth perfect number would have five digits, then six, and so on. But they thin out really quickly, with the tenth perfect number already being 54 digits long. The 50th perfect number (that we know of, anyway) runs to nearly 50 million digits. All perfect numbers found so are are even, i.e. can be divided by 2.

It’s trivial to write a program to test all the odd numbers, one by one, until you find an odd perfect number, then to print it out and terminate, which would prove that not all perfects are even:

function findoddone()

local n = 3

while true do

if isperfect(n) then

print('found one:',n)

os.exit()

end

n = n + 2

end

end

But as long as the program keeps running you will never be sure whether all perfects are even, or whether you just haven’t waited long enough yet to prove there’s an odd one out there.

However, if there existed a program that could analyse your perfect number calculator and reliably predict if it would terminate or not, then you could prove whether any odd perfect numbers existed simply by running your will-it-halt detector:

if willithalt(findoddone) then

print('proved - at least one odd perfect exists')

else

print('disproved - all perfects are even')

end

You wouldn’t find out the actual value of any odd perfect numbers, if indeed they exist, because you wouldn’t actually be running your perfect number testing function.

You’d simply be running your will-it-halt program to determine the outcome of the detector, and that on its own would complete your proof: you would know whether all perfects were even or not.

But you can’t rely on completing the proof that way, because of the halting problem, and Turing proved this before computers as we know them even existed.

Implications for cybersecurity

You can extend the halting problem result in important ways for cybersecurity, as we wrote on what would have been Turing’s 100th birthday in 2012:

[The halting problem means, for example,] that you can’t write an anti-virus program which never needs updating. All those criticisms about the imperfection of anti-virus are true!

But the halting problem applies to everyone. Not just to anti-virus, but to code analysers, behaviour blockers, [machine learning systems, intrusion monitors], network flow correlators, [exploit detectors] and so forth. No security solution can be perfect, because no solution can decide all the answers. That’s why defence in depth is really important, and why you should run a mile from any security vendor who still makes claims like “never needs updating.”

By the way, Turing’s result can be turned around to make it a bit more optimistic: you can’t write [malware] that will be undetectable by all possible [anti-malware] programs. So the good guys always win in the end.

Multifactor science superhero

As you may already know, Alan Turing distinguished himself in many other ways beyond his pioneering work on Turing machines:

- He was a massively important part of the British codebreaking team at Bletchley Park in England during World War II.

- He was a major figure in the design and construction of one of Britain’s first digital electronic computers, the Pilot ACE.

- He came up with what we now call the Turing Test in an early investigation into how to measure artifical intelligence, in particular how we might answer the question “Can machines think?”

- He conducted groundbreaking mathematical work on how patterns form in nature, such as a leopard’s spots or a zebra’s stripes.

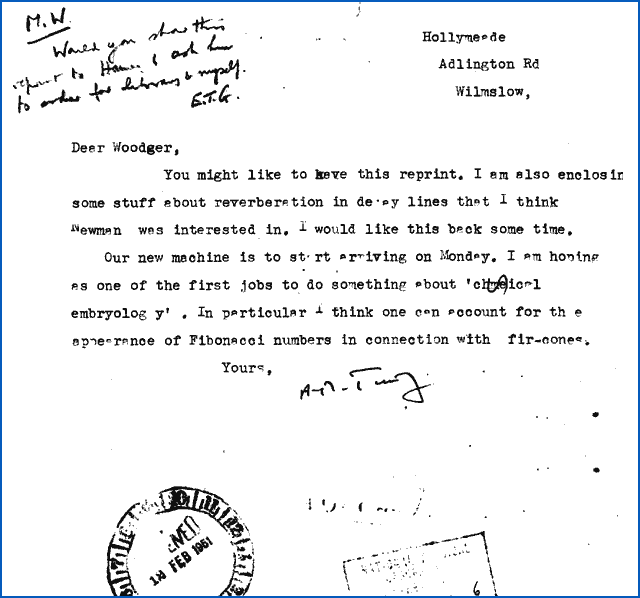

A fascinating insight into Turing’s interest in the field of morphogenesis – how living structures develop – can be gleaned from an archived letter he wrote to one of the Pilot ACE team shortly before the first computer was delivered:

Dear Woodger,

[. . .] Our new machine is to start arriving on Monday. I am hoping as one of the first jobs to do something about ‘chemical embryology’. In particular I think one can account for the appearance of Fibonacci numbers in connection with fir-cones.

Yours, A.M. Turing

[Received 12 Feb 1951]

A life tragically cut short

Sadly, little more than three years later, Turing was dead.

Turing was gay in an era when that was proscribed by law in Britain.

This ultimately led to his prosecution and conviction in court, where he was sentenced to undergo the administration of a carcinogenic hormone, apparently as an alternative to prison.

Turing was also formally ostracised by the Establishment – who had, of course, conveniently ignored the law when his wartime contribution was so desperately needed – and, in the ultimate tragedy, killed himself in 1954.

The banknote unveiled

It’s now official: the Bank of England has just unveiled the Alan Turing £50 originally announced in 2019.

The “Turing bullseye” banknote will enter circulation in three months’ time.

As we said in 2019:

[T]he £50 is the biggest English banknote in circulation, in both size and value, so perhaps it is a fitting tribute for Turing after all – one that will remind us of the huge value of mathematicians and scientists who can blend theory and practice in ways that advance the world as a whole.

As the Bank of England’s website proclaims, “Think science and celebrate Alan Turing.”

Details we like:

- RED: Picture of Pilot ACE computer in the background.

- ORANGE: Table from the On Computable Numbers paper.

- YELLOW: Wheel design from the British Bombe, a mechanical codebreaking computer of Turing’s design from wartime days.

- GREEN: His prescient words about how dramatically digital computers would change the world.

- BLUE: His birthday (19120623) encoded in binary on tape.

- VIOLET: Sunflower anti-counterfeiting icon with initials AT, symbolising Turing’s work on morphogenesis.

David Pottage

I think that in practice a computer program to find counter examples to Fermat’s last theorem would halt due to limited arithmetic precision.

Most won’t be fooled by 10**3 + 9**3 = 12**3 but unless your compiler has support for integers bigger than 128 bits, you might be fooled by 3987**12 + 4365**12 = 4472**12

Paul Ducklin

As I said above, our real-world computers aren’t strictly Turing Machines because of they do not have infinite storage and therefore must ultimately make approximations…

Of course, 128 bits is small for modern “computer integers” – cryptographic arithmetic using thousands of bits of precision is commonplace these days, though admittedly you can’t use any of the standard C integer types for that.

With OpenSSL’s bignum library (here used from Lua):

> bn = require ‘openssl.bignum’

> s = bn.new(3987)^12 + bn.new(4365)^12

> v = bn.new(4472)^12

> s

63976656349698612616236230953154487896987106

> v

63976656348486725806862358322168575784124416

> s == v

false

> s-v

1211886809373872630985912112862690

>

With Python’s built-in long integers:

>>> s = 3987**12 + 4365**12

>>> v = 4472**12

>>> s

63976656349698612616236230953154487896987106L

>>> v

63976656348486725806862358322168575784124416L

>>> s==v

False

>>> v

63976656348486725806862358322168575784124416L

>>> s==v

False

>>>

>>> s-v

1211886809373872630985912112862690L

Paul Ducklin

Ah, I may have been semitrolled!?! Seems that 3987**12 + 4365**12 = 4472**12 has history (thanks, Wolfram.com!) on The Simpsons and was presumably chosen because a naive attempt to check the calculation read off a video freeze-frame using a regular C program would “succeed” for 16-bit, 32-bit, 64-bit and 128-bit integers, and a quick cross-check of the last digit of each side of the “equality” would give a tiny bit of extra “evidence” because they both end in -6.

Nicely done, Sir! I did wonder what had made you choose those values and now wish I had checked sooner :-)

David Pottage

Most handheld scientific calculators, and many weakly typed programming languages will silently switch to floating point math when integer math overflows. Python 3 is unusual among scripting languages in that it switches to bigint math instead.

If you try to test the conjecture using the windows calculator app (which appears to use 64 bit floats internally) then the 12th root of 3987**12 + 4365**12 is an integer to 7 decimal places. If you did not know better you could easily convince yourself that the fractional part is due to a floating point loss of precision.

I also tested the calculation on my son’s Casio fx-83GT hand held scientific calculator (as recommended by all local secondary schools for GCSE maths) and it reported that the 12th root of 3987**12 + 4365**12 is *EXACTLY* 4472

As for the link to The Simpsons, I knew that there was a false fermat’s last theorem counterexample in the show, but I did not pick the one I did because it was in the show, I just googled for “fermat’s last theorem false counterexample” and picked the largest.

Paul Ducklin

I used my trusty HP42 simulator, Free42 (cool free software for Windows, Mac, Linux, Android, iOS, see: https://thomasokken.com/free42/) in Decimal mode, which gives you more faithful answers for decimal inputs that a binary-based calculator. Where p = power (HP y^x key) and r = reciprocal (HP 1/x key), I get:

3987 12 p 4365 12 p + 12 r p

4472.00000001

Using MAPM on Linux (Mike Ring’s Arbitrary Precision Math Library, from: https://github.com/LuaDist/mapm), which has a command line app that works like a HP RPN calculator, I got:

$ mapmcalc 3987 12 p 4365 12 p + 12 r p

4472.000000007059290738213529241

So it is indeed pretty close to an integer :-)

Given that 4472.00000001 has 12 significant digits and given that 64-bit floats offer about 16 decimal digits of precision, then regular C ‘double’ variables should spot the difference, too:

—cut here—

#include

#include

int main(void) {

double x = pow(3987,12);

double y = pow(4365,12);

printf(“%24.17f”,pow(x+y,1/12.0));

return 0;

}

—cut here

Produces 4472.00000000705767889, which differs from the MAPM megaprecision answer at the 16th significant digit.

Bacchanalia

…er…Mary Anning, not Denning, and SHOCK – she had not been to university (and despite the current film, there is absolutely nothing to indicate she might have been gay)

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks! I have no idea how that error happened – I listed all 12 of the shortlisted possibilities in my last article on this topic, and “copied” (by memory, not via Crtl-C) the names from there, where there was no mistake. I knew there was a movie made about her recently but I have been doubly determined not to watch it after accidentally watching a 2001 movie called “Enigma” (I was on a long-haul plane flight; that’s my excuse). If I want to enjoy a dramatisation of a significant scientist’s life, why would I want to watch someone else’s version of it?

I probably ought to have repeated the shortlist in this article, but didn’t to save space…

…however, I am going to do so here. The 12 shortlisted entries for “STEMmers on the new £50” (two entries were double-acts) were:

* Mary Anning (1799-1847) – a self-taught palaeontologist known around the world for the fossil discoveries she made in her hometown of Lyme Regis.

* Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac (1902-1984) – whose research revolutionised our understanding of the universe’s smallest matter.

* Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958) – who drove the discovery of DNA’s structure, a critical breakthrough in our understanding of the biology of life.

* Stephen Hawking (1942-2018) – who made outstanding contributions to our understanding of gravity, space and time.

* William (1738-1822) and Caroline Herschel (1750-1848) – a brother and sister astronomy team devoted to uncovering the secrets of the universe.

* Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1910-1994) – whose research using x-ray crystallography delivered ground-breaking discoveries which shaped modern science and helped save lives.

* Ada Lovelace (1815-1852) and Charles Babbage (1791-1871) – visionaries who imagined the computer age.

* James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879) – who made discoveries which laid the foundations for technological innovations which have transformed our way of life.

* Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920) – whose incredible talent for numbers helped transform modern mathematics.

* Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) – who uncovered the properties of radiation, revealed the secrets of the atom and laid the foundations for nuclear physics.

* Frederick Sanger (1918-2013) – whose pioneering research laid the foundations for our understanding of genetics.

* Alan Turing (1912-1954) – whose work on early computers, code-breaking achievements and visionary ideas about machine intelligence made him one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century.

(Source: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/banknotes/50-pound-note-nominations)

Larry Marks

Correction:

> 5. BLUE: His birthday (19120623) encoded in binary.

should be:

5. BLUE: His birthday (19120623) encoded in binary ON TAPE!

Paul Ducklin

Good point! I added that extra detail into the article itself, thanks :-)

Richard Pennington

The specific case of X^3 + Y^3 = Z^3 is the p=3 case of Fermat’s Last Theorem, and (for this specific case) proofs have been known since long before Andrew Wiles. The following paragraph is from Wikipedia …

In 1770, Leonhard Euler gave a proof of p = 3, but his proof by infinite descent contained a major gap. However, since Euler himself had proved the lemma necessary to complete the proof in other work, he is generally credited with the first proof. Independent proofs were published by Kausler (1802), Legendre (1823, 1830), Calzolari (1855), Gabriel Lamé (1865), Peter Guthrie Tait (1872), Günther (1878), Gambioli (1901), Krey (1909), Rychlík (1910), Stockhaus (1910), Carmichael (1915), Johannes van der Corput (1915), Axel Thue (1917), and Duarte (1944).

The achievement by Andrew Wiles (1995) was to prove the non-existence of solutions of X^p + Y^p = Z^p for *any* power p > 2.

Paul Ducklin

Yes, I realised that, because I had locked p (in your notation) at 3, I was rather underplaying (or was I overplaying?) Sir Andrew Wiles’s general proof… buy having added the link I was somehow disinclined to remove it, as I rather liked having it there, which is admittedly a rather weak reason!

Technically my observation is perfectly accurate (given that if we have known since the late 1700s then we have known since 1995)… but I do think I should reword it.

(I have now edited it just to say, “Fermat’s Last Theorem says, ‘No.'”)