Of all classes of cybersecurity threat, ransomware is the one that people keep talking about. It can bring businesses to a halt and the ransom demands often range from hundreds of thousands to tens of millions of dollars.

These two factors alone mean that being hit by ransomware is a big deal, especially since most ransomware adversaries have now incorporated data theft into their attacks, giving targets an even bigger headache as they see their intellectual property leaked on the web.

For defenders, stopping these attacks is of paramount importance. Figuring out how the adversary was able to compromise the business in the first place is equally critical.

Since every organization has its own password policy, network topology and security configuration, ransomware attacks nowadays are often controlled by humans to ensure success. They leverage privileged accounts – often stolen – to execute commands as if they were physically at a keyboard in the office.

Before this can happen, however, adversaries deliver a flexible post-exploitation agent like Cobalt Strike or Meterpreter (a remote access agent or trojan). This agent facilitates most active adversary tactics, including execution, credential access, privilege escalation, discovery, lateral movement, collection, exfiltration, and impact (as charted in the MITRE ATT&CK matrix).

Many security products have a hard time reliably detecting these remote access agents, as they are highly configurable and deliberately packed, obfuscated or encrypted to evade network and endpoint defenses.

This is evidenced by the many high-impact incidents where such agents are used, including high-profile ransomware and nation-state attacks. For example, similar remote access agents were used in massive supply-chain attacks against targets such as SolarWinds, CCleaner, NetSarang (“ShadowPad”), and ASUS (“ShadowHammer”).

The Stager

Initial access can occur in a variety of ways, from stolen credentials used to exploit a public-facing VPN or exposed RDP server, to the unintentional execution of malicious macros embedded in an Office document.

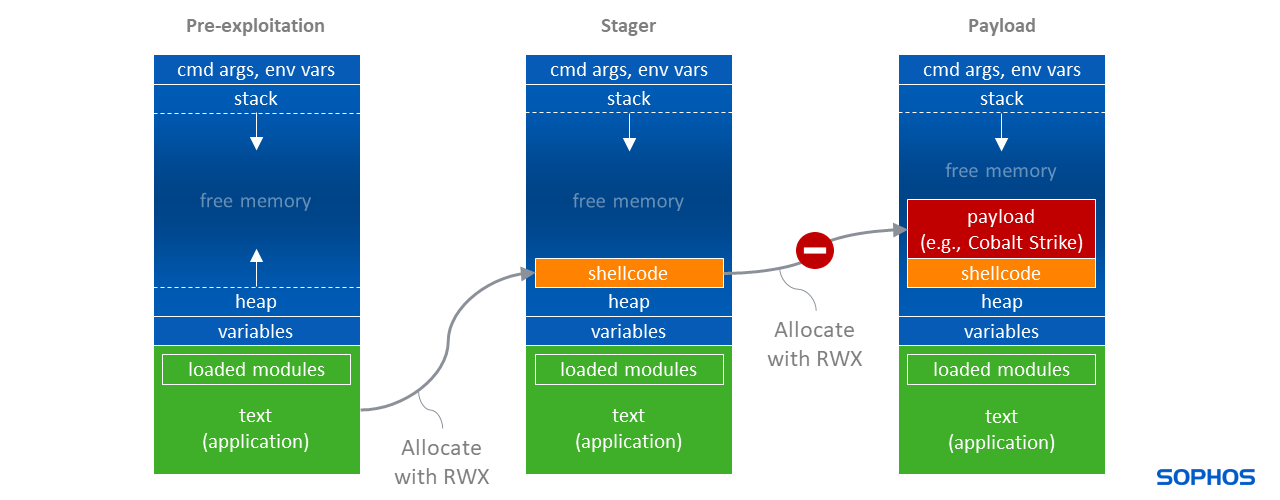

After initial access, the delivery of a remote access agent typically happens in stages. The first stage of an attack is often meant to determine if a valuable target has been reached and which agent to deliver depending on operating system architecture. This early malicious code – known as a “stager” or “loader” – is typically a handler or conduit that delivers the payload straight into memory, often evading deficient antivirus and machine learning examinations.

A stager typically contains little code so that it cannot be determined if it is there for a malicious purpose – it could also be benign.

Once the stager delivers the remote access trojan, that agent then delivers and executes additional payloads (like Mimikatz) straight into memory, preferably into or from a trusted Windows process or line-of-business application.

Think of it as a reusable multi-stage-to-orbit rocket, whereby the space rocket itself is not malicious in nature but the ultimate payload may be intended for malicious use.

Defense Evasion

Despite advances in endpoint protection with cloud-delivered analysis, behavioral analysis and machine learning, adversaries are still able to evade detection by obfuscating or polymorphically rearranging their malicious code.

Prevalent trojans like Emotet, Trickbot and Qakbot are frequently re-obfuscated and packed to evade detection by network and antivirus defenses.

So, although defense evasion is not a new tactic, it results in attacks that deliberately distort detections intended to identify known threat families, as well as feature-based machine learning. It does this by using code structures and sequences that even well-trained models fail to predict.

The ultimate code is unknown and is often “allowed” (to prevent false positives), while the threat’s behavior – its purpose – remains the same. Shellter and Phantom Evasion are two tools that obfuscate well-known malicious code for defense evasion.

Fortunately, when a malware is loaded into memory it is unpacked or de-obfuscated. Once it is no longer cloaked by packing/obfuscation it becomes easier to detect. Unfortunately, even though endpoint defenses have the capability to scan memory, this is not often done due to the impact on performance.

Also, machine-learning models are typically not tailored towards memory scanning. This makes a memory scan dependent on the detection of sequences of known-bad code sequences (a “signature”). Code sequences can also be rearranged without any effect on function to evade detection. Skilled threat researchers can select a good code sequence that covers a range of obfuscated malware variants, but attackers will adapt.

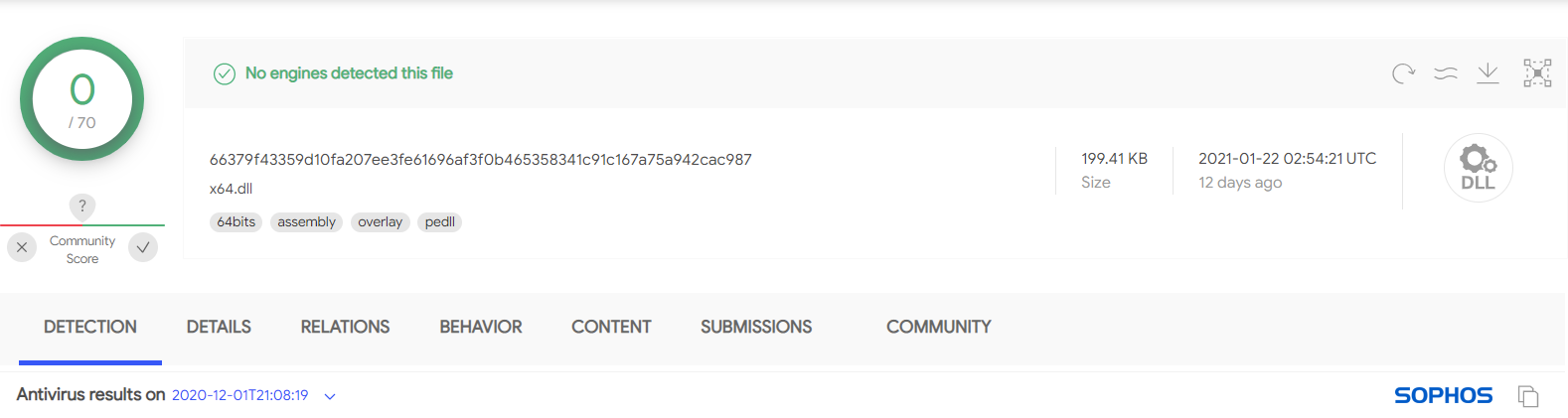

Below (figure 1) is a stager detected by Sophos Intercept X in a recent Conti ransomware attack:

SHA-256: 66379f43359d10fa207ee3fe61696af3f0b465358341c91c167a75a942cac987

Loaded as: rundll32 C:\ProgramData\x64.dll entryPoint

This offensive tactic has fueled a security industry trend to “record everything” with Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR). Using EDR, human threat responders (be it an in-house security operations team or an external service like Sophos’ 24/7 Managed Threat Response) can sift through the recordings and help detect such threats early, ideally before any ransomware is deployed. These services are also helpful in investigating a breach or incident.

Cobalt Strike Beacon

A remote access agent that we frequently see delivered in protected networks is Cobalt Strike Beacon. Although originally intended for security assessments, the Cobalt Strike toolset has been leaked to cybercriminals. It is also used by nation-state attackers to keep costs low and frustrate attribution.

An example is the recently reported SolarWinds supply-chain incident (or “Solorigate”), where a Cobalt Strike Beacon deployed by attackers remained undetected for many months.

Cobalt Strike is also a popular go-to toolset for many human-operated ransomware attacks, including Conti – a ransomware family recently reported on in depth by Sophos researchers – thanks to its typical properties.

These include Cobalt Strike’s malleable command-and-control (C2) profile, configurable process injection and obfuscate-and-sleep features. This last feature is exactly what it sounds like: it obfuscates itself in memory while it waits for a command. When the agent wakes up it restores itself to its original state. This makes it difficult to spot in memory.

Modern Operating System Memory Permissions

Fortunately, we have identified a static characteristic that is common across all these remote access agents. But before diving into this, it may help to explain memory permissions.

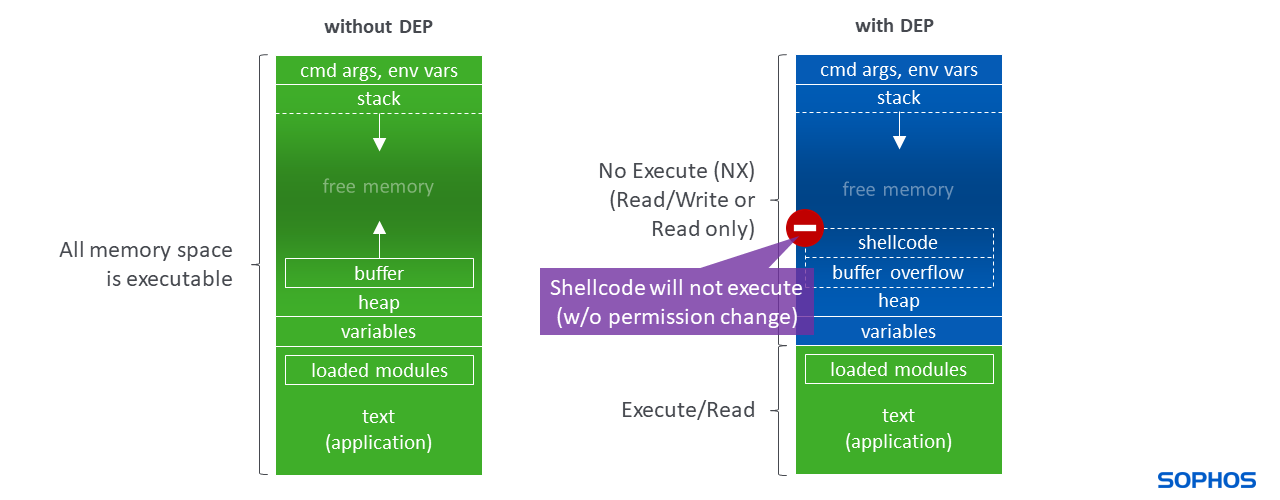

Since 2003, with AMD’s Athlon 64 and Intel’s Pentium 4 processors, central processing units (CPUs) in mainstream computers contain a technology called NX bit (No-eXecute), that segregates regions of memory for either the storage of processor instructions (code), or the storage of data. With the Windows XP Service Pack 2 (SP2) in 2004, support for the NX technology – to segregate code and data – was introduced in Windows and is known as Data Execution Prevention (DEP).

For example, a memory region that contains an image shown in the web browser does not have code execution permissions, whereas the region that contains the core application – the web browser itself – can execute code.

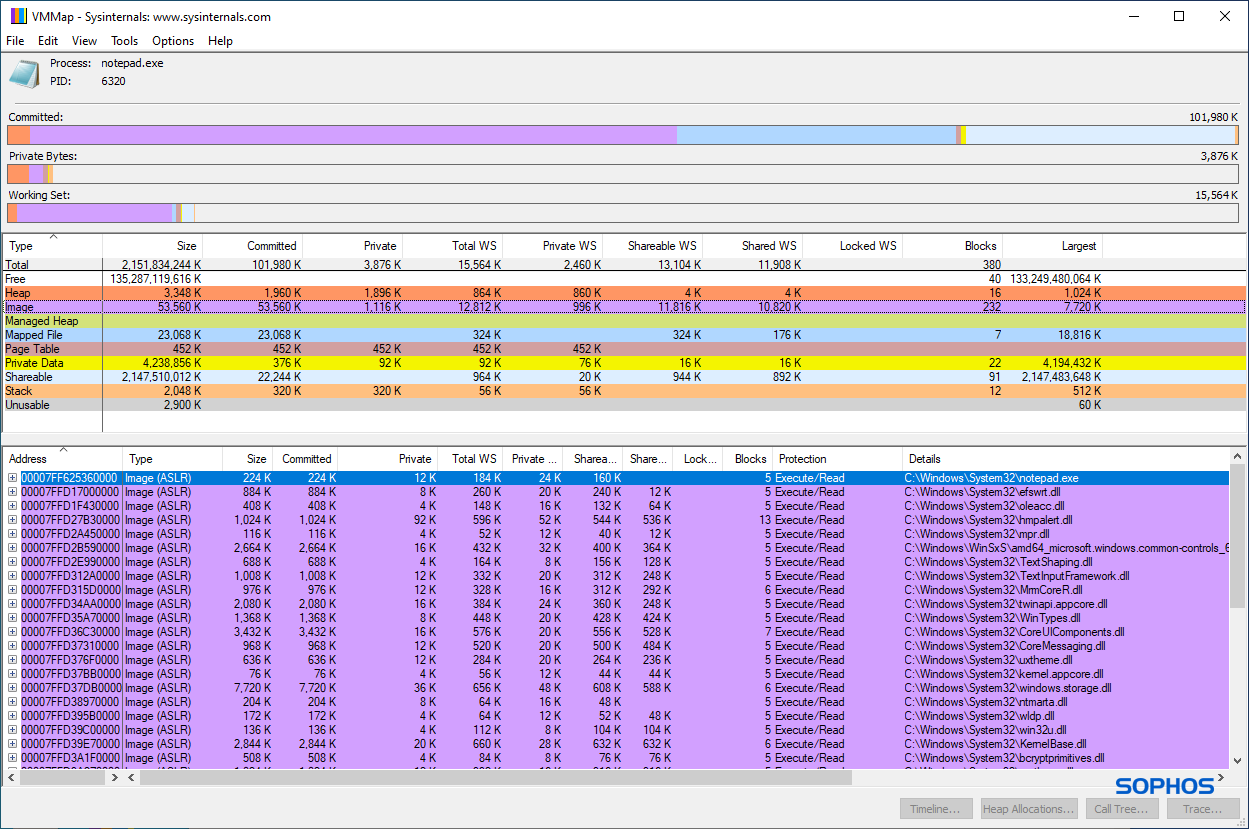

Typically, the application itself, as well as its dynamic link libraries (DLLs), are loaded into a memory region called Image.

Applications need in-memory workspace to operate. This memory is dynamically allocated (and freed) to e.g., temporarily store or cache data like web pages with text, images, and scripts, so this data can be processed and displayed. For simplicity, we generally call this workspace the Heap, and it is largely represented as “Private Data.” The Heap grows (and shrinks) during the lifetime of the applications’ “process.”

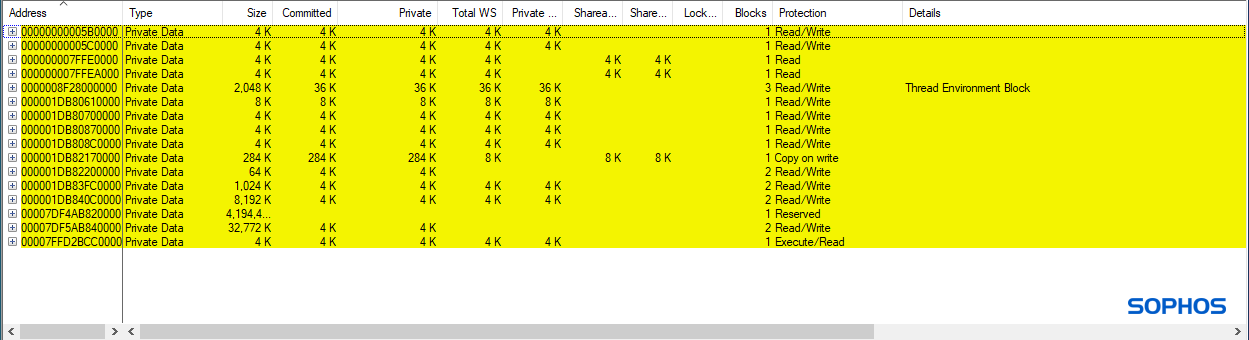

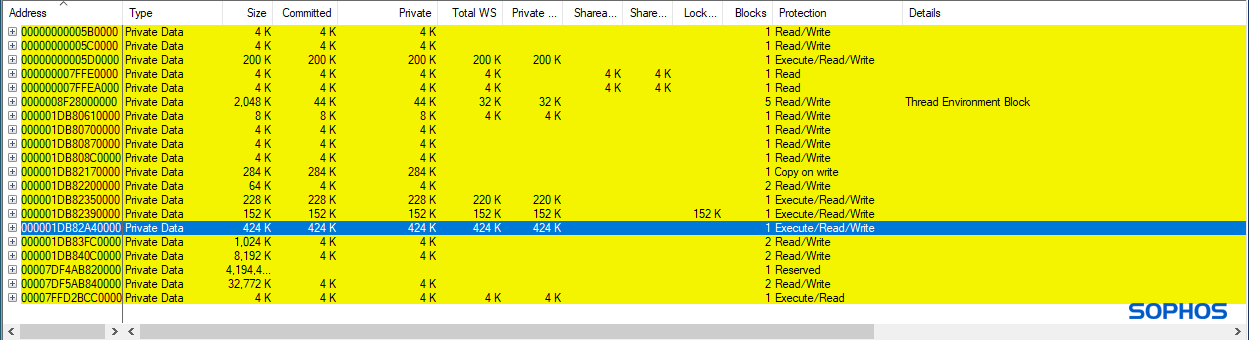

Image memory is normally protected with Execute/Read permissions. Heap memory with only data in it is typically allocated Read/Write permissions. When a Heap memory region is populated with code, permissions are set to Execute/Read/Write or Execute/Read.

Figures 2 through 4 below illustrate the memory layouts of NOTEPAD.EXE before and after compromise.

Data Execution Prevention (DEP), or executable-space protection, is a system-level memory protection that ensures data-only regions cannot execute code. The purpose of DEP is to prevent arbitrary code execution when a buffer overflow is exploited, i.e., to prevent excess data (arbitrary code) past a buffer boundary from executing in a data-only memory region.

Because of DEP, every running application (“process”) that requires more memory, for instance to unpack code, must allocate or mark this additional memory region with code execution permissions before it can hand over code execution to this region. If this memory region does not have at least Execute/Read permissions, an exception is raised by the processor hardware and the process is terminated by the operating system.

This ordinary memory allocation is a fundamental and essential behavior that can also be observed in many covert attacks. Interestingly, especially in an attack scenario, the stager is typically (due to code injection or unpacking) running from Heap memory. And this stager allocates additional executable memory on the Heap for the ultimate agent. This ‘heap-heap’ memory allocation behavior is a mainstay of the threat’s covert properties and abilities.

Paradigm Shift

In a multi-year project called “HeapHeapHooray”, Sophos designed a new practical protection that blocks this malicious memory allocation behavior, while being highly compatible with existing applications.

The end result is a system-level mitigation, called “Dynamic Shellcode Protection,” with a code-agnostic design and the ability to intercept many cyberattacks involving remote access trojans, fileless malware and ransomware.

In recent attacks, our early-access customers have seen first-hand the effectiveness of this protection. When a process violates the memory allocation barrier imposed by the Dynamic Shellcode Protection, the mitigation generates an alert with a run-length encoded base64 memory dump from the memory region where the allocation call originated from. This data can provide threat responders with insight into the breach and help them to quickly trace the initial access and where the attack is operated from (its command-and-control server).

MitigationL DynamicShellcode

Timestamp: 2021-01-15T05:50:38

Platform: 10.0.14393/x64 v321 06_3f*

PID: 2856

Application: C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe

Created: 2016-07-16T13:19:06

Modified: 2016-07-16T13:19:06

Description: Windows host process (Rundll32) 10

Shellcode: (HHA) (0x00400000 bytes)

Owner of CALLER: (anonymous; doc.dll)

OwnerModule

Name: doc.dll

Thumbprint: 9be4c0089b841d45871f054cb797f099f2a89d71d6158110f1e3a78cb9a9e3ae

SHA-256: 2cd05616874445c655eaf723c549f35cc6c379b1877750788adf2c5d6b86cd09

SHA-1: c7bcb3b84244a22e6ee9699cfbd86dc9f27fc677

MD5: c5e8007b5fa2e25625d659fa5c6604ff

| 0000024F0AEE034B ffd5 | CALL | RBP |

| 0000024F0AEE034D 4893 | XCHG | RBX, RAX |

| 0000024F0AEE034F 53 | PUSH | RBX |

| 0000024F0AEE0350 53 | PUSH | RBX |

| 0000024F0AEE0351 4889e7 | MOV | RDI, RSP |

| 0000024F0AEE0354 4889f1 | MOV | RCX, RSI |

| 0000024F0AEE0357 4889da | MOV | RDX, RBX |

| 0000024F0AEE035A 41b800200000 | MOV | R8D, 0x2000 |

| 0000024F0AEE0360 4989f9 | MOV | R9, RDI |

| 0000024F0AEE0363 41ba129689e2 | MOV | R10D, 0xe2899612 |

| 0000024F0AEE0369 ffd5 | CALL | RBP |

| 0000024F0AEE036B 4883c420 | ADD | RSP, 0x20 |

| 0000024F0AEE036F 85c0 | TEST | EAX, EAX |

| 0000024F0AEE0371 74b6 | JZ | 0x24f0aee0329 |

| 0000024F0AEE0373 668b07 | MOV | AX, [RDI] |

| 0000024F0AEE0376 4801c3 | ADD | RBX, RAX |

—– SNIP HERE —–

—– END SNIP —–

Loaded Modules

—————————————————————————–

00007FF8D34A0000-00007FF8D35D2000 hmpalert.dll (SurfRight B.V.),

version: 3.7.17.317

0000000065180000-00000000651BA000 doc.dll (),

version:

00007FF8C9AA0000-00007FF8C9ADE000 SOPHOS~1.DLL (Sophos Limited),

version: 10.8.9.610

Process Trace

1 C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe [2856]

rundll32.exe C:\Programdata\doc.dll entryPoint

2 C:\Windows\System32\wbem\WmiPrvSE.exe [4636]

C:\Windows\system32\wbem\wmiprvse.exe -secured -Embedding

3 C:\Windows\System32\svchost.exe [748]

C:\Windows\system32\svchost.exe -k DcomLaunch

4 C:\Windows\System32\services.exe [656]

5 C:\Windows\System32\wininit.exe [552]

wininit.exe

6 C:\Windows\System32\smss.exe [452]

\SystemRoot\System32\smss.exe 000000d4 0000007c

7 C:\Windows\System32\smss.exe [360]

\SystemRoot\System32\smss.exe

Thumbprint

7eba537e2dd90dded5c4950f939fbe9a9678b33f840382136d317550ea65a926

Module based thumbprint

9be4c0089b841d45871f054cb797f099f2a89d71d6158110f1e3a78cb9a9e3ae

Decoding the run-length and base64 encoded memory dump results in the following human-readable strings:

/Menus.aspx

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Referer: https://locations[.]smashburger.com/us/ky/louisville/312-s-fourth-st.html

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko)

docns.com

Dynamic Shellcode Protection

In January 2021, we started enabling this protection across our customer base running Sophos Intercept X. The novel protection is signature-agnostic, meaning it does not make assumptions on the memory allocation, i.e., whether it is for a benign or malicious purpose – while being highly compatible with existing applications.

The protection is not meant as a silver bullet for all attacks but is expected to make a significant impact on the threat landscape. Just as not all machine learning systems are equal, not all memory protections are equal, either. We believe our unique Dynamic Shellcode Protection will have a considerable impact as adversaries now face a defense that blocks a fundamental behavior of their covert remote access agents.

The Dynamic Shellcode Protection does not rely on the cloud or machine learning and as such is a paradigm shift in the battle against many obfuscated malware and memory-delivered post-exploitation agents, including Cobalt Strike Beacon.

Note: In attacks with Cobalt Strike Beacon, more of its fileless in-memory techniques can be observed. For example, the Sophos APCViolation protection blocks Beacon’s code injection when it attempts to run a capability in the address space of another process via an asynchronous procedure call (APC) – MITRE ATT&CK T1055.004. APC injection is regularly used because many endpoint protection products have no visibility into this event. Dynamic Shellcode Protection aims to undermine the fundamental behaviors of remote access agents that make hand-on-keyboard attacks possible from remote.

Mitigation Robustness

The Sophos Threat Mitigation team (the team behind HitmanPro and HitmanPro.Alert) has introduced many other novel mitigations against attack techniques observed in the field.

Incorporated into Sophos Intercept X, these mitigations are designed to prevent and limit the effects of arbitrary code execution. They do this by monitoring for undesired behaviors, i.e., commands executed by the kernel via functions that are fundamentally required to manipulate data on disk or memory – in both unknown and trusted applications. These mitigations are uniquely robust. They survive obfuscations by being signature-agnostic, which means they do not rely on brittle machine code inspection to detect attacks. Also, these technologies do not rely on the cloud or machine learning.

The following table is a list of all current Sophos proprietary mitigations that Sophos Intercept X adds to Windows 10. Contrary to Windows 10 Exploit Guard, the mitigations offered by Sophos are different, highly compatible, default enabled, and do not require configuration.

| Description | Module | Level | Equivalent in Windows 10 |

| Enforce Data Execution Prevention (DEP) | DEP | Application | Yes |

| Mandatory ASLR on modules | DEP (ASLR) | Application | Yes |

| Bottom-up ASLR | DEP (ASLR) | Application | Yes |

| Validate exception chains | SEHOP | Application | Yes |

| Validate API invocation | ROP | Application | Optional |

| Prevent API invocation from stack memory | CallerCheck | Application | – |

| Prevent process creation from dynamic memory | CallerCheck | Application | – |

| Import address filtering (IAF) | IAF | Application | Optional |

| Validate stack integrity | StackPivot | Application | Optional |

| Validate stack memory protection | StackExec | Application | Optional |

| Validate heap content integrity | HeapSpray | Application | – |

| Block memory addresses commonly abused for heap spraying | HeapSpray | Application | – |

| Block remote images | LoadLib | Application | Optional |

| Prevent code injection via reflective DLL | LoadLib | Application | Optional |

| Prevent vtable hijacking in Flash Player | VTableHijack | Application | – |

| Enforce sandbox around VBScript in Internet Explorer | Lockdown | Application | – |

| Prevent DLL hijacking on web downloads | DllHijack | Application | – |

| Prevent application from executing of newly created executable content | Lockdown | Application | – |

| Prevent application from using living-of-the-land binaries | Lockdown | Application | – |

| Prevent application from creating autorun registry entry | Lockdown | Application | – |

| Prevent Win32 API calls from Office macro | Lockdown | Application | Optional |

| Prevent inspection bypass via unsupervised system calls | SysCall | Application | – |

| Prevent inspection bypass via WoW64 marshalling layer | SysCall | Application | – |

| Prevent inspection bypass via Heaven’s Gate | SysCall | Application | – |

| Validate web browser integrity | Intruder | Application | – |

| Ransomware protection with data rollback, folder-agnostic | CryptoGuard | System | – |

| Block ransomware that abuses Windows EFS | CryptoGuard | System | – |

| Boot and volume record overwrite protection | WipeGuard | System | – |

| Prevent intersectional control flow | CodeCave | System | – |

| Prevent code execution from residual memory beyond the image size | CodeCave | System | – |

| Prevent overwriting of the entry-point from dynamic memory | CodeCave | System | – |

| Prevent privilege escalation via token theft | PrivGuard | System | – |

| Prevent privilege escalation via secondary logon handler | PrivGuard | System | – |

| Prevent credential theft via LSASS | CredGuard | System | Optional |

| Prevent APC violation | APCViolation | System | – |

| Prevent abuse of atom tables via APC | APCViolation | System | – |

| Stop module load order disrespect via deception | Kernel32Trap | System | – |

| Prevent process hollowing | HollowProcess | System | – |

| Prevent process environment block manipulation | HollowProcess | System | – |

| Prevent main thread hijacking | HollowProcess | System | – |

| Validate CTF protocol caller | CTFGuard | System | – |

| Prevent dynamic shellcode | DynamicShellcode | System | – |

| Prevent dynamic shellcode from other processes | DynamicShellcode | System | – |

| Prevent in-memory manipulation of AMSI.DLL | AmsiGuard | System |

– |