Two weeks ago was Cybersecurity Awareness Month’s “Fight the Phish” week, a theme that the #Cybermonth organisers chose because this age-old cybercrime is still a huge problem.

Even though lots of us receive many phishing scams that are obvious when we look at them ourselves…

…it’s easy to forget that the “obviousness” of many scam emails comes from the fact that the crooks never intended those scams for us in the first place.

The crooks simply sent them to everyone as a crude way of sending them to someone.

So most scams might be obvious to most people, but some scams are believable to some people, and, once in a while, “some people” might just include you!

When 0.1% is more than enough

For example, we received a phish this morning that specifically targeted one of the main South African banks.

(We won’t say which bank by name, as a way of reminding you that it could have been any brand that was targeted, but you will recognise the bank’s own website background image if you are a customer yourself.)

There’s no possible reason for any crook to associate Sophos Naked Security with that bank, let alone with an account in South Africa.

So, this was obviously a widely-spammed out global phishing campaign, with the cybercriminals using quantity instead of quality to “target” their victims.

Let’s do some power-of-ten approximations to show what we mean.

Assume the population of South Africa is 100 million – it’s short of that, but we are just doing order-of-magnitude estimations here.

Assume there are 10 billion people in the world, so that South Africans make up about 1% of the people on the planet.

And assume that 10% of South Africans bank with this particular bank and use its website for their online transactions.

At a quick guess, we can therefore say that this phish was believable to at most 1-in-1000 (10% of 1%) of everyone on earth.

It’s tempting, from there, to extrapolate that 99.9% of all phishing emails will give themselves away immediately.

Then, you might wonder to yourself, perhaps with just a touch of smugness, “If 99.9% of them are utterly trivial to detect, how hard can the other 0.1% be?”

On the other hand, the crooks knew all along that 999 people in every 1000 who received this email would know at once that it was bogus and delete it without a second thought…

..and yet it was still worth their while to spam it out.

Are you thinking clearly?

The ultimate believability of phishing scams like this one actually depends on many factors.

These factors include: Do you have an account with the company concerned? Have you done a transaction recently? Are you in the middle of some sort of contract negotiations right now? Did you have a late night? Is your train due in two minutes? Are you thinking clearly today?

After all, the crooks aren’t aiming to fool all of us all the time, just a few of us some of the time.

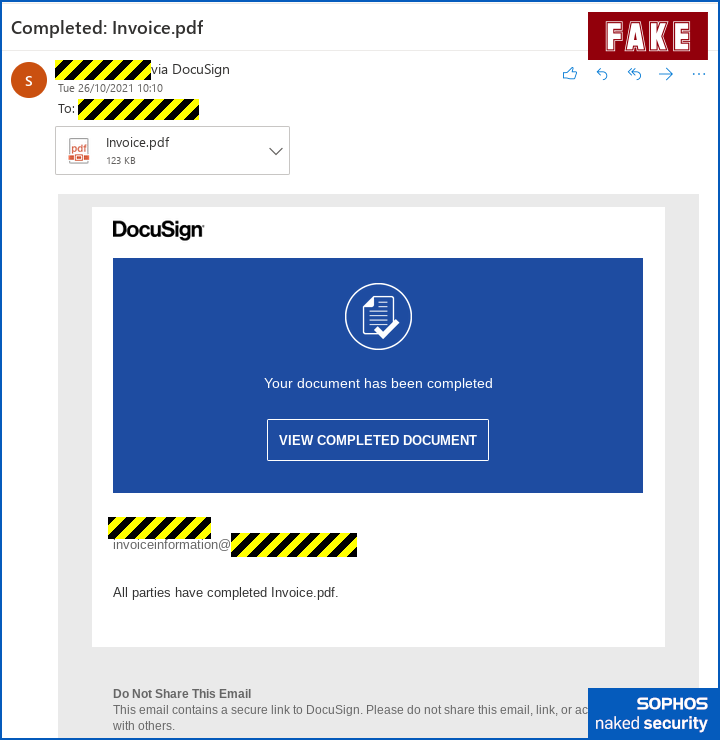

This scam starts, like many phishing scams, with an email:

The email itself comes from cloud-based document and contract-signing service Docusign, and includes a link to a genuine Docusign page. (We have labelled the Docusign screenshot below as FAKE because the content is made up, in the same way we label emails FAKE even if they appear in your trusted email app.)

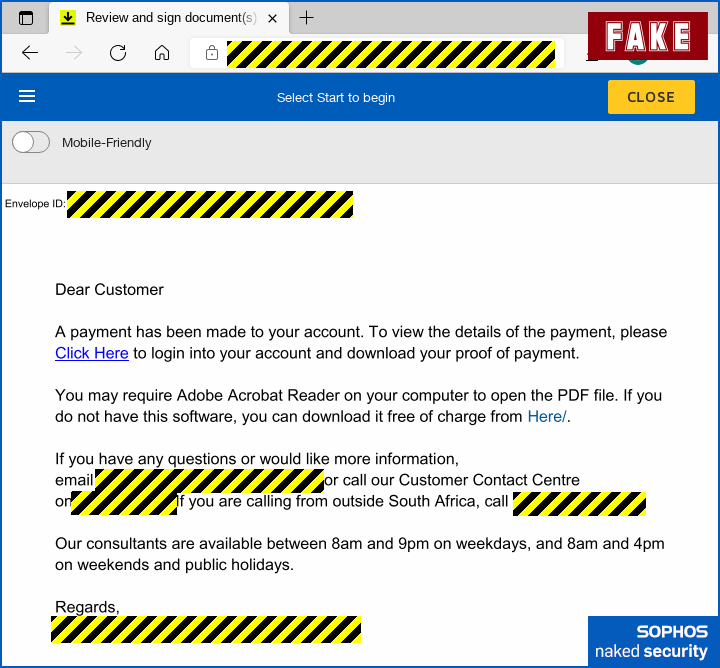

The Docusign page itself isn’t dangerous because it doesn’t contain any clickable links, and just seeing the curious text in it should make you realise that this is just what it seems, a suspicious and unlikely document about nothing:

It’s not a contract, so there’s nothing to identify the person at the other end, or to reveal what the document is about, so the Docusign link is actually a red herring, though it does add a sense of legitimacy-mixed-with-curiosity into the scam.

“Is this some kind of imposter?”, you are probably wondering, “And what on earth are they talking about given that Docusign only has a page for me to view, not an actual contract to process?”

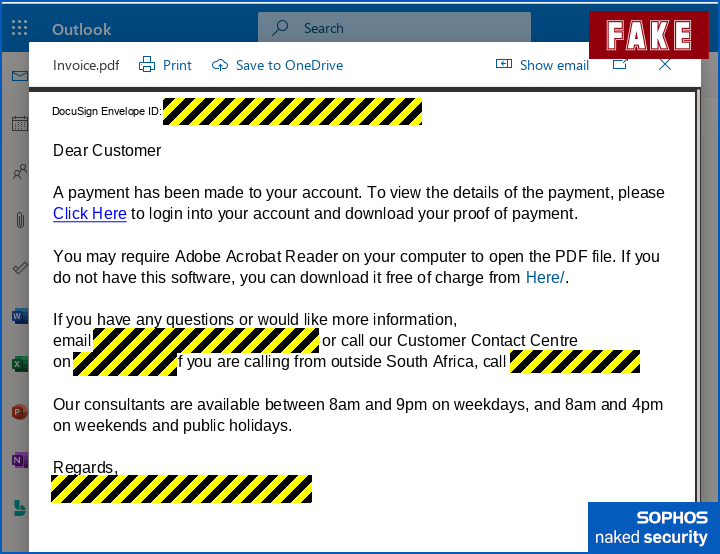

So you might be inclined to open the attached PDF, which is indeed just a replica of the document in the Docusign window:

Except that the link in the PDF version of the document is live, and if you’re still wondering what’s going on, you might be inclined to click it, given that the PDF probably opened in your chosen PDF viewer (e.g. Preview, Adobe Reader or your browser)…

…so it doesn’t feel like the you-know-it’s-risky option of “clicking links in emails” any more.

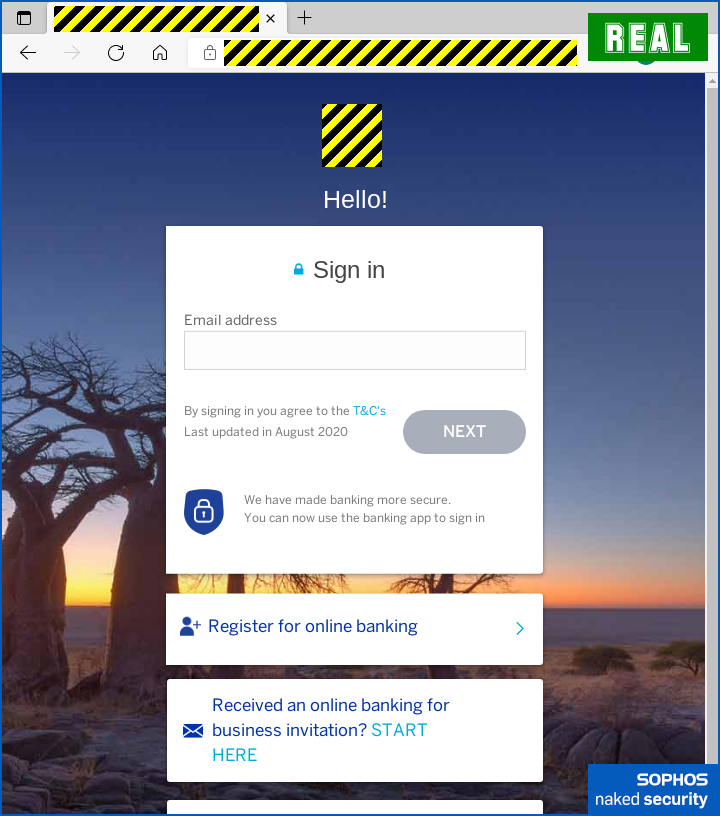

You ought to notice that the URL seems unlikely for a major bank, given that it’s a DNS redirector service in the Philippines, and that the site it redirects to is even more unlikely, given that it’s a hacked agricultural company in Bulgaria.

But one thing is certain, namely that the visuals are surprisingly close to the bank’s regular login page:

Perhaps the bank is trying to draw your attention to a transaction that hasn’t gone through yet, given that you’ve not actually “signed” anything yet via Docusign?

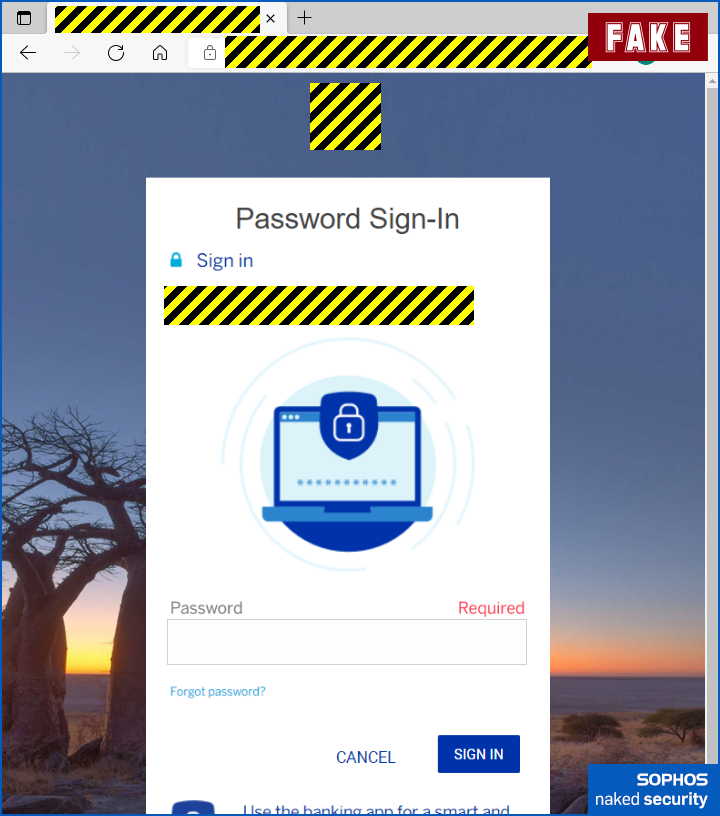

Of course, if you do try to login, the crooks will lead you on a merry but visually agreeable online dance, asking for your password:

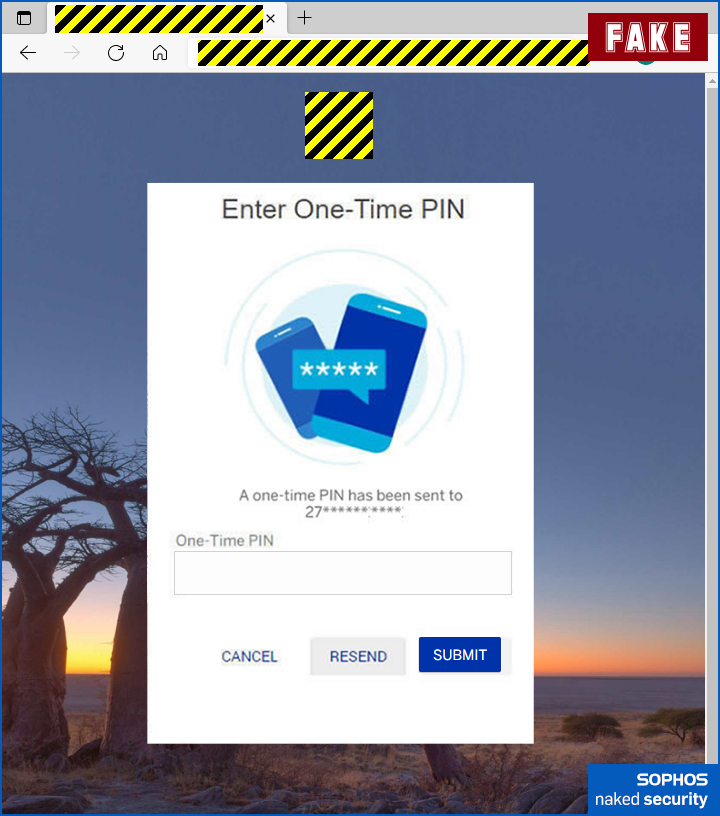

The next step asks for your phone number, so the crooks get that even if the final step fails, followed by a short animated delay, presumably while one of the crooks (if they’re online, or an automated system if they aren’t) starts trying to login using your credentials, followed by a fradulent request for your 2FA code:

If the crooks get this far, and you do enter your 2FA code, then they almost certainly have enough to get into your account.

If all else fails, or it you’re suspicious of handling the matter online, as we hope you would be, there’s a fallback South African phone number listed in the “invoice” that you can call for help.

It’s not the bank’s real call centre, of course – in fact, it’s a VoIP (internet telephony) connection, so you could end up anywhere in the world.

We didn’t try calling it, but we don’t doubt that if you were to do so, the phone would be answered by someone claiming to be from the very bank against which this scam is being worked.

We’re guessing that a polite and helpful person at the other end would simply explain to you how to connect to the fraudulent site by typing in the URL yourself, and patiently wait with you as you went through the process.

That “helpful” person would probably log into the bank with your credentials in parallel with your call, copying the password and 2FA code as soon as you’d handed them over, and then they’d be helping themselves for real, intead of pretending to “help” you.

What to do?

Here are our tips to avoid getting caught out, even if it’s only those 1-in-1000 emails that you need to worry about:

- Check those URLs. Copying the look-and-feel of a brand’s website is easy, but hacking into that brand’s own servers to run the scam is much harder. If you can’t see the URL clearly, for example because you are on a mobile phone, consider switching to a laptop, where details such as full web addresses are much easier to check out.

- Avoid links in emails or attachments. You might be willing to click a Docusign link, assuming you are expecting one and the URL checks out. That means taking what amount to a well-informed risk. But for services such as banks, webmail and courier companies where you already have an account, bookmark the company’s true website for yourself well in advance. Then you never need to rely on links that could have come from anyone, and probably did.

- Use a password manager. Password managers not only choose random, complex and different passwords for every site, so you can’t use the same password twice by mistake, but also associate each password with a specific URL. This means that when you click through to a fake site, the password manager simply doesn’t know which password to use, so it doesn’t try to log you in at all.

- Never call the crooks back. Just as you should avoid links in emails, you should also avoid phone numbers offered by someone you don’t know. After all, whether the number is genuine or not, the person at the other end is going to greet you as though it is. Find the right number to call by looking it up yourself, ideally without using the internet at all, e.g. from existing printed records or off the back of your credit card.

Ivan Petrov

Who is in the right mind would click on URL included in the email that even doesn’t have a user name as a security assurance which is a Bank’s standard email format these days?

In addition, it’s no brainer that much safer to check your account directly via Bank site or mobile app and not through questionable link!

Paul Ducklin

Your name doesn’t really add much or any security, given how much dumped data is out there with name+email combined…

David

I work for a non-profit which provides free legal aid to the poor. We us DocsSign for a wide range of documents between our clients and attorneys. What is NS’s take on DocuSign’s general security?

Paul Ducklin

Apologies for the delay in answering… I missed this comment for a while but did find it when going back and checking :-)

The bottom line is that I haven’t looked into Docusign’s overall security, so I can’t give you any specific advice…

…all I can say is that although this document was delivered as a Docusign file, there was no contract, rogue or otherwise, so from a the viewpoint of “document signing”, there wasn’t a security problem.

So in this case, Docusign is acting more like a mail provider. I don’t think this case tells you anything about the Docusign functionality that you use.

Anonymous

“Here are our tips to avpid getting caught out” – quick typo in there

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks. (I don’t think “avpid” will catch on in the same way as, say, “pwned”.)

Steven

I get more telephone calls than emails now a days. I find it important to have some patience and remember how thing would be and some checking for example if I bought something it will show in my bank statement and my account where I bought it. Sometimes I find it harder to believe the real thing when its a real call from the bank – Its a call about a disaster and they know more about it than I do.

Paul Ducklin

Calls from the bank are a real problem, because they expect you to trust them, even though they have no way of remotely identifying themselves to you over the phone. Yet they often expect you to verify yourself by asking, say, for details of a recent transactions. I’ve argued this with a bank, noting that if there has been fraud againt my account, exactly three people know the details precisely: the bank, me and the crooks. Two of those are on the current call, and of those two I can be certain of the identity of only one of them… me.

My approach has been to ask for a case number and to offer to call back to the number on my card. One bank – and this was a real call from the bank – got a bit shirty and said I was being ureasonable to expect them to hand over “internal” information over the phone, an astonishing and multi-faceted irony. (I ended up going to a branch, where I got much more professional treatment from a bank employee who *did* see the irony.) Another said, “Excellent plan, we aren’t going to give you a callback number over the phone for obvious reasons, we are on the same page.” (Those were not their actual words but the gist is good enough.)