We saw it in a tweet. How about you?

— DEY! (@RoninDey) September 24, 2020

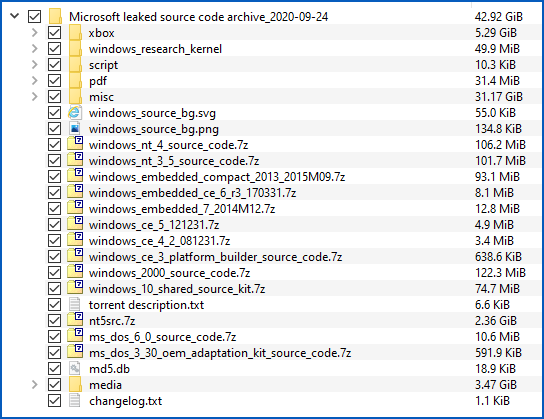

If the reports are to be believed, someone has just leaked a mega-torrent (pun intended – allegedly some of the files have also been uploaded to Kiwi file-sharing service Mega) of Microsoft source code going all the way back to MS-DOS 6.

Zooming in on the image in the abovementioned tweet reveals some interesting artifacts:

OS from filename Alleged source size (bytes)

--------------------- ---------------------------

MS-DOS 6 10,600,000

NT 3.5 101,700,000

NT 4 106,200,000

Windows 2000 122,300,000

NT 5 2,360,000,000

Take these numbers with a pinch of salt, of course – not only are these stolen files, we can’t tell you how complete they are or even if they can be compared at all.

NT 5, for example, covers a whole range of different Windows flavours, officially listed by Microsoft as shown below, so it seems likely that the NT 5 archive includes everything already in the Windows 2000 archive shown above, and more:

OS name Version number

--------------------------- --------------

Windows 2000 5.0

Windows XP 5.1

Windows XP 64-Bit Edition 5.2

Windows Server 2003 5.2

Windows Server 2003 R2 5.2

In case you are wondering, Vista was 6.0, and Microsoft stuck with 6.x for Server 2008, Server 2012 and even, rather weirdly, for the versions outwardly known numerically as Windows 7 and 8.

There was no Windows 9, of course, though we were never exactly sure why, and for Windows 10 the version number took a logical leap forward to 10.0 to match up with the product name. (Server 2016 and Server 2019 are also considered 10.0 releases.)

Intriguingly, Microsoft has officially released old-school source code before, such as when the source of MS-DOS 1.25 (1982) and Word 1.1a (1984) were made public a few years back.

And in recent years, the company has officially and enthusiatically embraced open source for some of its projects, which is where you not only show people your code but also allow them to use it for themselves freely.

But a full and publicly accessible dump of Windows XP source code has never, to our knowledge, happened before.

What does this mean?

The rumour mill suggests that much if not most of this code has been quietly circulating in underground forums for years.

It certainly seems unlikely that a lone hacker suddenly acquired all these files at once, directly from a previously-unknown “mother lode” archive at Microsoft itself.

But as far as we know this is the first claimed Windows XP source code that’s appeared as an all-in-one, come-and-get-it-one-and-all mega-dump.

(We have seen rumours that if you try to compile the 64-bit version of XP you’ll end up with errors caused by missing files, so the archive may not be complete even now.)

So, is this leak a security disaster that will inevitably lead to a raft of new exploits using bugs in XP that are still there in today’s versions of Windows?

Or is it just a mostly harmless, if unlawful, opportunity to take a trip down memory lane, assuming that you have the time, inclination and bandwidth to torrent gigabytes of stolen stuff?

We suspect that it’s more of the latter.

All things being equal, serious security flaws are easier to find if you have commented source code in front of you as well as the compiled binaries.

That’s because you have more to go on if you are on the lookout for flaws such as buffer overflows, dangling pointers (where you free up memory but then carry on using it anyway even after it’s been handed over to someone else), integer arithmetic errors or cryptographic blunders.

Sometimes, the comments alone can help you zoom in on problematic code, especially if you come across snippets where a programmer has left behind reminders such as /* FIX ME!!! */ or // Asked original author but they can't remember if it ever worked properly.

However, experienced bug hunters can find vulnerabilities and exploits without needing source code, as the number of bugs patched each month in products such as Windows and the closed-source parts of macOS, iOS and Android remind us only too well.

Also, even though latent bugs in XP sometimes turn out to have been carried forward all the way to today’s versions of Windows, those bugs are less and less likely still to be exploitable thanks to huge security changes in the core of Windows.

For example, before Windows XP Service Pack 3, pretty much any stack buffer overflow vulnerability you could find in any widely-used Windows application was enough to produce an exploit.

There was no data execution prevention, no address space layout randomisation and almost no other mitigations in place that could soften the blow of a buffer overwite.

If you could overwrite the return address of the current function, you wouldn’t just have a way to crash the running program – you could as good as guarantee to turn the bug into a working remote code execution exploit.

What to do?

If you’re interested in programming, cybersecurity or the history of technology – or even just curious to know what sort of comments Microsoft programmers were apt to write back in the more carefree coding days at the start of the 21st century…

…it’s tempting to take a look.

But unless you really need to look, we’d suggest that you simply let this one go, especially if your interest is just a passingly casual one.

After all, you can’t unsee the code after you’ve looked at it.

And if ever you are in a position where you need to show that you couldn’t possibly have copied someone else’s proprietary code, even if you’d wanted to, you’ll find that harder to do if the other side can show that you definitely did look at it at some point.

Oh, and if you’re a programmer, even if you only ever work on proprietary code that you expect to remain a trade secret for evermore, remember that your code is a little bit like a professional resume:

- Don’t be sloppy.

- Say what you mean.

- Mean what you say.

- You’re probably not quite as witty as you think.

Firstly, you’ll write better code if you keep to these rules.

Secondly, those comments that seemed so wry and amusingly edgy back in the day might not age as well as you thought.

Write your code as though your mum were going to see it, and test it as though she were going to depend upon it.

Because, for all you know, she might very well end up doing both.

Wilderness

Quote of the day!

“Write your code as though your mum were going to see it, and test it as though she were going to depend upon it. Because, for all you know, she might very well end up doing both.”

David Heath

There used to be a similar quote pinned to the wall outside the development team’s area in a small company where I once worked.

“You should write and document your code in the full and clear understanding that the maintenance programmer is an axe-wielding homicidal maniac who knows where you live.”

Dev

“There was no Windows 9, of course, though we were never exactly sure why”

Because of the way previous version of Windows identified itself. There was the potential for legacy software seeing Windows 9 as Windows 95 or Windows 98.

Paul Ducklin

I don’t believe that. IIRC, Windows 95 version numbering followed on from Windows 3.x and denoted itself as Windows 4.xxx. I can’t see how any software version checking code could possibly mistake one for the other. (And legacy code that was soooooo legacy that it would have thought it was on Windows 95 when it was actually running in what is now called Windows 10 would almost certainly have needed compatibility mode turned on for it anyway, if indeed it could even run at all.)

My own assumption is simply that Microsoft thought Windows 10 sounded cooler and more up-to-date (as indeed it does), and that it sounded like (as indeed it turned out to be) a bigger and better leap forward from Windows 8.1 than Windows 9 would have implied.

My 2p.

James

Software version checking code would not get thrown of by the similarity of Windows 9 and Windows 9x, but a search engine would.

Paul Ducklin

No more, surely, than search engines would be thrown off by the similarity of ‘Windows 7’ and ‘Windows 8’, or indeed by ‘9 High Street’ and ’99 High Street’?

Richard

I wouldn’t be so quick to dismiss the possibility. Back when SQL Server 2008 came out, a third-party product we were working with refused to install on it because it required at least SQL Server 2000. Turns out it was doing a string comparison on the version number, and 2008 (v10.0) was less than 2000 (v8.0).

Paul Ducklin

By that argument, Windows 10 (v10.0) would have been a worse choice that Windows 9 (v9.0), because the *version number* of Windows 95 was v4.x, which sorts in a string comparison before v9.0 but after v10.0. So I am still not buying that reason.

Anyway, the Windows APIs don’t return version numbers as strings so it’s hard to see how even a badly-written app could make that sort of mistake for Windows itself. GetVersion(), for example, returns a DWORD.

And Microsoft changed the way you are supposed to check version numbers from Windows 8 onwards so you don’t even need to code the comparison yourself any more. (See “Version Helper functions” in Microsoft’s online docs, e.g. IsWindowsVersionOrGreater(WORD wMajorVersion ,WORD wMinorVersion, WORD wServicePackMajor).)

james nelson

I thought 95 and 98 referred to year of release. After Windows 7 and 8 they decided not to use windows 9 to avoid confusion in human thinking – nothing to do with software confusion.

James.

Paul Ducklin

I buy into the theory that after 8, which people didn’t seem to like much, and then 8.1, which people didn’t seem to think of as an improvement…

…it was useful to jump forward with a version increment of 1.9 instead of a mere 0.9 and avoid people thinking of 9 as merely “next after 8.1, might as well call it 8.2”.

So why not skip a generation altogether? After all, Apple had been offering an operating system called X ( pronounced “ten”, not “ecks” or “decem”) for years.

Of course, macOS 10 (as OS X has been called since about the time Windows 10 came out) will go to 11.0 soon… wonder if Microsoft will do a +2 soon after?

Bryan

Wouldn’t be surprised.

This is reminiscent of the “version jumping” we saw in (IIRC) the early 2000s, where multiple operating system versions were ravaged by a keeping-up-with-the-Joneses-style, accelerated release schedule.

Paul Ducklin

Slackware Linux famously went from 4 to 7 in one go in 1999. As Patrick Volkerding, the Slackware bloke, said at the time, “Sorry if I haven’t been enough of a purist about this. I promise I won’t inflate the version number again (unless everyone else does again ;)”

(He didn’t. He did go 13 -> 13.37 -> 14 many years ago, for fun, but now you just use slackware-current and roll with it, like many distros these days. Does mean you start every morning wondering “will there be a new kernel today?” -very likely – but it seems to work perfectly well just going with the flow and not having a version number.)

Bryan

I actually still have the (purchased) media for Slackware 13.37.

I know I should throw it away, but the geeky angel(?) on my shoulder keeps vetoing that.

Paul Ducklin

I’d keep it. CDs are nice and flat. (I wouldn’t know what to do with one any more. I am not sure where I’d find a computer that could still read them. There’s probably a portable USB CD player in a cupboard somewhere at the office but [a] I’m WFH ATM and [b] which cupboard?)

Bryan

Don’t forget these wise words from the venerable Three Dead Trolls in a Baggie,

And every single version came out late

Paul Ducklin

It depends on what your definition of “late” is.

Bryan

In this case I’ll choose to invoke the “that’s a great song” ruling.

Therefore, any other argument is invalid.

:,)

Thomas Gibson

You guys are arguing over the numbering scheme of a company that, for another product line, released in order: Xbox, Xbox 360, Xbox One, Xbox. It’s more likely that they just count in nonary (Base-9) rather than decimal ;)

Paul Ducklin

Windows 95 and Windows 98 seem to rule out base 9.

John Turner

I was actually part of a group that did Windows Source Code analysis back in the XP days. The developer versions definitely had lots of interesting bugs including kernel level driver issues. Many of them were mitigated with XP SP 3 but definitely not all of them.

At the time, it took a multi processor Xeon box with a ton of memory and disk space to compile the code and it usually took 12-14 hours to make a bootable build.

It’s been a long time since I looked at their source code tree, and I don’t really want to delve back into it. It was definitely an OS built by committee.

Martyn

Microsoft just stole the 10 from Apple. Windows 10 = OS X as OS X is now MacOS

Paul Ducklin

I don’t think it is possible to “steal” the number 10, although I have argued myself that having a version number to equal that of macOS (which is, until the next release, still itself at version 10, just like OS X) would probably have had some marketing appeal. But I would suggest that “skip over 9 to put a little more distance from 8.1” is enough explanation on its own.

Dave Leippe

Windows 10 was initially NT 6.4 while they were technical previews or insider releases. Version 1507 or the RTM came out July 2015 as NT10. Microsoft chose 10 since it was the 10th version of NT.