Emotet is a botnet in its own right, one so prolific and dominant that the United States CERT, the body tasked with tracking cyberthreats to the country, named Emotet in July, 2018 “among the most costly and destructive malware” to affect governments, enterprises and organizations large and small, and individual computer users. According to US-CERT’s alert, Emotet infections have cost state, local, or tribal governments up to $1 million to clean up from a single incident.

The malware uses a series of plugins that can extend its functionality, many of which are designed to steal user information from the infected device, and help the malware move laterally within the network hosting the infected computer. The malware can also, of course, keep itself up to date, and frequently updates itself as long as it is running and can connect to one of its C2 servers.

What are the “native” plugins?

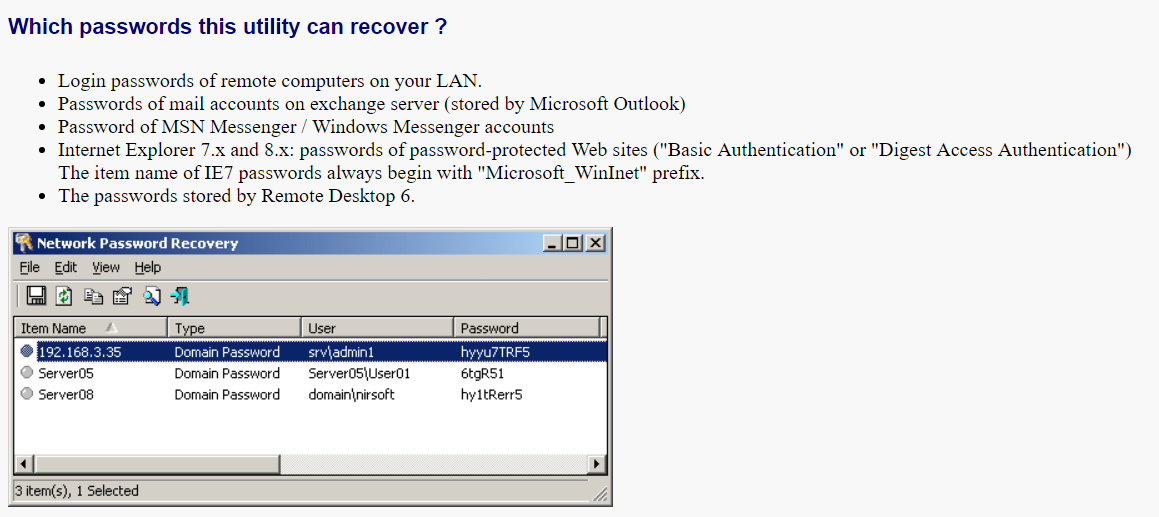

Some of Emotet’s “own” payloads are simply freeware tools (notably, Emotet has used the otherwise-benign NirSoft freeware tools Network Password Recovery and WebBrowserPassView to extract saved network and website passwords) that have been wrapped up in the malware’s encryption and delivered to the victim’s computer.

Some of the locations WebBrowserPassView uses to hunt for saved passwords (or the data files that contain them) are:

Another plugin harvests the contact list from Outlook, and then sends out versions of the original spam used to infect the first victim’s computer to the people that the victim has emailed in the past. The email harvesting module uses the Windows Mail API (MAPI) to collect the email addresses from Outlook.

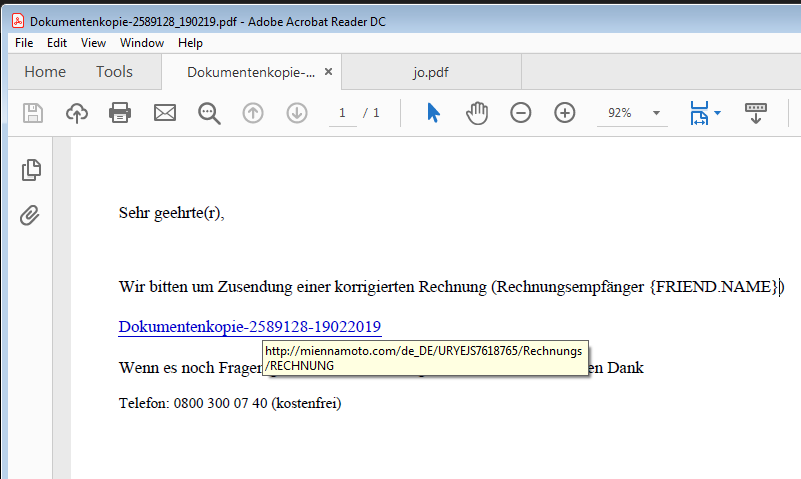

The mail scraper component saves the email addresses to a randomly named .tmp file; When scraping for addresses is complete, the tool passes this file to the spam module as a parameter. The spam module uses that .tmp to build the spam emails on the fly, with a PDF attachment that contains a link to an Emotet installer.

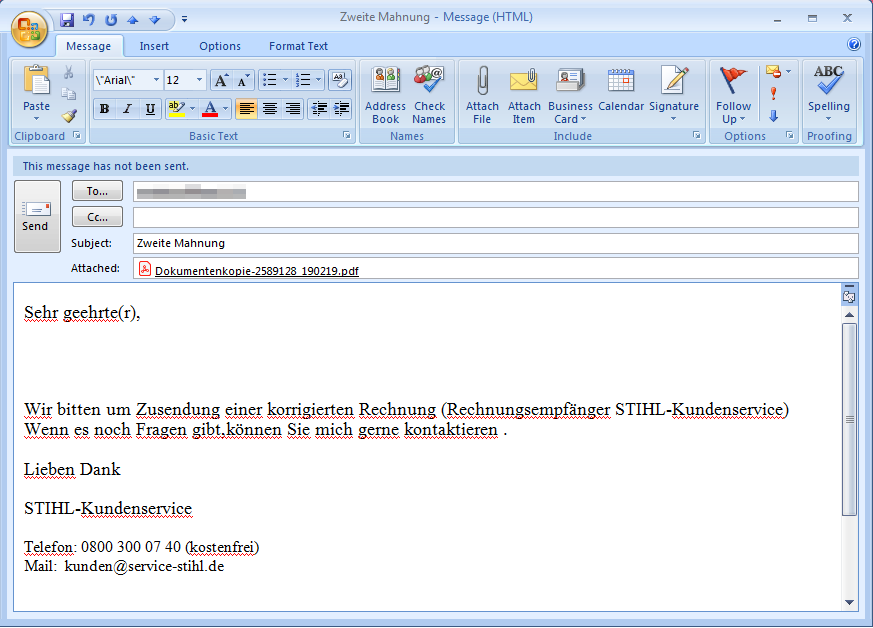

The messages look, essentially, identical to the messages used in the initial attack.

And the PDF attachment, in this case, contains a link to the Emotet installer.

One of Emotet’s most potentially dangerous plugins is called Credential Enumerator. The malware uses this plugin to find Windows (SMB) file shares that are writable by the user account under which the malware is running, or it may try to brute-force the password to shares it finds that it cannot write to. Once it finds a writable share, the component copies itself, then Emotet, to the new share. This form of lateral movement may permit Emotet to infect whole networks of machines.

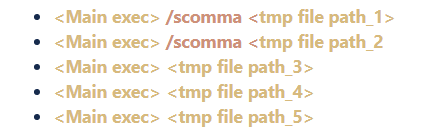

Emotet’s main process performs these steps when it runs: It sets the autorun registry keys and establishes persistence on the infected machine; dynamically loads its DLL payloads; communicates with its C2; creates temporary files to store the passwords and other data it has stolen; and finally creates the following processes (with the CREATE_SUSPENDED flag set) in order to inject itself using WriteProcessMemory.

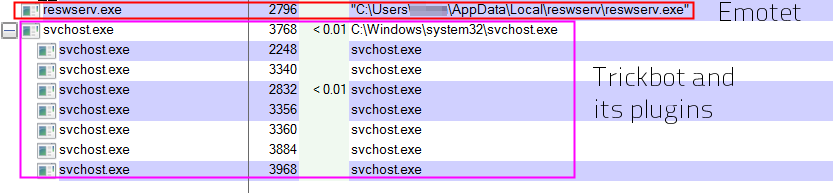

The main Emotet executable creates these processes, injects itself into the process memory, and uses the ResumeThread API function to launch them. The following diagram shows the behavior of the main Emotet executable (named indexersat.exe in this case), spawning these plugins as child processes.

Emotet is a malware delivery vehicle

But this capability to bring other code onto the infected machine serves a still-darker purpose: Emotet acts, in many ways, as a malware distribution network for the makers and operators of many other malware families. Emotet-infected machines routinely get infected with other financially-focused credential hijacking malware, including Qbot, Dridex, Ursnif/Gozi, Gootkit, IcedID, Azorult, Trickbot, or ransomware payloads including Ryuk, BitPaymer, and GandCrab.

While it’s outside the scope of this “101” article to go into detail about these other malware families, it’s safe to say that, on their own, any malware is cause for concern. With Emotet bringing these or other malware into the picture, the potential for serious harm rises.

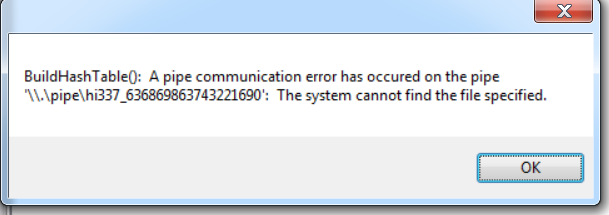

These third-party malware families can, in some cases, load their own plugins. Trickbot is known to do this, but any additional malware samples may also lead to a machine becoming so thoroughly infected with malware that it begins to generate errors or crash randomly. Though this isn’t the intent of the malware authors, victims may notice an increase in the number of alert dialogs warning about unexpected applications crashing, often for no apparent reason. These can happen at any time but are most likely to be noticed by the end user right after a reboot of the infected machine.

These infections carry more than a financial cost on the organizations that suffer through them. In one notable example, a single machine infected with Emotet (and with the assistance of an attacker, who manually bypassed some security controls) resulted in a BitPaymer ransomware infection that spread through government-owned computer networks in the Matanuska-Susitna borough in Alaska last summer, during the peak of its brief tourism season. The ransomware disrupted a wide variety of services in the sparsely populated Mat-Su valley region and some government employees had to pull out and dust off typewriters in order to conduct business while the cleanup took place.

Emotet may be so common, and operate in such a routine manner, that malware experts think of it as somewhat boring, but that’s a mistake. Emotet is a serious malware in its own right, and has the capability (and has shown the propensity) to deliver a bevy of other malware payloads on behalf of criminals who contract with Emotet’s operators to deliver their malware for them.

Acknowledgments

SophosLabs researchers Richard Cohen, Hajnalka Kópé, and Luca Nagy contributed to this research.