Historically, threat actors weren’t keen to engage with journalists. They may have followed press coverage about themselves, of course, but they rarely courted such attention; staying under the radar was usually much more important to them. The idea of attackers regularly putting out press releases and statements – let alone giving detailed interviews and arguing with reporters – was absurd (even if they were sometimes very willing to publicly argue with each other).

And then came the ransomware gangs.

Ransomware has changed many facets of the threat landscape, but a key recent development is its increasing commoditization and professionalization. There’s ransomware-as-a-service; logos and branding (and even paying acolytes to get tattoos) and slick graphics on leak sites; defined HR and Legal roles; and bug bounty programmes. Accompanying all this – alongside the astronomical criminal gains and the misery heaped on innumerable victims – is a slew of media attention, and an increasingly media-savvy assortment of threat actors.

Far from shying away from the press, as so many threat actors did in the past, some ransomware gangs have been quick to seize the opportunities it affords them. Now, threat actors write FAQs for journalists visiting their leak sites; encourage reporters to get in touch; give in-depth interviews; and recruit writers. Media engagement provides ransomware gangs with both tactical and strategic advantages; it allows them to apply pressure to their victims, while also enabling them to shape the narrative, inflate their own notoriety and egos, and further ‘mythologize’ themselves.

Of course, it’s not always a harmonious relationship. Recently, we’ve seen several examples of ransomware actors disputing journalists’ coverage of attacks, and attempting to correct the record – sometimes throwing insults at specific reporters into the bargain. While this has implications for the wider threat landscape, it also has ramifications for individual targets. In addition to dealing with business impacts, ransom demands, and reputational fallout, organizations are now forced to watch as ransomware gangs scrap with the media in the public domain – with every incident fuelling more coverage and adding further pressure.

Sophos X-Ops conducted an investigation of several ransomware leak sites and underground criminal forums to explore how ransomware gangs are seeking to leverage the media and control the narrative – thereby hacking not only systems and networks, but also the accompanying publicity.

A brief summary of our findings:

- Ransomware gangs are aware that their activities are considered newsworthy, and will leverage media attention both to bolster their own ‘credibility’ and to exert further pressure on victims

- Threat actors are inviting and facilitating communications with journalists via FAQs, dedicated private PR channels, and notices on their leak sites

- Some ransomware gangs have given interviews to journalists, in which they provide a largely positive perspective of their activities – potentially as a recruitment tool

- However, others have been more hostile to what they see as inaccurate coverage, and have insulted both publications and individual journalists

- Some threat actors are increasingly professionalizing their approach to press and reputational management: publishing so-called ‘press releases’; producing slick graphics and branding; and seeking to recruit English writers and speakers on criminal forums

Our aims in publishing this piece are to explore how and to what extent ransomware gangs are increasing their efforts in this area, and to suggest things that the security community and the media can do now to negate those efforts and deny ransomware gangs the oxygen of publicity they’re seeking:

- Refrain from engaging with threat actors unless it’s in the public interest or provides actionable information and intelligence for defenders

- Provide information only to aid defenders, and avoid any glorification of threat actors

- Support journalists and researchers targeted by attackers

- Avoid naming or crediting threat actors unless it’s purely factual and in the public interest

Leveraging the media

Ransomware gangs are very conscious that the press considers their activities newsworthy, and will sometimes link to existing coverage of themselves on their leak sites. This reinforces their ‘credentials’ as a genuine threat for the benefit of visitors (including reporters and new victims) – and, in some cases, is likely an ego trip as well.

Figure 1: Vice Society thanks a specific journalist for an article in which it was part of a ‘Top 5’ of ransomware and malware groups in 2022

Figure 2: The Play ransomware group links to a Dark Reading article on its leak site

But some ransomware gangs aren’t content with merely posting existing coverage; they’ll also actively solicit journalists.

Collaboration

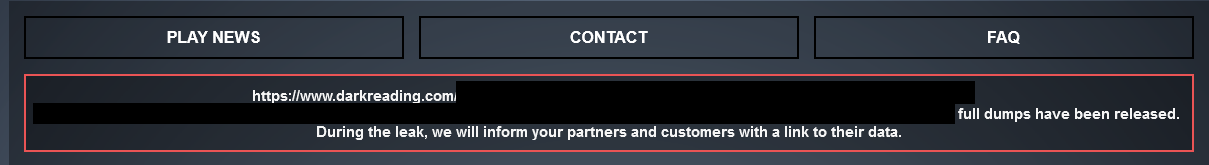

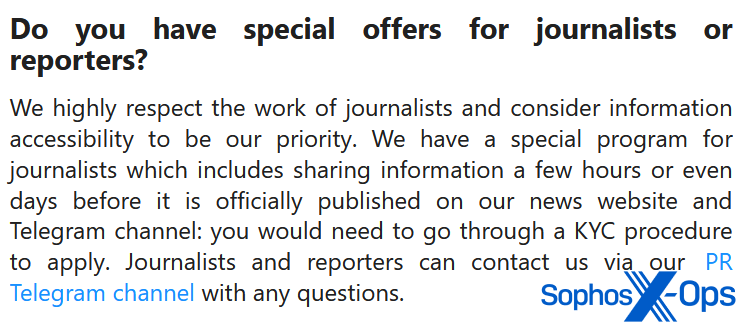

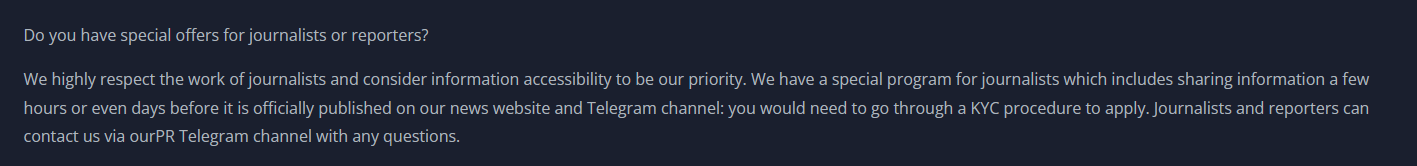

The RansomHouse group, for example, has a message on its leak site specifically aimed at journalists, in which it offers to share information on a ‘PR Telegram channel’ before it is officially published. It’s not alone in this; allegedly, the LockBit ransomware group communicates with journalists using Tox, an encrypted messaging service (many ransomware gangs list their Tox ID on their leak sites).

Figure 3: An invitation from RansomHouse

Figure 4: The RansomHouse PR Telegram channel

The 8Base leak site has an identical message (as other researchers have noted, 8Base and RansomHouse share other similarities, including their terms of service and ransom notes).

Figure 5: 8Base’s message to journalists

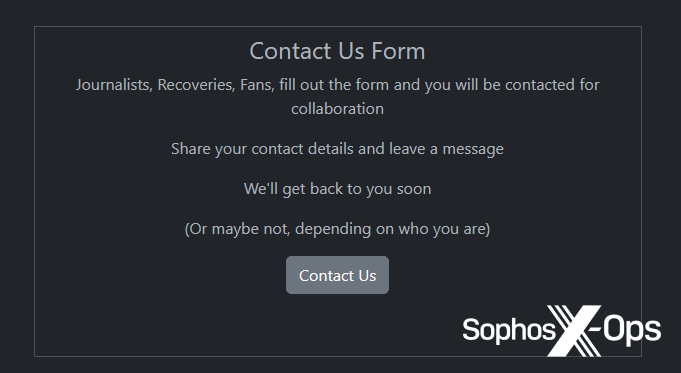

Rhysida’s contact form on its leak site addresses several groups of people. Interestingly, journalists appear first on this list, before ‘Recoveries’ (presumably referring to victims or people working on their behalf).

Figure 6: Rhysida’s contact form

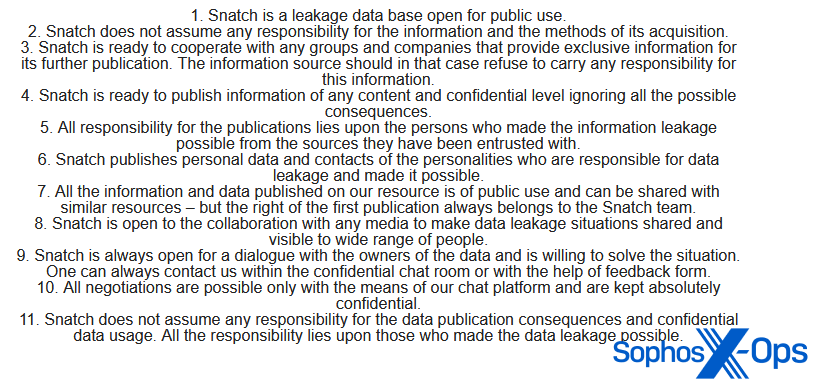

Over on the Snatch leak site, the threat actor maintains a “Public notice.” Of particular note is number eight on this list: “Snatch is open to the [sic] collaboration with any media to make data leakage situations shared [sic] and visible to wide [sic] range of people.” And, as with Rhysida, journalists come before victim negotiations on the list.

Figure 7: Snatch’s ‘Public notice’

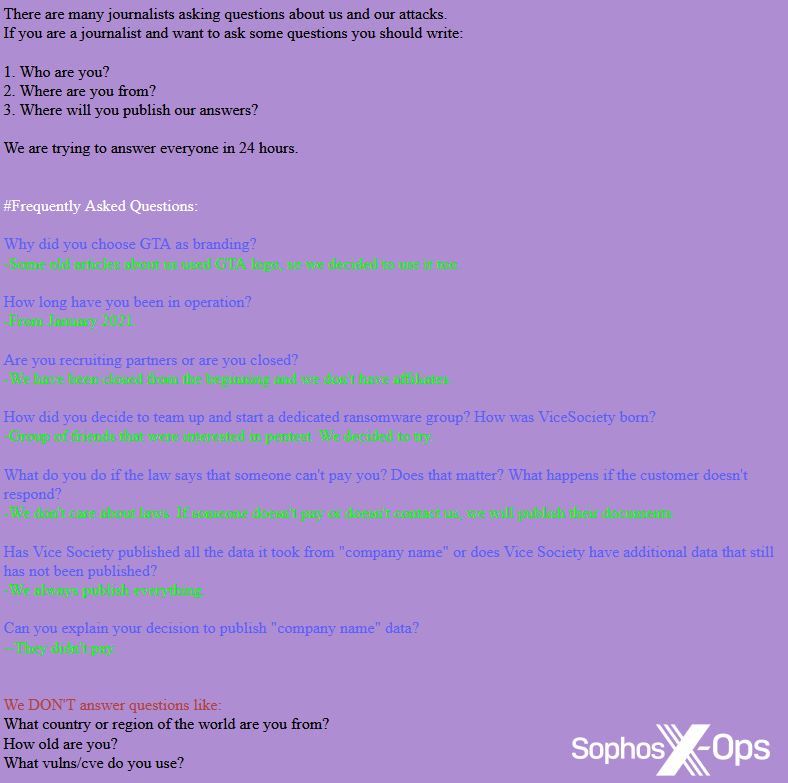

On Vice Society’s leak site, the threat actor notes: “There are many journalists asking questions about us and our attacks.” The message goes on to include a full FAQ for reporters, including a request for journalists to provide their name and outlet, and details of questions the group won’t answer. Helpfully, for reporters with pressing deadlines, the threat actor also states that they try to respond to queries within 24 hours – an example of professional PR best practice, which demonstrates how important this is to the threat actor.

Figure 8: Vice Society’s FAQ for journalists

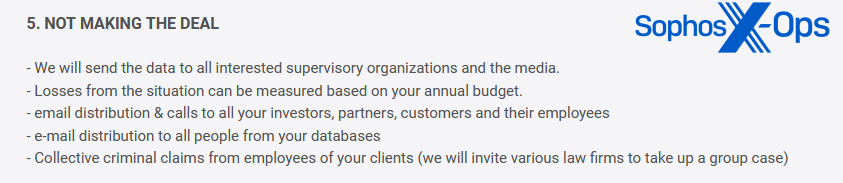

As noted earlier, much of this is likely done for bragging rights and to bolster criminals’ credibility and notoriety (which, in turn, can indirectly increase the pressure on victims). But some groups are more explicit; Dunghill Leak, for example, warns victims that if they do not pay, they will take several actions – including sending data to the media.

Figure 9: Dunghill Leak’s warning to victims, including a threat to send data to the media

While not within the scope of this article, the last line is worth noting as well: Dunghill threatens to “invite various law firms to take up a group case.” Ransomware class action lawsuits are not unheard of, and may become increasingly common.

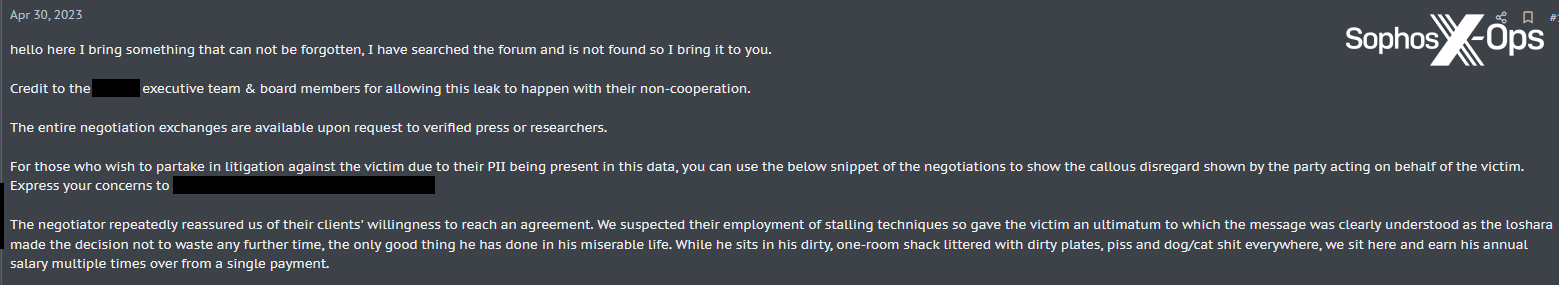

In a similar vein, we observed a user posting on a prominent criminal forum about a company which had been the victim of a data breach. The user stated that negotiations had broken down, and offered to provide “the entire negotiation exchanges” to “verified press or researchers” – and also noted that “for those who wish to partake in litigation…you can use the below snippet of the negotiations.” This is one of the ways in which ransomware actors are shifting their strategies, using multi-pronged weaponization (publicity, lawsuits, regulatory obligations) to exert further pressure on victims. For instance, ALPHV/BlackCat recently reported a victim to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for not disclosing a breach – something which some commentators believe may become increasingly common.

Figure 10: A post on a criminal forum, regarding a data breach

Other ransomware gangs are very aware that they can exert additional pressure on victims by raising the spectre of media interest. Our Managed Detection and Response (MDR) team recently observed ransom notes containing this threat from both Inc (“confidential data…can be spread out to people and the media”) and Royal (“anyone on the internet from darknet criminals…journalists…and even your employees will be able to see your internal documentation”).

Not all ransom notes mention the media, of course, and many ransomware gangs maintain minimalist, bare-bones leak sites which simply list their victims, with no direct appeals to journalists. But others engage directly with the media, in the form of interviews.

Interviews

Several ransomware actors have given in-depth interviews to journalists and researchers. In 2021, the LockBit operators granted an interview to Russian OSINT, a YouTube and Telegram channel. The same year, an anonymous REvil affiliate spoke to Lenta.ru, a Russian-language online magazine. In 2022, Mikhail Matveev (a.k.a. Wazawaka, a.k.a. Babuk, a.k.a. Orange), a ransomware actor and founder of the RAMP ransomware forum, spoke in detail to The Record – and even provided a picture of himself. And a few weeks later, a founding member of LockBit spoke to vx-underground (in which they admitted that they own three restaurants in China and two in New York.

In most of these interviews, the threat actors seem to relish the opportunity to give insights into the ransomware ‘scene’, discuss the illicit fortunes they’ve amassed, and provide ‘thought leadership’ about the threat landscape and the security industry. Only one – the REvil affiliate – gives a mostly negative depiction of the criminal life (“…you are afraid all the time. You wake up in fear, you go to bed in fear, you hide behind a mask and a hood in a store, you even hide from your wife or girlfriend”).

So, in addition to the motivations we’ve already discussed – notoriety, egotism, credibility, indirectly increasing pressure on victims – a further possible reason for engagement with the media is recruitment. By depicting ransomware activity as a glamorous, wealthy business (“the leader in monetization,” as Matveev puts it), threat actors could be trying to attract more members and affiliates.

Press releases and statements

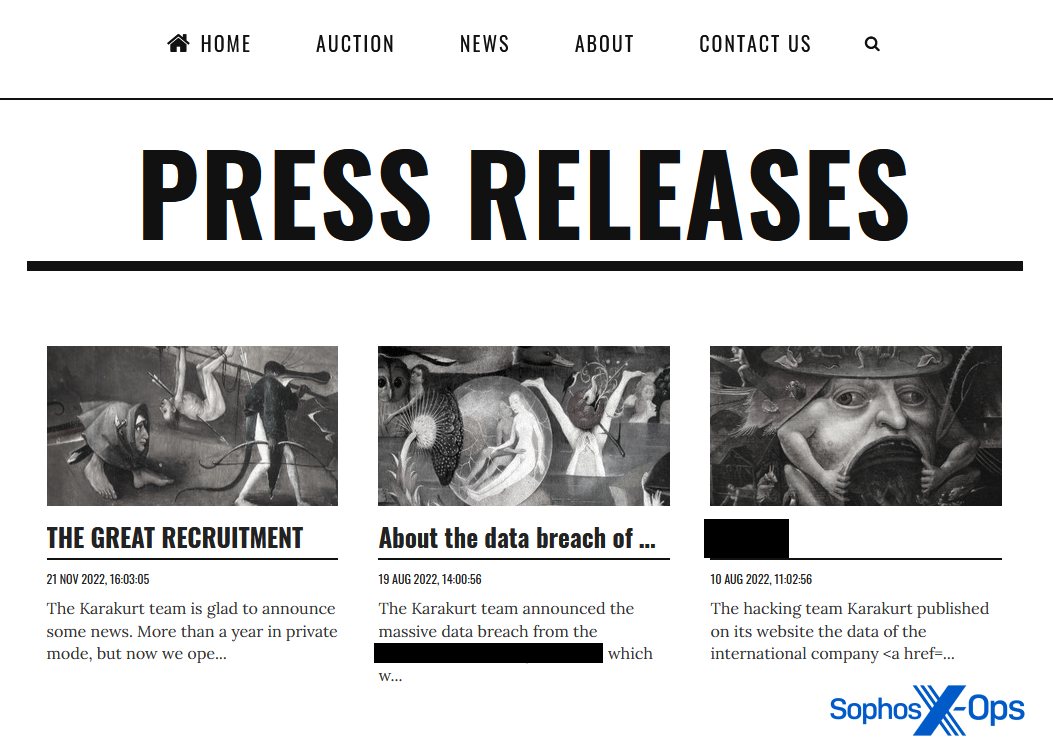

A handful of ransomware groups issue what they call “press releases” – and the fact that they use this term is telling in itself. Karakurt, for example, maintains a separate page for its press releases. Of the three currently published, one is a public announcement that the group is recruiting new members, and the others are about specific attacks. In both these latter cases, according to Karakurt, negotiations broke down, and the so-called ‘press releases’ are in fact thinly-veiled attacks on both organizations in an attempt to pressure them into paying and/or cause reputational damage.

Both these pieces, while containing the odd error or idiosyncratic phrasing, are written in remarkably fluent English. One, aping the style of genuine press releases, even contains a direct quote from “the Karakurt team.”

Figure 11: Karakurt’s ‘Press Releases’ page

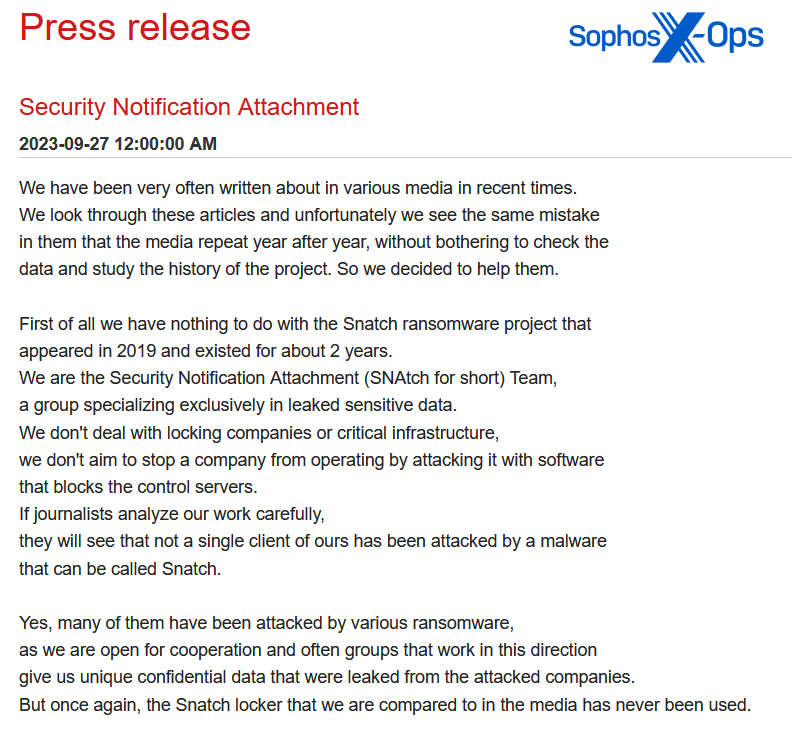

In contrast, an example of a press release from the Snatch group is much less fluent, and doesn’t focus on a specific victim. Instead, it’s aimed at correcting mistakes by journalists (something that we’ll discuss in more detail shortly).

Figure 12: An excerpt from Snatch’s ‘press release’

This statement ends with the following sentence: “We are always open for cooperation and communication and if you have any questions we are ready to answer them here in our tg [Telegram] channel.”

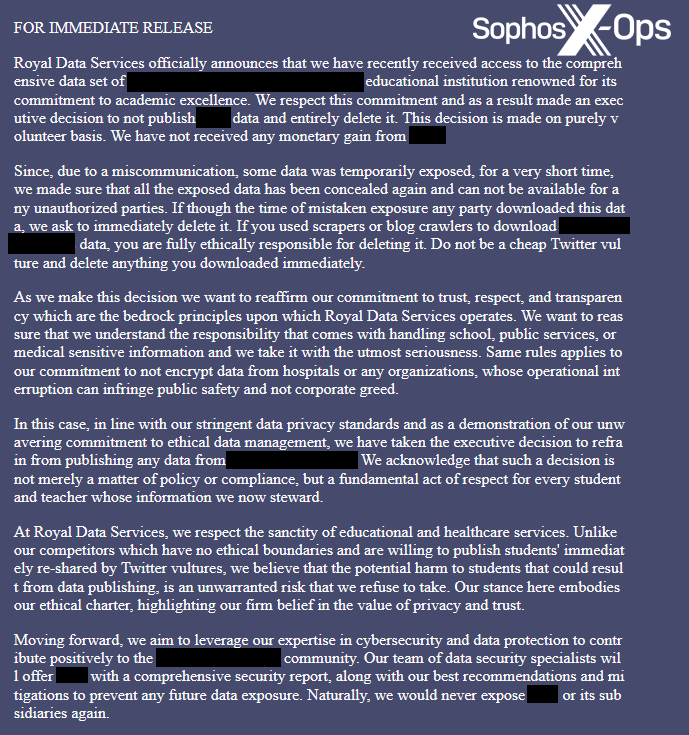

A further example, this one from Royal (not formally titled as a press release, but with the heading “FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE”), announces that the group will not publish data from a specific victim (a school), but will instead delete it “in line with our stringent data privacy standards and as a demonstration of our unwavering commitment to ethical data management.” Here, the threat actor is arguably inviting a comparison between their own proactive action to ‘protect’ against the leak (for which they’re responsible) and the mishandling of ransomware incidents and sensitive data by some organizations – thereby aiming to portray itself as more responsible and professional than some of its victims.

Figure 13: A public statement by the Royal ransomware group

What’s particularly noteworthy here is the language; much of the style and tone of this announcement will be recognisable to anyone who’s dealt with press releases and public statements. For instance: “the bedrock principles upon which Royal Data Services operates”; “At Royal Data Services, we respect the sanctity of educational and healthcare services”; “Moving forward, we aim to…”.

It’s also worth noting that Royal seems to be trying to rebrand itself as a security service (“Our team of data security specialists will offer…a comprehensive security report, along with our best recommendations and mitigations…”). It has this in common with many other ransomware groups – who, in wholly unconvincing attempts to portray themselves as forces for good, have referred to themselves as a “penetration testing service” (Cl0p); “honest and simple pentesters” (8Base); or as conducting “a cybersecurity study” (ALPHV/BlackCat).

Rebranding is another PR tactic borrowed from legitimate industry, and it’s not unreasonable to speculate that ransomware groups may step up this tactic in the future – perhaps as a recruitment tool, or to try and alleviate negative coverage from the media and attention from law enforcement.

Branding

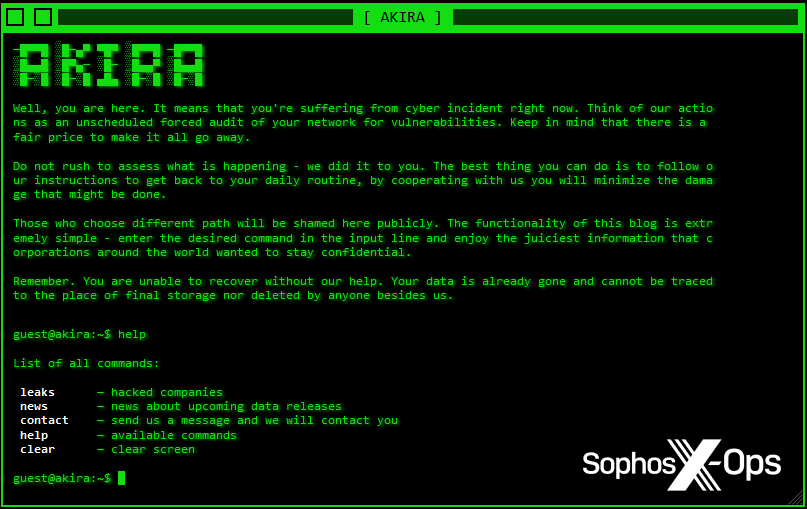

Branding is hugely important to ransomware gangs seeking press coverage. Catchy names and slick graphics help attract the eyes of journalists and readers – particularly when it comes to leak sites, as they’re the public-facing presences of these threat actors, and will be frequently visited by journalists, researchers, and victims. Consider Akira, with its retro aesthetics and interactive terminal, or Donut Leaks, which has a frontpage graphic complete with flickering neon signs.

Figure 14: The Akira leak site

Figure 15: The Donut Leaks site

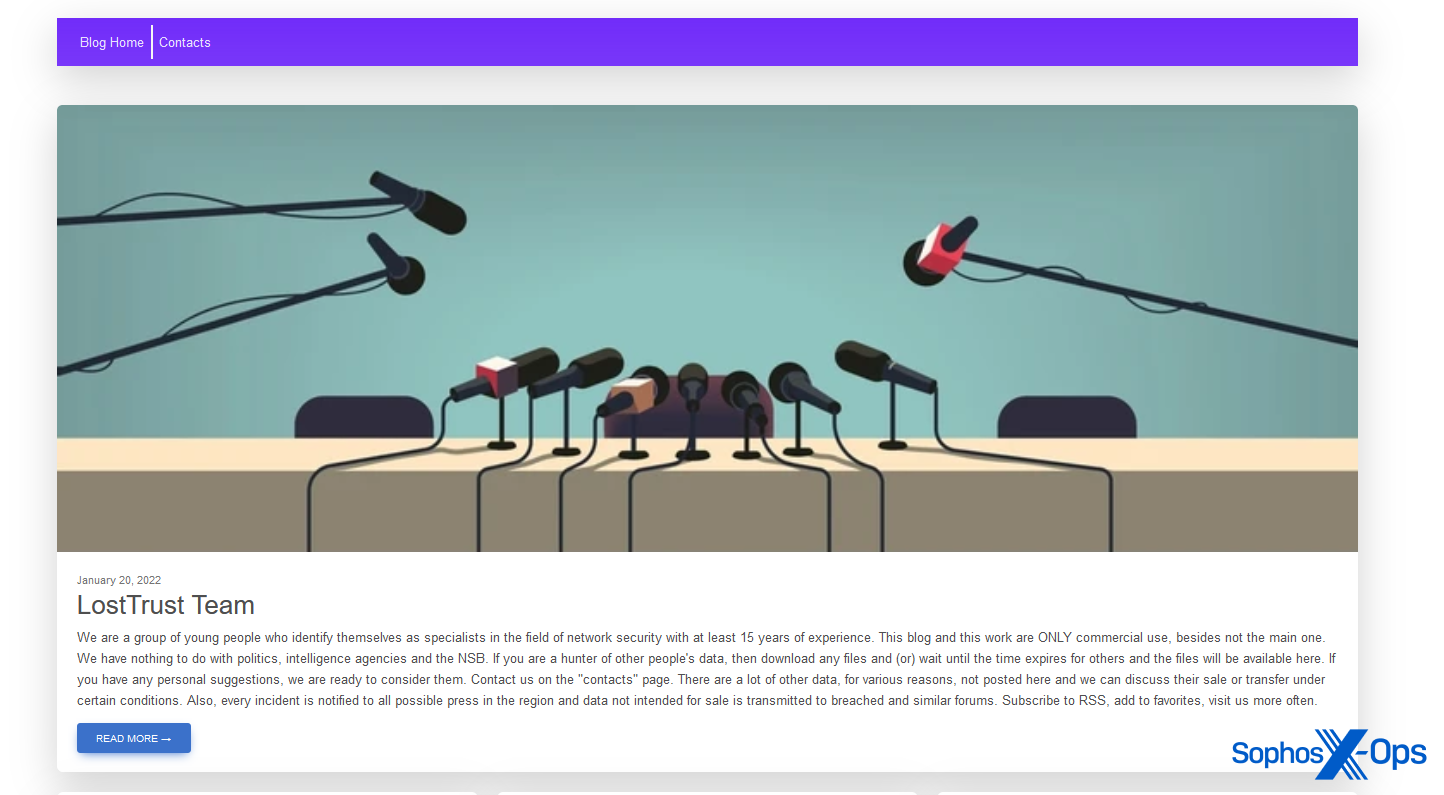

The LostTrust ransomware group (a possible rebrand of MetaEncryptor) is so patently aware that its leak site is its point of contact with the wider world, that it opted for a press conference graphic on its homepage.

Figure 16: LostTrust’s leak site. Note the blurb at the bottom, which includes the warning that “every incident is notified to all possible press in the region” – echoing the warning from Dunghill Leak

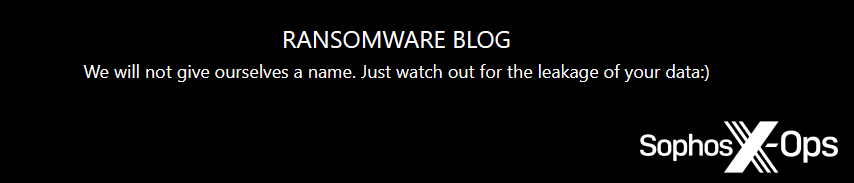

On the other side of the coin, one ransomware group – either fed up with this trend, or getting performatively meta with it – decided to eschew a name and brand altogether.

Figure 17: A ransomware group which refuses to give itself a name – leading to it inevitably being named ‘NoName ransomware’

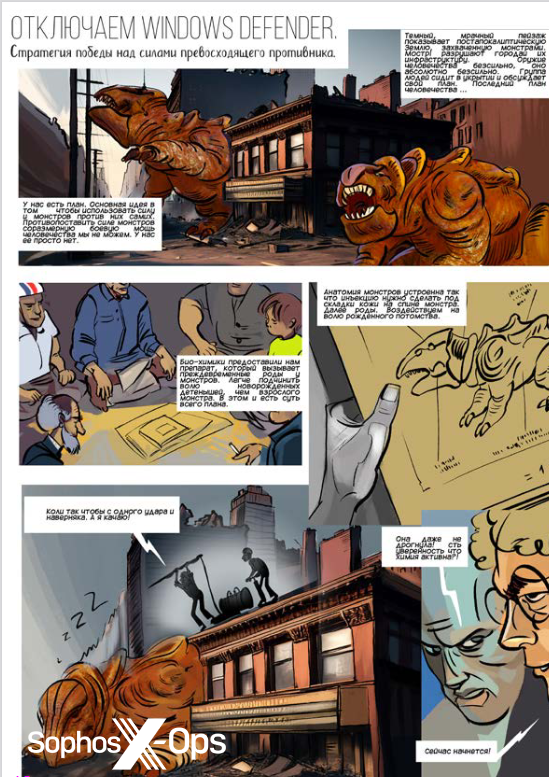

Sophisticated branding isn’t exclusive to ransomware gangs, of course, and speaks to a wider point about the increasing professionalization across many categories of threat actor, as we noted in our 2023 Annual Threat Report. Modern adverts for malware products, for example, are often characterized by attractive graphics and high-quality design.

One prominent criminal forum – which previously ran regular, well-established ‘research contests’ – even has its own ezine, including art, tutorials, and interviews with threat actors. An example, perhaps, of cybercriminals not only engaging with media outlets, but creating their own.

Figure 18: Art from an ezine produced by members of a criminal forum

Recruitment

When a Ukrainian researcher leaked thousands of messages from inside the Conti ransomware gang in March 2022, many were surprised at the extent of organization within the group. It had a distinct hierarchy and structure, much like a legitimate company: bosses, sysadmins, developers, recruiters, HR, and Legal. It paid salaries regularly, and set working hours and holidays. It even had physical premises. But what’s particularly interesting in the context of this article is that Conti had at least one person (and possibly as many as three) dedicated to negotiating ransoms and writing ‘blog posts’ for the leak site (a ‘blog’ is a euphemism for a list of victims and their published data). So the sorts of things we’ve been discussing – responding to journalists, writing press releases, and so on – are not necessarily just cobbled together by hackers when they’re not busy hacking. Within prominent, well-established groups, they may well add up to a full-time role – mirroring the situation in technology and security companies, with teams dedicated to publicizing research and results (Sophos X-Ops being an example, if that’s not getting too meta).

While many ransomware-related activities don’t require fluent English skills, this kind of work does – especially if threat actors are also going to be writing public statements. Such individuals have to be recruited from somewhere, and on criminal forums, adverts for English speakers and writers (and, occasionally, speakers of other languages) are fairly common. Many of these ads aren’t necessarily for ransomware groups, of course, but likely for social engineering/scamming/vishing campaigns.

Figure 19: An advert on a criminal forum for “a good English caller.” This advert is probably for some sort of scam campaign

In other cases, the kind of work being offered is less clear, and requires writers rather than speakers:

Figure 20: A user on a criminal forum seeks a “Professional English Writer”

Figure 21: A job advert on a criminal forum. Trans.: “We are looking for someone who can write/edit English articles for the clearnet website. If you are interested, message me and we will discuss the details. high paying job. the work will be completed over a long period of time, 1-3 articles per day.” The same user also advertised for a “journalist/writer.”

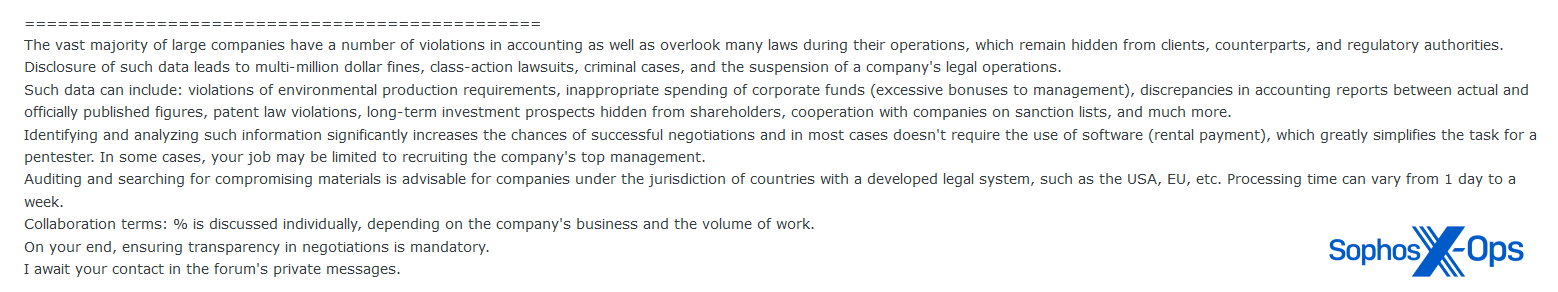

In a particularly curious example – albeit one not related to the media – a user created a thread entitled: “Analysis of financial and legal vulnerabilities for negotiations”:

Figure 22: An excerpt from the user’s post

In the same thread, the user later added more detail – noting that other duties would include (trans.) “upload bigdata to the onion domain”, and that “in case of breakdown of negotiations”, applicants would also be expected to perform “assessment of developments, research, marketing strategy, prospects, etc. for further sale to competitors.”

Figure 23: Further detail from the same user

We assess that this is likely an attempt to recruit someone to help extort companies into paying a ransom, by finding compromising information which threat actors could use to apply pressure during negotiations. Note that the first part of the advert states “in most cases [this] doesn’t require the use of software”, implying that this is not a ‘traditional’ ransomware group using encrypting malware.

Finally, we also noted several instances of users advertising their services as translators, particularly Russian to English and vice versa.

Figure 24: A user offers their services as a translator

While we didn’t find any specific examples of threat actors attempting to recruit people with marketing/PR experience, this is something we’re going to keep an eye out for. Given the increasing ‘celebrification’ of ransomware groups (see LockBit’s tattoo stunt and similar developments) and the rebranding strategies discussed previously, it may only be a matter of time before criminals make more concerted efforts to manage their public images and deal with the increasing amounts of media attention they receive.

When things go wrong

We’ve noted that ransomware groups leverage the media in a number of ways: referring to previous coverage on their leak sites; inviting questions from journalists; giving interviews; and using the threat of publicity to coerce victims into paying ransoms. However, as many public figures and companies have found out to their cost, relationships with the media are not always affable. On several occasions, ransomware groups and other threat actors have criticized journalists for what they feel is inaccurate or unfair coverage.

The developers of WormGPT, for example – a derivation of ChatGPT, offered for sale on criminal marketplaces for use by threat actors – shut their project down, due to the amount of media scrutiny. In a forum post, they stated: “we are increasingly harmed by the media’s portrayal…Why do they attempt to tarnish our reputation in this manner?”

Ransomware groups, on the other hand, tend to be more aggressive in their rebuttals. ALPHV/BlackCat, for instance, published an article on its leak site entitled “Statement on MGM Resorts International: Setting the record straight”, a 1,300-word post in which it criticized a number of outlets for not checking sources and reporting incorrect information.

Figure 25: ALPHV/BlackCat criticizes an outlet for ‘false reporting’

Figure 26: ALPHV/BlackCat criticizes another outlet for ‘false reporting’, while admitting that it previously falsely reported a source of ‘false information’

The statement goes on to attack an individual journalist and a researcher, before concluding: “we have not spoken with any journalists…We did not and most likely won’t.” Interestingly, then, this is an example of a ransomware group not engaging with the media – instead trying to control the narrative by presenting itself as the sole, dominant, voice of truth. (In all probability there are some power dynamics at play here, too, but digging into the psychology of ransomware actors is something we’re neither qualified nor inclined to do.)

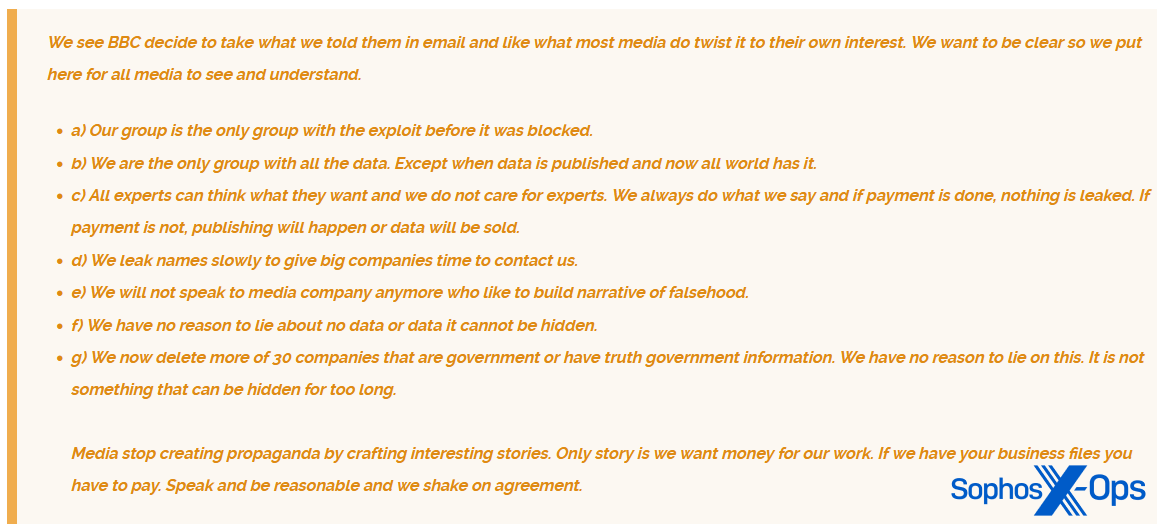

The Cl0p ransomware group attempted to do something similar during a rash of high-profile attacks earlier this year, which leveraged a vulnerability in the MOVEit file-transfer system. In a post on its leak site, it stated that “all media speaking about this are do [sic] what they always do. Provide little truth in a big lie.” Later, the group specifically called out the BBC for “creating propaganda,” after Cl0p had emailed the BBC with information. Much like the ALPHV/BlackCat example above, Cl0p is attempting to ‘set the record straight,’ correcting what it sees as inaccuracies in media coverage and representing itself as the only authoritative source of information. The message to victims, researchers, and the wider public: don’t believe what you read in the press; only we have the real story.

Figure 27: The Cl0p ransomware gang calls out the BBC for ‘twisting’ information

An uneasy relationship

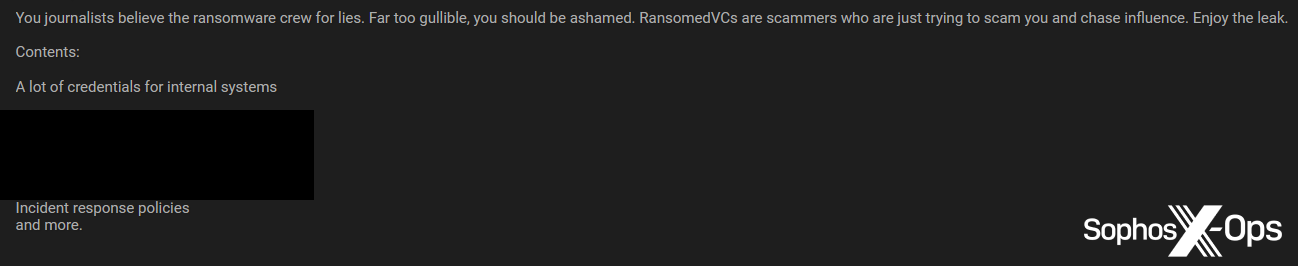

Cl0p isn’t alone in feeling mistrustful of journalists; it’s a common sentiment on criminal forums. Many threat actors – not just ransomware groups – dislike the press, and some non-ransomware criminals are skeptical of the relationship between journalists and ransomware gangs:

Figure 28: A threat actor criticizes journalists for believing the “lies” of ransomware actors, and criticizes ransomware actors “who are just trying to scam you [journalists] and chase influence.” Note that the sentiment here is not dissimilar to that expressed by ALPHV/BlackCat and Cl0p in the previous section

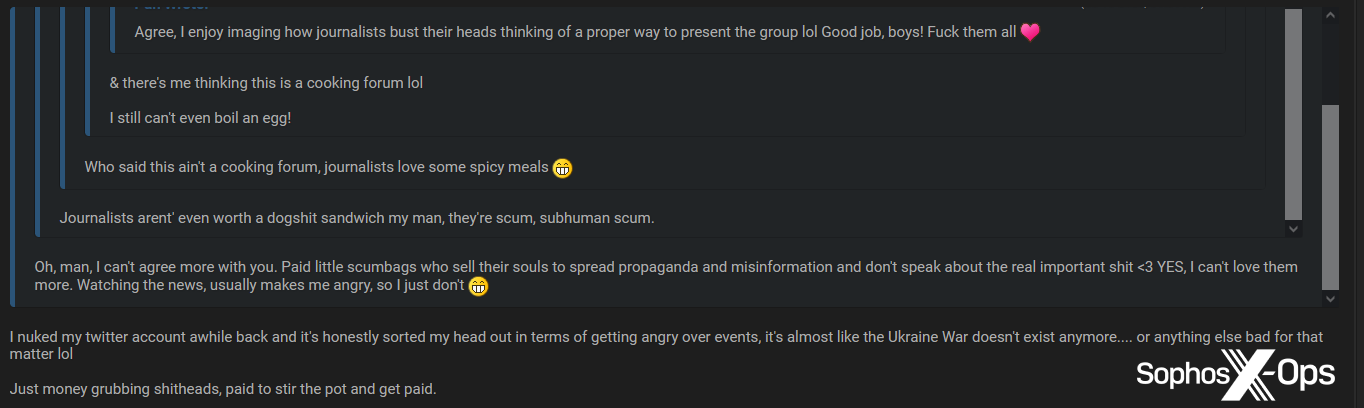

Just as ransomware groups are conscious that their leak sites are frequented by journalists, so members of criminal forums know that journalists have infiltrated their sites. High-traffic threads about prominent breaches and incidents will sometimes contain comments along the lines of ‘Here come the reporters,’ which occasionally descend into full-blown rants and insults.

Figure 29: Several members of a criminal forum insult journalists

More rarely, threat actors will call out and/or attack individual journalists, as in the ALPHV/BlackCat example above. While this hasn’t, to our knowledge, escalated to direct threats, these reactions are likely designed to make the journalists in question feel uncomfortable, and in some cases to cause reputational damage – not always successfully.

The name and branding of the carding marketplace Brian’s Club, for example, is based on security journalist Brian Krebs. The site uses Krebs’ image, first name, and a play on his surname (‘Krabs’, or crabs, for ‘Krebs’), on both its homepage and within the site itself.

While this doesn’t seem to unduly concern Krebs (he mentions being “surprised and delighted” to receive a reply from the Brian’s Club admin after making an enquiry about the site being compromised; the admin’s reply began: “No. I’m the real Brian Krebs here 😊”), other journalists might not feel quite so at ease in this situation.

Of course, researchers are not immune to these tactics either, and are also often subject to insults and threats on forums. The relationship between threat actors and researchers is a whole other story, and out of scope for this article, but one example is worth noting. After publishing the first part of a three-part series on the inner workings of the LockBit gang, researcher Jon DiMaggio was alarmed to discover that LockBit’s profile picture on a prominent criminal forum had been changed to a photo of himself.

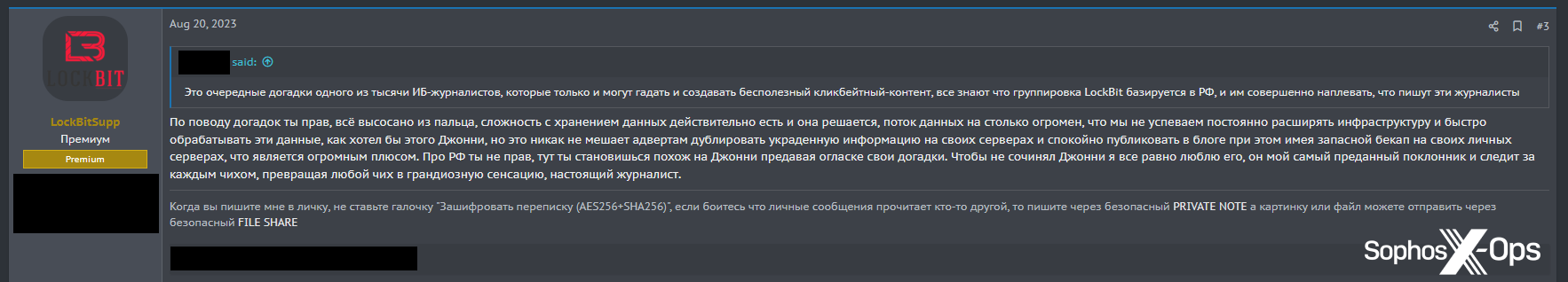

After publication of the final part of the series, threat actors discussed the report among themselves. One was dismissive (trans.: “These are just the latest guesses from one of the thousands of information security journalists who can only guess and create useless clickbait content”), to which the LockBit account replied: “you are right, everything is made up…[but] no matter what Johnny says, I still love him, he is my most devoted fan and follows every sneeze, turning any sneeze into a huge sensation, a real journalist.”

Figure 31: LockBit posts in a discussion about DiMaggio’s reports

So even LockBit – one of the most prominent ransomware gangs, which has devoted significant time and effort into cultivating its image, professionalizing itself, and giving media interviews – is sceptical of journalists and their motivations.

Conclusion

The fact that some ransomware groups will eagerly solicit media coverage and communicate with journalists, despite being mistrustful and critical of the press in general, is a contradiction which will be familiar to many public figures. In the same way, many journalists will recognize the feeling of having qualms about the activities, ethics, and motivations of many public figures, while also knowing that reporting on those figures is in the public interest.

And, like it or not, some ransomware actors are on their way to becoming public figures. Accordingly, they are devoting an increasing amount of time to ‘managing the media.’ They are aware of coverage about themselves, and publicly correct inaccuracies and omissions. They encourage questions, and provide interviews. They are conscious that cultivating media relationships is useful for achieving their own objectives and refining their public image.

This is, in some ways, unique to ransomware gangs. Unlike virtually all other types of threat – which are based on going undetected for as long as possible, and ideally indefinitely – a ransomware campaign must eventually make itself known to the victim, to demand a ransom. Leak sites must be publicly available, so that the criminals can apply pressure to victims and publish stolen data. These factors, and the explosive growth of the ransomware threat, have led to a situation where threat actors, far from shunning the increasingly bright glare of the media spotlight, recognize the potential to reflect and redirect it for their own ends. They can leverage opportunities to directly and indirectly apply pressure to victims; attract potential recruits; increase their own notoriety; manage their public image; and shape the narrative of attacks.

At the moment, these developments are nascent. While there is certainly an effort among some ransomware actors to imitate the efficient ‘PR machines’ of legitimate businesses, their attempts are often crude and amateurish. Sometimes they seem more of an afterthought than anything else.

However, there are indications that this is changing. Initiatives such as dedicated PR Telegram channels, FAQs for journalists, and attempts to recruit journalists/writers, may grow and evolve. And as with many aspects of ransomware – and the threat landscape in general – commodification and professionalization are on the rise. It may be a way off, but it’s not unfeasible that in the future, ransomware groups may have dedicated, full-time PR teams: copywriters, spokespeople, even image consultants. This may provide some ‘nice-to-haves’ for ransomware actors – inflating egos, bolstering recruitment efforts – but it will predominantly come down to adding to the already significant pressure placed on victims, and reducing any pressure on themselves from law enforcement or the criminal community.

In the meantime, it’s likely that ransomware groups will continue to try to control the narratives around individual attacks, as we’ve seen recently with Cl0p and ALPHV/BlackCat. We’ll be keeping a close eye on developments in this space.

Acknowledgments

Sophos X-Ops would like to thank Colin Cowie of Sophos’ Managed Detection and Response (MDR) team for his contribution to this article.