In January 2021, reports surfaced of a backup-busting ransomware strain called Deadbolt, apparently aimed at small businesses, hobbyists and serious home users.

As far as we can see, Deadbolt deliberately chose a deadly niche in which to operate: users who needed backups and were well-informed enough to make them, but who didn’t have the time or funds to give their backup routine the attention it really deserved.

Many ransomware attacks unfold with cybercriminals breaking into your network, mapping out all your computers, scrambling all the files on all of them in unison, and then changing everyone’s wallpaper to show a blackmail demand along the lines of, “Pay us $BIGVAL and we’ll send you a decryption key to unlock everything.”

For large networks, this attack technique has, sadly, helped numerous audacious criminals to extort hundreds of millions of dollars out of organisations that simply didn’t have any other way to get their business back on track.

Deadbolt, however, ignores the desktops and laptops on your network, instead finding and attacking vulnerable network-attached storage (NAS) devices directly over the internet.

To be clear, the decryption tools delivered by today’s cybercriminals – even when the amount involved is hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars – routinely do a mediocre job. In our State of Ransomware 2021 survey, for example, half of our respondents who paid up nevertheless lost at least a third of their data. In fact, a third of them lost more than half of the data they paid to recover, and a disastrously disappointed 4% paid full price but got nothing back at all.

No lateral movement required

By exploiting a security vulnerability in QNAP products, the Deadbolt malware didn’t need to get a foothold on your laptop first, and then to spread sideways through your home or business network.

A remote code execution (RCE) hole identified in QNAP’s security advisory QSA-21-57 could be exploited to inject malicious code directly onto the storage device itself. (Like many internet-connected hardware devices, the affected products run a customised Linux distribution.)

So, if you’d inadvertently set up your backup device so that its web portal was accessible from the “internet side” of your network connection – the port that’s probably labelled WAN on your router, short for wide-area network – then anyone who knew how to abuse the security hole patched in QSA-21-57 could attack your backup files with malware.

In fact, if you were in the habit of looking at your device only when you needed to recover or review files you didn’t have space to keep “live” on your laptop, you might not have realised that your files had been scrambled until you next went to the web interface of your NAS.

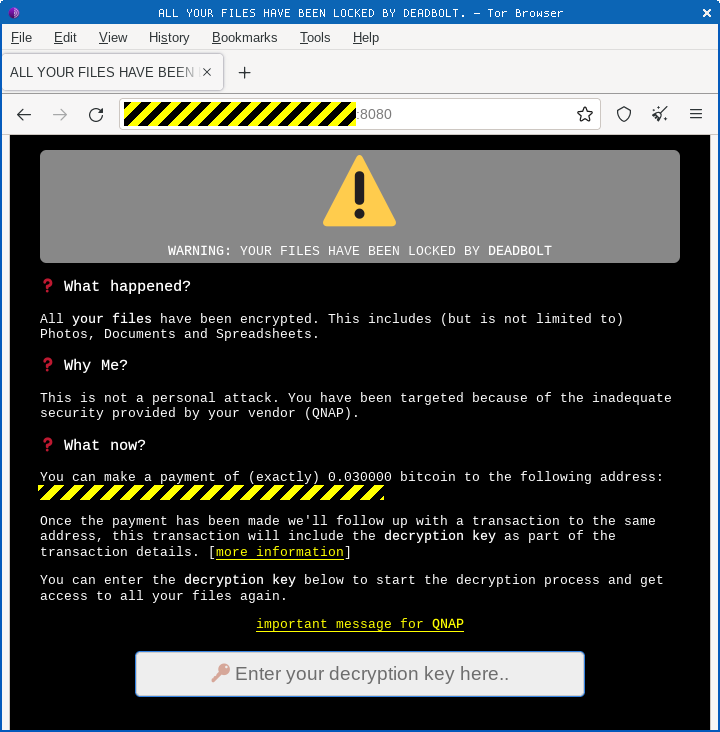

When you got there, however, you’d be in no doubt at all what had happened to your data, because the Deadbolt attackers deliberately modified the portal page of the NAS itself to confront you with the grim news:

Intriguingly, the criminals behind this attack don’t supply you with an email address or a website by which to get in touch.

The crooks instruct you to contact them simply by sending the blackmail money to a specific Bitcoin address (in current attacks, they’re demanding BTC 0.03, presently about $1250 [2022-03-23T15:00Z]).

Reply by blockchain

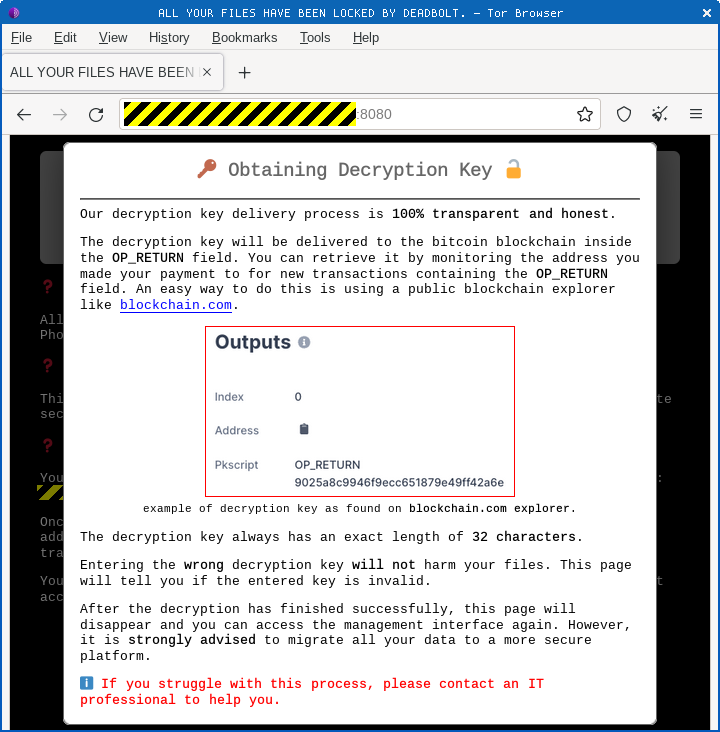

They promise to send you the 16-byte decryption key you need via a return transaction, encoding the data as a transaction message on the public Bitcoin blockchain:

The business of using cryptocurrency blockchains for exchanging messages with cybercriminals is common these days. In the infamous Poly Networks hack, where a crook stole cryptocoins collectively worth about $600,000,000, the company notoriously negotiated with the attacker via messages on the Ethereum blockchain. After sending a rather bizarrely worded series of justifications for the cryptocrime, the attacker suddenly messaged 52454144 5920544f 20524554 55524e20 54484520 46554e44 21, which comes out as READY TO RETURN THE FUND! Poly Networks began referring to him as Mr White Hat; agreed he could keep $500,000 as a curious sort of bug bounty; and ultimately, if amazingly, got the lion’s share of the missing cryptocoins back.

The all-you-can-eat buffet

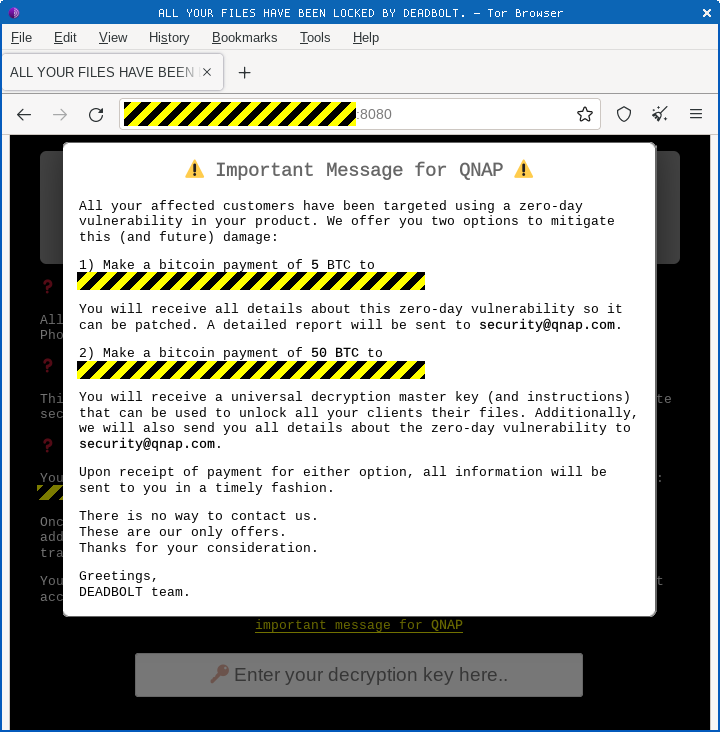

Also, perhaps taking a leaf out of the playbook tried by the Kaseya ransomware criminals, the Deadbolt crew have included what you might call a “meta-blackmail” demands aimed at QNAP, the makers of the device itself.

For BTC 5 (just over $200,000 today), the crooks claim that they’ll reveal the vulnerability to QNAP, although that offer seems redundant in March 2022 given that QNAP’s QSA-21-57 bulletin states that it identified and patched the hole itself back in January this year.

And for BTC 50 (more than $2 million today), the crooks promise to provide a magic “all-you-can-eat buffet” ticket that will decrypt any device infected with the current strain of Deadbolt malware:

The Kaseya gang notoriously demanded $70,000,000 for their “ultimate decryptor”. (Whether that was in the hope that victims might rally together and actually pay up, or simply to thumb their noses at the world, we couldn’t tell at the time.)

Interestingly, with one of the alleged perpetrators of the Kaseya attack now awaiting trial in Texas, we may yet find out more about that $70m blackmail note:

Good news and bad news

The good news in the Deadbolt story is that QNAP not only published a patch for the QSA-21-57 vulnerability back in January 2021, but also apparently went on to take the unusual step of automatically pushing out that update even to devices with automatic updating turned off.

The bad news is that the online internet security scanning service Censys is reporting that Deadbolt infections have suddenly leapt back onto its radar, with more than 1000 affected devices showing up in the past few days.

As it happens, spotting devices affected by this malware is fairly easy.

If a publicly accessible IP number has a listening HTTP server, then the first few lines of HTML sent back in the web server’s main page will give away whether that the server has already been scrambled by Deadbolt (or, alternatively, that it’s deliberately pretending to have been attacked).

As you can see in the screenshots above, the Deadbolt extortion page has a dramatic, all-caps title that is easy to detect using a simple text search at the top the HTML page, which starts like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

[. . .]

<title>ALL YOUR FILES HAVE BEEN LOCKED BY DEADBOLT.</title>

[. . .]

What we can’t tell you is why these infections have returned.

Admittedly, 1000 visibly affected devices is a tiny number against the size of the global internet and the huge number of devices QNAP has sold, so it’s perfectly possible that these numbers have arisen entirely from devices that failed to update back in January and February, despite QNAP’s efforts to update everyone regardless of their auto-update settings.

It’s also possible that the crooks behind Deadbolt have come up with a brand new exploit, or a variation on the exploit they used before, though you might expect a bigger surge in new Deadbolt infections if the crooks really had come up with a fresh attack.

And it’s even possible that some unpatched devices that were theoretically at risk before, but weren’t exposed to the internet, have recently been opened up to attack by users hurriedly “reviewing” and revising their network configurations – and perhaps promising themselves to “make more backups more often” – in the light of current cybersecurity anxieties provoked by the war in Ukraine.

We suspect, however, that the Deadbolt crooks, or someone associated with them, simply decided to have another try, on the grounds that what worked before might very well work again.

Whatever the reason, you’ll be happy to know that no one seems to have paid up, because the Bitcoin address redacted in the screenshots above (we saw just one address, for victims and QNAP alike, in all the recent samples we looked at) currently shows a balance of zero, and an empty transaction history.

A grand cracking challenge

Fascinatingly, the Deadbolt crooks have left a tempting but as-good-as-impossible clue to that 50-bitcoin master decryption key, right in the blackmail page they install on each infected device.

If you enter a decryption key, the web page itself checks to see if it’s valid before activating the decryptor, presumably to prevent you from “decrypting” the data with the wrong key, which we’re guessing would leave you with doubly-encrypted, garbled data rather than stripping off the encryption originally applied.

To prevent you simply reading the decryption key out of the JavaScript source, the web page checks that the decryption key you enter has the SHA-256 hash it expects, rather than directly comparing your input with a text string stored in the code.

And although you can easily go forwards from the correct key to the matching hash, SHA-256 is specifically designed so you can’t go the other way, thus allowing the right password to be verified if you know it already, but not to be recovered if you don’t:

function check_key() {

sha256_hex_bytes($('keyinput').value).then(r => {

if (r === "xxxx[REDACTED]xxxx") { // <--this one is unique to each attack

$('key_info').innerHTML = 'correct key detected...';

$('keysubmit').style.display = 'inline';

$('keysubmit').disabled = false;

} else if (r == "93f21756aeeb5a9547cc62dea8d58581b0da4f23286f14d10559e6f89b078052") {

$('key_info').innerHTML = 'correct master key detected...';

$('keysubmit').style.display = 'inline';

$('keysubmit').disabled = false;

} else {

$('key_info').innerHTML = 'invalid decryption key entered.';

$('keysubmit').style.display = 'none';

$('keysubmit').disabled = true;

}

})

}

As you can see, there’s a test for the one-off key unique to your infected device, but there’s also a test that claims to check whether you’ve put in the multi-million dollar master key offered for sale to QNAP.

So, if you can figure out the input data that would produce a SHA-256 hash of 93f21756 aeeb5a95 47cc62de a8d58581 b0da4f23 286f14d1 0559e6f8 9b078052 …

…you’ve just cracked this particular ransomware for everyone.

What to do?

Here’s our advice for protecting specifically against this malware, as well as protecting generally against network attacks of this sort:

- Don’t open your network servers up to the internet unless you really mean to. QNAP has advice on how to prevent your NAS device from receiving connections from the public internet by mistake, thus preventing your device from being accessed or even discovered in the first place. Perform a similar check for all the devices on your network, just in case you have private devices that can inadvertently be “tickled” from the internet.

- Don’t rely on automatic patching working every time. Whether it’s a NAS device, your mobile phone, a smart TV or a laptop, don’t simply “set and forget” automatic updates. Regularly verify that any updates you do receive, whether they’re forced on you, automatically fetched or manually requested, have gone through correctly.

- Don’t use Universal Plug-and-Play (UPnP). The UPnP “feature” sounds very useful, because it’s designed to allow routers to reconfigure themselves automatically to make network setup of new devices easier. But it comes with enormous risks, namely that your router might inadvertently make some new devices visible through the router, thus opening them up to untrusted users on the internet. QNAP’s advisory shows you how to prevent your NAS device from using UPnP, but we also recommend that you turn off UPnP in your router itself. If you have a router than supports UPnP but won’t let you turn it off, get a new router.

- Don’t rely entirely on online backups. Along with any online backups such those made to connected NAS units, you should also maintain an offline backup that can’t be wiped out automatically in a cyberattack.

When it comes to backups, you might find the “3-2-1 rule” handy.

The 3-2-1 principle suggests having at least three copies of your data, including the master copy); using two different types of backup (so that if one fails, it’s less likely the other will be similarly affected), and keeping one of them offline, and preferably offsite, so you can get at it even if you’re locked out of your home or office.

Remember to encrypt your backups so that stolen backup devices can’t be accessed by the thieves.

If you don’t have the experience or the time to maintain ongoing threat response by yourself, consider partnering with a service like Sophos Managed Threat Response. We help you take care of the activities you’re struggling to keep up with because of all all the other daily demands that IT dumps on your plate.

Not enough time or staff?

Learn more about Sophos Managed Detection and Response:

24/7 threat hunting, detection, and response ▶

Bill D.

Especially well done article.

Paul Ducklin

Thanks. Glad you enjoyed it!

Richard

Ummm… you completely left out the most recent Deadbolt attack against Asustor NAS products that started 4 weeks ago.

Paul Ducklin

I’m not sure the infections you mention are “the most recent attack” if the latest attack is this resurgence reported in the past few days :-)

To be clear, the purpose of this article, given that it’s not so much news as history, is not to identify every possible product that might have been infected and attacked, but to review the MO of Deadbolt, notably the somewhat unusual ways that the ransomware note gets prepared, that the decryption key is messaged back to victims, and that the “master decryption” key is handled.

(As you can see, the tips we published aren’t QNAP or even Deadbolt specific – they’re just lessons you can learn from this sort of incident.)

HtH.

Tony King

QNAP pushed out an update, even to those devices with auto-update turned off???? That suggests there’s some kind of back door in these products. How can a user be confident no bad actors can access that way?

Paul Ducklin

I’m not sure how it ws implemented in the QNAP products. But an “update that will happen anyway” can be done without a backdoor of the sort that I think you are thinking of.

For example, imagine an autoupdater that always runs at least once every day to see what sort of updates are available, if any. The updater could be coded to recognise three types of update: “a regular update is available; install it without asking only if autoupdating mode is selected”; “an important update is available; ask the user about it, even if autoupdates are off, and update if they agree; or “a critical update is available; install it without asking, regardless of the autoupdate setting”.

The updating mechanism almost certainly relies on the device “calling home”, regardless of the type of update to be fetched, just in case the device ends up installed behind a router or firewall that doesn’t allow inbound connections and can’t be reconfigured to do so.

As for how you verify the correctness of updates, whether they are automatic, by request, or forced…

…that’s a related-but-different issue that is usually dealt with through security verification such as sticking to download servers with TLS certificates signed by a specific certification authority, and sticking to downloaded code that’s code-signed by a known certifier, too.

Angelique

Good read, thanks.

PS: Under all you can eat buffet header, last line. Jack instead of Back. You’re welcome.

Paul Ducklin

Thanks. And thanks.

(J is not too far from B on the keyboard, but on the standard QWERTY UK/US layout it’s still a knight’s move away. Interesting typo!)

Peejay

Betcha this is how Russia is now funding its war effort and economy

Paul Ducklin

As mentioned above, the BTC address in this latest round of infected devices has received $0 so far, so fortunately it’s not working…

Anonymous

Yeh, it’s back – just got hit with it 2 days ago.

Also, it looks like many people ARE paying the ransom to get their data back :(.

Nadim Joseph Omran

Since I was infected in the 25th of January. I refused to pay and had to work a lot to get most of my files back from backups or recreate some.

But many many users and small companies have paid because I’m always reading on blogs following these DeadBolt Attacks.